RADIUM AGE: 1917

By:

August 16, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

If we were to divide the Radium Age into quarters, 1917 would be the final year of its second quarter (1909-1917). How might we characterize this sub-era? Something for me to think about.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1917.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1917, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: ENERGY GUN | RAY GUN (in a description of Frank Lloyd’s movie ‘The Intrigue’) | SUPERVILLAIN.

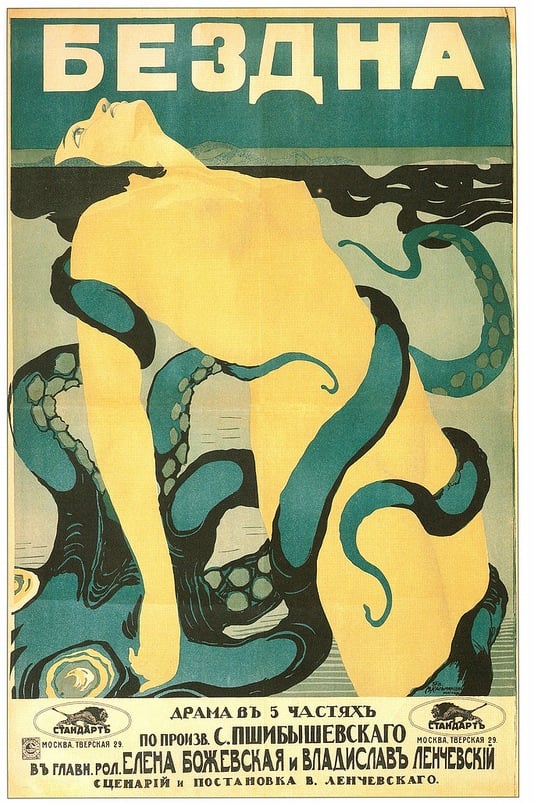

- J.A. Mitchell’s Drowsy (1917). Cyrus Alton, a telepath nicknamed Drowsy because of his drooping eyelids, grows up to attend MIT and become a brilliant scientist. (Call it: psi-fi.) He invents a spaceship equipped with an antigravity mechanism, and flies to the moon, returning with a fantastic diamond… and then, impelled by a psychic bond with a childhood sweetheart, rescues her before she joins a convent. Of greater interest than these rather silly adventures, though, is Mitchell’s account of Drowsy’s childhood. Is he the first of a new species: homo superior? Like the title character of J.D. Beresford’s Hampdenshire Wonder, young Drowsy’s evolved worldview offends his narrow-minded elders. Especially when, for example, he cuts his favorite illustrations out of a Bible; or insists on the morality of untruths; or demands to know why “teacher doesn’t tell us things worth knowing.” Like Daniel Clowes’s Enid Coleslaw, that is to say, Drowsy is a cranky middle-aged freethinker in a child’s body. Fun fact: The author, a Harvard dropout and idler, founded the original LIFE Magazine, later purchased by Henry Luce, in 1883.

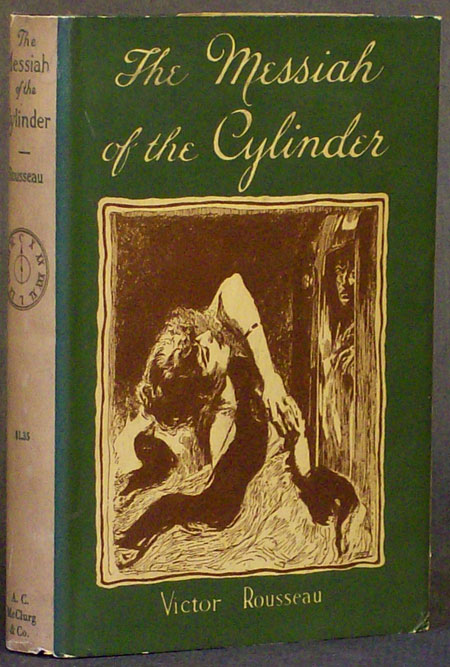

- Victor Rousseau’s The Messiah of the Cylinder (1917). After sleeping for a century, Rousseau’s protagonist, Arnold Pennell, awakens — like the protagonist of H.G. Wells’s The Sleeper Wakes (1910) — in a socialist, “scientific world freed of faith and humanitarianism.” He is horrified not only by the dazzling, skyscraper-dominated London of the future, but by Britain’s tyrannical utopian order, which is maintained though constant sloganeering and other forms of thought control. Having become an iconic figure to the people of the future, who have been waiting for a Messiah to restore to them their ancient liberties, Pennell leads a revolution — the goal of which is to help Russia restore a moralistic aristocracy in Britain. Serialized, from June–September 1917, in Everybody’s Magazine, The Messiah of the Cylinder is considered one of the first American dystopian stories. It is also one of the first sf stories to use the term “ray gun.” Bleiler says: “A more considerable work than is generally recognized, despite the pulp adventure aspects. One can find among the author’s ultraconservative values such Orwellian anticipations as omnipresent slogans, euphemistic terms for horrible institutions, the artificial language Spikisi, the mechanics of thought control, and the apparatus of the police state.” OK, it’s too Catholic, too pulp, too imitative… yet its fully realized presentation of a socialist dictatorship in the future is brilliant.

- Henry Herbert Knibbs’s “The Forgotten Land” (in The Popular Magazine). About the last white man and woman after the conquest of the US by Japanese invaders. (Some believe that Edgar Rice Burroughs may have assisted the author in the story’s plot as a favor since he was as admirer of Knibbs’s western poetry. The poetry-spouting Jack London-esque vagabond Bridge, in Burroughs’s The Mucker, is quoting Knibbs.) Moskowitz calls it a minor masterpiece.

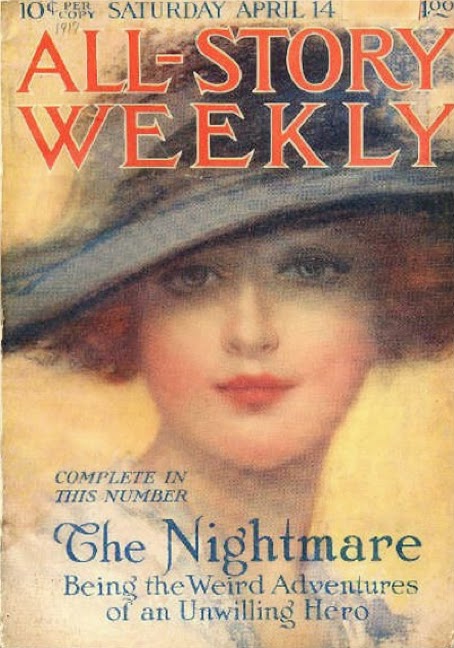

- Francis Stevens (Gertrude Barrows Bennett)’s “The Nightmare” (14 April 1917 All-Story Weekly). A 34,000-word novellete set in a surreal Lost World embedded in a Pacific island with a storyline that sometimes prefigures the 2004–2010 TV series Lost. The author’s first story since “The Curious Experience of Thomas Dunbar” thirteen years earlier, and her first under the pseudonym Francis Stevens. “The Nightmare” opens in a stateroom on board the RMS Lusitania, but by the bottom of page two, the protagonist, Mr. Roland C. Jones of New York, New York, is swimming for his life. (The Lusitania was sunk May 7, 1915, by a German U-boat — off the southern coast of Ireland.) He lands on a volcanic South Seas island, and from there is off on an adventure involving two rival Russian brothers — Prince Sergius the nihilist (in the Russian political sense) and Prince Paul the czarist — and their quest for a kind of philosopher’s stone. (The brothers are also rivals for the affections of an American nurse, Miss Weston.) On Joker Island there are labyrinthine caves, humongous and deadly cabbages, malodorous mushrooms, giant bats, enormous spiders, and other horrors. A cross between Edgar Rice Burroughs and Jules Verne, perhaps. Moskowitz’s Scientific Romance says that the air of mystery and atmospheric buildup are superbly done.

- Algernon Blackwood’s Day and Night Stories. Collects fifteen supernatural stories including the excellent “The Other Wing” and “A Victim of Higher Space” (1914), the last John Silence story. See 1914.

- Gertrude Atherton’s The White Morning: A Novel of the Power of the German Women in Wartime (short version December 1917 McClure’s, expanded version dated 1918 but 1917). Set in the very near future. German women arrange a simultaneous behind-the-lines demolition of German war materiel, bring down the patriarchical monarchy, establish a left-wing government under the control of their female leader, and end World War One. This averts the suicidal consequences of a punitive settlement, in which “the conquerors … would show no mercy.” Fun facts: Atherton (1857 – 1948) wrote several novels, including the bestseller Black Oxen (1923). She also wrote stories and articles for magazines and newspapers on feminism, politics, and war.

- Karel Čapek’s Bozí muka (Wayside Crosses), a story collection. Concerned with how one experiences the absolute. Not exactly proto-sf; but it draws on some of the same esoteric, Neo-Platonic sources of some of the era’s most far-out proto-sf. These metaphysical tales involve discovering our spiritual limitations and appreciating our sense of mystery. Like most of Čapek’s stories, these are searching tales about searches, sometimes detective stories that do not follow the rules and do not have solutions, that are about a different sort of detection. Others are about apparent miracles that have no explanations. When answers are found, they are sudden, fleeting moments of intuition that cannot be communicated. Some of the stories also represent Čapek’s first attempts at literary cubism. See 2002 translation by Norma Comrada.

- Alice Brown’s “The Flying Teuton.” Republished in 2015 by Mike Ashley in The Feminine Future: Early Science Fiction by Women Writers.

- Perley Poore Sheehan’s Blood and Iron: A Play in One Act (October 1917 Strand) with Robert Hobart Davis. A German mad scientist transforms the fatally wounded Soldier 241 into one of the first modern physically “improved” cyborgs in sf. By the author of the Captain Trouble stories, not to mention Monsieur de Guise, Kwa and the Beast Men, and more.

- Philip M. Fisher’s “The Demise of Professor Manried.” The author’s first first work of proto-sf. For All-Story Weekly, 18 August 1917. The eponymous professor is able to use electricity to amplify and harness thought waves. Also see his 1922 story about vibrational frequencies marking the difference between coexistent parallel worlds: “Worlds Within Worlds.”

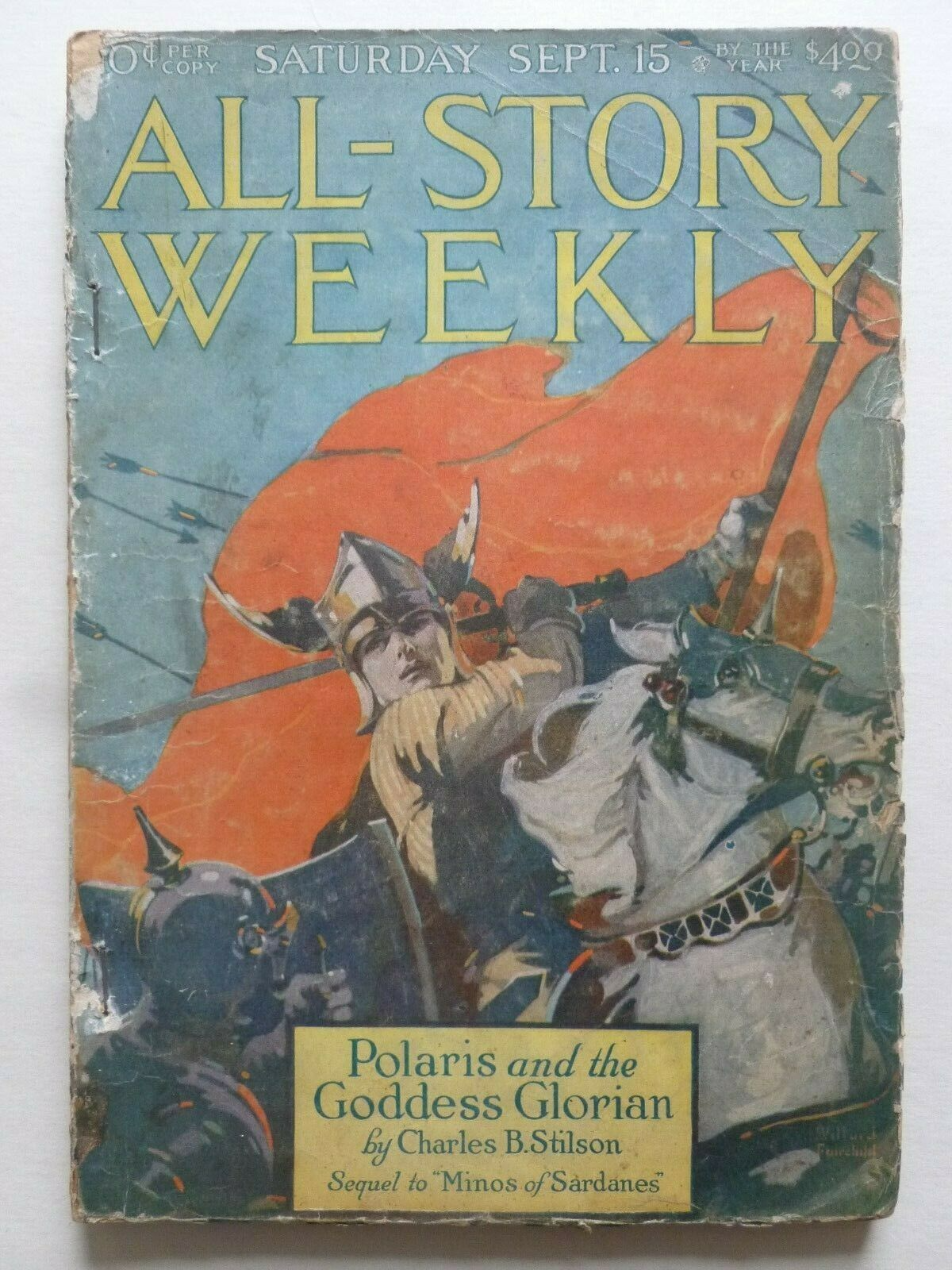

- Charles B. Stilson’s Polaris and the Goddess Glorian (15 September-13 October 1917 All-Story. A Burroughs-inspired proto-sf/fantasy novel that serves as a sequel to Polaris of the Snows (1915-1916 All-Story) and Minos of Sardanes (1916 All-Story). This one — which takes place in an underwater lost kingdom — would be published in book form as Polaris and the Immortals. Moskowitz in Scientific Romance says it’s a scientific romance in the finest Burroughs tradition, with a high degree of originality.

- Richard Dehan [Clotilde Graves]’s “The Great Beast of Kafue.” Clotilde (‘Clo’) Graves (1863–1932) was born at Buttevant Castle, Co. Cork, and published her first novel at the age of forty-six, under the pseudonym ‘Richard Dehan’. Republished in 2015 by Mike Ashley in The Feminine Future: Early Science Fiction by Women Writers.

- Julian Hawthorne’s The Cosmic Courtship. An interplanetary romance story — and one of the earliest space operas — that opens in NYC in 2001. Written by Nathaniel Hawthorne’s son. Moskowitz in Scientific Romance says the styl is stilted Victorian. Hawthorne, who was in his 70s when he wrote the book, was a follower of the philosophy of Emanuel Swedenborg whose beliefs, particularly in the potential of the mind for psychic projection, telepathy and astral travel, can be found here. Everyone has individual flying belts, and there is equality amongst the sexes. Experiments with matter transmission develop a form of astral travel which leads to adventures on Saturn.

- Arthur Machen’s The Terror, a quasi-sf horror story in which animals turn en masse against humans. Turns out that this may have something to do with a “Z Ray” developed by German scientists in order to send homicidal thoughts via the psychic ether to England. Or perhaps it is instead a “contagion of hate” born out of WWI that’s influencing the animal kingdom. “The most interesting of Machen’s later weird tales.” — Barron (ed), Horror Literature. Excerpt: “Common sense tells us that Achilles will flash past the tortoise almost with the speed of the lightning; the inflexible truth of mathematics assures us that till the earth boils and the heavens cease to endure the Tortoise must still be in advance; and thereupon we should, in common decency, go mad. We do not go mad, because, by special grace, we are certified that, in the final: court of appeal, all science is a lie, even the highest science of all; and so we simply grin at Achilles and the Tortoise, as we grin at Darwin, deride Huxley, and laugh at Herbert Spencer.” Lovecraft: “Machen is a Titan—perhaps the greatest living author—and I must read everything of his.” (to Frank Belknap Long, 3 June 1923). Also: “…there is in Machen an ecstasy of fear that all other living men are too obtuse or timid to capture, and that even Poe failed to envisage in all its starkest abnormality. As you say, he is greater than our Eddie in ability to suggest the unutterable; tho’ I cannot call him so great as an artist generally, since his narration lacks the relentless force and unified impressiveness which make any work of Poe one concentrated delirium. (to Frank Belknap Long, 8 January 1924).

- J.-H. Rosny aîné’s L’Énigme de Givreuse [The Enigma of Givreuse]. About a fissiparous human being, divided into two totally similar individuals, each naturally believing himself to be the original.

- L. P. Gratacap’s The End: How the Great War Was Stopped. World War One is stopped by the divine intervention of God and the risen dead — who terrify the living into stopping the war. The SFE says of Gratacap: “His books are overlong, choked by his compulsive didacticism, and nearly unreadable today.”

- Coutts Brisbane’s “Better Dead.” Concerns television.

ALSO: WWI raging — US enters in April; German air attacks on London. February and October Revolutions in Russia; the czar abdicates. Balfour Declaration for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” Mata Hari executed as a spy. Eliot’s Prufrock and Other Observations. Freud’s Introduction to Psychoanalysis, Jung’s Psychology of the Unconscious. Grosz’s “Ruling Class” lithographs. Bobbed hair trend sweeps Britain and US.

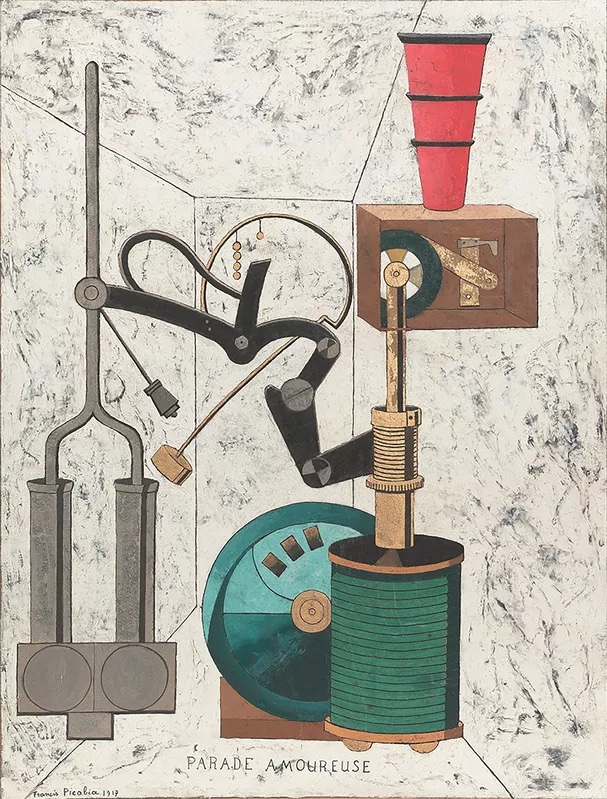

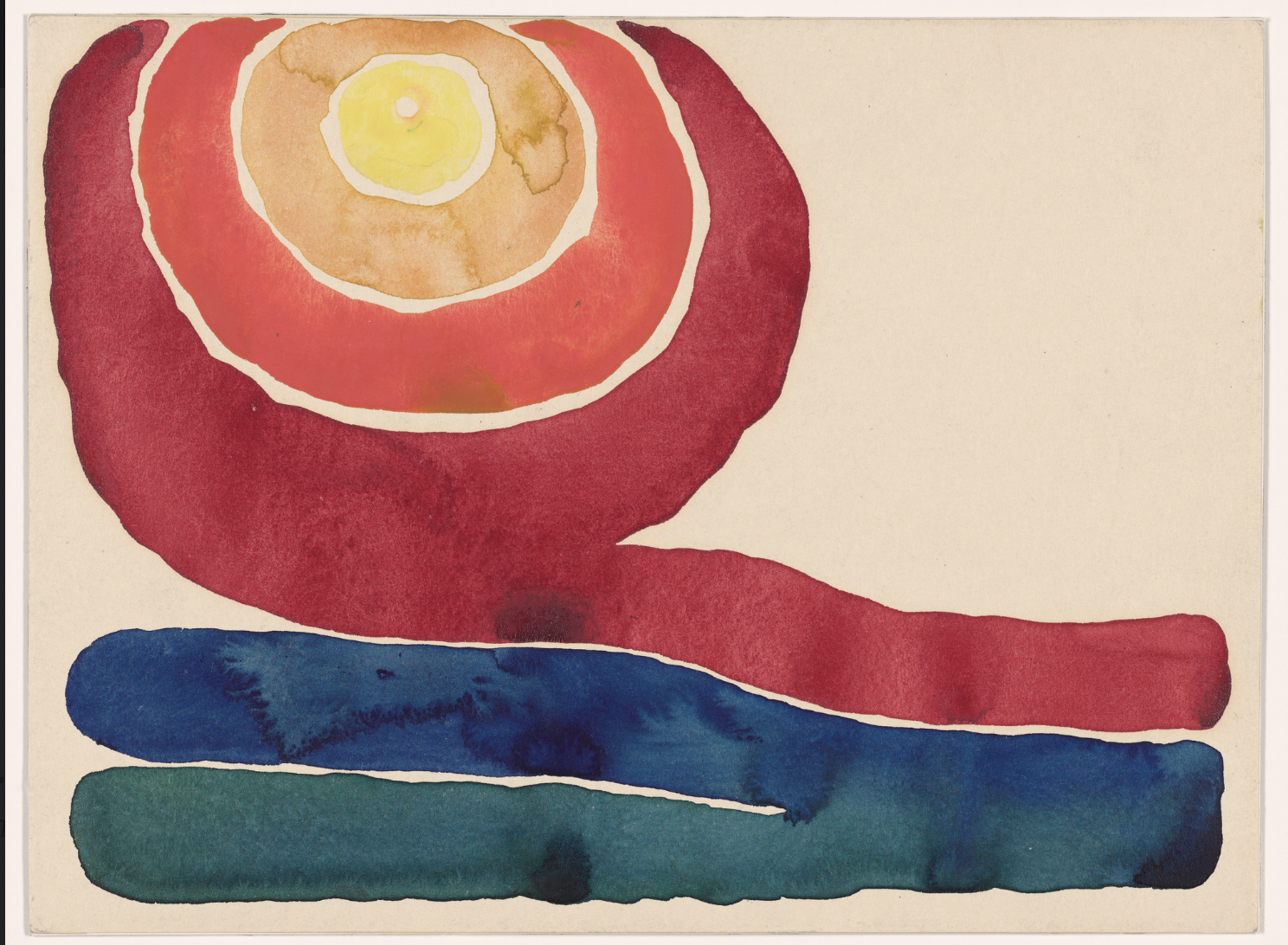

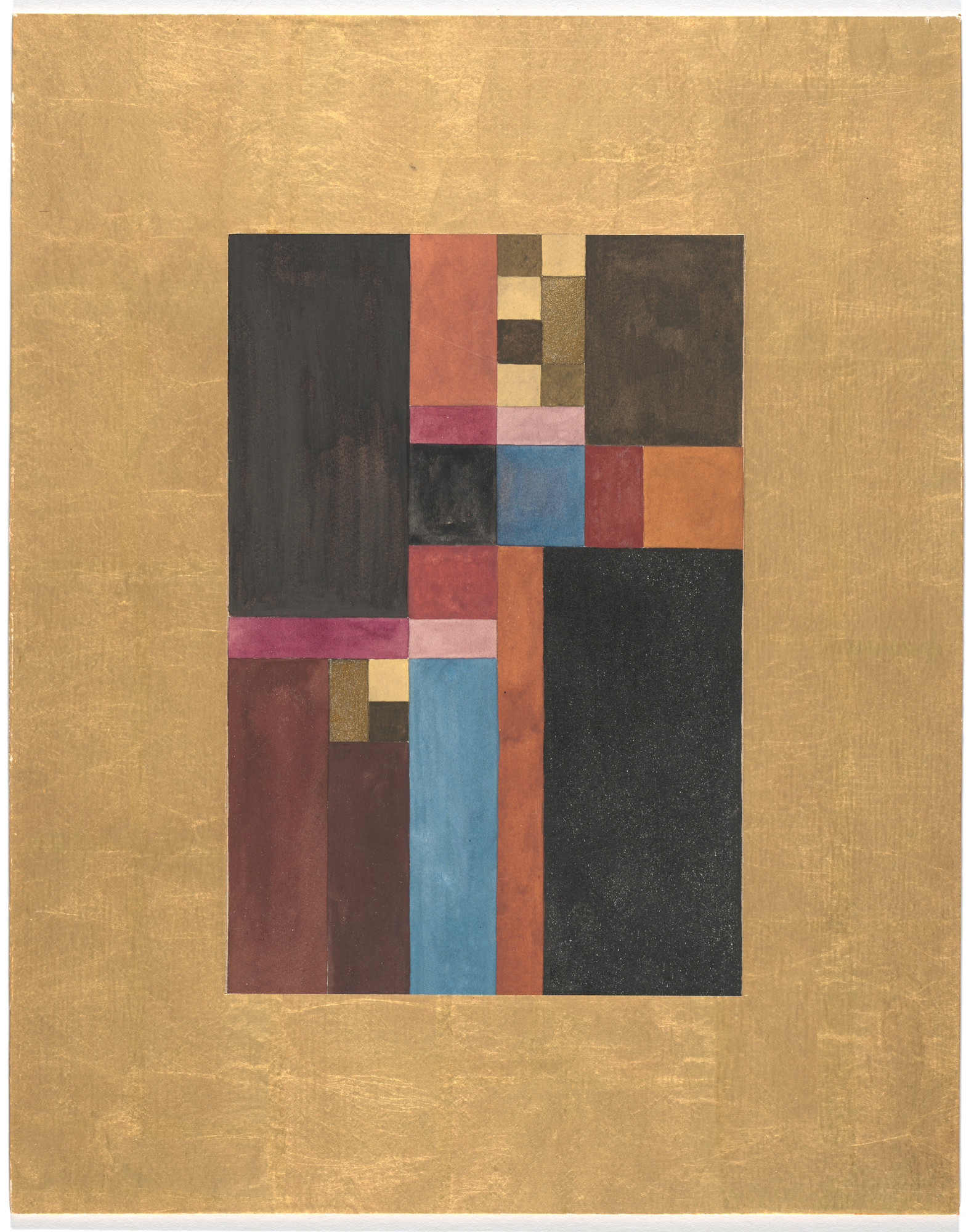

The avant-garde movement De Stijl (the Style) that Mondrian and other artists founded in 1917 was more than an art movement, Hilton Kramer points out. “Its ambition was to redesign the world by imposing straight lines, primary colors, and geometric form — and thus an ideal of impersonal order and rationality — upon the production of every man-made object essential to the modern human environment. Rejecting tradition, it envisioned the rebirth of the world as a kind of technological Eden from which all trace of individualism and the conflicts it generates would be permanently banished.” Where did these ambitious ideas come from? Chiefly from the Dutch writer and mystic M. H. J. Schoenmaekers. Like Kandinsky and Malevich, Mondrian was heavily influenced by theosophy.

P.D. Ouspensky’s A New Model of the Universe published in 1917; it is an attempt to reconcile ideas from natural science and religious studies with esoteric teachings in the tradition of Gurdjieff and Theosophy. It was assumed that the book was lost during the Russian Revolution that began that same year, but it was republished in English (without Ouspensky’s knowledge) in 1931.

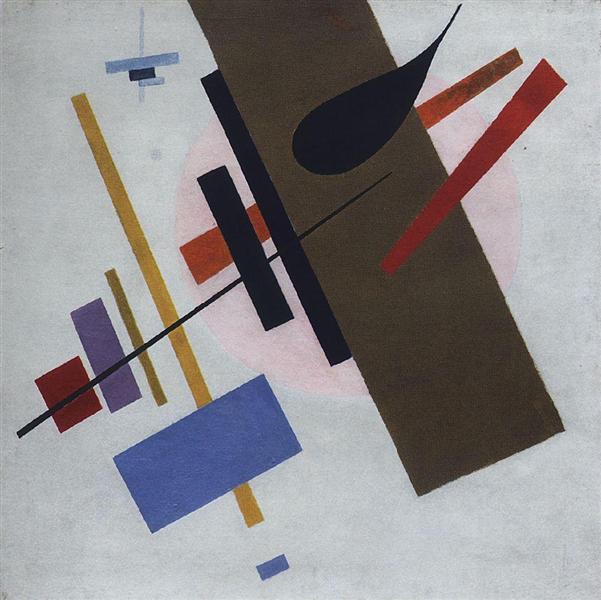

Russia c. 1917. The Russian avant garde is a constellation of artists that contributed to Russia’s cultural renovation just before and after the Revolution. Several individuals and groups explored nonobjective painting (art that does not represent or depict any identifiable person, place or thing). One thinks of the Improvisations and Compositions of Kandinsky, the Suprematism of Ivan Kliun and Kazimir Malevich, the Painterly Formulae of Mansurov, the architectonic paintings of Popova, and the Constructivist paintings of Rodchenko.

Only one of the major avant-garde painters, Kandinsky, maintained a consistent and studious interest in psychic phenomena, arguing that any investigation into the creative process must be undertaken with the help of both scientists and occultists.

William Barrett, scientist and cofounder of the Society for Psychical Research, suspected that some psychical phenomena might be explained as the interventions of invisible, immaterial beings — not souls or ghosts, but natural, living creatures. In On the Threshold of the Unseen (1917) he wrote that “it is not a very incredible thing to suppose that in the luminiferous ether (or in some other unseen material medium) life of some kind exists”. He imagined such beings to be “human-like, but not really human, intelligences — good or bad daimonia they may be, elementals as some have called them.” More info.

From 1917 to 1926, U.S. Radium Corporation, originally called the Radium Luminous Material Corporation, was engaged in the extraction and purification of radium from carnotite ore to produce luminous paints, which were marketed under the brand name “Undark”. The ore was mined from the Paradox Valley in Colorado and other “Undark mines” in Utah. As a defense contractor, U.S. Radium was a major supplier of radioluminescent watches to the military. Their plant in Orange, New Jersey, employed as many as three hundred workers, mainly women, to paint radium-lit watch faces and instruments, misleading them that it was safe.

The inventor of radium dial paint, Dr Sabin Arnold von Sochocky, died in November 1928, becoming the 16th known victim of poisoning by radium dial paint.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin