RADIUM AGE: 1914

By:

July 24, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

The year 1914, in my periodization scheme, marks the beginning of the cultural decade known as the “Nineteen-Teens.” Of course there are no hard stops and starts in culture, so it’s more accurate to describe 1914 (and 1913) as cusp years during which the Aughts end and the Teens begin.

The Teens would be characterized by an exponential expansion of mechanized industrialization, fueled by newly abstract modes of finance.

The All-Story Magazine, founded in 1905, became All-Story Weekly in 1914. It absorbed The Cavalier, another Munsey title, later that year, publishing as All-Story Cavalier Weekly for a year afer that before reverting to All-Story Weekly. It ran until 1920, when it was absorbed by the Argosy, which then published as Argosy All-Story Weekly for some years.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1914.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1914, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: ATOMIC ENGINE | TIME TRAVEL (n.) | WELLSIAN.

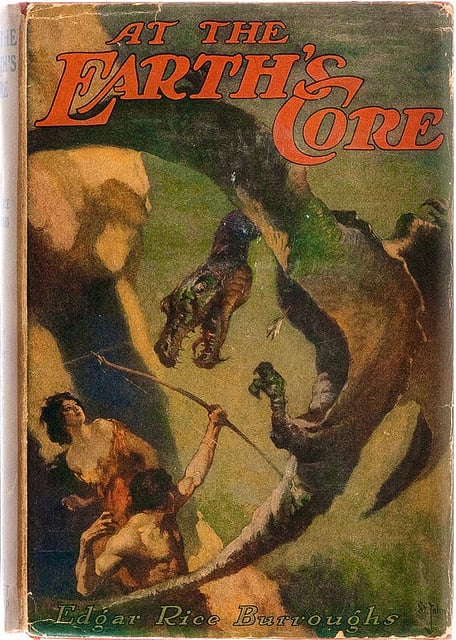

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s At the Earth’s Core (1914). Thanks to his futuristic “iron mole” machine, mining engineer David Innes discovers that the Earth is hollow. At the planet’s center is Pellucidar, a land — lit by a miniature Sun — in which stone-age humans are dominated by the Mahars, flying reptiles who are highly intelligent and evolved. Innes must battle prehistoric creatures and proto-humanoids, rescue the lovely Dian, and lead a revolt against the Mahars. Oh — and somehow return to the surface of the planet. The first of seven Pellucidar novels. Fun fact: H.P. Lovecraft was a fan; check out his 1931 adventure At the Mountains of Madness. It’s also worth mentioning that Burroughs’s Tarzan character eventually visits Pellucidar.

- Inez Haynes Irwin’s Angel Island (1914). Shipwrecked on an uncharted island, five men encounter five winged women, rebels from their tribe who’ve decided to fly south instead of north. Frustrated by how aloof and skittish the women are, the men clip the women’s wings. At first, four of the five women enjoy the attention — all but one, their leader, Julia — and marry four of the men. However, the domesticated women soon realize that married life is a form of servitude, and they lament their lost freedom. When they bear children (mostly wingless boys) and discover that the one winged girl-child will also have her wings clipped, the domesticated women take a stand. They demand rights for women — after which things change on the island. The women’s wings are no longer clipped. Julia gets married: symbolically, her child is a winged boy. Fun fact: Inez Haynes Irwin, who’d been active in the suffragist movement, was fiction editor of the left-wing periodical The Masses.

- H.G. Wells’s The World Set Free (1914). Building on the recent discovery that “the atom, that once we thought hard and impenetrable, and indivisible and final and — lifeless — lifeless, is really a reservoir of immense energy,” Wells conjures a 1950s England in which clean, efficient atomic engines have transformed life for the better. Alas, a world war breaks out, in which atomic bombs wipe out the world’s great cities. Worldwide civilization is on the brink of collapse, when a conference of enlightened monarchs, presidents, powerful journalists, and scientists gathers in order to establish a peaceful one-world order. When one Kissinger-like figure begins to strategize about maintaining national autonomy and monarchical authority within this utopian world government, another character shuts him up with one word: “BANG!” Fun fact: The astrophysicist Leó Szilárd, who worked on the Manhattan Project, claimed that The World Set Free helped him conceive of the nuclear chain reaction. See my essay on The World Set Free and Wells’s two books of floor games for children. MIT Press’s Radium Age series reissued this title in 2022.

- Raymond Roussel’s Locus Solus (1914). Invited to Locus Solus, the suburban estate of the reclusive, fabulously wealthy French scientist Martial Canterel, a group of his colleagues are introduced to strange and complex inventions and oddities: a wind-powered paving bot, which constructs elaborate mosaics of human teeth; the preserved head of 18th-century revolutionary Danton, which speaks when stimulated by a hairless cat; a vast aquarium in whose “aqua-mican” terrestrial mammals can breathe (hm — a similar appratus had appeared in Gustave Le Rouge’s 1909 sci-fi adventure La Guerre des Vampires); a doctor who painlessly removes fingernails and replaces them with mirrors; and so forth. Within an enormous glass cage, eight zombies whom Canterel has revived (thanks to his invention, “resurrectine”) act out the most important incidents of their lives — over and over again, sometimes in the company of their still-living family members! Behind some of Canterel’s artifacts lie strange and disturbing stories (and stories within stories); behind others, delightfully surreal ones. We’re also treated to sober explications of the technology making each exhibit possible. It’s a far-out, macabre wunderkammer, and a philosophical novel exploring what Adorno and Horkheimer would later call the dialectic of Enlightenment — i.e., the irrationality of science, the logic of obsession. Fun fact: Roussel composed Locus Solus using eccentric, punning guiding principles — explained in his posthumous text, How I Wrote Certain of My Books (1935) — that would influence later experimentalists. John Ashbery, Harry Mathews, James Schuyler, and Kenneth Koch edited a 1960s journal called Locus Solus (after Roussel’s novel), which has been called the New York School of poets’ manifesto.

- George Allen England’s The Empire in the Air (14 November-5 December 1914 All-Story Cavalier Weekly; didn’t appear in book form until 2006), a serialized novel of invasion by immaterial beings from the fourth dimension, who establish a Pax Aeronautica. Moskowitz’s History of Scientific Romance says it’s a super-science epic 15 years ahead of its time and under-appreciated.

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s novella Danger! (in The Strand); assembled in Danger!, and Other Stories (1918). Doyle’s contribution to the Future War genre, anticipating submarine attacks on shipping.

- G.K. Chesterton’s The Flying Inn (1914). When a British politician, Lord Ivywood, sets out to Islamize Great Britain — so that he can enjoy the benefits of polygamy — he cleverly enlists the assistance of the nation’s “smart set,” who are all too eager to embrace trendy, “Eastern” fads like Islam. Among other changes, Ivywood pushes through laws requiring that alcohol only be sold by an inn displaying a sign… and banning inn signs. Patrick Dalroy, a hard-drinking Irishman, and Humphrey Pump, dispossessed landlord of one of the shuttered English inns, take to roaming the countryside with a cart (later, a motorcar) full of rum. Meanwhile, we discover that Ivywood is a pseudo-Nietzschean figure bent on destroying Christianity and Western culture… and that he is smuggling a Turkish army into England! Fun fact: According to some critics, Chesterton makes this book’s reader complicit in an architecture of unquestioned privilege and received prejudice.

- J.U. Giesy’s All for His Country (21 February-14 March in Cavalier; as a book, 1915). A Yellow Peril story combining Future War and Edisonade elements. It pits a young inventor’s radium-powered antigravity plane against the treacherous Japanese, who burn Los Angeles to the ground… and who boast their own advanced weapon. Ominously, as the SFE points out, Giesy also accuses Japanese-Americans from California of betrayal.

- Henri Barbot’s Paris en feu! (Ignis ardens), a mixture of proto-sf and Catholic mysticism, predicts a war — with Germany — of zeppelins and radio waves. There’s a coup led by freemasons, France’s churches are converted into pornographic theaters, and a burst of Hertzian waves from the Eiffel tower with atomic bomb-like consequences. The author’s first novel. See Hervé G. Picherit’s essay “A War of Sensibilities: Recovering Henri Barbot’s Paris en feu (Ignis ardens).”

- William Hope Hodgson’s “The Stone Ship” (1 July 1914 in Red Magazine as “The Mystery of the Ship in the Night”; expanded in the 1916 collection The Luck of the Strong. An ancient wreck is raised to the surface by a volcanic eruption, bringing many weird creatures with it. SF?

- Algernon Blackwood’s “A Victim of Higher Space.” A John Silence occult-detective story. See 1908 for more info on this series. It was serialized at HILOBROW in 2022. Will be reissued by MIT Press as part of the collection More Voices from the Radium Age.

- Frederic Carrel’s 2010. Among the many inventions by Caesar Brent, a superheroic “universal” and president of the Council of Federated States (England and Europe), is a process to turn Negro skin white. A British fifth column, the League of Good (which includes “universals” opposing Brent), allied with Orientals who plan to conquer Europe, threaten the Anglo-European Federation. The League spreads a new disease which sickens and kills the universals, one of whom is Brent’s young son. Silvanus Strong, leader of the grateful (yeesh) whitened Negroes, makes plans to attack the Asians. Meanwhile, England is invaded by a flotilla of giant airships, piloted by Amazonian Asian women, that devastates the country. Ultimately, Brent’s daughter poisons all the Asian women. Apparently a parody of Wells, not to mention of M.P. Shiel’s bloodthirsty future war stories.

- Arthur Cheney Train’s The Man who Rocked the Earth. Originally serialized in the Saturday Evening Post. The near future course of WWI is interrupted by messages from a mysterious PAX threatening super scientific punishments if war is not stopped. After some demonstrations, featuring rays, a flying ship, atomic energy, and the slowing of Earth’s orbit, which causes vast earthquakes, the nations obey. Alas, PAX becomes a mad scientist, but dies before he can turn Europe into an Arctic wilderness. Possibly the first use of radium sickness in proto-sf. “Unusual in early science-fiction in paying heed to correct science. Many of Wood’s scientific details are still valid, although the extrapolations from them are, of course, fantastic.” – Bleiler. The author is best known for work outside the sf field, particularly his legal series about the lawyer Ephraim Tutt. See 1916 for info on the story’s sequel.

- Paul Scheerbart’s The Gray Cloth with Ten Percent White: A Ladies’ Novel is an avant-garde novel by the fantasist and visionary German writer Paul Scheerbart. Set in the near future, it features an architect who travels the world in his airship, creating luminescent glass constructions everywhere: concert halls, elevated trains, airy keeps for retired pilots. He requires his wife to wear mostly grey clothing, in order not to compete with his polychromatic dream. “The oneiric fluency of the tale, and the Expressionist yearnings Scheerbart gives habitation to in the structures he imagines for this narrative, powerfully evoke the lure of the future in the years before World War One,” notes the SFE. During this period Scheerbart was well-known for his modernist advocacy of “glass architecture”, in essays and fictions, most notably perhaps in the nonfiction Glasarchitektur (1914). The author may be best known for 1913’s Lesabéndio: Ein Asteroiden-Roman.

- Coutts Brisbane’s “A By-Product.” Mining the sea for gold produces giant crabs.

- Coutts Brisbane’s “De Profundis.” Giant ants.

- Lillian and George Randolph Chester’s The Ball of Fire. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Bertha von Suttner’s When Thoughts Will Soar: A Romance of the Immediate Future. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s “The Eternal Lover.” A prehistoric adventure involving time travel featuring a character, Barney Custer, who reappears in the author’s Ruritanian The Mad King.

- J. Brant’s “Equality Isle.” Mentioned in Moskowitz’s When Women Rule. Suffragettes on an island. Is it sf?

- M.P. Shiel’s “The Place of Pain.” A natural water lens that shows horrors on the Moon. Moskowitz calls it one of Shiel’s most effective short pieces. When it was collected with other pieces in a 1935 book it was retitled “The Place of Pain Day” — it was anthologized in several horror collections. Is it sf? Or is the character Podd, who says he saw horrors on the moon through, just crazy?

- Percy Atkinson’s “Votes For Men.” Mentioned in Moskowitz’s When Women Rule. Amusing story set in 1923, in which men don’t have the right to say no to marriage.

WWI: Franz Ferdinand assassinated, triggering a train of military presumptions and defensive alliances in semiautomatic way that seemed to exclude considerations of prudence, moral purpose, or even national interest. Vast numbers of technological innovations would emerge from WWI — e.g., the wristwatch, the steel helmet, poison gas, the semiautomatic rifle, aerial surveillance photography, submarines, the use of Zeppelins and airplanes for military purposes. The futile slaughter during the five-month siege at the Somme River (among other battles) marked the demise of an older aesthetic and ethical code of heroism and courage. For many intellectuals, WWI produced a collapse of confidence in the rhetoric of the culture of rationality that had prevailed in Europe since the Enlightenment.

ALSO: J.H. Jeans’ “Radiation and the Quantum Theory.” American engineer, professor, physicist, and inventor Robert Goddard makes his first experiments with rocketry; in 1926, he would be the first to launch a liquid-fueled rocket. Manning’s Geometry of Four Dimensions. To support France’s war effort, Marie Curie develops mobile radiography units, which came to be popularly known as petites Curies; she became the director of the Red Cross Radiology Service and directed the installation of 200 radiological units at Allied field hospitals. Panama Canal opened. Shackleton embarks on Antarctic expedition. The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act requires cocaine and narcotics (in the US) to be dispensed only with a doctor’s order. Joyce’s Dubliners, Frost’s North of Boston. Gide’s Les caves du Vatican (the idea of the geste gratuit was immediately adopted from this novel by the Dadaists), Conan Doyle‘s Sherlock Holmes adventure The Valley of Fear, Rhodes’ Western adventure Bransford in Arcadia. Charlie Chaplin arrives in Los Angeles and begins working for Keystone.

Arthur Jerome Eddy, writing about abstract art in 1914, describes the goal as a “pure art” which “speaks from soul to soul, it is not dependent upon one’s use of objective and imitative forms.” Art as telepathic communication, a means of creatine sympathetic vibrations in the viewer. When abstract forms and colors are used to communicate a spiritual content — see Besant and Leadbeater’s Thought Forms — “the world reverberates.”

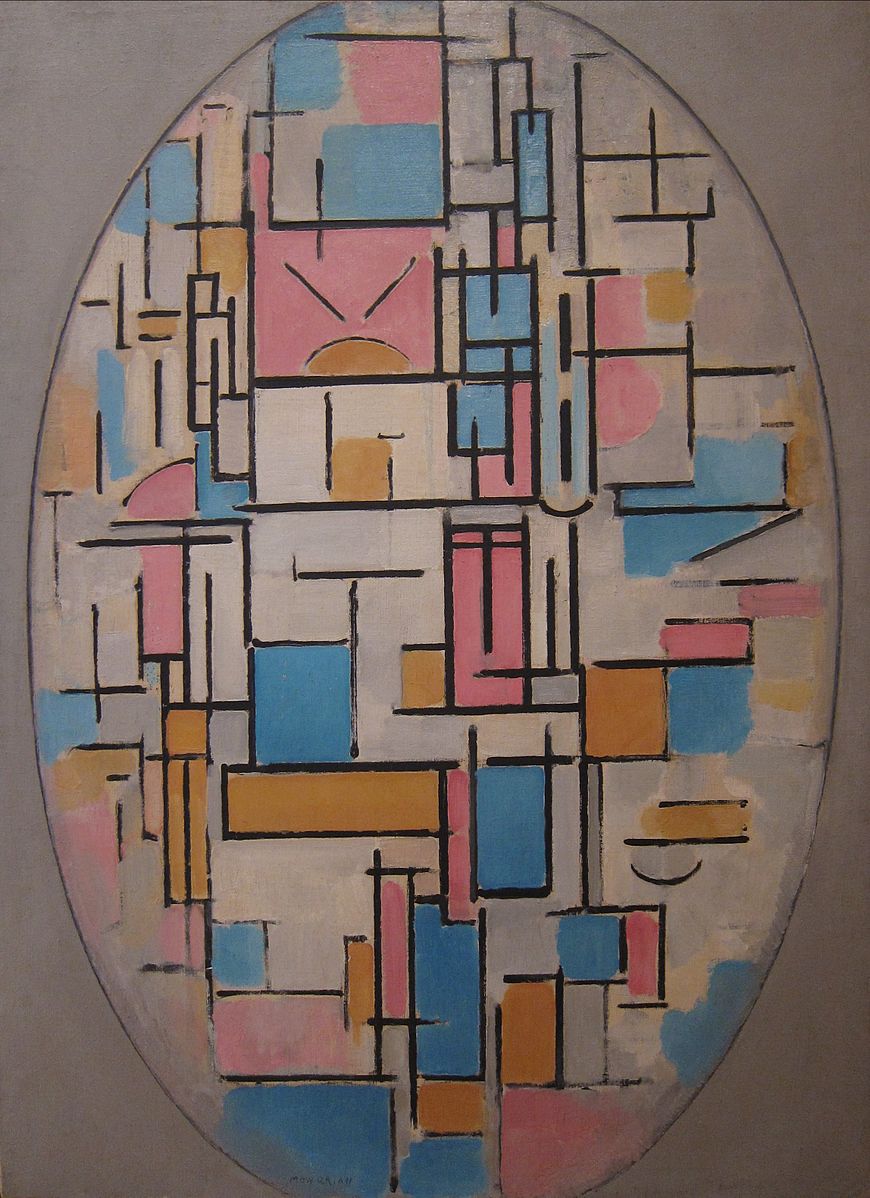

Mondrian moved to Paris in 1911/1912; his work became more Cubist but it deviated from orthodox Cubism in its theosophy-driven thinking about line and color. Radically reducing lines to horizontal and vertical, radically reducing color to the three primary colors… he was essentially painting semiotic charts of a unity that would resolve harmoniously all antitheses.

Note on Vorticism.

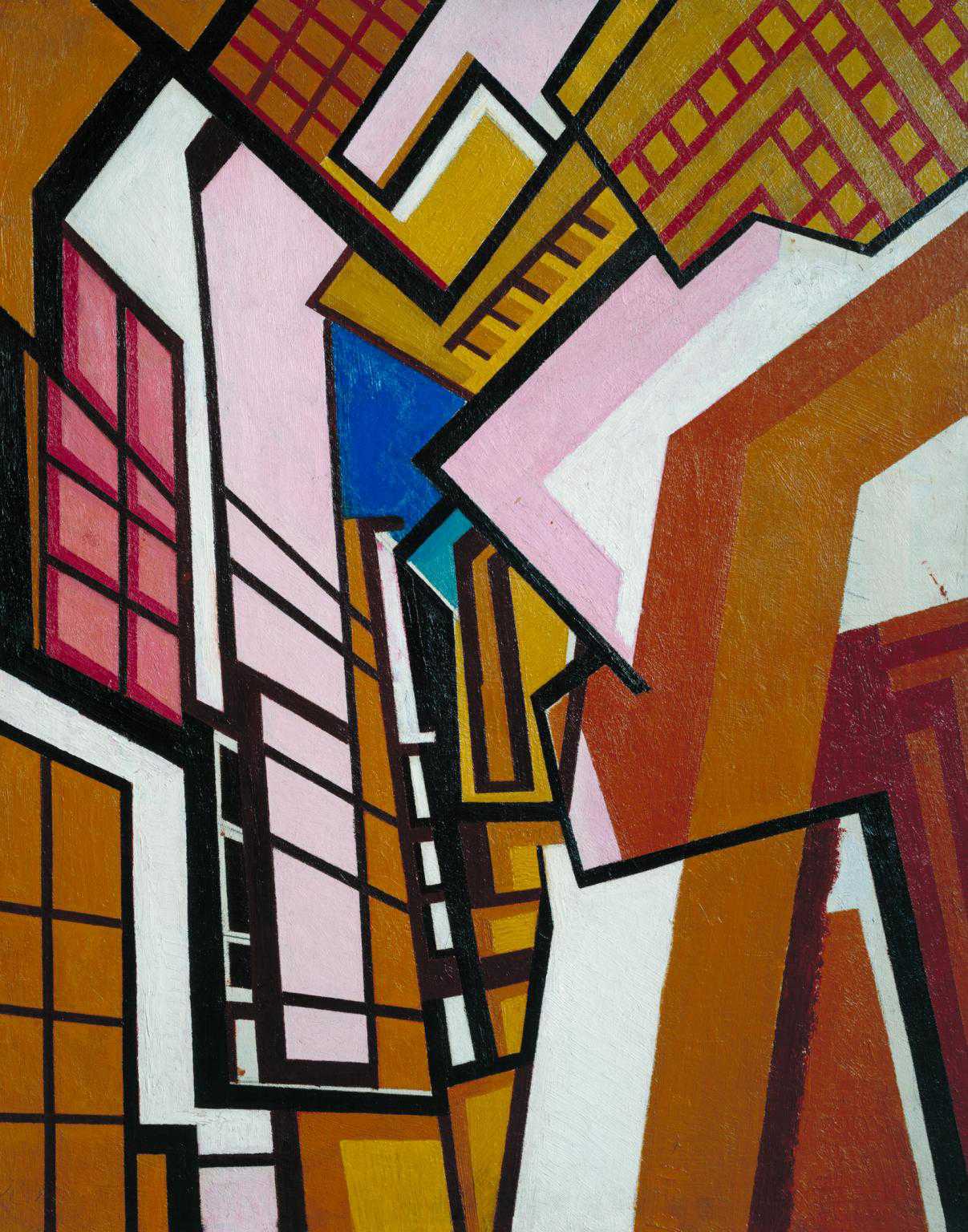

The vorticists were a British avant-garde group formed in London in 1914 with the aim of creating art that expressed the dynamism of the modern world.

Around 1914, Ezra Pound began to criticize his fellow Imagistes for their sloppiness with regard to le mot juste, thus turning Imagism into a mere passive Impressionism, and vers libre into a rather updated version of verbose Victorianism, making it synonymous with any kind of unrhymed, irregular verse. Pound left the Imagist movement for that of the more stricter and more intense Vorticism, which was engineered in 1914 by Wyndham Lewis. This avant-garde movement experimented with forms and geometric abstractions in an attempt to bridge the differences between literature and the visual arts without actually fusing them. Pound’s article “Vorticism” in the Fortnightly Review of September 1914 became the movement’s aesthetic manifesto. In the visual arts it was to be presented as a sharply defined form with distinct and geometrical lines and shapes as the expression of energy or emotion, while the medium for poetry was still the Image. Yet it was not exactly the same Image as used by the Imagists, as it now not only had to express the virtù of an object but also its very energy.

–> see Ezra Pound and Neoplatonism (2004) y P. Th. M. G. Liebregts.

Vorticist painting combined cubist fragmentation of reality with hard-edged imagery derived from the machine and the urban environment. It was, in effect, a British equivalent to futurism, although with doctrinal differences, and Lewis was deeply hostile to the futurists. Other artists involved with the group were Lawrence Atkinson, Jessica Dismorr, Cuthbert Hamilton, William Roberts, Helen Saunders, Edward Wadsworth, and the sculptors Sir Jacob Epstein and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska.

The First World War brought vorticism to an end, although in 1920 Lewis made a brief attempt to revive it with Group X.

Gino Severini’s Spherical Expansion of Light (Centripetal and Centrifugal) (c. 1914) influenced by his fascination with spiritualism — a fascination he shared with other Italian Futurists.

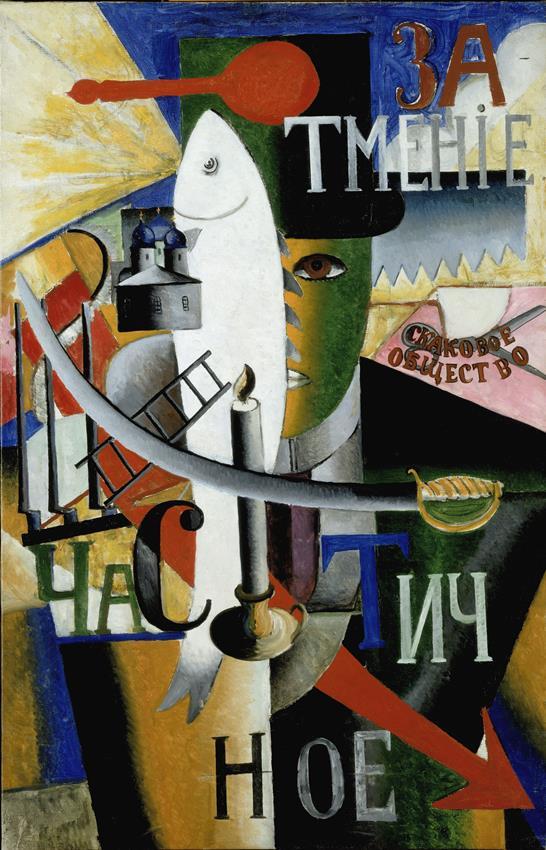

In 1914 Malevich turned to a new style of painting but with the same purpose (as his “zaum realism”) in mind. His Alogist pictures, such as An Englishman in Moscow (1913–1914) project a dense collection of whole and partial images, words, collage elements, objects fastened to the canvas, and puzzling titles. They replace the structural “higher geometries” of Cubism with the secret logic of content devised by the artist.

Malevich may have solved the problem of giving a visual image to “zaum” through reading descriptions by Hinton and Ouspensky of the geometric cross-sections produced by a cube falling through a plane.

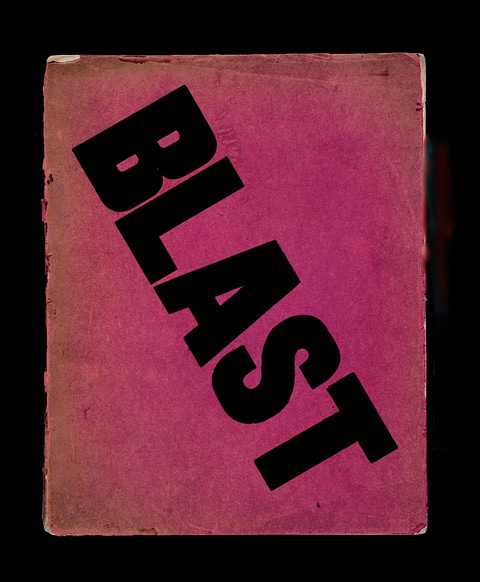

Possibly the best known item that the Vorticists produced is their journal BLAST, in June 1914 just before the beginning of the First World War.

Edited by Wyndham Lewis, its radical intention was immediately evident when it first appeared. It has an extraordinarily bright pink colour with the title BLAST written across the cover in huge, bold, black letters. Ezra Pound described it as this “great MAGENTA cover’d opusculus”. The first section of the journal starts with a sequence of twenty-odd pages which are presented like a manifesto. Each page has a dramatic piece of graphic design, in which the editors ‘Blast’ and ‘Bless’ different things – often these are the same things. It is sardonic and humorous to read, but has a great vitriolic tone as well.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin