RADIUM AGE: 1915

By:

July 30, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

Until WWI the pulps ran the whole range of fiction, seeking to appeal to a wide audience, but from 1915 onwards a new generation of specialist pulps emerged. There were no magazines that specialized in a single genre until 1915, when Street & Smith brought out Detective Story Magazine.

With Street & Smith setting the lead and the success of Munsey’s titles, the post-war period saw an explosion of pulp magazines across America, with an increasing number becoming specialist. The big three fields were westerns, detective stories, and romance. Street & Smith would lead the way with all three — cf. Western Story and Love Story.

The first magazine to print only sf (and no fantasy) would be Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories — see 1926.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1915.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1915, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: VISIPHONE (in H.S. Keeler’s “John Jones’s Dollar”).

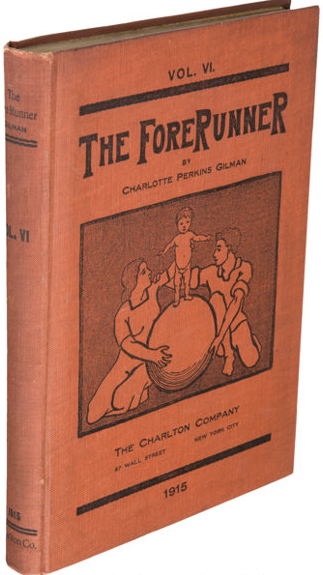

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland (1915, serialized in The Forerunner). Charlotte Perkins Gilman, sociologist and author best known for “The Yellow Wallpaper,” here gives us a Lost Race story — in which the Lost Race is composed of women who reproduce without the aid of men. When young Van Jennings and his friends — Terry and Jeff — invade an isolated society composed entirely of women, they carry with them not only brightly colored scarves and beads but sexist ideological baggage. Jeff is an idealist who regards women as things to be served and protected; Terry is a cynic who views women as conquests. Van, a sociologist, is uniquely able to apprehend the social construction of gender roles… and the fact that a woman-only social order is superior in every way to western civilization. The three men attempt to flee, but in vain. Will they be reeducated? Fun fact: The most famous feminist fantasy of the period. Herland was serialized here at HILOBROW.

- Louis Pope Gratacap’s The New Northland. A Lost Race of Hebrew-speaking dwarfs inhabits a clement hollow in the Arctic, where their possession of vast amounts of radium seals their fate, for the protagonist decides that these riches must be exploited.

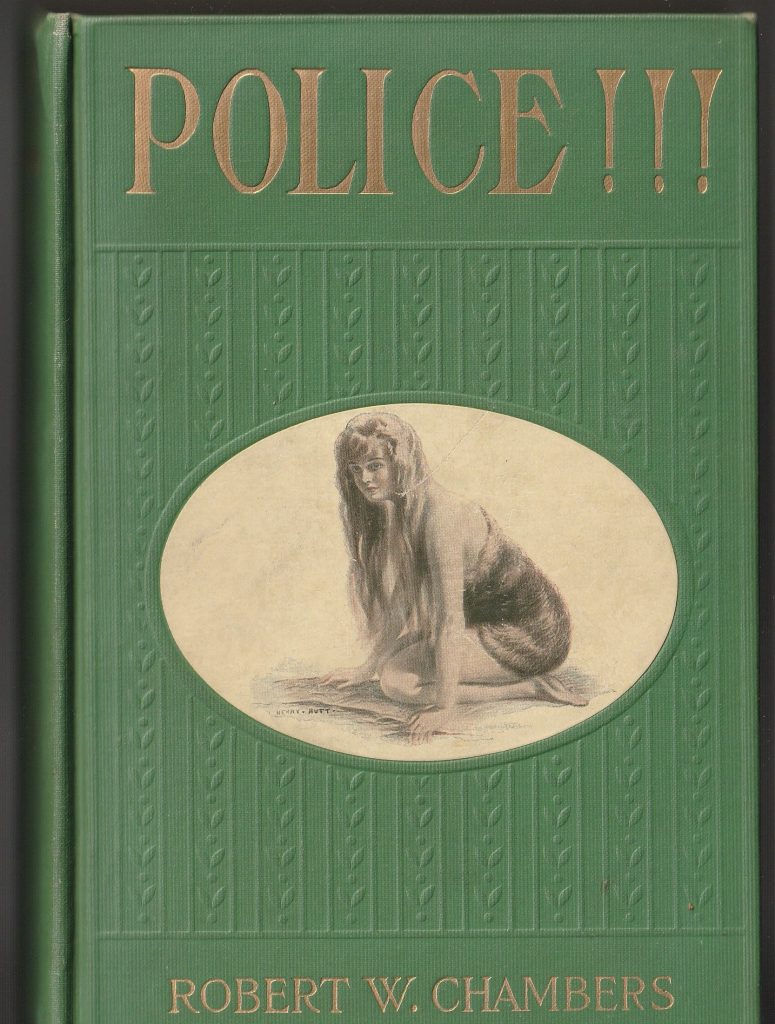

- Robert W. Chambers’s Police!!! – stories about a zoologist who encounters monsters. Part of his Lost Species sequence; see 1904’s In Search of the Unknown collection.

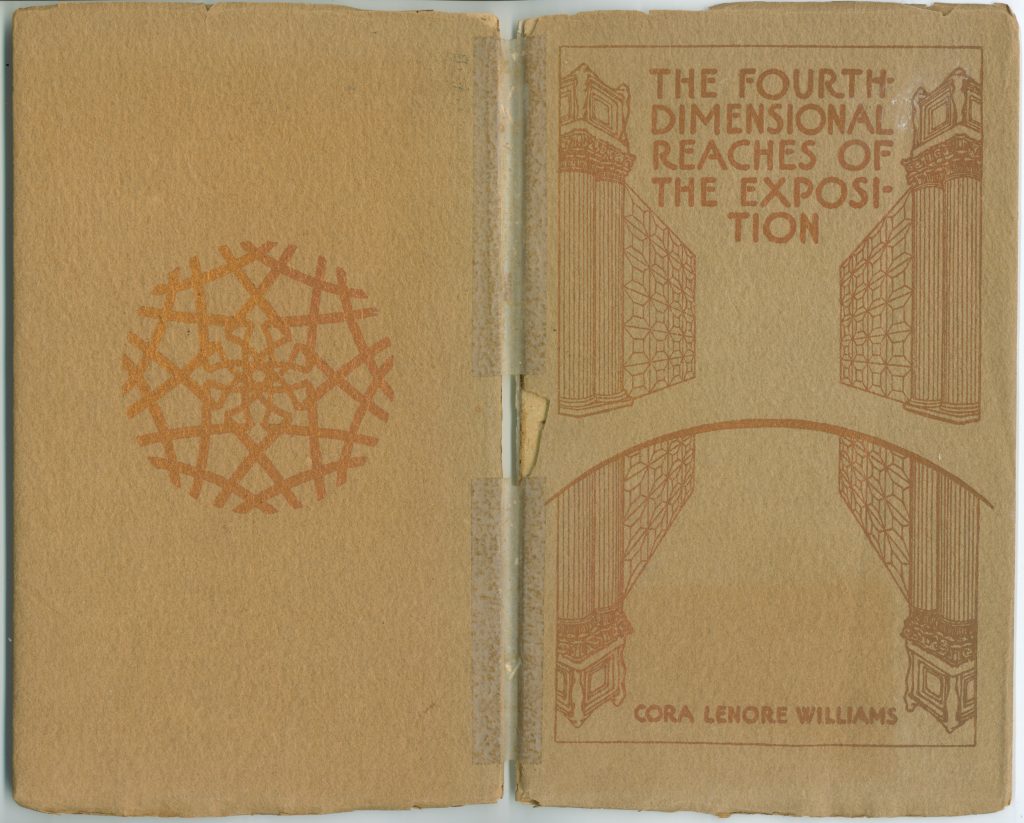

- P.D. Ouspensky’s Kinema-drama (The Strange Life of Ivan Osokin). The author was a Russian mathematician who championed the esotericist Gurdjieff; it was his conviction that most of our ideas are not the product of evolution but the product of the degeneration of ideas which existed in the past… or are still existing somewhere in “much higher, purer and more complete forms.” (He was also a proponent of the notion of a fourth dimension.) This novel follows the struggle of Ivan Osokin to correct his mistakes when given a chance to relive his past; alas, Osokin discovers that without help breaking one’s ingrained, “mechanical” behavior, one is doomed to repeat the same mistakes forever. Published in English in 1947, it’s the original Groundhog Day.

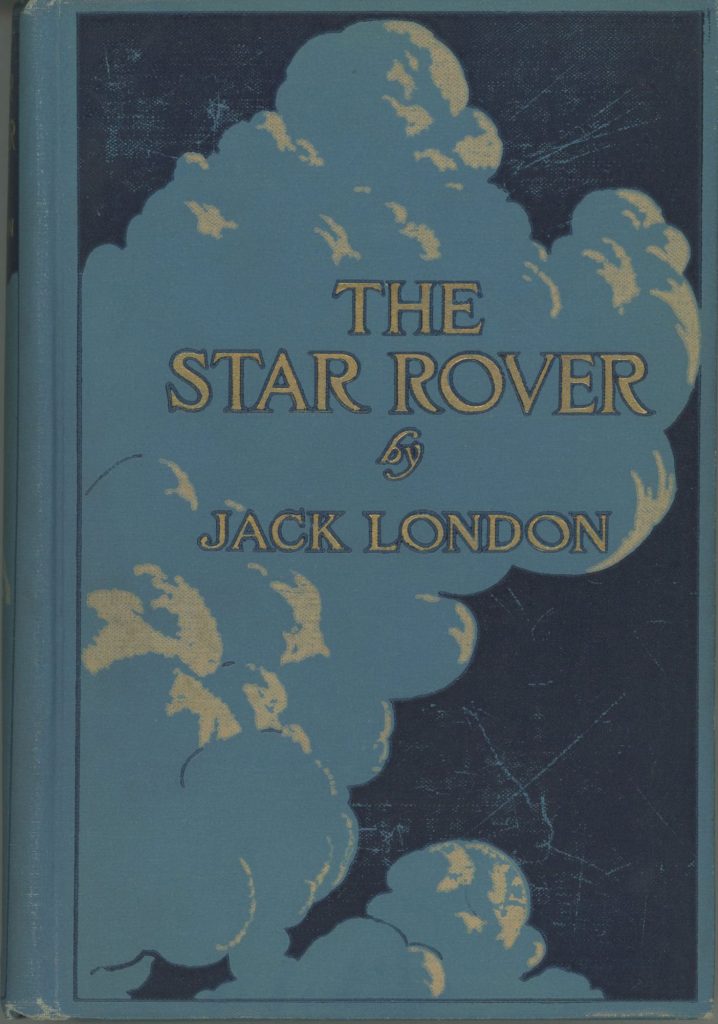

- Jack London’s The Star Rover. Serialized 14 February-10 October 1914 in the Los Angeles Examiner; as a book in 1915. Proto-sf that involves both mysticism and reincarnation. A framing story is told in the first person by Darrell Standing, a university professor serving life imprisonment in San Quentin. Prison officials try to break his spirit by means of a torture device called “the jacket.” Standing discovers how to withstand the torture by entering a trance state in which he walks among the stars and experiences portions of past lives: “I trod interstellar space, exalted by the knowledge that I was bound on vast adventure, where, at the end, I would find all the cosmic formulae and have made clear to me the ultimate secret of the universe.” The accounts of these past lives form the body of the work; they are a series of powerfully written, but disconnected and unresolved, vignettes set in different ages and cultures. Lovecraft was a fan of this story. Fun fact: A silent film based on The Star Rover was released in 1920, starring Courtenay Foote.

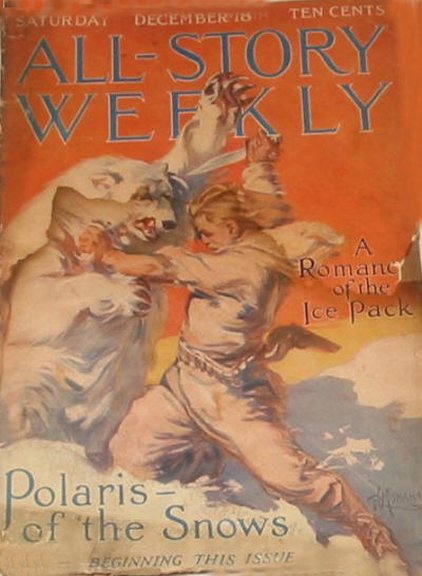

- Charles B. Stilson’s Polaris of the Snows (18 December 1915 – 1 January 1916 All-Story; in book form, 1965). Directly inspired by Edgar Rice Burroughs, and helped create the scientific romance trend. Features the Tarzan-like Polaris Janess, who spends his Antarctic childhood killing polar bears [polar bears live in the Arctic, but not Antarctica] and as an adult enjoys adventures in a Lost-World colony of Greeks and with technologically advanced survivors of Atlantis.

- Clotilde Graves’s “Lady Clanbevan’s Baby.” Immortality — involves radium. Sort of a fantasy parable, ends with a baby sporting a mustache. Collected in The Dreaming Sex.

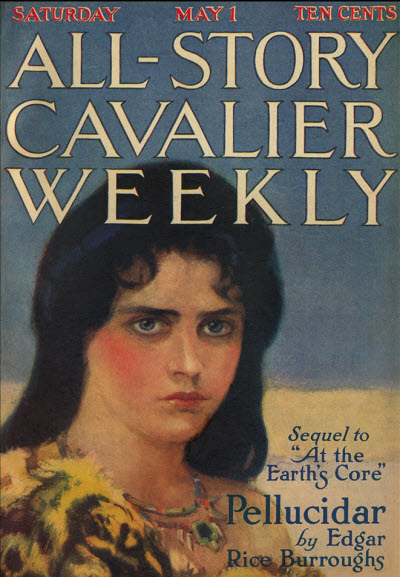

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Pellucidar. Burroughs’s third major series, the Pellucidar novels, based on the Hollow-Earth theory of John Cleves Symmes, began with At the Earth’s Core (All-Story Weekly, 1914) and continued in Pellucidar (All-Story Cavalier Weekly and All-Story Weekly, 1915). Pellucidar has been described as the best of Burroughs’s locales – a world without time where dinosaurs and beast-men roam circularly forever – and a perfect setting for bloodthirsty romantic adventure. Followed by Tanar of Pellucidar (Blue Book, 1929), Tarzan at the Earth’s Core (Blue Book, 1929–1930), Back to the Stone Age (as “Seven Worlds to Conquer,” Argosy, 1937), Land of Terror (1944), and Savage Pellucidar (stories February-April 1942 Amazing).

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s “Sweetheart Eternal.” A prehistoric adventure involving time travel. See 1914’s “The Eternal Lover.”

- George Allan England’s The Fatal Gift (4-25 September 1915 All-Story Weekly), a serial dealing with the production of an excessively beautiful superwoman by plastic surgery.

- George Allan England’s The Air Trust. Socialist thought, in the mode of Jack London, shapes the anticapitalist stances of The Air Trust (January-October 1915 The National Rip-Saw), which is centered on a cartel’s monopoly on oxygen.

- William Le Queux’s The Mystery of The Green Ray. On the eve of WWI, two friends go on a fishing holiday in Scotland before joining up. While staying at the house of retired General McLeod they become aware of mysterious apparitions on the loch. Matters turn more serious when Myra, the general’s daughter is struck blind at the same place as the apparitions were seen. The two set out to investigate the cause of the strange events, and what role, if any, the rich American has in the affair, as they try to solve.. the mystery of the green ray!

- George F. Stratton’s “Omegon” — series of boys’ adventures about a millionaire entrepreneur. Dime-novelish.

- Gerald Grogan’s A Drop in Infinity. The author served in World War One from as early as 1915; he was killed in 1918. The novel carries its unwilling protagonists Jack Thorpe and Marjorie Matthews via a mad scientist’s dimensional portal into an empty but congenial parallel world. There is some discussion of a potential multiverse of such worlds, each slightly different from the next, though the mad experimenter has found most of them dangerous and retained access only to two. In the place which the Adam-and-Eve protagonists call Marjorie-land a Robinsonade evolves, during which they become reconciled to their lot, are joined by further exiles from our world, have children, survive a crisis and find themselves finally isolated from Earth.

- Richard Dehan’s (Clotide Inez Mary Graves) “Lady Clanbevan’s Baby” in Off Sandy Hook, and other stories. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Eva Harrison’s Wireless Messages from Other Worlds. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Harry Stephen Keeler’s “John Jones’ Dollar” in Black Cat. Looks at the world of 3221 and how money invested in 1921 was now sufficient to buy the solar system, such was the power of compound interest. One of the last sf stories of note in this magazine, later reprinted in Gernsback’s Amazing.

- Luigi Pirandello’s Shoot: The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator. The protagonist ends by not knowing where his body ends and the machine he operates begins: “I cease to exist. It walks now, on my legs… I form part of its equipment.” Somewhere between metaphysics and proto-sf.

- Arthur Ransome’s The Elixir of Life. Gothic thriller of proto-sf interest set in Augustan England. The protagonist is a reclusive and feared philosopher who 200 years previously acquired the titular elixir of immortality from his late mentor. He discovers too late that the elixir has a corrupting influence on its possessor and that it only works at the expense of other people’s lives. Lovecraft praised this book, which bears many similarities to his own The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, written before Lovecraft discovered Ransome’s novel. “A very superior story of its kind …” – Locke, A Spectrum of Fantasy.

- Garrett P. Serviss’s The Moon Maiden. The novel originally appeared in Argosy; first published in book form in 1978. A dubiously complicated love tale involving lunar beings who have been guiding the earth (uplifting humankind) for millennia. Serviss’s last story.

- Otto Witt’s Hur månen erövrades (How the Moon Was Conquered). Jingoistic Swedish novel making it clear that the only people capable of such a feat are Swedes. A Swedish engineer constructs the first spaceship and after landing on the Moon is greeted by a chance phenomenon of lighting: “The snow was a deep blue, and its blue hue deepened further in the vicinity of the yellow light. The first thing to greet their arrival on the Moon was the blue and yellow Swedish flag.” His narrow morality, bland writing style, and nationalistic blindness make him at best a curiosity.

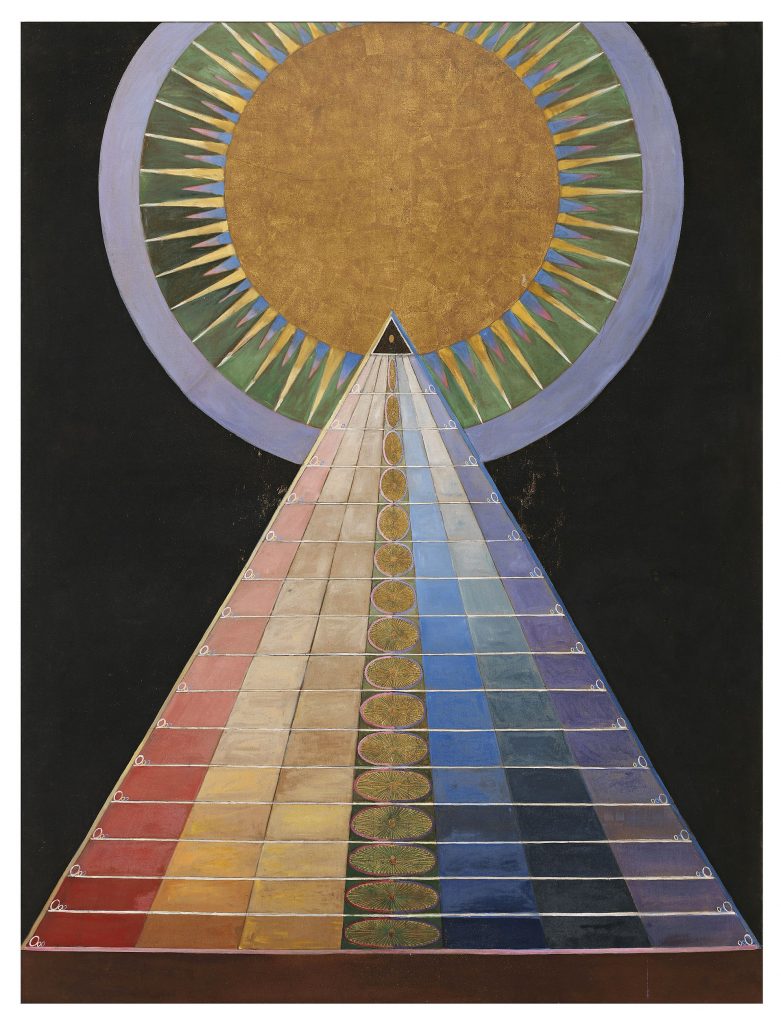

- Perley Poore Sheehan’s The Abyss of Wonders (January 1915 Argosy). Mixes Theosophy and superscience in its tale of a Lost Race in the Gobi Desert. The secret brotherhood of the Sons of the Blue Wolf seeks a hidden theosophical civilization deep in the Gobi Desert, and a dull middle-class US American teen discovers within himself the secrets of Siberian shamanism and an Ocarina of Time (“Throughout the ages it had kept its mellow flute-tone.”) Somewhat tepidly received by genre critics of the future-hungry 1950s, Sheehan’s wide-eyed wonder and “imprecise” (Bleiler) worldbuilding may have considerably more appeal to a broad-minded modern readership unconcerned with rigid genre boundaries and unbothered by mystical enthusiasms.

- Vladimir Obruchev’s Плутония (Plutoniya). Obruchev, a Russian and Soviet geologist who specialized in the study of Siberia and Central Asia. His Plutoniya (translated as Plutonia, 1957) is a hollow-earth story: Dinosaurs and other Jurassic species are found in a fictional underground area north of Alaska. The descriptive passages are made more credible by Obruchev’s extensive knowledge of paleontology.

- Perley Poore Sheehan’s Judith of Babylon. A five-part novel. Part one appeared in All-Story Cavalier Weekly, February 6, 1915. (Not sure if the other parts were ever published?) Remarkable anticipation of the use of propaganda to gain control of the masses. Mentioned in Moskowitz’s Scientific Romances.

- George Allen England’s “The Tenth Question” (18 December 1915 All-Story Weekly), a mathematical puzzle story. It was later rewritten by and credited to Stanley G Weinbaum as “The Brink of Infinity” (December 1936 Thrilling Wonder).

- Allen Upward’s Paradise Found: Or, the Superman Found Out: a Joke at Everybody’s Expense in Three Acts (1914 [technically unpublished]; 1915 in published form) as by Saint George. A sleeper-awakes play set two centuries hence featuring George Bernard Shaw, awoken from slumber and finding the new world, a utopia constructed on Shavian lines, to be intolerable.

- Muriel Pollexfen’s “Monsieur Fly-by-Night.” A Ruritanian romance with a flying machine. Collected in The Dreaming Sex. Fun fact: Pollexfen was related to W.B. Yeats.

ALSO: Einstein postulates his General Theory of Relativity. Haldane’s paper “Reduplication in mice” is the first demonstration of genetic linkage in mammals; it has been called the most important science article ever written in a front-line trench. Robert Innes discovers Proxima Centauri, the closest star to Earth after the Sun. Thomas Hunt Morgan, demonstrates non-inherited genetic mutation, undermining the conceptual basis of eugenics. Junkers builds the first fighter plane. First transcontinental telephone call. The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the predecessor of NASA, is established in the United States. WWI raging — first German submarine attacks, Germans sink Lusitania, first Zeppelin attack on London, etc. (“The war is based on a crass error,” Hugo Ball wrote in his diary on June 26, 1915. “Men have been mistaken for machines.”) Brooks’ America’s Coming of Age, Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps, Lawrence’s The Rainbow, Pound’s Cathay, Burnett’s The Lost Prince, Sabatini’s The Sea Hawk. Duchamp’s first Dada-style paintings. D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. Margaret Sanger jailed for writing first book on birth control.

Gurdjieff accepts the Russian esotericist P.D. Ouspensky (who’d become interested in Theosophy in 1907) as a pupil in 1915. Ouspensky would study under Gurdjieff from 1915 to 1924.

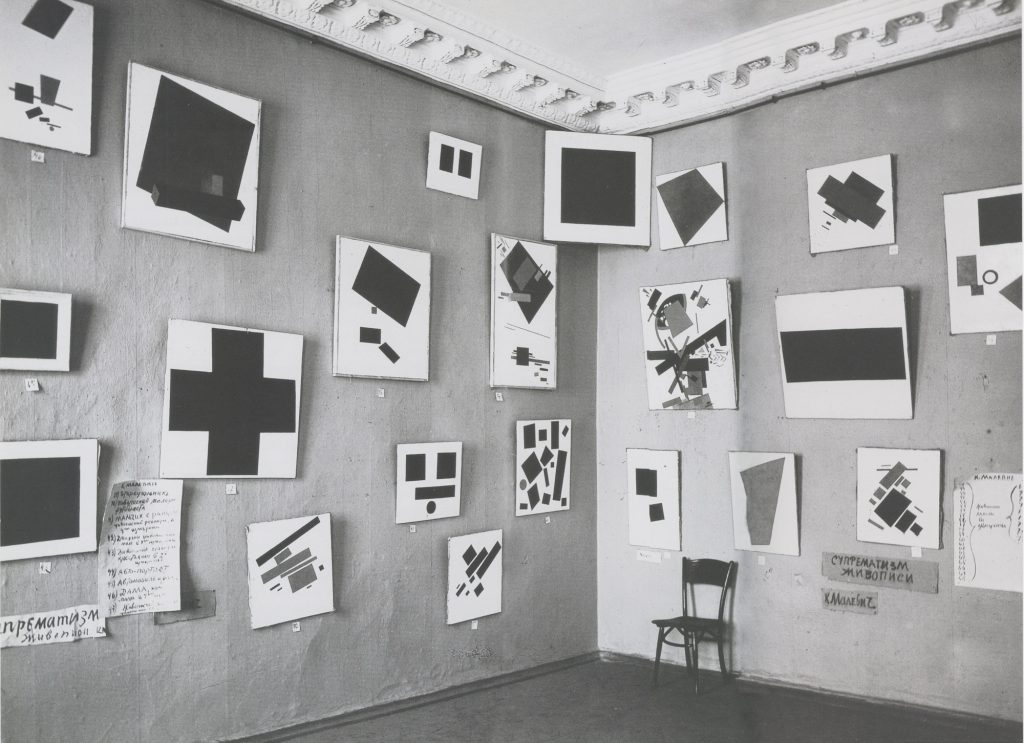

Kasimir Malevich’s works in The Last Futurist Exhibition are geometric abstractions, although some of them have titles that suggest real-world references, such as Airplane Flying. Malevich wrote a theoretical justification of non-representational “Suprematist” painting the same year. Several of the titles to Malevich’s paintings in 1915 express the concept of a non-Euclidean geometry which imagined forms in movement, or through time; titles such as: Pictorial Masses in Two Dimensions in a State of Rest. Suprematist works were intended to represent the concept of a body passing from three-dimensional space into the fourth dimension; there was a reveloutionary political analog — the idea of tearing down a constrictive social order in the name of liberty.

During 1915, Charles Fort began to write two books, titled X and Y, the first dealing with the idea that beings on Mars were controlling events on Earth, and the second with the postulation of a sinister civilization extant at the South Pole. These books caught the attention of Theodore Dreiser, who tried to get them published, but to no avail. Discouraged, Fort burnt the manuscripts, but soon began work on the book that would change the course of his life, The Book of the Damned (1919).

Abstract Composition is a painting by the British artist Jessica Dismorr. It features a series of pastel-coloured geometric forms, reminiscent of architectural components, overlapping on a black ground. A dark yellow triangular prism with a curved side provides a vertical focus and splits the composition in two. A smaller pale pink object appears to approach the foreground, which is crowded by five more objects of different shapes and colors.

Around the time that she created Abstract Composition, Dismorr contributed six pieces of writing titled ‘Poems and Notes’ and two illustrations, Design and The Engine, to the second and final issue of Blast, a modernist magazine published by the Vorticist movement, of which Dismorr was a signatory member.

Sharp diagonal lines converge towards a focal point. This painting recalls the poet Ezra Pound’s description of the vortex as ‘absorbing all that is around it in a violent whirling’. The vorticist group’s aggressive rhetoric, angular style and focus on the energy of modern life were similar to Italian futurism. However, they did not share the futurists’ emphasis on speed, or their romanticisation of technology. Wadsworth and the other vorticists had a more matter-of-fact attitude to the machine age. Their images betray little sense of celebratory excitement.

Images of hands and facial features are hidden within this jagged composition. There is an eye, a nose and a mouth. The fragmented figure seems to be mounted on a diagonally thrusting rocket. The fusion of man and machine was a common theme for the vorticists. However, many became increasingly disillusioned with the supposed dynamism of the machine age in the face of the mechanised killing during the First World War.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin