RADIUM AGE: 1910

By:

June 24, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

In late 1910 the Ridgway Company, which published the highly influential slick Everybody’s, launched Adventure. (One of its earliest serials was John Buchan’s Prester John.) A major publisher of writers such as Talbot Mundy and Harold Lamb, it soon became regarded as the leading pulp magazine.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1910.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1910, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: none!

- Algernon Blackwood’s The Human Chord — occult proto-sf dedicated “to those who hear.” Blackwood’s yarn takes the Kabbalah as its theme. An imaginative young British man, Robert Spinrobin, answers a want ad for “Secretarial Assistant with courage and imagination. Tenor voice and some knowledge of Hebrew essential; single; unworldly.” He soon discovers that his new employer, the retired Rev. Skale, is conducting a sound experiment in a remote Welsh location. Skale’s pseudo-scientific take on the ancient mystical notion that “everything in nature has a true name, and he who has the power to call a thing by its proper name can make it subservient to his will” has something to do with vibrations. Learning to call a thing by its true name is an empirical process of experimentation. Alas, Skale succeeds all too well in his experiment… and his success may threaten the world!

- Mary Hunter Austin’s Outland. One of the early nature writers of the American Southwest, Austin’s classic The Land of Little Rain (1903) describes the fauna, flora, and people – as well as evoking the mysticism and spirituality – of the region between the High Sierra and the Mojave Desert of southern California. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Maurice Renard’s The Blue Peril. Having discovered a planet swaddled in an impenetrable etheric “ocean,” the Sarvants — an advanced race of space explorers — fish for specimens of its two- and four-legged indigenous life-forms. Like scientists of any species, they dissect their specimens and toss the remains back into the ocean. Having studied and classified these exotic creatures, which are presumably incapable of either suffering or rational thought, the Sarvants preserve and mount a few remaining examples for display. Meanwhile, in eastern France, human body parts are discovered — scattered across the landscape. An investigation is mounted; who is committing these crimes? In the pocket of one of the victims, a written account is discovered: Aliens, it seems, are abducting Earth creatures! The French authorities manage to communicate with the aliens — the Sarvants — who turn out to be tiny insectile creatures capable of assembling and dissembling their bodies with one another at will, in order to form such organs as are necessary for controlling their technology. Astonished to realized that Earth creatures are intelligent (though bizarrely shaped), the Sarvants cease their experiments. Could this novel have been the inspiration (by way of Charles Fort) of other such Earth-unknowingly-occupied-by-superior-aliens sf stories like Eric Frank Russell’s Sinister Barrier (1939)?

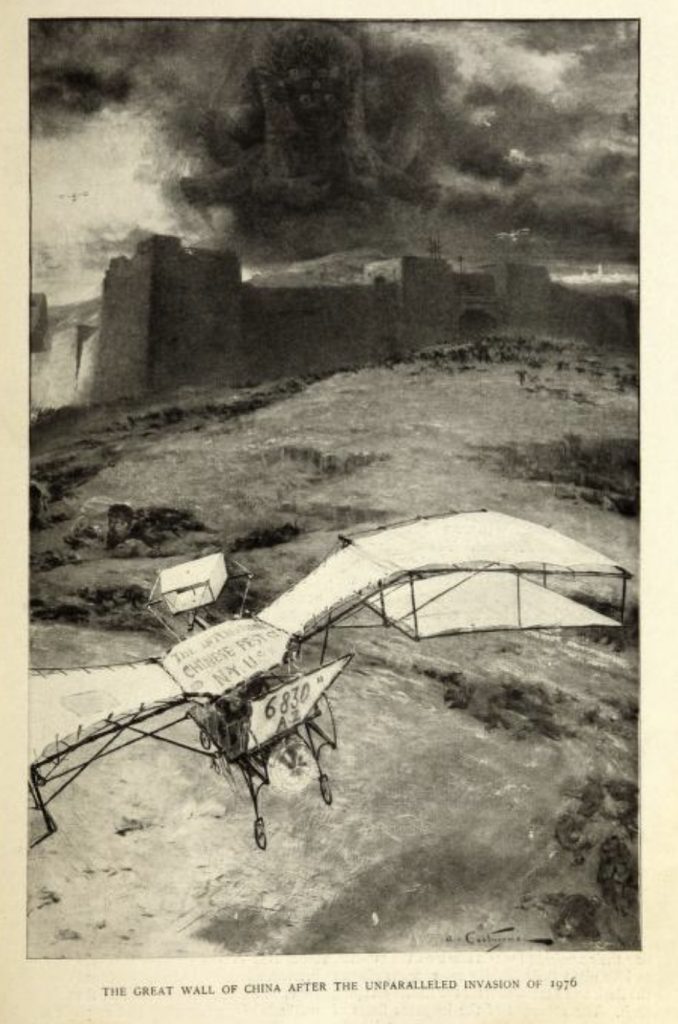

- Jack London’s “The Unparalleled Invasion” (July 1910 McClure’s), a Yellow Peril tale which London himself described as “an interesting pseudo-scientific yarn.” In the late twentieth century, after Chinese population growth and the Chinese work ethic has threatened the rest of the world, the White nations commit genocide through an aerial germ-warfare assault [shown in illo above], and fill an emptied China with White settlers; thanks to this final solution, an epoch of “splendid mechanical, intellectual, and art output” can now begin. The story gives expression to the era’s premonition of the precariousness of white racial supremacy, and also pays homage to an emergent science and scientism — specifically, around the discourse of genetics [see below], which revitalized 19th-century eugenic thinking, and which hailed the scientist/geneticist as defender of social health and racial culture — that made racial anxieties both more frightening and more manageable. (See John N. Swift’s 2002 essay “Jack London’s ‘The Unparalleled Invasion’: Germ Warfare, Eugenics, and Cultural Hygiene.”) Scholars argue over whether London was racist; racist aspects of his fiction, some claim, is so extravagantly caricatured and riddled with tonal ironies that it may in fact be dark Swiftean satire. However, the premise, themes, and even some passages of “The Unparalleled Invasion” were borrowed from London’s 1904 “Yellow Peril” essay, where he warns that “the menace to the Western World lies, not in the [Japanese] little brown man, but in the four hundred millions of [Chinese] yellow men.” And London was a proponent of eugenics. So… yes, he seems racist! See 1900 for more info on the Yellow Peril meme of this era.

- Katharine Fay Dewey’s Star People. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- R.O. Eastman’s “The Phonographic Apartment” (Blue Book) sort of predicts Artificial Intelligence (run amuck). Johnson’s friend has invented and set up an automated living facility. Lights go on and off, suitable music is played, doors open and close, all automatically. Johnson is driven to distraction by the officious equipment, which eventually goes haywire.

- Arthur B. Reeve’s The Silent Bullet story collection. Craig Kennedy — a fictional sleuth who has been called America’s Sherlock Holmes — is a scientist detective at Columbia University. He uses his knowledge of chemistry and psychoanalysis to solve cases, and uses exotic devices in his work such as lie detectors, gyroscopes, and portable seismographs. (So — not exactly sf, then.) He first appeared in the December 1910 issue of Cosmopolitan, in “The Case of Helen Bond.” He returned for many short stories and 26 novels. Fun fact: The character’s name was spoofed in 1916 by Douglas Fairbanks, who played “Coke Enneday” in the cocaine comedy film and Sherlock Holmes sendup The Mystery of the Leaping Fish.

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Terror of Blue John Gap” — surviving dinosaur.

- Edith Nesbit’s The Magic City. The young protagonist creates an ideal city on his table top and then enters it , becoming its savior. Fantasy, really — see Edward Eager’s excellent update of this idea in Knight’s Castle (1956). But utopian, too….

- Garret Smith’s “On the Brink of 2000” — January 1910 Argosy — which features a device to see anything happening anywhere in the world. (The SFE says: “Smith was a sometimes capable writer whose ideas tended to outclass his fiction.”)

- Hillaire Belloc’s Pongo and the Bull. The final volume of a trilogy; this one extends his satire of UK politics into the 1920s.

- Iwan T Aminoff’s Invasionen (The Invasion). Republished 1914 as Det eröfrade landet (The Conquered Land), pictured above. Set in an already conquered Sweden. He’d also write invasion stories about Norway and Finland. One of the first Swedish proto-sf authors; he wrote as Radscha.

- J.H. Rosny ainé’s La Mort de la Terre. Rosny aîné was the pseudonym of Joseph Henri Honoré Boex, a French author of Belgian origin who is considered one of the founding figures of proto-sf. (He wrote many far-out scientific romances, including 1895’s “Un Autre Monde,” in which only a mutant can detect Earth’s invisible coinhabitants.) This novella takes place in the far future, when the last descendants of mankind become aware of the emergence of a new species, the metal-based “Ferromagnetals,” who will replace us now that the Earth has become an immense, dry desert. (Rosny “excised the anthropomorphic from science fiction,” I’ve read somewhere.) Rosny’s vision of global environmental crisis is prescient. An imbalance created partly by humans turns Earth to desert. Targ, the last man, succumbs with Darwinian altruism. Realizing that carbon-based life must perish so that the iron-based Ferromagnetics can inhabit the stricken planet, he invites them to take his blood. Fun fact: the survivors stay in touch via the “Great Planetary” communications web. The narrative focuses mainly on group led by Targ, who at the beginning of the story is the “watchman” (“veilleur”) of the Great Planetary.

- C.J. Cutcliffe Hyne’s Empire of the World (May 1909-April 1910 The London Magazine; 1910; vt Emperor of the World: A Tale of an Anglo-American War 1915), where a disintegrator ray is used in a typical Scientific Romance climax to enforce world peace.

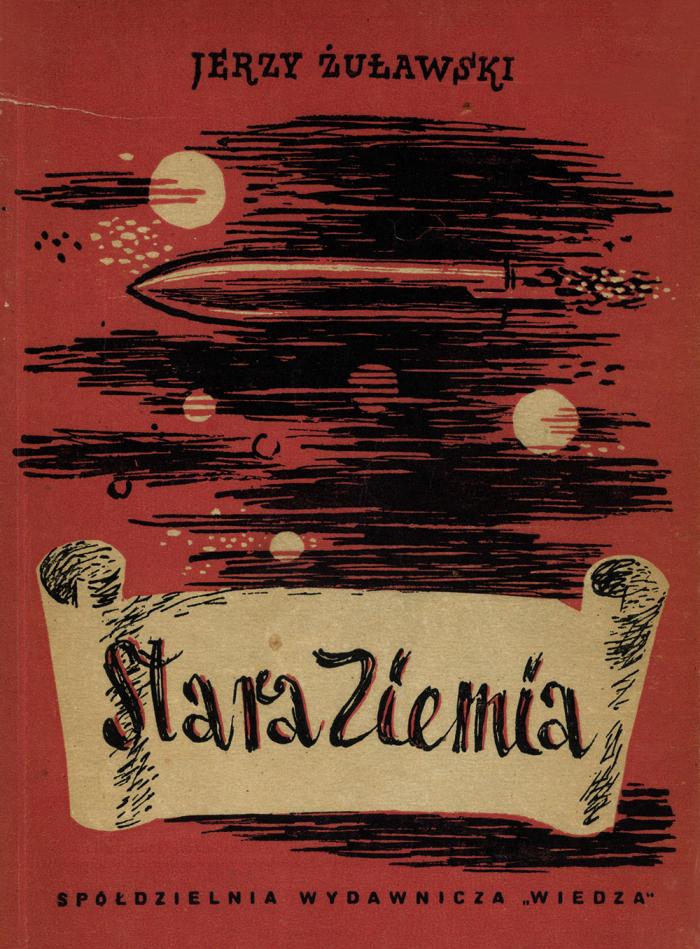

- Jerzy Żuławski’s Stara Ziemia (The Old Earth). The first installments of the final volume in Żuławski’s series. Two of the diminutive human denizens of the Moon use the spaceship of the previous volume’s protagonist to return to the planet of their ancestors. Far from achieving its stated goals of equality, communism in the U.S.E. has resulted in the establishment of a rigid class hierarchy in which a small managerial elite enjoys great privilege while the general working population is poorly paid and kept down by the repressive machinery of the state. A liberal revolution is fomenting, and Jacek has discovered a technology that causes individual atoms to explode, releasing vast amounts of destructive energy. (It’s been argued that this book, which discusses a bomb that would ‘smash that cluster of power which we call matter’ and ‘split the atom into its component pieces causing an explosion capable of destroying whole cities and continents,’ anticipates Wells’s The World Set Free.) Both the communist government and the liberal revolutionaries want to acquire the technology. Click here for more info on the trilogy.

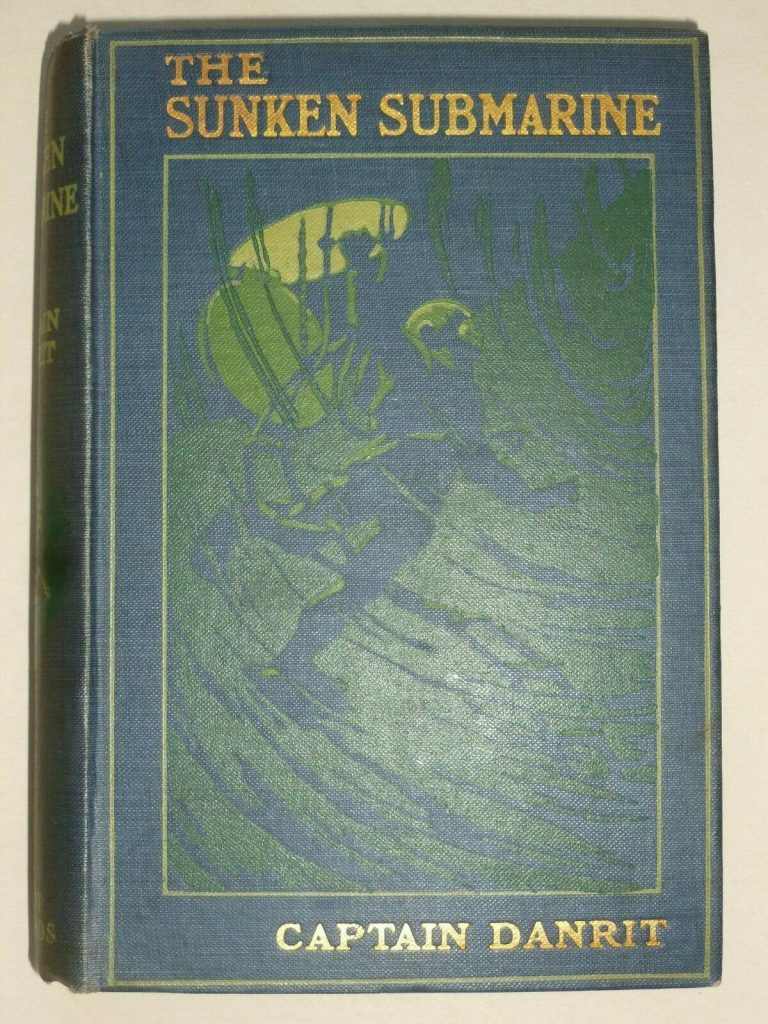

- Captain Danrit’s (Emile Driant)’s The Sunken Submarine (translation of La Guerre Fatale. Les Exploits D’un Sous-marin, 1907–1908). SFE: “Much of his sub-Verne work appeared in Le Journal des Voyages, along with authors like Louis Boussenard, whose greater skills and less exaggerated patriotism may explain their greater popularity in English-speaking markets.”

- Jules Verne’s The Eternal Adam — collected in Hier et demain (1910), a novella drafted by Verne and then greatly expanded by Verne’s son. Following an apocalypse, a group of survivors descends into barbarism. Reflects some disillusionment with science and progress. Published in English translation in 1957.

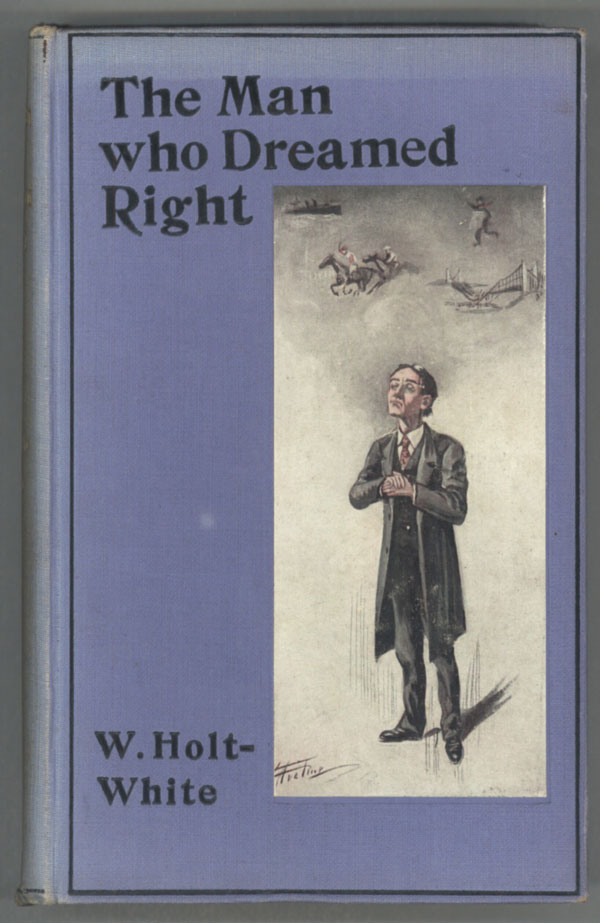

- William Holt-White’s The Man Who Dreamed Right. Science fantasy novel about Mymms, a humble British clerk who, while dreaming, can foresee the future. “Though suffering from Holt-White’s general tendency to overpack his tales to the point of parody,” the SFE says this book “rather movingly depicts an innocent man able to direct his lucid dreaming in order to predict the future, and who is destroyed at the hands of the world’s rulers (including Teddy Roosevelt), all desperate to corner his power.” Ultimately, on the eve of a world war over who will possess him, he dreams something so horrible he cannot speak about it and several nights later, he dies in his sleep — naturally, or not? Fun fact: During WWI, Holt-White was Head of the Editorial Department for a UK propaganda newsreel. See 1909 for his The Man Who Stole the Earth.

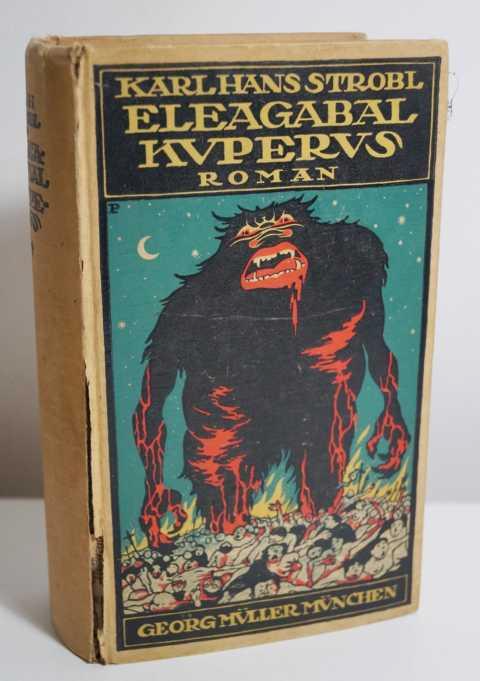

- K H Strobl’s Eleagabal Kuperus. The Austrian author’s big, sprawling novel is an apocalyptic vision of a fight between good and evil principles that involves a science-fictional attempt by the villain to deprive humanity of oxygen.

- Edwin Balmer and William MacHarg’s The Achievements of Luther Trant. Trant, an assistant in a psychological laboratory turned detective, uses psychological tests to solve crimes. A volume of nine stories, some of which would be reprinted in Gernsback’s Amazing Stories. “Based upon contemporaneous methods of the psychological laboratory, the episodes have suffered inevitably from the passage of time. But the writing was of a superior order, and at least one tale, ‘The Man Higher Up,’ is notable for the first appearance in fiction of the principle of the modern ‘lie-detector.'” — Haycraft, Murder For Pleasure. Balmer’s 1909 first novel, Waylaid by Wireless, verged on proto-sf. He remains best known for his 1932–1933 collaboration with Philip Wylie, When Worlds Collide.

- Maurice LeBlanc’s 813, an Arsène Lupin adventure set in the near future and featuring an adversary with superman characteristics bent on transforming the whole of Europe.

- Robert W. Chambers’s The Green Mouse. “Light society romance about a down-on-his-luck electrical engineer who happens on an invention that ‘broadcasts’ the erotic essence of an individual, thus attracting its ideal complementary opposite.” — Robert Eldridge, in Anatomy of Wonder

- Rudolf Hawel’s Im Reiche der Homunkuliden (In the Empire of the Homunculids), by an Austrian humorist. Professor Voraus (“Ahead”) sleeps into the year 3907, where he encounters a world of asexual robots.

- Edna W. Underwood’s “The Painter of Dead Women.” Republished in 2015 by Mike Ashley in The Feminine Future: Early Science Fiction by Women Writers.

- Henry Wallace Dowding’s The Man from Mars. Life on Mars, experienced during a two-month cataleptic trance, is described during the course of a leisurely tour of Europe.

- Richard Marsh’s A Drama of the Telephone. An uncommon book by Richard Marsh, author of gothic horror classic The Beetle (1897), the title tale here reflecting his talent for anticipating the impact of new technology.

- Lu Shi’e’s Xin Zhongguo (New China). The author’s work was primarily in the field of Wuxia as by “Qinmeizi.” His sole venture into future fiction under his own name, Xin Zhongguo often lapses into fantastical analogies (we read in SFE), as if his future Shanghai of 1951 is being observed by wide-eyed travelers from Faery. A Bellamy-esque vision of China as a thriving democracy and industrial powerhouse. Beyond his expectations of a democratic and harmonious society, with flying cars and similar wonders, Lu also speculated on refreshingly mundane improvements to everyday life. Novels like this one defined Chinese proto-sf as a genre closely associated with the discourses of an emerging nationalism; the image of a transformed future China functioned as the most significant “novum” through which to characterize the nation’s cultural dynamism.

- Stewart Edward White’s The Sign at Six — considered one of the best mad scientist stories. A sequel to The Mystery — see 1907 installment in this series, A mad Scientist threatens to cut off light, sound, and heat from New York City. Originally appeared in three parts in 1910, as “The City of Dread” in The Popular Magazine; in 1912 as a book. “A second incident in the life of Percy Darrow, scientific playboy, as he tracks down a mad scientist — Bleiler. See Anatomy of Wonder.

- Jack London’s “Goliah: A Utopian Essay” (February 1910 The Bookman), in which a “scientific superman” masters the ultimate energy source, Energon, becomes master of the world’s fate, and inaugurates a millennium of international socialism.

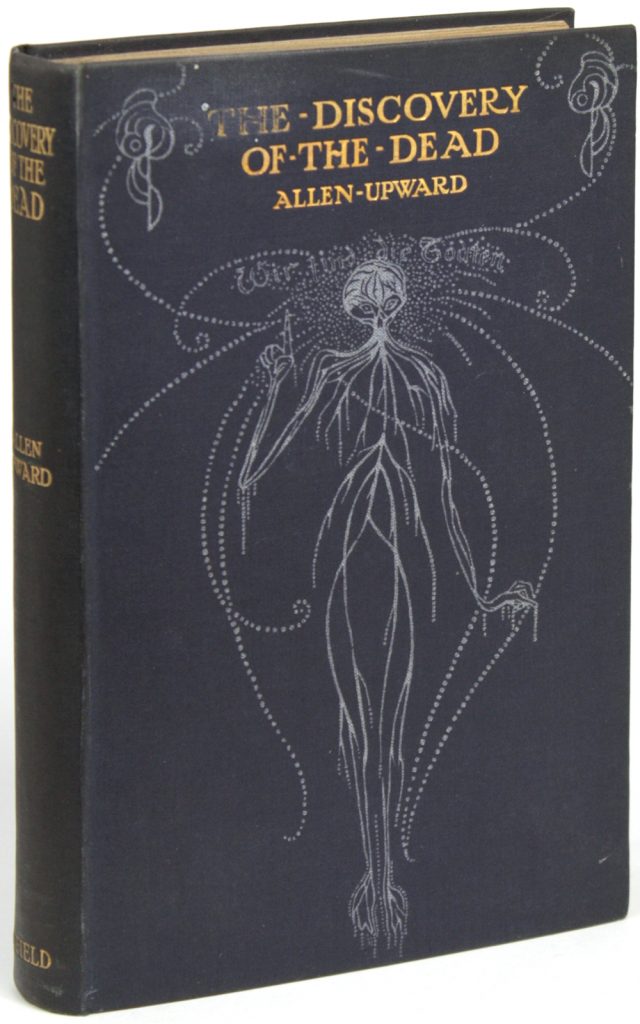

- Allen Upward’s The Discovery of the Dead. Scientific romance utilizing occult doctrines in a novel manner. Russian savant detects and communicates with ‘necromorphs,’ human survivals who reveal a spiritual hierarchy in the Beyond roughly analogous to Hell, Limbo and Heaven. Told in the form of reportage which encloses a scientific memoir. Edgar Allan Poe is interviewed. Allergic to the visible spectrum, a lost race of necromorphs lives in a city at the North Pole; they themselves are haunted by “dynamorphs” from deep underground. “Ideas not original, but presentation strikingly so.” – Robert Knowlton.

- Three articles with the overtitle “The Order of the Seraphim” (1910 The New Age) by proto-sf author Allen Upward advocated – in terms of his understanding of the concept of the Übermensch in the works of Nietzsche – the founding of an ethical elite of supermen.

ALSO: Curie succeeds in isolating radium; and she defines an international standard for radioactive emissions — it was eventually named the curie. Also, her Treatise on Radiography comes out this year. First deep-sea research expedition. German physicist Theodor Wulf climbs the Eiffel Tower with an electrometer and discovers the first evidence of cosmic rays. The Principia Mathematica is a three-volume work on the foundations of mathematics written by Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell. The Manhattan Bridge (shown above) completed; Union of South Africa, with Botha as Premier; start of the Mexican revolution; W.E.B. DuBois founds the NAACP. Forster’s Howards End; Rilke’s Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge; Chesterton’s The Innocence of Father Brown (serialized 1910–1911). Harold Bindloss’s frontier adventure The Gold Trail. An American intelligentsia (Randolph Bourne, Van Wyck Brooks, etc.) begins to emerge in Greenwich Village: pragmatic philosophy, progressive education, the new liberalism of the New Republic, the renewal of American letters centered around Seven Arts.

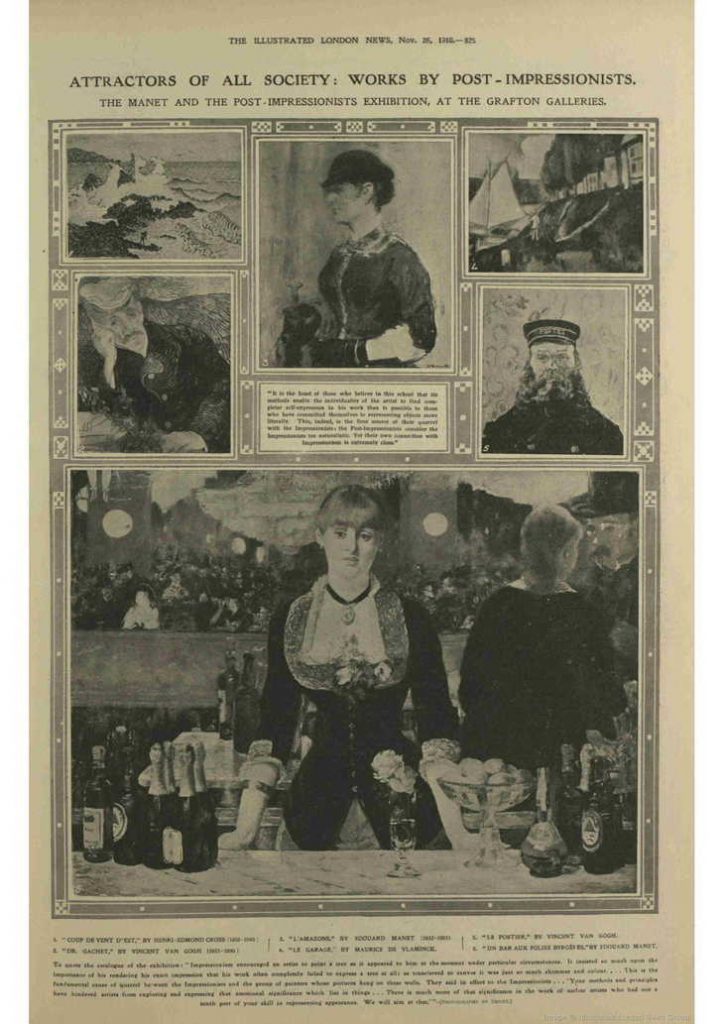

The “high modernist” period in the arts begins — which fuses Utopian Socialism (a la Tolstoy), evolutionary vitalism (Bergson), and occultist doctrines of an impending new age of cosmic consciousness. Steiner’s An Outline of Esoteric Science (also: An Outline of Occult Science) was published in 1910. Matějček coins the term Expressionism, in opposition to impressionism. Metzinger writes his important Note sur la peinture article depicting the new art movement of Picasso, Braque, and others who have “discarded traditional perspective and granted themselves the liberty of moving around objects.” Marinetti issues the manifesto “Against Past-loving Venice” in the Piazza San Marco. Likely referring to the first Post-Impressionist show in England, but with the above-mentioned context in mind, Virginia Woolf will later write: “[O]n or about December, 1910, human character changed.”

Marinetti’s magazine Poesia starts in 1910. An important advocate of Symbolist art — which contained the seeds of abstract art.

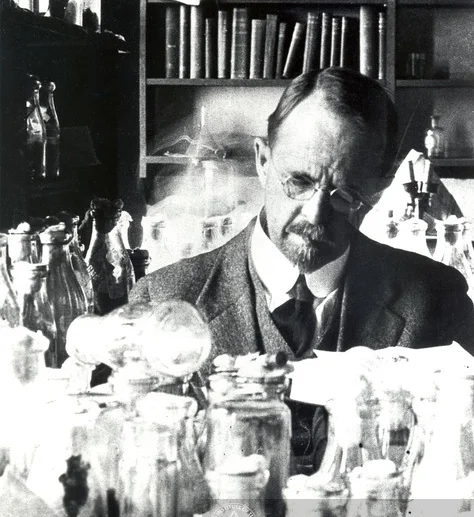

The science of genetics continues to develop. In 1910, Thomas Hunt Morgan showed that genes reside on specific chromosomes. He later showed that genes occupy specific locations on the chromosome. With this knowledge, Alfred Sturtevant, a member of Morgan’s famous fly room, using Drosophila melanogaster, provided the first chromosomal map of any biological organism.

Sérusier’s series of geometric paintings made c. 1910 convey essential implications of what has been called the geometric-occult nexus. Sacred geometry as a means of describing nature nd identifying life-forms. Many philosophers published intricate diagrams and charts. Sérusier was influenced by Plato’s Timaeus, which offers the pyramid as the origin of all other forms. (“Let it be agreed, then, both according to strict reason and according to probability, that the pyramid is the solid which is the original element and seed of fire ; and let us assign the element which was next in the order of generation to air, and the third to water. We must imagine all these to be so small that no single particle of any of the four kinds is seen by us on account of their smallness : but when many of them are collected together their aggregates are seen. And the ratios of their numbers, motions, and other properties, everywhere God, as far as necessity allowed or gave consent, has exactly perfected, and harmonised in due proportion.”)

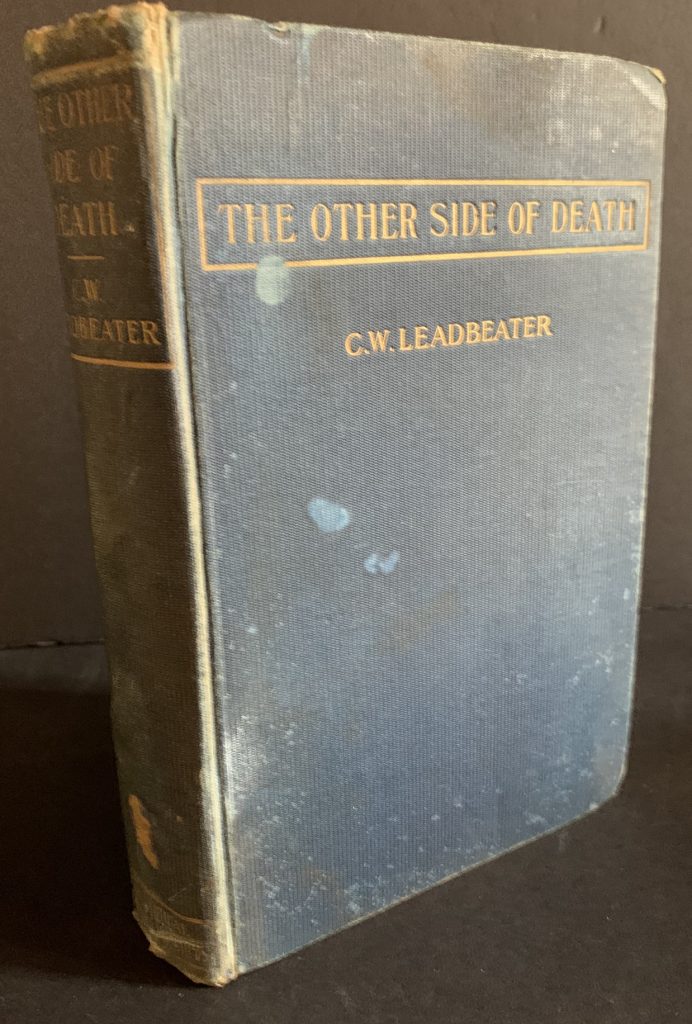

Note that the artistic possibilities of the Fourth Dimension, as well as fin-de-siecle scientific advances around radioactivity, begin to escape the proto-sf space and go mainstream around 1910. The fourth dimension — widely popularized in books like 1910’s The Fourth Dimension Simply Explained (Henry P. Manning), which frequently mentions the late-19th century German astrophysicist and psychical researcher J.C.F. Zöllner’s theories, was often equated with the new “cosmic consciousness” and placed in an artistically and philosophically productive context. Also in 1910, the widely read Theosophical writer C.W. Leadbeater’s The Other Side of Death and Clairvoyance (both of which promote Hinton’s theories about the fourth dimension) would be published in French translation… likely influencing Apollinaire and other French writers and artists at that moment. Kandinsky’s writing — heavily influenced by the Theosphical book Thought-Forms — in The Blue Rider Almanac and the treatise “On the Spiritual in Art” (which was released in 1910) were both a defense and promotion of abstract art; these ideas had an almost immediate international impact. From this point forward groups of artists moved away from representational art toward abstraction, preferring symbolic color to natural color, signs to perceived reality, ideas to direct observation. (Artists — with the exception of the Futurists, Jarry, and other ironists — made an effort to draw upon deeper and more levels of meaning, the most pervasive of which was that of the spiritual; spiritual ideas current in Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were — as noted above — a key influence.) Also appearing in France in 1910 was the criminologist and phrenologist Lombroso’s Hypnotisme et spiritisme (trans. from Italian), which reiterated Zöllner’s theories and accorded scientific respectability to occult notions of the fourth dimension.

Early cubist Max Weber wrote an article entitled “In The Fourth Dimension from a Plastic Point of View”, for Alfred Stieglitz’s July 1910 issue of Camera Work. In the piece, Weber states, “In plastic art, I believe, there is a fourth dimension which may be described as the consciousness of a great and overwhelming sense of space-magnitude in all directions at one time, and is brought into existence through the three known measurements.”

Also 1910: Claude Bragdon’s The Beautiful Necessity: Seven Essays on Theosophy and Architecture.

cf. See Tom Gibbons’s “Cubism and ‘the Fourth Dimension’ in the Context of the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Revival of Occult Idealism.”

Around 1910, groups of artists moved away from representational art toward abstraction, preferring “symbolic” color to “natural” color, signs to perceived reality, ideas to direct observation — why? Why head in this abstract direction?

See MOMA’s exhibit on abstract art.

Their art reflects a desire to express spiritual, utopian, or metaphysical ideals that cannot be expressed in traditional pictorial terms. Objective and imitative forms could not communicate from “soul to soul”; subjective and non-imitative forms could do so.

Arthur Dove was one example — his first series of abstractions was in 1910. But like many American abstract painters he also relied on the American tradition of landscape painting.

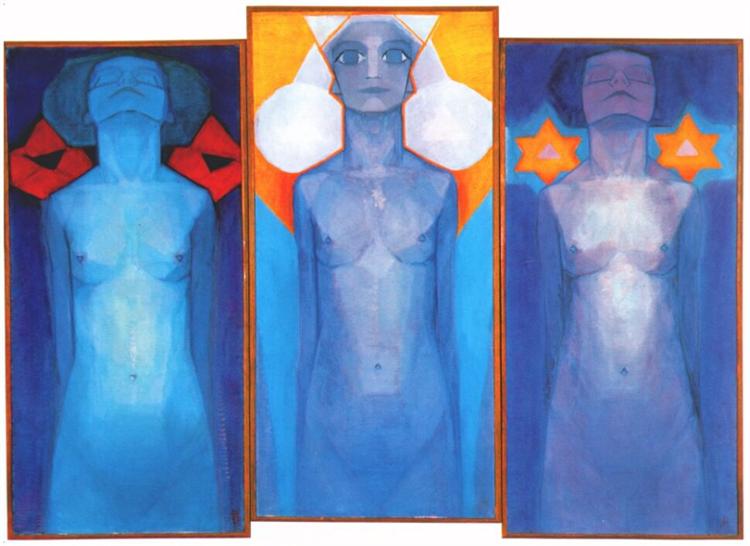

Mondrian’s transition from naturalism to abstraction begins c. 1910. Of the four “founding fathers” of abstract art, he was most consistent and systematic in his use of simple gemetric figures. His 1910–1911 painting Evolution uses wheosophical hexagrams, circles and triangles. The geometric tendency in his work around 1910–1911 adheres to the esoteric interpretation of mathematics that had already by that point been playing an important role in aesthetic thinking among theosophists. In 1911 Mondrian encountered the Cubist work of Picasso and Braque at an exhibition in Amsterdam; their method seemed to him to offer an excellent means of visualizing the essence of things by way of their dematerialization.

Mondrian eventually came to use primary geometrical forms because they are the forms most removed from physical reality. This is a platonic notion he likely pivked up from Theosophy. Spirit is most easily approached by means of a form which is closer to the Spirit – and least of all by the physical form.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin