RADIUM AGE: 1921

By:

September 12, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1921.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1921, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: DEEP SPACE.

- Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We (1921). This dystopian novel, set in a totalized social order whose citizens (“ciphers,” with numbers for names) eat, sleep, work, and even make love like clockwork, extrapolates from the rhetoric of those communists who advocated extending Taylorism and other capitalist scientific-management techniques beyond the factory into all spheres of life. Zamyatin’s fable isn’t anti-utopian, but anti-anti-utopian. Like his protagonist, mathematician and rocket designer D-503, the author longed to see war, hunger, and poverty eradicated through collectivism… but not at the cost of spontaneity and freedom of choice. Their ancestors were right to invent a more equitable social order, the female revolutionist I-330 tells D-503. But afterward, she adds (speaking in a mathematics-inflected register intended to subvert D-503’s lifelong conditioning) “they believed that they were the final number — which doesn’t exist in the natural world, it just doesn’t.” Fun fact: We circulated in samizdat for years — in which form it influenced George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.

- Frigyes Karinthy’s Capillaria (1921). Gulliver, protagonist of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, who in Karinthy’s 1916 Voyage to Faremido: Gulliver’s Fifth Voyage (1916) visited a planet of intelligent machines, now finds himself saved from drowning in an underwater empire ruled by women. The males (“bullpops”) of this planet are fighters and builders, creative and rational… yet they are dominated by the emotional, illogical womenfolk. Not only do the women of Capillaria devote themselves entirely to pleasure, and tear down the (phallic) towers erected by the men, but they feed on the brains of their menfolk! A misogynistic adventure influenced by August Strindberg, who often made pronouncements like, “Woman, being small and foolish and therefore evil… should be suppressed, like barbarians and thieves.” Fun fact: Karinthy’s fifth and sixth journeys of Gulliver’s aren’t the earliest example of Gulliveriana — but they’re among the most influential.

- George Bernard Shaw’s Back to Methuselah: A Metabiological Pentateuch (1921). Shortly after WWI, the secret of Creative Evolution — in Shaw’s formulation, the process by which an organism can will its own entelechy, or self-potentiation — is discovered. By the year 3100 the long-lived elite have developed perfect physiques and advanced mentalities. Zozim and Zoo are Boomer-like superhumans (he’s nearly 100, she’s 50, but they act like young adults) who assist a sham oracle in overawing the short-livers seeking its advice. It’s all part of a plot to colonize and supersede ordinary humans! But like the proto-Yippies they are, Z and Z are upfront about the put-on. Zoo: “[Zozim] has to dress-up in a Druid’s robe, and put on a wig and a long false beard, to impress you silly people…. I have no patience with such mummery; but you expect it from us; so I suppose it must be kept up.” It’s Wild in the Streets meets Highlander. Fun fact: RFK was quoting this Radium Age sci-fi play when he said, “‘You see things; and you say, “Why?” But I dream things that never were; and I say, “Why not?”.’”

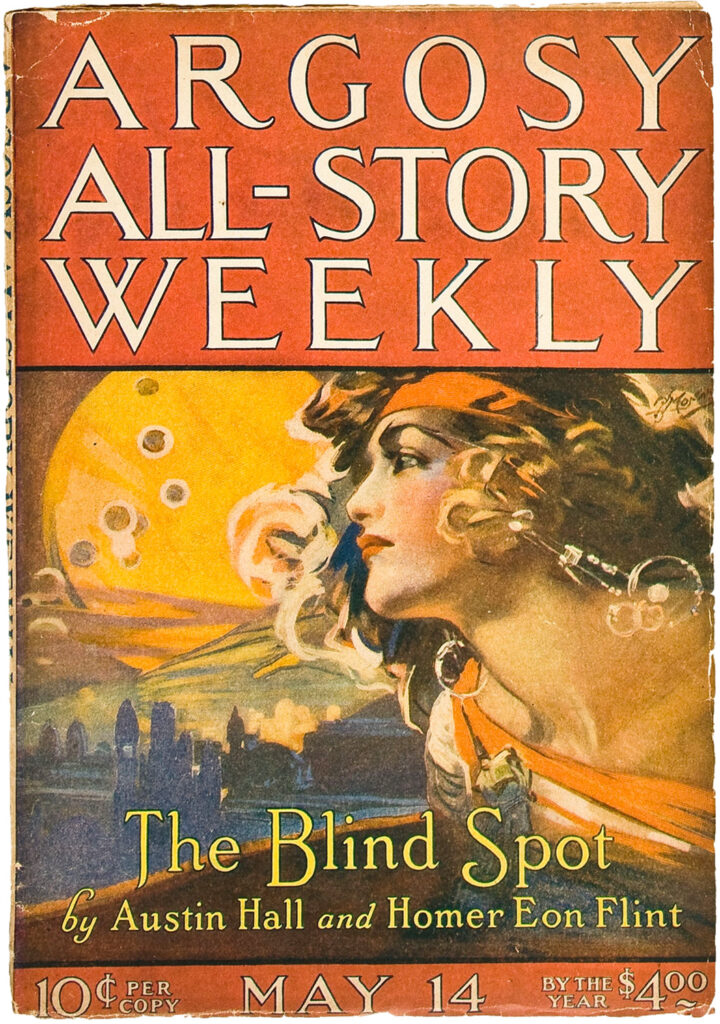

- Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist (1921). Having learned how to visit other worlds telepathically, Dr. Kinney and his companions enter the minds and share the sensations of the inhabitants of Hafen [Heaven], a planet inhabited by capitalists, and Holl [Hell], its twin planet, which is inhabited by workers. (Call it: psi-fi.) Not content merely to study the goings-on, Kinney & co. help the workers’ revolutionary party stop the Hafenites from invading a third planet Alma, which is inhabited by “‘cooperative democrats’; that is, they do not compete with each other for a living, but work together in all things, in complete equality.” Unfortunately, a Hafenite WMD separates the twin planets. This is the third occult-science-fiction Dr. Kinney story; the others are “The Lord of Death” (June 1919), “The Queen of Life” (August 1919), and “The Emancipatrix” (September 1921). Fun facts: Originally serialized in Argosy All-Story Weekly (July 1921); also serialized here at HILOBROW by HiLoBooks. In 1965, Ace published The Devolutionist and The Emancipatrix together; could The Devolutionist and The Emancipatrix possibly be the best sci-fi title ever?

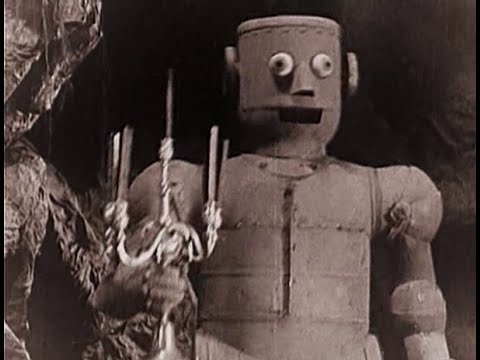

- The Mechanical Man (Italian: L’uomo meccanico) is a 1921 Italian science fiction film directed by André Deed. It is one of the first science fiction films produced in Italy, and the first film showing a battle between two robots. The cinematographer was Alberto Chentrens. The story begins with a scientist creating a device shaped like a man that can be remote-controlled by a machine. The mechanical man possesses super-human speed and strength. The scientist is killed however by a gang of criminals, led by a woman named Mado, who wish to obtain his secret of building a mechanical man. The criminals are captured before they are able to get them, and are brought to trial and condemned. Mado manages to escape and kidnaps the scientist’s niece, forcing her to give her the blueprints which she uses to build a mechanical man.

- Leland S Copeland collected his astronomy-themed verses in Whimsical Rimes, Made by Leland S. Copeland (coll 1921), subsequently appearing in Hugo Gernsback’s magazines.

- Maurice Renard’s L’Homme truqué was no doubt partly inspired by Wells’s “The Remarkable Case of Davidson’s Eyes” (1895) and Rosny aîné’s “Un Autre monde”(1895). But Renard’s protagonist is a WWI French soldier, Jean Lebris, fighting near Strasbourg who, after being blinded by an exploding cannon shell and captured by the enemy, is taken to a top German scientist, Dr. Prosope, who is conducting advanced ophthalmological research. Lebris is fitted with experimental electroscopic eyes which allow him to perceive things far beyond the normal spectrum of human vision. In addition to its strange effects of synesthesia (“seeing” sounds, smells, etc.), his artificial eyes now enable him to see electricity, magnetic fields, the movement of the wind, and all forms of radiation, among other things. Unfortunately for Lebris, these new powers ultimately prove to be a curse because he is unable to block out such visions. And, after continually observing what appear to be invisible, electric beings who coexist—unknown to humanity — on the same plane with us, he eventually falls into a coma and dies.

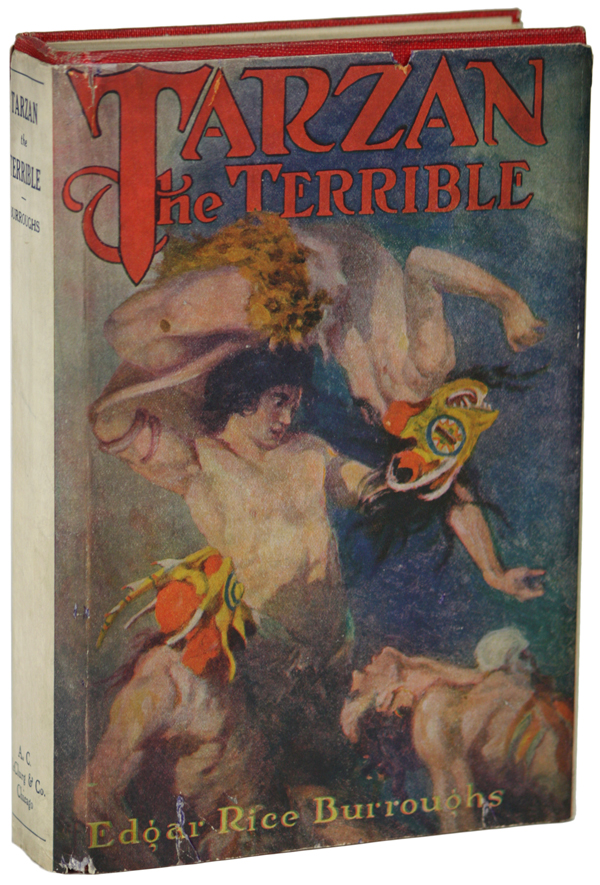

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan the Terrible. Seeking Jane, Tarzan enters the land of Pal-ul-don, inhabited by black and white races, both with tails, and prehistoric beasts. Moskowitz calls it probably the best Tarzan story.

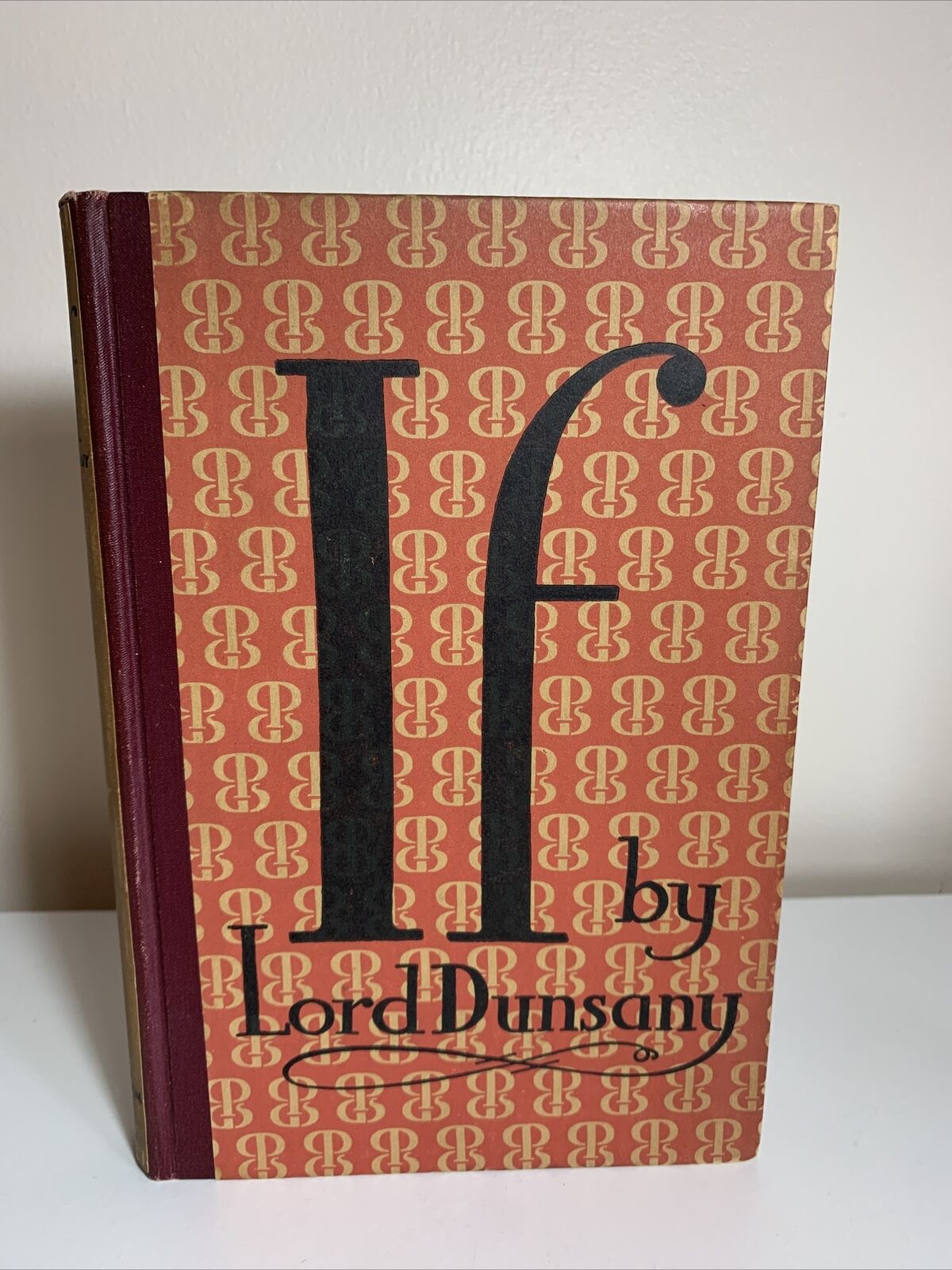

- Lord Dunsany’s If: A Play in Four Acts. Lovecraft: “Truly, Dunsany has influenced me more than anyone else except Poe—his rich language, his cosmic point of view, his remote dream-world, & his exquisite sense of the fantastic, all appeal to me more than anything else in modern literature. My first encounter with him—in the autumn of 1919—gave an immense impetus to my writing; perhaps the greatest it has ever had…” (to Clark Ashton Smith, 30 July 1923)

- Murray Leinster Red Dust sequel to The Mad Planet — Moskowitz says it is “magnificent”

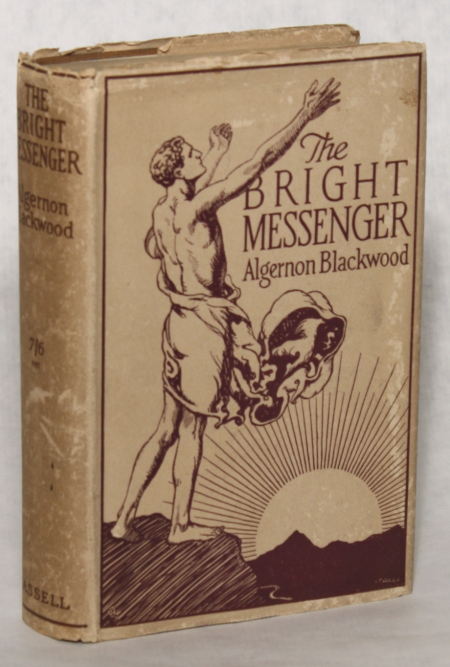

- Algernon Blackwood’s occult adventure The Bright Messenger. Julian LeVallon, born and raised alone in the Western Alps, is referred to psychiatrist Dr. Fillery for care in London. He appears to be a schizophrenic with a secondary personality, “N.H.” (non-human); but perhaps Julian is really an Elemental Being, a “bright messenger” who portends a new age of human evolution! It is Fillery’s hope that he can release N.H., in order to heal the Earth after the War. N.H., however, doesn’t believe that mankind is ready for this next stage in spiritual evolution. Fun fact: Blackwood was fascinated by the notion that Nature spirits had evolved alongside humankind; he wanted to portray a being who was half-human, half-elemental. Henry Miller called this “the most extraordinary novel on psychoanalysis, one that dwarfs the subject.” See 1916 for the novel to which this one is a sequel.

- Austin Hall and Homer Eon Flint’s The Blind Spot. Ashley says Hall’s vivid imagination overcame his bad writing. Moskowitz calls it a mix of very good and very poor writing

- J.U. Giesy’s Jason, Son of Jason. Serialized in six parts in Argosy All-Story (April 16, 1921 – May 21, 1921). This was an early story influenced by Burroughs’s John Carter novels. The main character uses astral projection (explained in detail) to travel to the planet Palos where he occupies the body of a man who has died and then establishes himself as a major figure on the world by bringing modern technology to the primitive society, and wins a princess in the process. Reprinted in a heavily edited version in hardcover by Avalon in the 1960s.

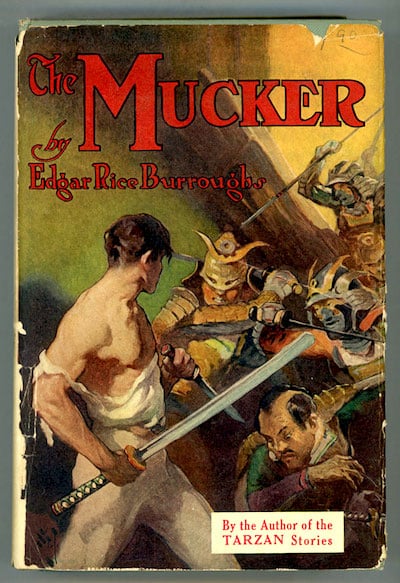

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Mucker. Framed for murder, a young thief and mugger flees to San Francisco, where he is shanghaied. Forced to labor on a vessel headed to the Far East, Billy’s attitude and behavior begins to change for the better. When the ship founders, he helps land it — and rescues Barbara, a kidnapped heiress from pirates. She is then snatched by Malaysian headhunters, so Billy rescues her again… and then protects her in the jungle, where she teaches him how to speak properly. There is a lost-race sequence here, nudging this into proto-sf. (There’s a Tarzan/Jane dynamic at work.) Billy then sets out to rescue Barbara’s father and fiancé — and nearly dies in doing so. He eventually returns to America, where Barbara seeks him out… but he won’t marry her! At least, not until he proves himself innocent of murder. Fun fact: First published in All-Story Weekly in October and November 1914. In his 1965 book Master of Adventure: The Worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Richard A. Lupoff calls this novel “a most remarkable technical achievement,” because it is “virtually a catalog of the pulps.”

- Bruno Hans Bürgel’s “The Cosmic Cloud” (German story published c. 1921; serialized, in English translation, Fall 1931).

- Christopher Blayre (Edward Heron-Allen)’s “Aalila.” In The Purple Sapphire and Other Posthumous Papers. An astronomer falls in love with a Venusian girl via photo-telephone. It has been pointed out that this story has a similar plot to a later work of sf horror, William Sloane’s To Walk the Night.

- Christopher Blayre (Edward Heron-Allen)’s “The Cosmic Dust.” In which it is suggested that life originated from radium.

- Coutts Brisbane’s “The Little Bit of Fat” — Wellsian dying earth story.

- Stanislav Vinaver’s surrealist story collection Gromobran svemira (Lightning Rod of the Universe). The title story and the story “Osveta” (“Revenge”) feature sf elements. He is considered one of the key representatives of the Serbian and Yugoslav literary avant-garde.

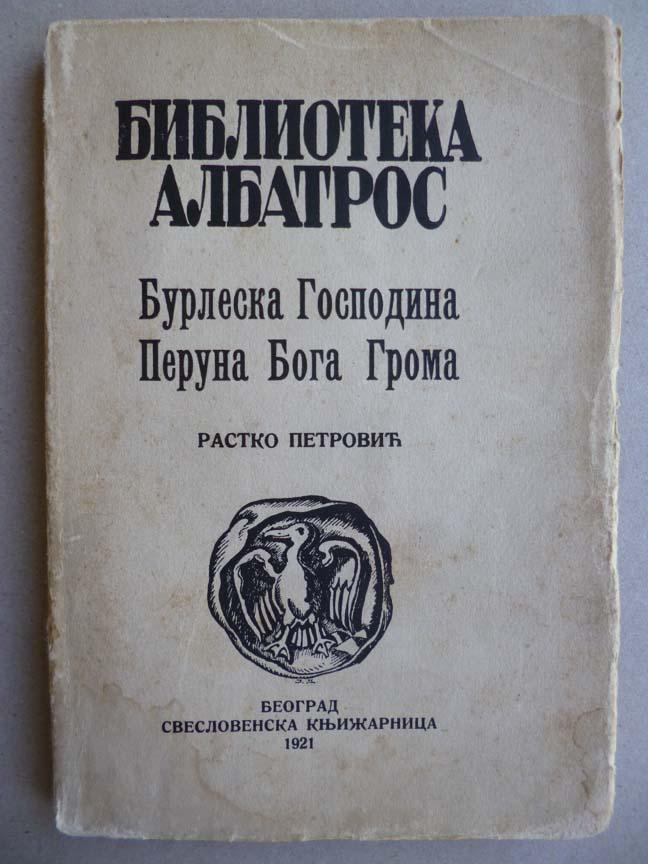

- Rastko Petrović’s Burleska gospodina Peruna boga groma (The Burlesque of Mr. Perun, God of Thunder), another surrealist novel with sf elements.

- George R. Wells’s “The Transformation of Professor Schmitz.” Ashley says it gives an original twist to matter-transmission stories – in Science and Invention magazine.

- Joan Conquest’s Leonie of the Jungle. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Georges Lebas’s Jean Arog, le premier surhomme. Paranoid account of a superman threatening humankind. Arlog has managed, by dint of work on his mind and an immense will, to “aggregate the atoms of souls scattered in each thing and force them to move.” Godlike in his abilities, he will take as his motto: “Whatsoever I want.” He blocks a locomotive by sheer force of thought, etc. But a frightened and superstition populace turns on him — leading him to contemplating stopping the Earth in its tracks long enough to wipe everyone out. The reader is left to wonder whether Arlog really possessed these powers or not… the only witness to his deeds is unreliable.

- J.D. Beresford’s story collection Signs and Wonders. “Signs and Wonders” is about “the idea of the imperceptible transition from this ultimately dispersing matter to thought or impulse—from the various bodies, etheric, astral, mental, causal, or Buddhistic, to the free and absolute Soul.” Bit it’s all a dream…. “The Perfect Smile” reminds us of the author’s Hampdenshire Wonder; a wicked child’s smile is described as “so radiant, so tender, forgiving, and altogether godlike.” The story “A Negligble Experiment” is a reverie in which the Earth is destroyed by a new planet: “This experiment of making men upon the Earth is now proved to be negligible,” a character says. “In a few hours it will be finished, wiped out. And whether that termination is the result of accident or design makes no difference to the effect. This is an answer to all our philosophies and religions. Either we are the creatures of some chance evolutionary process, or we are an experiment that has failed.”

- J.D. Beresford’s Revolution: A Story of the Near Future in England. A determinedly objective analysis of a near-future socialist revolution in the UK.

- Marie Corelli (Mary Mackay)’s The Secret Power: A Romance of the Time. Features an advanced airship (in which the heroine discovers a super-scientific lost race in the Sahara Desert) and atomic bombs, intended to put an end to war — whose inventor inadvertently detonates them, triggering a great earthquake in California, with a focus on Los Angeles. The SFE says of Corelli: “By the early 1900s her odd brand of sublimated sex, heated religiosity, self-absorbed ‘female frailty’ and unctuous fantasy had begun to lose its appeal, and her sales were further diminished after her conviction for food hoarding in 1917; by her death she had been virtually forgotten.”

- Bruno Bürgel’s Der “Stern von Afrika.” A tale of the future set in the year 3000 A.D. after Earth has entered a new ice age following its passing into a cloud of cosmic dust. Most of Earth is either uninhabitable or barely habitable and the center of civilization is in Africa. Technology is advanced but not enough to avert the probable extinction of all life on the planet. Published in English as “The Cosmic Cloud” in Wonder Stories Quarterly, Fall 1931.

- H. Rider Haggard’s She and Allan. Haggard, the king of sequels, here writes what is almost a piece of fan fiction, one which unites characters from two hugely popular earlier novels of his. Hoping to communicate with deceased loved ones, the English-born professional big game hunter Allan Quatermain (from Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines, 1885) seeks out a great white sorceress who rules a hidden African kingdom. On the way there, Quatermain meets a fearsome Zulu warrior chieftain, Umslopogaas — who, by the way, will become a recurring character in future Haggard adventures. Quatermain and Umslopogaas seek to rescue a beautiful European girl from a tribe of cannibals, and the chase takes them to the ruins of the ancient city of Kôr… where dwells Ayesha, the immortal enchantress (from Haggard’s She, 1886). Ayesha enlists Quatermain and Umslopogaas to lead her warriors against the forces of Rezu, a fearsome upstart. Oh, and Allan communes with the dead! Fun fact: She and Allan is an early example of a prequel; it takes place before the events of King Solomon’s Mines and She. The character Ayesha was a hugely influential one: C.S. Lewis patterned the White Witch on Ayesha; and Tolkien’s Galadriel is a version of She, as well.

- Juliette Bruno-Ruby’s Celui qui supprima la mort — is it sf?

- Otto Soyka’s Die Traumpeitsche (The Dream Whip). A novel about a chemical substance that influences people’s dreams. Note that the Soyka (an Austrian) wrote novels in which human beings are manipulated by mysterious psychic powers; also see Der Seelenschmied (The Soul Smith). Thus we are led to see the institution, at the level of popular culture, of a fantastic mythology that would eventually find its reification in the ideology of National Socialism.

- Robert Müller’s Camera Obscura. A many-leveled futuristic mystery novel by an expressionist author. A superman of Nietzschean dimensions without moral limitations would rather destroy the world than accept the failure of his ambitions.

- Stephen Vincent Benét’s “The Tinsel Heaven – a Dream.” Involves space flight.

- Valery Bryusov’s Diktator (The Dictator). One of the most interesting antiutopias by Bryusov is this tragedy in five acts. The author returns in it to a vision from his childhood about the possible settlement of Venus. People have finished their expedition to Venus and have brought back with them some inhabitants of that planet, who resemble gorillas. They keep them in cages like animals and plan to send most of the population of the overcrowded Earth to Venus. This populist intention is part of the pre-election campaign of the Central Council Chairman Orm, who later becomes a dictator. But his dictatorship over the globe does not last long. People, tired of many years of expensive preparations for the interplanet expedition, rise up in rebellion. The revolution is gradually joined by more and more continents. The Dictator is saved in the end by a bullet from his sympathetic mistress. (Written after the first experience of the October Revolution and the early years of the dictatorship.)

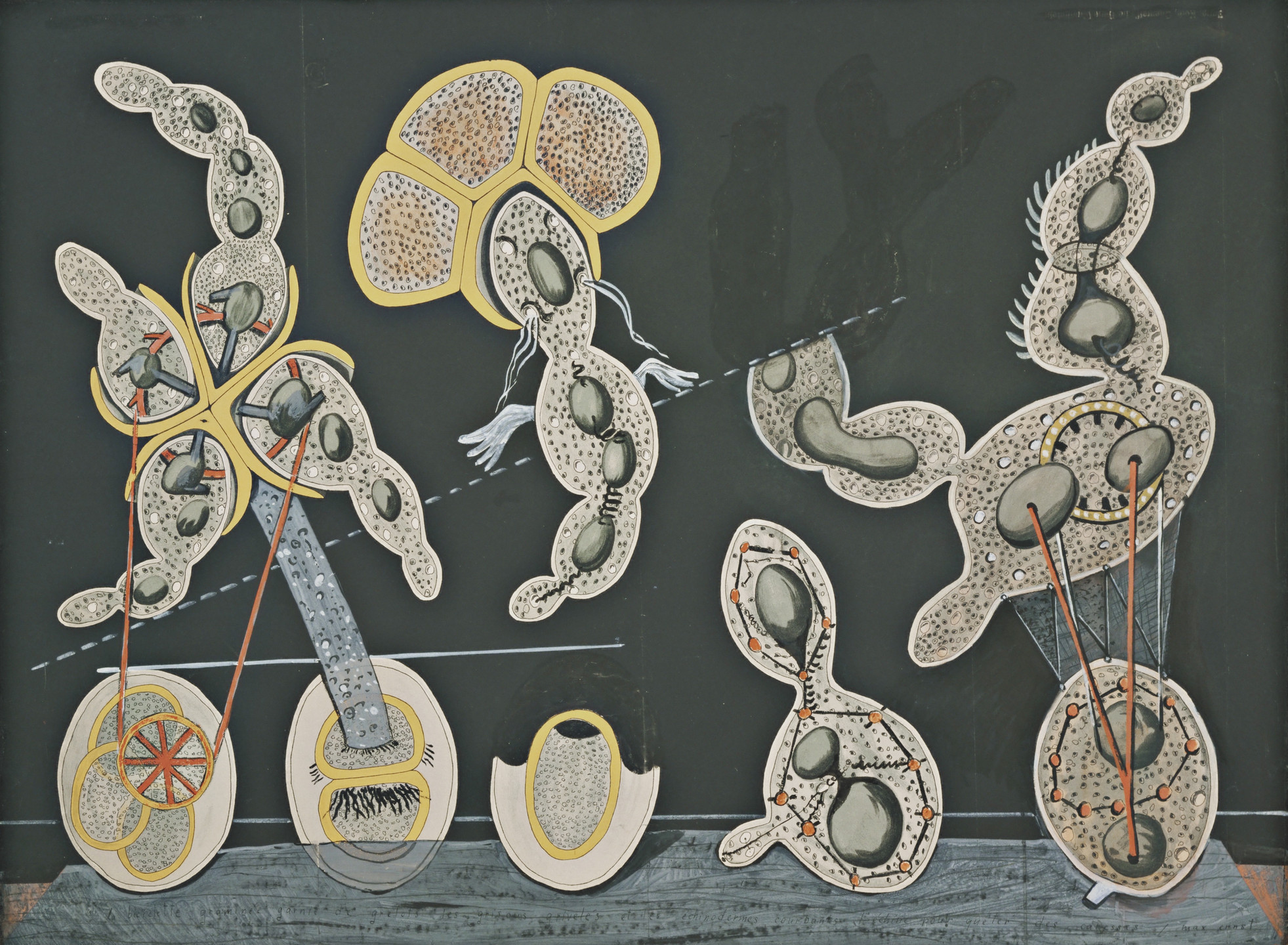

The central rotund shape in this painting derives from a photograph of a Sudanese corn-bin, which Ernst has transformed into a sinister mechanical monster. Ernst often re-used found images, and either added or removed elements in order to create new realities, all the more disturbing for being drawn from the known world. The work’s title comes from a childish German rhyme that begins: ‘The elephant from Celebes has sticky, yellow bottom grease’. The painting’s inexplicable combinations, such as the headless female figure and the elephant-like creature, suggest images from a dream and the Freudian technique of free association.

ALSO: While working with Bohr, Rutherford theorizes about the existence of neutrons; his theory would be proven in 1932. Rutherford and Chadwick disintegrate almost all the elements as a preliminary to splitting the atom. Isotopes isolated, chromosome theory of heredity proposed, medium voltage x-ray therapy advocated. John Maynard Keynes publishes A Treatise on Probability. Soddy wins the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, Einstein for Physics. Oberth, one of the founders of modern aeronautics, writes his dissertation The Rocket into Interplanetary Space. Russell’s The Analysis of Mind, Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. A 14-year-old farm boy. Philo Farnsworth, devises the image dissector, the basis for the first version of television. Paris conference of Allies fixes German reparation payments; Hitler’s storm troopers (SA) begin to terrorize political opponents; Germany’s economy begins to collapse. Harding becomes US president, Faisal I becomes king of Iraq. Sacco and Vanzetti found guilty of murder. KKK activities become violent throughout southern US. Dos Passos’s Three Soldiers, Lawrence’s Women in Love, Pound’s Poems 1918–1921, Sabatini’s Scaramouche. Braque’s Still Life with Guitar, Ernst’s The Elephant Celebes, Kokoschka’s Music, Picasso’s Three Musicians. Andre Breton, a founding member of the Paris Dada circle, stages a mock trial of a libertarian author who’d become an ultranationalist during the war; this precipitates a break between Breton and Dada cofounder Tristan Tzara, who rejects the idea of one person holding moral authority over another. Chaplin’s The Kid.

Einstein’s 1921 address “Geometry and Experience” argues that geometry is a natural science — in fact, “the most ancient branch of physics.” He then goes on to consider the geometry of the universe – a startling notion. He ends this talk with a description of the correspondence between the sphere and the “flat sphere” (see Rucker) via stereographic projection, and the way in which one can thus visualize a hypersphere by imagining our space to be a ‘flat hypersphere.'”

Ouspensky comes to England in 1921, determined to set up an organization of his own — with the help of A. R. Orage, editor of The New Age. A large house in London became the headquarters of Ouspensky’s Historico-Philosophical Society — which aims to pursue methods of self-study related to “psycho-transformism” and the possibilities of development of mankind. His lectures will be attended by Aldous Huxley, T. S. Eliot, and others; he was a key influence on the UK literary scene of the 1920s and 1930s.

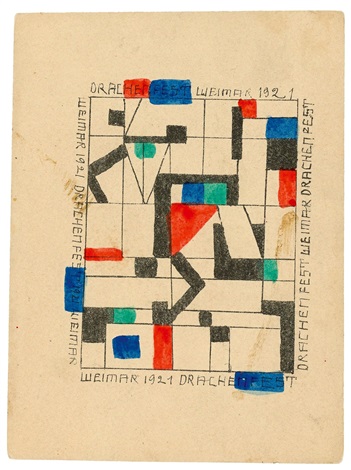

Schjeldal: “In 1921, Kandinsky moved with Nina to Berlin, where the art world embraced him. He soon became a prominent teacher at the Bauhaus, in Weimar and, later, Dessau; in 1928 he took German citizenship. He could luxuriate in social and professional contacts with leading lights—including membership in an exhibiting group, the Blue Four, with Paul Klee, Feininger, and Jawlensky—but his style calcified into tricky panoplies of stock modernistic forms, more suited to punchy graphic art than to the fascinations of painting. Though Kandinsky’s inventiveness never flagged, as a sideshow at the Guggenheim of his unquenchably lively drawings confirms, his sense of “inner necessity” (a key term in his theory of art) wandered. With busy, compulsively tidy compositions, in increasingly sugary colors, he became his own leading imitator.”

Yeats’s “Second Coming” (1921).

From The Present Age After 1920:

Meanwhile, [Yeats] was searching for a mystical philosophy which could impose some order on experience and take the place of the orthodox religion which for hum had been destroyed by Huxley and Tyndall. [This is in reference to something Yeats said about his frustrated religiosity.] The story of Yeats’s adventures among theosophists, mystics, spiritualists, hypnotists and other eccentric thinkers is strange enough, the surprising thing is that Yeats drew nourishment from them all, and the magical system which he eventually constructed for himself and described in his book, A Vision — it combined a system of magic, a philosophy of history and a philosophy of personality — was able to provide the central core of order in such great poems as “The Second Coming” and “Byzantium.”

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin