RADIUM AGE: 1919

By:

August 28, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

According to my eccentric periodization scheme, the years 1918–1919 are the apex of the cultural decade known as the Teens (1914–1923).

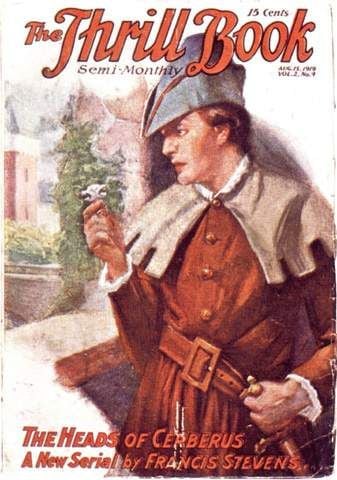

The Thrill Book (Street & Smith) started in dime novel format — competition to All-Story Weekly and The Argosy for fantastic material — in March 1919 before converting to pulp format after four months. It was a magazine for stories that were unusual or unclassifiable in some way, which in most cases meant that they included either fantasy or proto-sf elements. It ceased publication in October 1919, having lasted sixteen issues; it carried some proto-sf, particularly towards the end of its short run, but is not generally regarded as an sf or fantasy pulp.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1919.

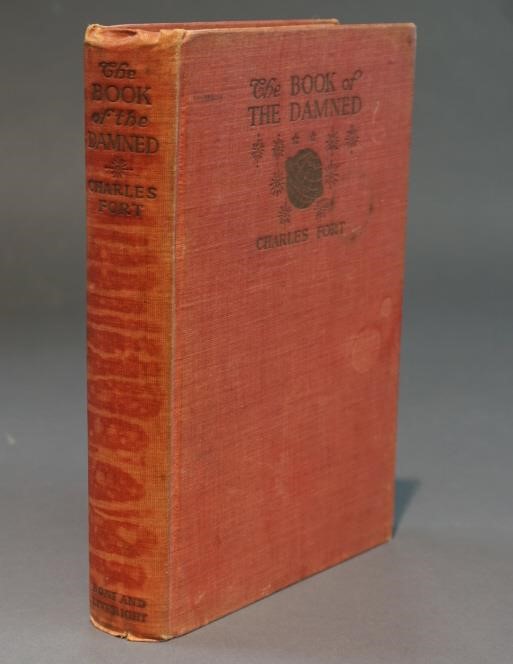

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1919, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: ALIEN (of or pertaining to an (intelligent) being or beings from another planet; that derives from another world — in A. Merritt’s Moon Pool) | “DIFFERENT” STORY (esp. in the early pulp era: a science fiction, fantasy, or weird story; an impossible story — G. Hovey Letter in All-Story Weekly: “Why can’t we have a ‘different’ story every week? They are great.”) | FANBOY | SUPERSCIENTIFIC (of or pertaining to superscience n.; relating to or generated by the products of super-science — in C. Fort’s The Book of the Damned).

- Rose Macaulay’s What Not: A Prophetic Comedy (1919). At some point after the Great War [that is to say, after the First World War, which ended a few months after Macaulay wrote this book], in a Britain where people travel by underground train and “street aero,” a government ministry — the Ministry of Brains — decides to increase national brain-power, and stave off the coming idiocracy, through a program of compulsory selective breeding. The propaganda efforts in support of this endeavor are amazing, and wide-reaching… not just official posters, but newspaper editorials, business advertisements, contests, and more. However, when it’s discovered that the head of the Ministry has secretly married, even though — because there is “deficiency” in his family — he is not allowed to do so, the Ministry is burned down. The book ends on an ambiguous note: Is the victory of “human perverseness, human stupidity, human self-will” over autocratic bureaucracy a triumph? Or not? Fun fact: When British censors discovered that What Not ridiculed wartime bureaucracy, its planned 1918 publication was stopped. Macaulay is best known, today, for her award-winning final novel, The Towers of Trebizond (1956). Reissued by MIT Press’s Radium Age series, with a new introduction by Matthew De Abaitua, in 2022.

- Francis Stevens’s The Heads of Cerberus (serialized in Thrill Book, 1919; as a book, 1952). In this pre-PKD epistemological thriller, three Philadelphians accidentally inhale dust from an ancient vial whose cap is shaped like the mythological three-headed dog Cerberus. It turns out that the dust was invented by a scientist who has discovered parallel universes. They are transported into a strange land populated by supernatural beings, then whisked back to Philadelphia… which has changed. It is the year 2118, and Philadelphia has become a dystopian nation-state ruled by the “Penn Service.” Ordinary citizens are numbered, not named; the Liberty Bell has become an object of veneration it is is believed that the land will dissolve if it is ever rung. The post-1918 history of this world has been shaped by the inventor of the dust, Norman Power, who seems (like a character from Philip K. Dick) to inhabit all the worlds to which he gives potential life. Is this Philadelphia real? Are they somehow creating it? What is reality? Ashley calls it the most important sf story published in The Thrill Book, historically important as one of the first stories to suggest the possibility of alternative time tracks. Moskowitz mentions in Scientific Romance as the high point of The Thrill Book‘s fantasy-fiction content.” Fun fact: Gertrude Barrows Bennett (1883–1948), who published under the pseudonym Francis Stevens, was a pioneering American female writer of fantasy and science fiction.

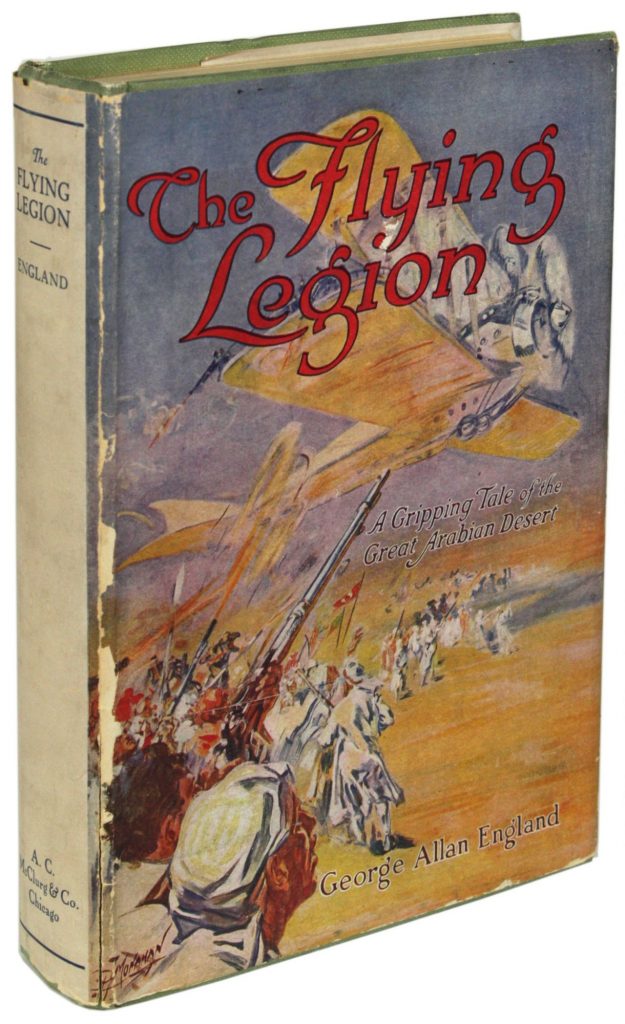

- George Allen England’s The Flying Legion (15 November-20 December 1919 All-Story Weekly; 1920) is a heist story of the near future. A wealthy soldier of fortune and Islamist, whose inventions far surpass world technology of his day, forms the Legion in an unsuccessful attempt to reform Islam, which he believes to be the true religion. Involves the theft from Mecca of Islam’s most sacred relic, a giant aircraft, restless adventurers, supermen and superwomen. Very pulpy indeed. Shown above is the 1920 book version.

- G.K. Chesterton’s “England in 1919” is told as though written in 1969. A satire in which Chesterton reconstructs a history of the year 1919, looking back from a future after which a 1943 “Futurist Government” had destroyed virtually all records of the past, and from which all scientific machinery had been banned by an earlier “Simple Life Government” of 1929. Chesterton takes aim at plutocracy and the purchases of peerages. There are amusing misinterpretations of history, e.g., the author’s identification of King George with Lloyd George and Lloyd’s the shipping insurers; also his conclusion that Napoleon met his Waterloo on the playing fields of Eton rather than among the rusted iron tracks of Waterloo, a railway station in South London. Fun fact: The story appeared in an all-(proto)-sf Christmas issue of the English journal Pears’ Annual; some British sf scholars half-seriously argue that this issue deserves to be recognized as the world’s first sf magazine.

- Efim Zozulya’s “The Dictator: The Story of Ak and Humanity.” A darkly humorous parody of Bolshevik utopian eugenics, in which the Council of Public Welfare running the city of Ak issues a decree that they have decided to liquidate all “superfluous” persons. “Those who lack the courage to terminate their existence, if ordered to do so by the COUNCIL OF PUBLIC WELFARE, will be aided by the COUNCIL,” a poster announces. “The sentences will be carried out by the friends and neighbors of the condemned, or by a special military detachment.” The thinly veiled critique of the Soviet regime, written merely a year and a half after the Bolsheviks gained power in Russia, helped establish the anti-utopia genre, and directly inspired and influenced Zamyatin’s We, which was finished a year later. Translated by Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman’s boyfriend who was deported to the Soviet Union with her during the Red Scare post-World War I. Collected in 1917: Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution, edited by Boris Dralyuk. For more info, see Drozdz’s essay on “Parodies of Authority in the Soviet Anti-Utopias from 1918-1930.” Fun facts: “Yefim Zozulya may be the greatest Russian fabulist you’ve never heard of,” claims Tor.com. This story is one of his two masterpieces, the other being “The Doom of Principal City” (1918). Read it here.

- Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie’s A Romance of Two Centuries. Takes place in 2025, which is coming right up. A utopian story with a very detailed blueprint of the future. “The narrative portion is subordinate to revelation of things to come… many of the details of Guthrie’s predictions are surprisingly apt.” – Bleiler.

- A. Merritt’s “Three Lines of Old French.” A story of the borderland between life and death — as told to Merritt, supposedly as the Science Club, by a famous American surgeon. A classic example of proto-sf emerging from occult fiction.

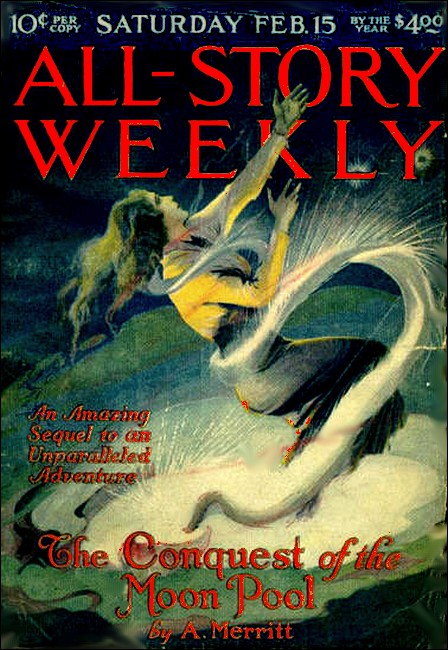

- A. Merritt’s “Conquest of the Moon Pool,” a sequel to “The Moon Pool” (see 1918), appeared in All-Story. It was tremendously popular at the time and also when reissued in 1930. Moskowitz claims that the announcement of this six-part novel was one of the milestones in the history of scientific romance and one of the greatest chapter’s in All Story Weekly‘s history. The book version was a massive bestseller. Confusingly, both stories were later reworked into the novel The Moon Pool in 1919.

- Stefan Grabiński’s Demon ruchu (coll. 1919; trans. Miroslaw Lipinski as The Motion Demon, 2005). SFE entry: “The stories from The Motion Demon are remarkable for their explicit use of trains as engines of release, allowing escape from the immurements of provincial life in Poland: escape and motion being virtual synonyms in Grabiński’s work. Moreover, the dynamics of locomotion, so widely employed and vigorously depicted throughout the collection, could also be defined as a metaphor of the everlasting flow that the stream of life undergoes, or vital energy with no cognizable origin and purpose, which under conducive circumstances manifests itself and takes over, the concept partly drawn from the philosophy of Henri Bergson. The first sentence of “In the Compartment” — “The train shot through the open country at the speed of thought” — ideally defines the zestful nature of his prose, while the whole story portrays a typical Grabinski protagonist who becomes supernaturally potent once aboard a moving train (this being a Futurist topos that surprisingly seems to have had little influence on sf, either American or European), and intoxicates a young married woman into a fatal orgy.”

- Aage Heinberg’s Himmelstormerne (Danish novel translated into English as Young Titans). Satire and social criticism.

- Austin Hall’s Into the Infinite. Ashley says that Hall’s vivid imagination helped to overcome his lousy writing. This one, though, seems pretty racist.

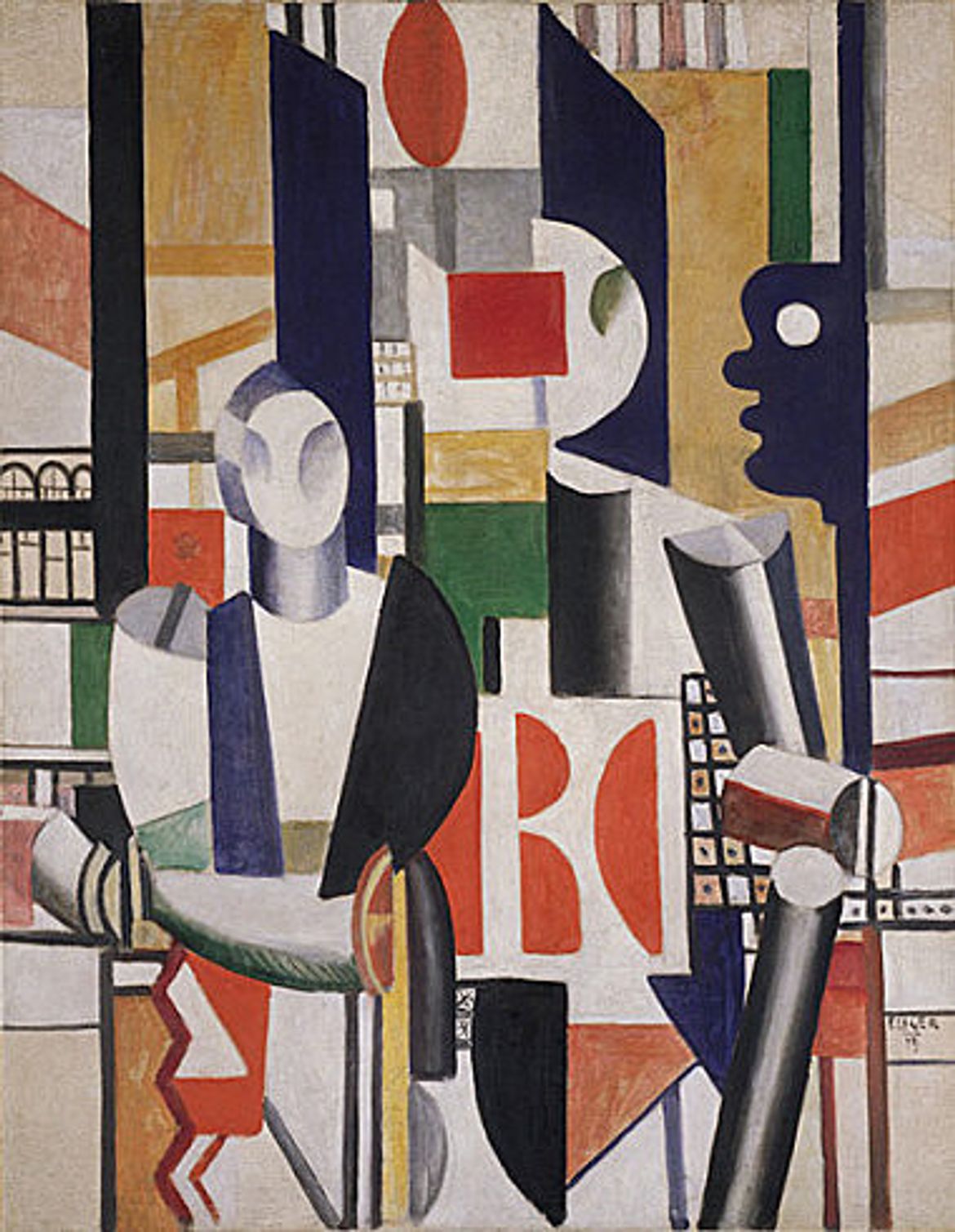

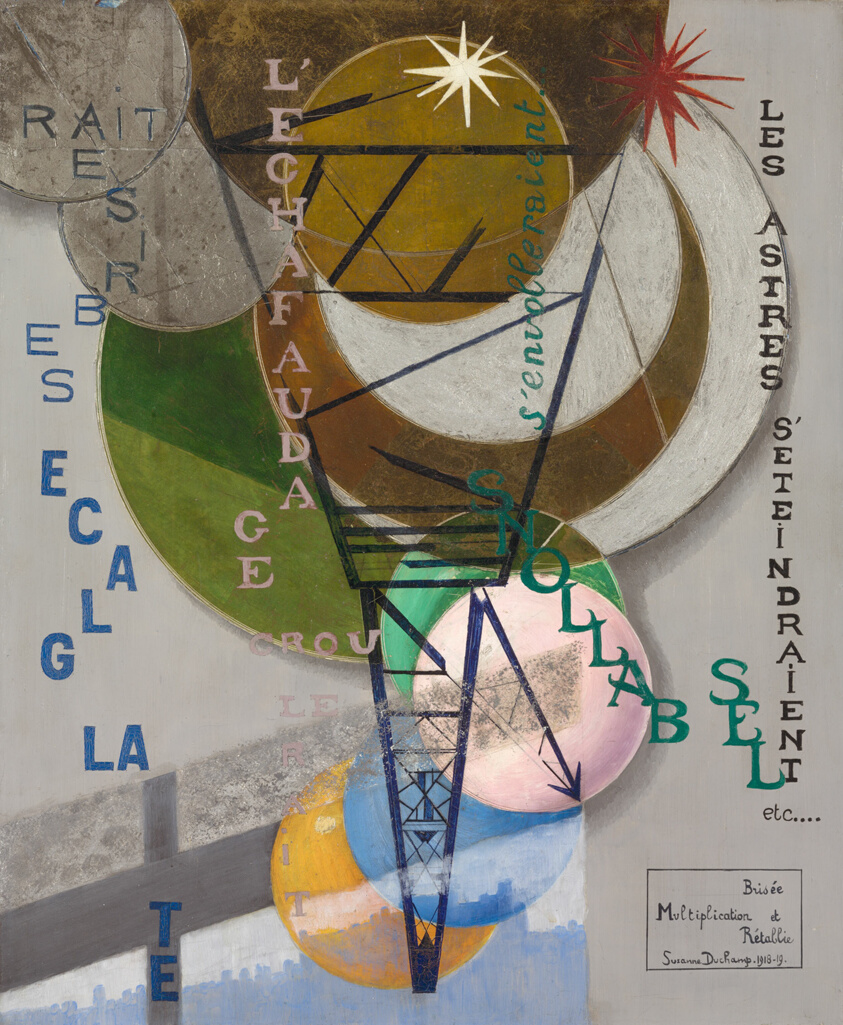

- Blaise Cendrars’ Le fin du monde filmée par l’Ange Notre-Dame (translated by Esther Allen as “The End of the World Filmed by the Angel of Notre Dame”). A script for an imaginary film in which God, having filmed World War One, which satiates him only briefly, now plans to create the End of the World through special effects. A version first appeared October 1916 in La Caravane as “La fin du monde.” Illustrated by the proto-Pop artist Fernand Léger; see above.

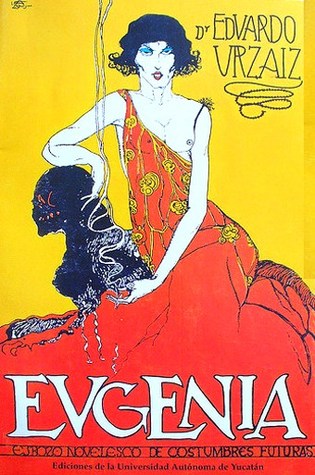

- Eduardo Urzaiz’s Eugenia. A Mexican proto-sf novel. The University of Wisconsin did a scholarly edition in 2016. The first important Mexican proto-sf novel, Eugenia is a scientific and collectivist utopia set in 2218, in Villautopia, capital of the subconfederation of Central America. The state rules with absolute control over the governed. Sexual and monogamist family taboos have been erased and equality among men and women has been achieved. The state also appoints the Official Reproducers of the Species and science has achieved the pregnancy of both male and female. Fun fact: The author was a psychiatrist and university professor.

- Francis Stevens (Gertrude Barrows Bennett)’s “Unseen — Unfeared.” A man’s sanity is threatened when a sinister scientist uses a new form of radiation to reveal the invisible monstrosities always around us. I like how it mashes up fantasy, sf, horror, the detective story; Stevens can do it all.

- Francis Stevens (Gertrude Barrows Bennett)’s “The Elf-Trap.” A university professor, taking a country holiday to soothe his nerves, finds himself drawn into the magical world of the elves. Kind of a fantasy love story — though the main character is a scientist.

- G. McLeod Winsor’s Station X. A proto-sf thriller in which a psychic invasion by Lunarians who have seized Mars is repelled by an Earth-Venus alliance. The novel was reprinted in Gernsback’s Amazing Stories as a three-part serial in 1926. “World peril and imaginary war against the background of Marconi’s experiments and ‘The Crystal Egg’ by H. G. Wells.” – Bleiler. “Important as an early alien invasion, the narrative’s weakness lies in its reliance upon psychic possession and warfare in terms of traditional naval weapons.” – Clareson.

- Garret Smith’s Only Between Worlds (11 October-8 November 1919 Argosy Weekly; 1929 in book form) is a semi-juvenile tale that begins on a dystopian Venus and concludes on Earth, with female protagonists plotting to conquer the world. Considered one of his weakest stories.

- Greye La Spina’s “The Ultimate Ingredient.” A Gothic horror story disguised as a mad-scientist story about invisibility. In The Thrill Book.

- Greye La Spina’s “From Over the Border” (The Thrill Book, May 15, 1919). La Spina was one of the few women to write regularly for the leading fantasy/horror pulps, and was a contributor to the very first issue of the first American pulp magazine devoted exclusively to tales of horror and the fantastic.

- Max Brand’s Children of Night (All-Story Weekly, March 22, 1919). “The Amazing Adventures of a Superman in Rogueland.” Adapted as the 1921 movie Children of the Night.

- Max Brand’s The Untamed. The original spaghetti western (complete with a Morricone-style whistling score), this yarn features a protagonist with uncanny violent abilities… leading one to wonder whether it’s a Sarah Canary-esque work of Radium Age proto-sf about a mutant or possibly an alien? One of Brand’s most famous westerns… which HILOBROW serialized in 2022 as a proto-sf novel. Followed by The Night Horseman (1920), The Seventh Man (1921), and Dan Barry’s Daughter (1923).

- H.P. Lovecraft’s “Dagon.” A Merritt-esque sf-ish story about a submerged land mass disturbed by wartime action, records of an ancient monster god. First appeared in The Vagrant, later in Weird Tales in 1923. Collected in From Wells to Heinlein (1979, ed. James Gunn).

- Homer Eon Flint’s “The Lord of Death.” (All-Story Weekly, May 10, 1919. First in a series about the interplanetary adventures of Dr. Kinney. Appeared in All-Story. Bob Davis of All-Story considered Flint one of the magazine’s most talented sf writers.

- Jean de La Hire’s Joë Rollon: L’autre homme invisible. The other invisible man. Written under the pseudonym of Edmond Cazal,

- Leslie Burton Blades’ “Fruit of the Forbidden Tree” (All-Story Weekly.) Brilliant experimental psychologists decide to plumb the secrets of the soul. “Almost unintelligible,” says Bleiler.

- Martha Bensley Bruère’s Mildred Carver, USA. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Alice Earle Chapin’s “When Dead Lips Speak” in The Thrill Book, 1 August 1919. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Susan Tweedsmuir and John Buchan’s The Island of Sheep (as by ‘Cadmus’ and ‘Harmonia’). Note: later, a totally different book was published by John Buchan under the same title. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Mary Cholmondeley’s “The Dark Cottage.” Cholmondeley was a popular but now almost forgotten writer of romances. In this story, a young, wealthy factory and land owner goes off to war in 1915, only to wake up 50 years later when a final piece of brain surgery is successful. The difficulties of his adjustment to the new world (smokeless factories, workers commuting there by personal aircraft instead of being crammed into slums hard up against the factory walls, women playing an equal if not a leading role in government, etc.) are well delineated. A period of revolution called “The Black Winter” is hinted at. What happened to his estate’s rookery? The radiation from a newly erected power station, while not harming the adult birds, destroyed their young.

- Maurice LeBlanc’s L’Île aux Trente Cercueils (1919-1920 Le Journal; 1919; trans. Alexander Teixeira de Mattos as Coffin Island. Also published as The Secret of Sarek. Set on a mysterious island in the English Channel under which a Lost World is found containing mutation-causing artifacts. The heroine of the story is Véronique d’Hergemont. Fourteen years ago her father, Professor Antoine d’Hergemont, kidnapped her baby; she was told that the two had drowned. While watching a film, Véronique spots her childhood signature “V d’H” mysteriously written on the side of a hut in the background of a scene. Her visit to the location of the film shoot deepens the mystery, but also provides further clues that point her towards long-lost relations and a great secret from ancient history — the last of Cagliostro’s mysteries. When Véronique arrives on the island of Sarek, off the coast of Brittany, the prophecy comes true. Only Arsène Lupin, who shows up near the end of the story, can save the day now.

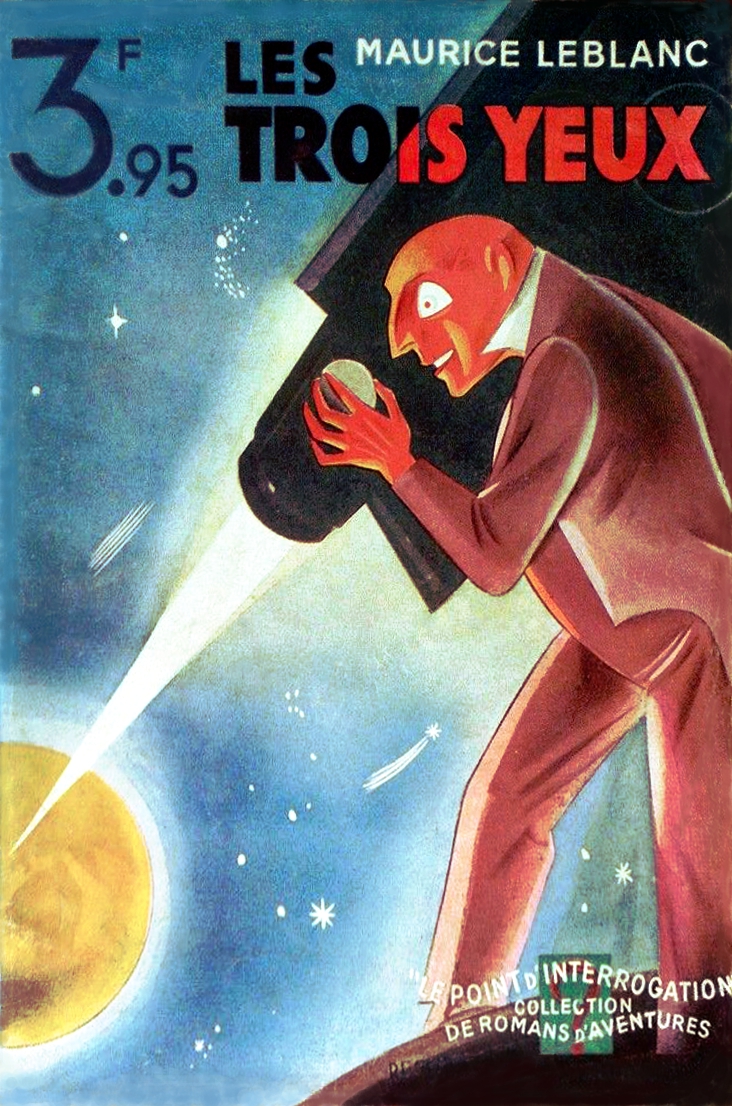

- Maurice LeBlanc’s Les trois yeux (July and October 1919, in Je Sais Tout; as book, 1920; in translation, as The Three Eyes, 1921). Describes the Invention of a Time Viewer, a chemical which, when applied to walls, shows real historical events as well as attempts at communication on the part of the three-eyed inhabitants of Venus.

- Milo Hastings’s “Children of Kultur” (True Story Magazine, May to November 1919). Published in book form as The City of Endless Night (1919/1920). Berlin in 2041 has become an entirely roofed-in city of sixty levels, sheltering 300,000,000 sun-starved humans. Since 1941 the city had held out against the World State which tried to bomb it into line. Hohenzollerns ruled this tight world; ruled it with the blessings of “autocratic socialism,” “the perfect government which we Germans have evolved from proletarian socialism.” Moskowitz: “Of the pioneering anti-Utopian novels, one of the finest and least known is City of Endless Night.” Fun fact: Hastings was an American inventor, author, and nutritionist. The word kultur, German for culture, had been made infamous by Allied propaganda in World War I<. Moskowitz compares this dystopia to When the Sleeper Wakes by Wells, Messiah of the Cylinder by Victor Rousseau, and We by Zimiatin. Some say that City of Endless Night was the original inspiration for Lang and Harbou’s Metropolis.

- Murray Leinster’s “The Runaway Skyscraper” (Argosy). Leinster’s first proto-sf story; Moskowitz mentions it in Scientific Romance. Arthur Chamberlain, an engineer who works in a midtown Manhattan office building called the Metropolitan Tower, discovers that the sun has begun moving backwards in the sky. A flaw in the rock beneath the building has caused it to subside, but instead of moving in space, the building is falling backwards into the past. When the subsidence finally ends, the building is located several thousand years in the past, and its 2000-odd inhabitants find themselves stranded in pre-Columbian Manhattan. How much did readers like it? It was reprinted in the third (June 1926) issue of Hugo Gernsback’s first science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories. Fun fact: His real name was William F Jenkins. He’d end up writing more than 1,500 short stories and articles.

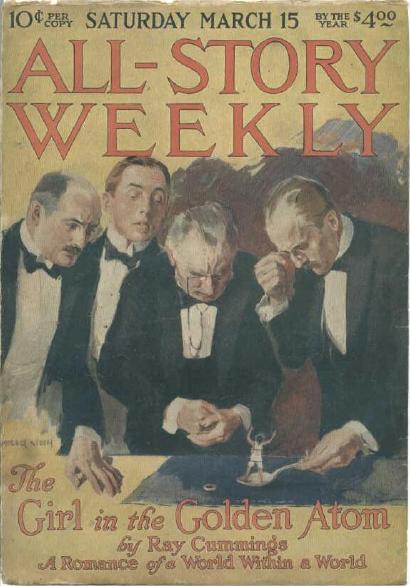

- Ray Cummings’s “The Girl in the Golden Atom” (Argosy). Cummings’s debut story, and his most highly regarded fictional work, was this one. Here Cummings combined the idea of Fitz James O’Brien’s The Diamond Lens with Wells’s The Time Machine. A sequel, The People of the Golden Atom, was published in 1920. Cummings wrote in “The Girl in the Golden Atom”: “Time… is what keeps everything from happening at once”, a sentence often misattributed to the likes of Einstein or Feynman. The 1922 novel, The Girl in the Golden Atom, is an expanded version that includes this story’s sequel. In the first part of the story (the original novelette), an unnamed chemist visits the Golden Atom, falls in love with the beautiful girl he spied on there, and helps out her people in a war with an enemy city-state. His friends follow him, and together they find a revolution, excitement, danger, and romance. The response was massive.

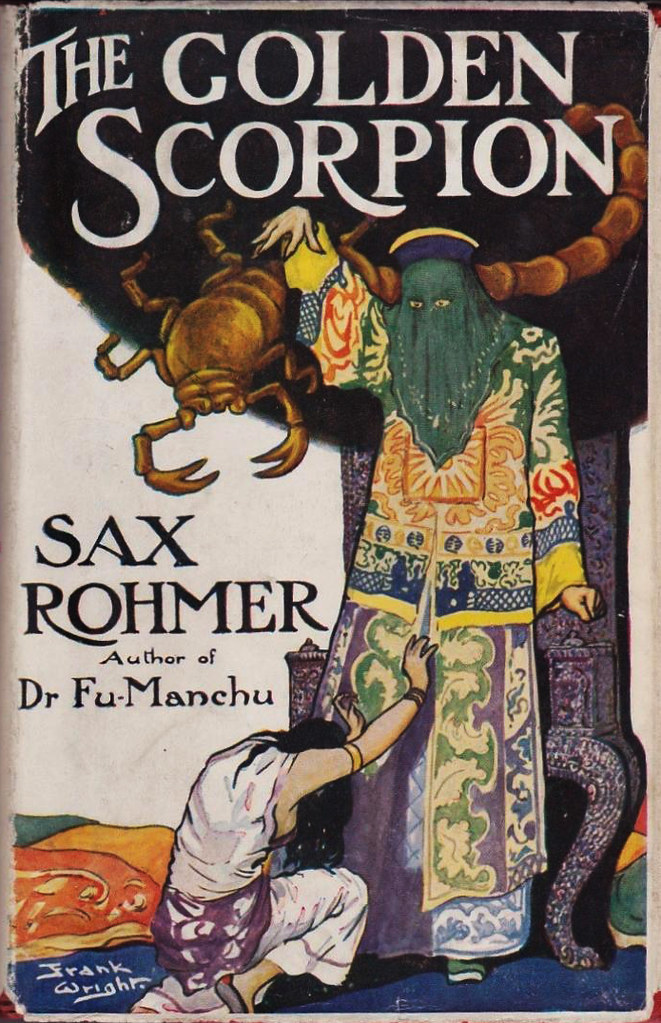

- Sax Rohmer’s The Golden Scorpion. A Fu Manchu adventure.

- Trainor Lansing’s “The Lost Days” (The Thrill Book). A drug distorts the time sense. Mentioned by Ashley.

- William Hope Hodgson’s “The Baumoff Explosive” (17 September 1919, Nash’s Illustrated Weekly). Both more religious and more scientific than many of the author’s other horror stories. The story concerns a chemist, Baumoff, who is attempting an unusual experiment. It is Baumoff’s belief that the darkening of the sky and earthquakes recorded in the Bible at the instant of the death of Jesus Christ are physical phenomenon that can not only be explained but also recreated. His attempt to accomplish this succeeds but not exactly in the way he had anticipated. The allegorical aspect of Hodgson’s novels embodies a conviction that horrid evil forces move beneath the surface of reality as it seems to our limited perception, sometimes becoming vilely manifest in creatures such as the spirit which possesses the scientist in this blasphemous fantasy. Originally written 1912.

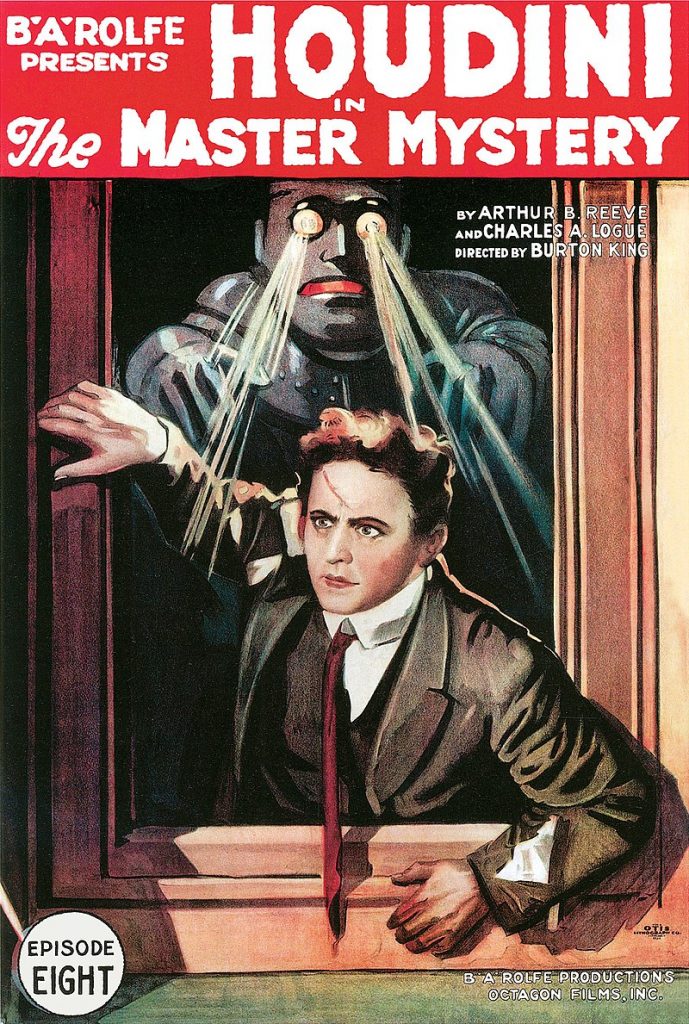

- The Harry Houdini serial The Master Mystery featured the first robot (powered exoskeleton) in film, called the Automaton.

- Michael Williams’s “The Mind Machine” (All-Story). After World War I the world is rebuilt economically, with the cartel International Power and Mechanical Company becoming very important. But strange things happen at the company’s power plants. Employees are found dead, associated with a blue unanalyzable liquid. Old Doctor Evans suggests that the “living machines” that he’d invented to handle complicated operations have thrown off the control of the Inner Circle. The machines drive humans out of the cities, which they take over. A parable warning about labor unrest?

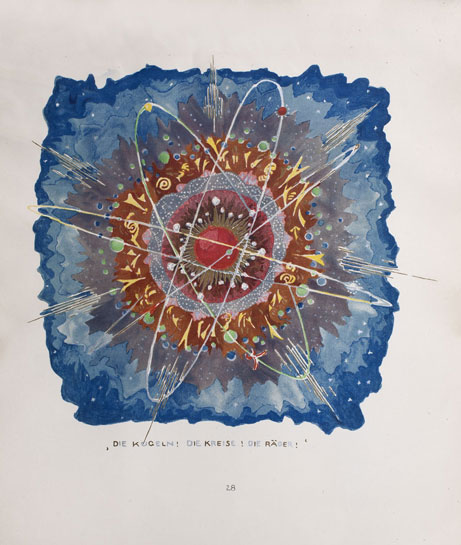

Part four, “Structures of the Earth’s Crust,” moves from the reconstruction of mountain ranges to the reworking of the entire Earth with glass architecture, and expands to Part Five, “Star Structures,” in which stars and other cosmic entities are transformed to crystalline structures. In the last pages, glass architecture seems to implode upon itself, with an illustration of an atom-like structure, with the note: “THE SPHERES! THE CIRCLES! THE WHEELS!”

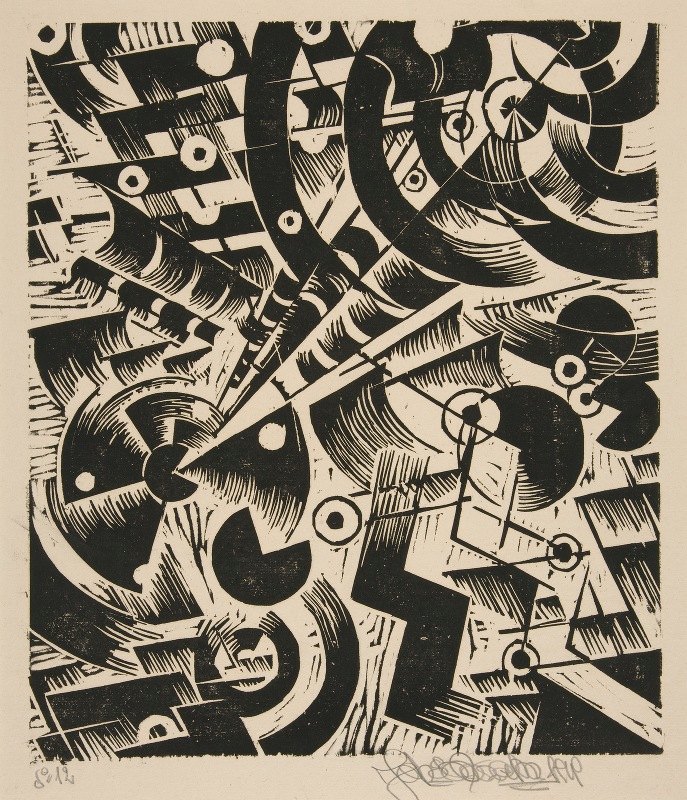

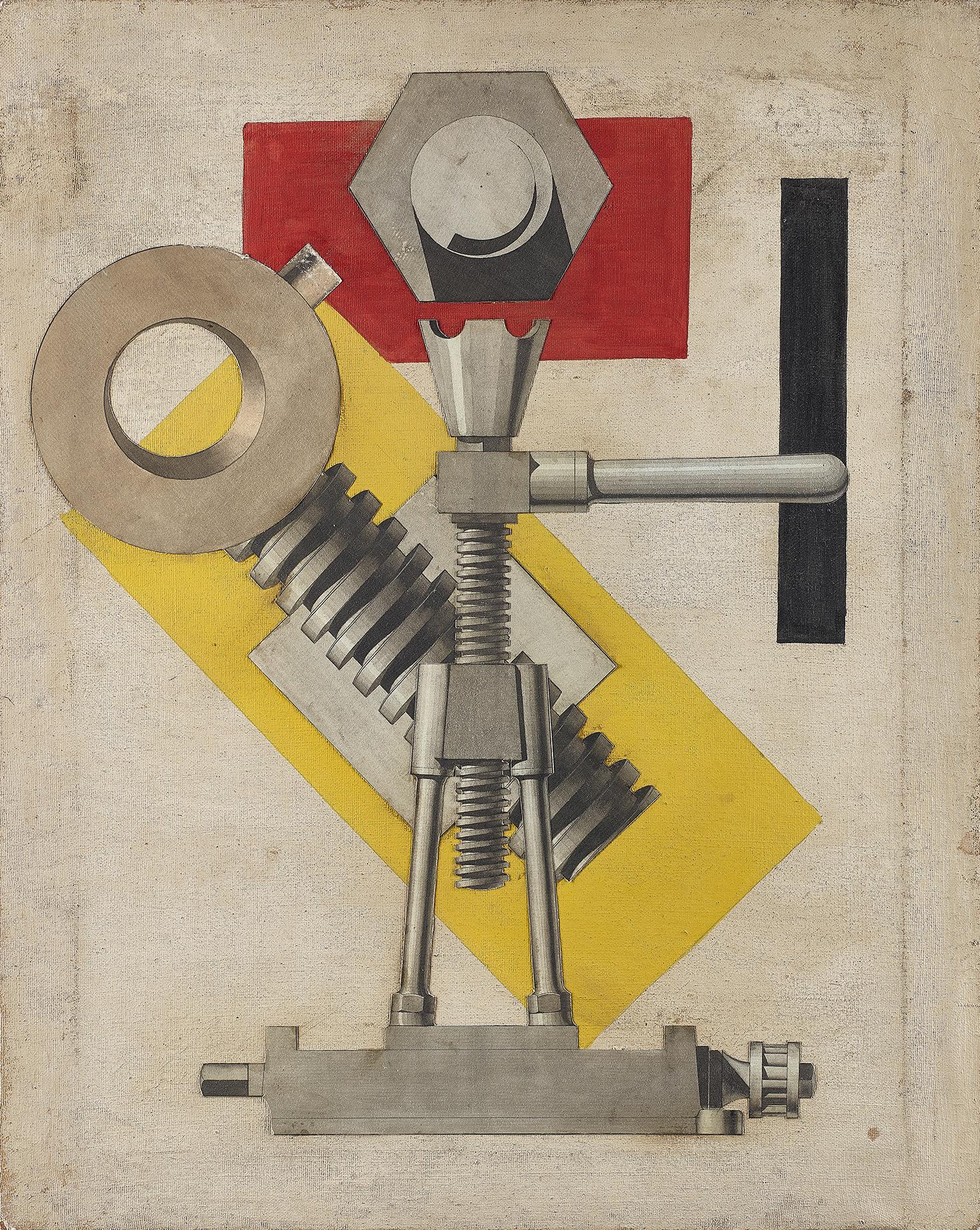

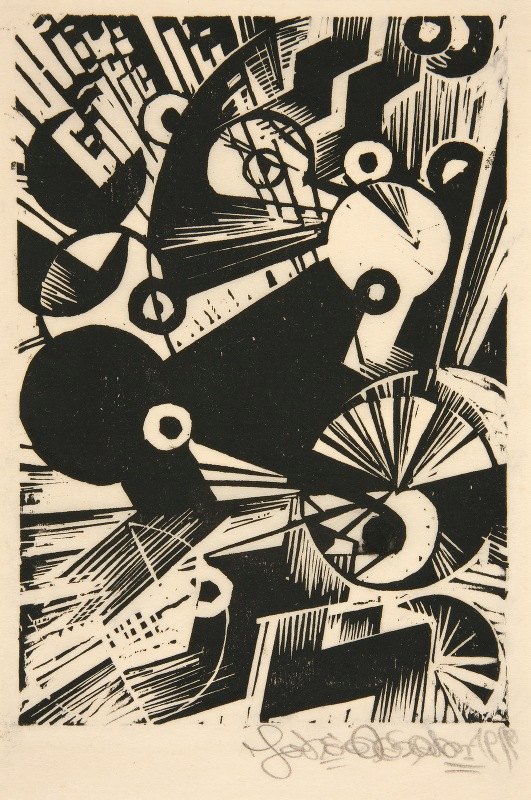

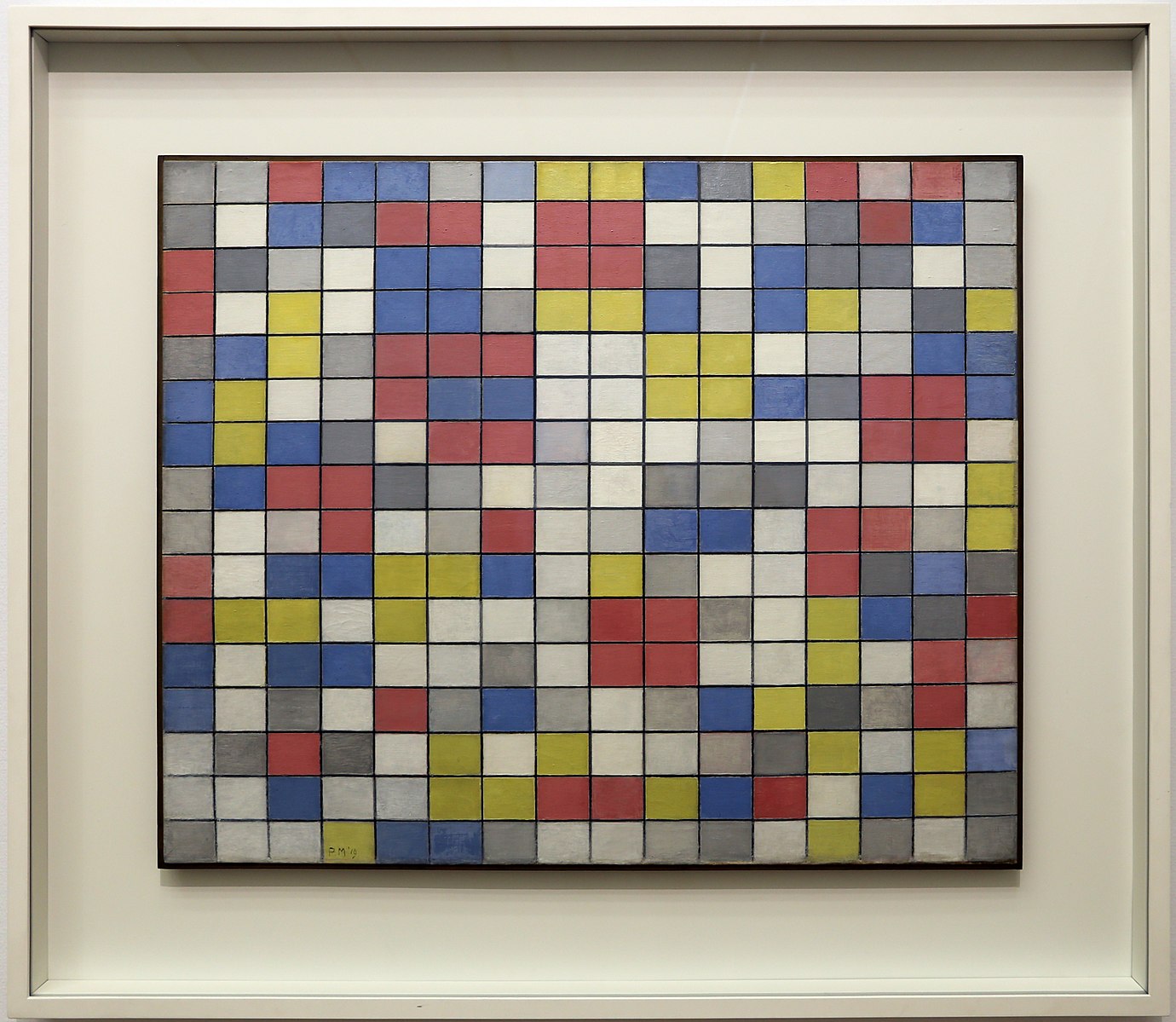

Construction no. 95 (1919)

In a 1919 “Manifesto of Absolute Expressionism,” Johannes Molzahn demanded that the artist’s work reflect the pulsating energy of the universe so it could become a symbol of the “cosmic will.”

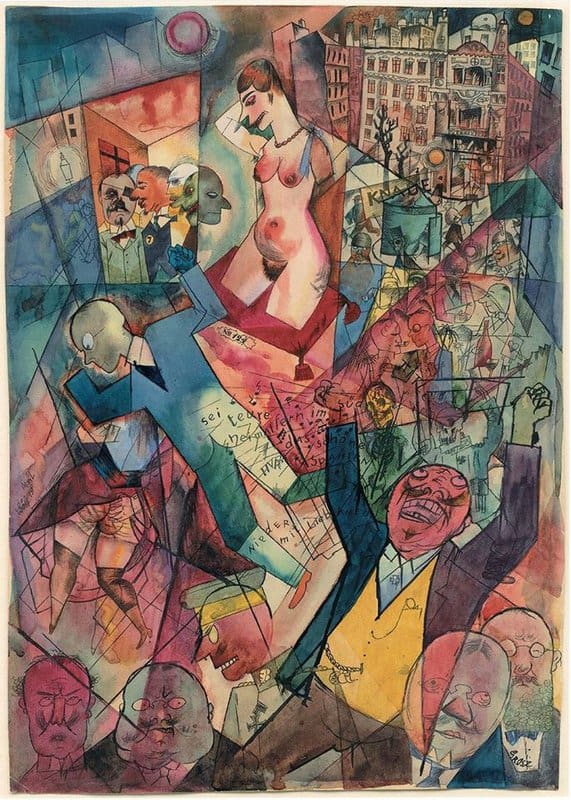

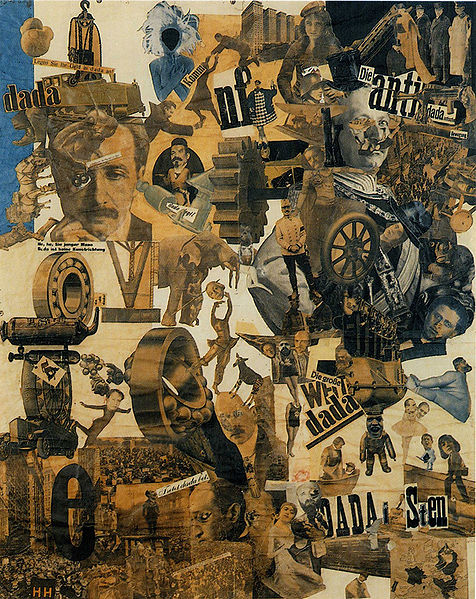

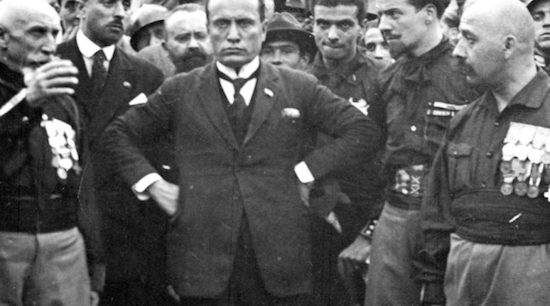

ALSO: Einstein and Minkowski’s theories reach the general public after being validated by Eddington’s observation of a 1919 solar eclipse. Aston builds mass-spectograph; Goddard’s A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes; Rutherford demonstrates that the atom is not the final building block of the universe. Browning and Thompson finalize design of their machine guns. Prohibition in the US; Wilson presides over the first League of Nations meeting in Paris; Mussolini founds Fasci del Combattimento; Third International founded at Moscow; race riots in Chicago; International Labor Conference in Washington endorses eight-hour day. Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio; Cabell’s Jurgen; Mencken’s The American Language. McCulley’s The Curse of Capistrano (also published as The Mark of Zorro), Max Brand’s The Untamed, Buchan’s Mr. Standfast. Bergson’s L’Energie spirituelle (translated as Mind Energy — a collection of essays concerned with metaphysical and psychological problems); Cassirer’s The Problem of Knowledge. “Black Sox” scandal.

Einstein’s theory of gravitation was, in early 1919, still untested. It had the curious status of being a scientific theory which was bold in its revision of existing ideas, and elegant in its proposed solution, but which had not been put to experimental proof. In England, the scientific journalist JWN Sullivan — deputy editor of The Athenaeum — wrote several essays on the beauty of Einstein’s theories. Like Poincaré, Sullivan found it valuable to think about the element of imagination in science. Which helped inspire Pound and Eliot to align poetry with science.

Karl Popper, the philosopher of science who grew up in Vienna during the heyday of the Vienna Circle — the philosophers of science who elaborated logical empiricism, which would become the dominant philosophy of science in Europe and the USA — would in 1934 develop a divergent framework for understanding scientific thought, articulated in The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Popper argues that science should adopt a methodology based on falsifiability, because no number of experiments can ever prove a theory, but a reproducible experiment or observation can refute one.

Popper claimed to have formulated his initial ideas about “the demarcation problem” — how should we distinguish science from pseudoscience? — after he learned about the British expedition to study the solar eclipse of May 29, 1919.

Three astronomers — Arthur Eddington, Frank Watson Dyson, and Andrew Crommelin — played key roles in this experiment. Eddington and Crommelin travelled to locations at which the eclipse would be total — Eddington to the West African island of Príncipe, Crommelin to the Brazilian town of Sobral — while Dyson coordinated the attempt from England. They measured the deflection of starlight around the sun in order to test a prediction from general relativity, the gravitational theory recently formulated by Einstein (see 1915). One of Einstein’s crucial tests for the theory was that strong gravitational fields (such as the sun’s) would bend the Earth-ward path of light hailing from stars — and that the curvature of light from stars located behind the solar disk could be measured precisely during an eclipse. Eddington and Dyson announced, to international fanfare, that the measured curvature from their experiment more closely adhered to Einstein’s theory than to that predicted by Newtonian gravity.

The 17-year-old Popper was struck by the risk Einstein proved willing to run in proposing a falsifiable, refutable, testable theory about starlight’s curvature during a solar eclipse. If Eddington and Dyson’s experiment hadn’t confirmed his theory, then Einstein would have been forced to abandon it.

Many supposedly scientific theories — Popper was particularly interested in Marxism and Freudianism — were at the time considered “scientific” because of verificationism, a logical empiricist theory. If it is verified by empirical data, according to this view, a theory is scientific. And indeed there was plenty of data that apparently confirmed Marxism and Freudianism. However, as conspiracy theorists and pseudoscientists could tell us, if you formulate a theory flexibly enough, then anything (or almost anything) might be interpreted as confirming it. Which is why verificationism, as a demarcation criterion, was (Popper decided, at age 17, after Eddington’s 1919 expedition) grossly inadequate. Popper instead built his demarcation criterion — widely popularized by a 1953 lecture, it remains to this day the most commonly invoked among scientists — around the courage to wager against refutation. “The criterion of the scientific status of a theory,” he insisted, “is its falsifiability, or refutability, or testability.”

If you claim to be scientific, but cannot (like Einstein was willing to do) posit conditions under which your theory would be falsified, according to Popper, then you’re a pseudoscientist.

PS: As Michael D. Gordin notes in On the Fringe: Where Science Meets Pseudoscience, Popper’s falsificationism is problematic. Just as experimental results that seem to confirm a theory don’t always constitute a confirmation, experimental results that seem to falsify a theory don’t always constitute a falsification. Because the experiment may have been poorly designed or conducted, say. (Even Eddington’s experiment wasn’t as conclusive as Eddington made it seem; it was several years before absolutely incontrovertible result in support of general relativity would be obtained.) Also, for some sciences — evolutionary biology, geology, and cosmology for example, where you’re looking at historical evidence only — you can’t make a falsifiable claim and then run an experiment. Also, what’s to stop pseudoscientists from announcing that they are prepared to change their minds if some observation (however improbable) comes to pass — and thereby meeting Popper’s criterion?

Charles Fort’s Book of the Damned.

The Book of the Damned was the first published nonfiction work by Charles Fort. Concerning various types of anomalous phenomena including UFOs, strange falls of both organic and inorganic materials from the sky, odd weather patterns, the possible existence of creatures generally believed to be mythological, disappearances of people, and many other phenomena, the book is considered to be the first of the specific topic of anomalistics.

The title of the book referred to what he termed the “damned” data – data that had been damned, or excluded, by modern science because of their not conforming to accepted belief. Fort charged that mainstream scientists are conformists who believe in what is accepted and popular, and never really search for truth that may be contrary to what they believe. He also compared the close-mindedness of many scientists to that of religious fundamentalists, implying that the supposed “battle” between science and religion is just a distraction for the fact that, science, in his opinion is in essence simply a de facto religion. This is a theme that Fort developed more in his later works, New Lands and Lo!, particularly.

Fort’s experience as a journalist, coupled with his wit and contrarian nature, prepared him for this work, ridiculing the pretensions of scientific positivism and the tendency of journalists and editors of newspapers and scientific journals to rationalize. Note that in 1915, he’d attempted to write two proto-sf novels, which never found publication.

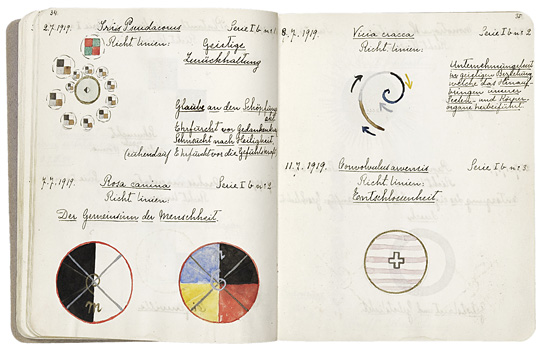

The most celebrated citadel of avant-garde design to be established in Europe in the period between the two world wars — the Bauhaus, founded by the architect Walter Gropius in Weimar in 1919 — initially billed itself as the “Cathedral of Socialism.” The school became famous for its approach to design, which attempted to unify the principles of mass production with individual artistic vision and strove to combine aesthetics with everyday function. Staff at the Bauhaus included prominent artists such as Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and László Moholy-Nagy at various points. The radicalism of the Bauhaus was in practice a more volatile and bizarre amalgam of artistic, mystical, and collectivist ideas than its socialist reputation suggests. “Its ranks were rife with the followers of occult sects, bohemian lifestyles, food cults, and sundry other manifestations of a freewheeling counterculture.” — Hilton Kramer

The “Bauhaus” artistic movement, which takes its name from the school founded by Walter Gropius in 1919, occupies a very prominent position among 20th century movements aiming at a union between art and rationality. The artists who founded it or subsequently took part in it often juxtaposed technical subjects with their artistic studies. Mathematics and geometry had a fair space in their school curriculum.

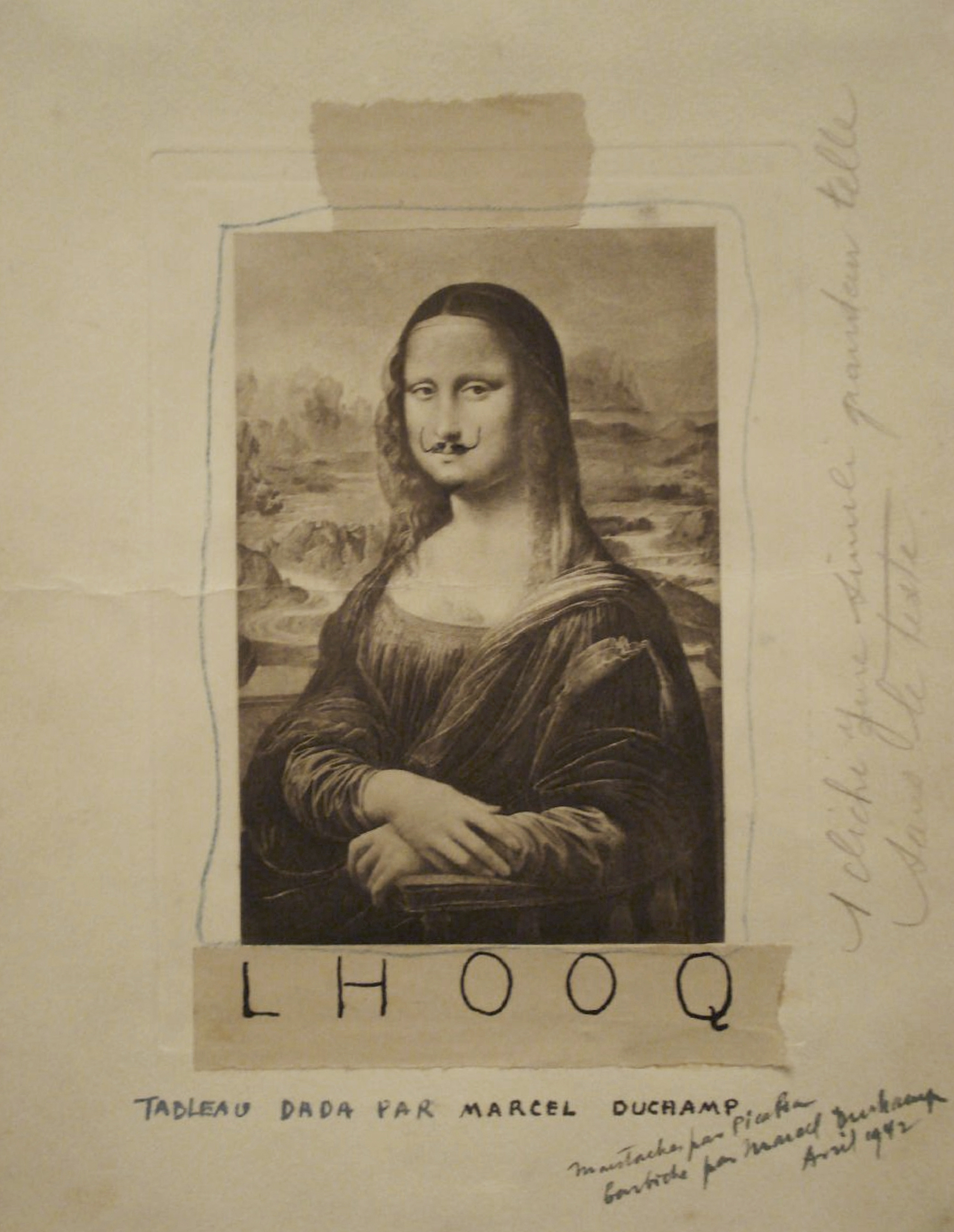

In 1919, Marcel Duchamp first conceived of L.H.O.O.Q., a “rectified ready-made” in which the objet trouvé is a cheap postcard reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Duchamp drew a moustache and beard in pencil on it, and appended the title. The name of the piece is a gramogram; the letters pronounced in French sound like a phrase meaning, essentially, “She’s hot to trot.”

In 1919, the Theosophist architect Claude Bragdon designs a house in Rochester, NY (at 404 East Ave.) on the property (400 East Ave.) of Hiram Sibley, a banker who was a founder and the first president of what became Western Union.

In 1919, shortly prior to staying at Mabel Dodge Luhan’s Taos estate, painter Agnes Pelton writes in her journal that she wants her art to begin reflecting “perfect consciousness” and “Divine Reality.” These words were lifted from the writing of Blavatsky. Like Hilma af Klint, to whom she has recently begun to be compared, Pelton used abstraction to convey her vision of a reality beyond the material world.

The composition is a succession of sequences made up of small rectangles of different colors that finds a moment of comparative rest in the larger rectangles. The ephemeral progression of new events (the small rectangles) is transformed in the larger units into a space of relatively greater duration.

Mondrian: “The unchangeable (the spiritual) is expressed in the composition by means of straight line or planes of non-color (black, white, and gray), while the changeable (the natural) is expressed by means of planes of color and rhythm.”

For Mondrian yellow, red, and blue constitute a “plastic” symbol of the purest and most intense colors in the world. He uses the three primary colors here to express contrast and diversity, and white, black, and gray to produce an equally broad range of variation that appears, however, more homogeneous than the contrasting variation generated with the primary colors.

The human search for unity (be it the idea of a God or the unifying theories of science) is always counterbalanced by the multifarious aspect of nature and by the unforeseeable evolution of life. Checkerboard with Light Colors presents both aspects.

The black and white unity now opens up to the variety of intermediate hues (yellow, red, and blue); the colors of the spirit open up to the three primary colors that symbolize the natural world in the Neoplastic language.

The opening up of black and white to the primary colors will be the guiding motif of Mondrian’s subsequent work, from 1920 up to 1942.

The dynamic and multiform aspect of natural and/or urban space is transformed on the canvas into a whole endowed with greater synthesis and equilibrium before returning to a dynamic state. The canvas serves as a model of space in equilibrium between disharmonies of real space and harmonies of plastic space.

Ernst Jentsch set out the concept of the uncanny later elaborated on by Sigmund Freud in his 1919 essay Das Unheimliche, which explores the eeriness of dolls and waxworks. For Freud, the uncanny locates the strangeness in the ordinary.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin