RADIUM AGE: 1907

By:

June 4, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

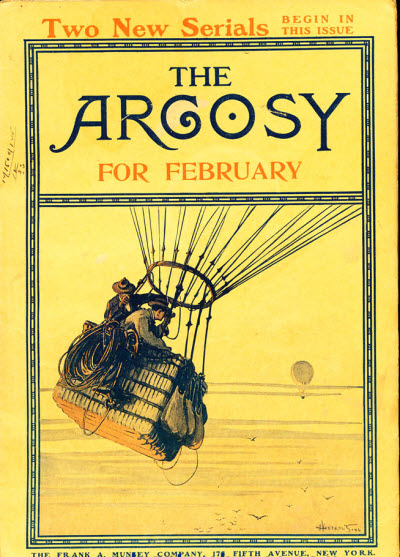

By 1907 The Argosy, which boasted a circulation of half a million, was second in circulation amongst all American magazines. (After this year, its circulation would begin to slip.) In March, Munsey introduced another specialist pulp, The Ocean, a short-lived magazine of sea stories. Meanwhile, the Monthly Magazine was renamed Blue Book.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1907.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1907, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: LITTLE GREEN MAN (a stereotypical inhabitant of outer space; an person of peculiar appearance).

- Charles Howard Hinton’s An Episode of Flatland or How a Plane Folk Discovered the Third Dimension, to which is bound up An Outline of the History of Unæa — builds on Edwin Abbott’s Flatland (1884). Published in the scientific journal Nature. The action plays out in the planar world of two-dimensional “Astria” with the primary characters partaking in various adventures, scientific and romantic. Ultimately, some “Astrians” come to accept and comprehend the reality and fullness of three-dimensions in a world beyond their immediate comprehension. See 1904 entry in this series for more info on Hinton, the mathematician who coined the term “tesseract.” Fun fact: “Any preconceptions of Hinton as some sort of narrow-minded crank are dispelled by the gentle self-irony of the book, which features two characters modeled on Hinton himself,” Rudy Rucker would write in “Life in the Fourth Dimension: C. H. Hinton and His Scientific Romances.”

- L. (Lily) Dougall’s The Christ that is to be by the author of “Pro Christo et ecclesia”. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

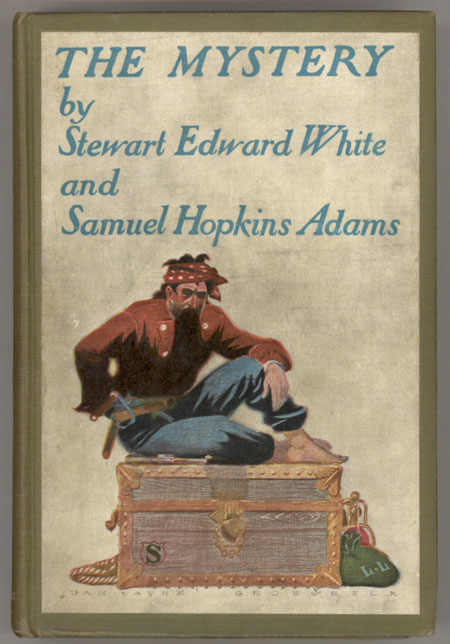

- Stewart Edward White and S.H. Adams’ The Mystery — about the ultimate energy source. Radium, sea adventure. A new radioactive element causes those who encounter it to leap into the water and drown. Supposed to be pretty good in the R.L. Stevenson manner; written up in Anatomy of Wonder. Fun facts: White was a well-regarded during his lifetime, best known for adventure novels like The Blazed Trail (1902). Starting in 1922 White and his wife wrote numerous books they said were received by channelling spirits; he also wrote books with his wife after she died. Samuel Hopkins Adams was a muckraking journalist and prolific author.

- William Hope Hodgson’s “The Voice in the Night.” Human-fungus symbiosis. Castaways are transformed by a fungus they have been obliged to eat. Included in Voices from the Radium Age (MIT Press), a 2022 story collection edited by yours truly.

- Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson’s Lord of the World — the reign of the Antichrist and the end of the world. The religion of “Humanitarianism” – a parody of the precepts underlying Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward – takes over the world. Socialism is rife in underground cities, as is euthanasia. The government maintains a tyrannical Pax Aeronautica with the aid not only of advanced airships called volors, but with the aid of the Antichrist! Benson predicted interstate highways, weapons of mass destruction, the use of aircraft to drop bombs on both military and civilian targets, and passenger air travel. Fun facts: Benson is son of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Edward White Benson (1829-1896), and brother of the fantasy and horror authors A C Benson and E F Benson. Benson was ordained as a priest in the Church of England in 1895 but converted to Catholicism in 1902 and was ordained as a priest in 1904. The SFE says: His fiction is composed with a convert’s intensity, and is deliberately propagandistic.

- Ernest Bramah’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Secret of the League (original title: What Might Have Been). In this dystopian political thriller, written at a time when the Labour Party first emerged as a serious force in British politics, and when England was roiled by labor disputes and strikes, a democratically elected British Labour Party Government — which has improved working conditions, taxed the wealthy, and reduced military spending — is overthrown through the machinations of the League, a secretive upper-class cabal. The League has hoarded fuel oil; and it engineers a consumer strike against the coal industry — the sooty heart of the Labour Party. After a civil war, the League seizes power, dismantles trade unions, and institutes a “strong” non-parliamentary regime… all of which readers are supposed to applaud! Fun fact: Bramah was a popular author who created the characters Kai Lung and blind detective Max Carrados. Though he called Bramah a decent and kindly (if misguided) man, George Orwell’s 1940 essay, “Predictions of Fascism”, credits The Secret of the League with having predicted the rise of fascism.

- William Dean Howells’s Through the Eye of the Needle: A Romance (serialized 1893-1894 Cosmopolitan; exp 1907). [Doesn’t really count as Radium Age sf.] The final volume in Howells’s “Altrurian trilogy,” following A Traveler from Altruria (serialized 1892–1893) and Letters of an Altrurian Traveler (1904). Howells’s best remembered and most significant sf remains the Altruria Utopian sequence, a deceptively mild-mannered assault on the pretensions of late-nineteenth-century US democracy and culture, seen from the perspective of a visitor from Altruria, an island in the Aegean Sea, a Lost World where an ideal high-tech socialist society has evolved in secret.

- Epes W. Sargent’s In the Land of Tomorrow. This novelette, which Moskowitz calls “effective,” was published in the short-lived pulp magazine The Ocean. Sargent is considered one of vaudeville’s most influential critics, and he wrote several textbooks on cinematology. He also wrote “Beyond the Banyan” (1909) and “The Silent Sounds” (1910). The latter is about a disintegrator device discovered amid the ruins of an ancient civilization. Neither sound very good to me.

- Kate Murray’s The Blue Star, A romance of to-day. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Louis Boussenard’s Monsieur Rien (Mr. Never) — a mad scientist story. Not one of his major works. Boussenard, who was dubbed “the French Rider Haggard” during his lifetime, wrote the sf novels Les secrets de monsieur Synthèse (1888) and Dix mille ans dans un bloc de glace (1890 — in the future, whites are bestial slaves and the dominant race are a blend of Chinese and African — with enormous psychic power. A museum of ancient artifacts shows a ludicrous understanding of the past. A bit like the plot of The Planet of the Apes.)

- Margaret L. Woods’s The Invader. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Valery Bryusov’s “The Republic of the Southern Cross” — an industrial community at the South Pole goes mad. Appeared in Valery Bryusov’s 1907 collection Zemnaya Os (Earth’s Axis). Serialized at HILOBROW in 2021. Will be reissued by MIT Press as part of the collection More Voices from the Radium Age. Note that the disturbing spatial characteristics of Antarctica — though not exactly relevant here — will become a trope in sf.

- William Hope Hodgson‘s survival/horror adventure The Boats of the “Glen-Carrig”. Not sf, but worth mentoning here because those few folks who’ve read the proto-sf pioneer William Hope Hodgson probably only know The House on the Borderland (1908) and The Boats of the “Glen-Carrig”. In which mid-18th century sailors, stranded in lifeboats when their ship, the Glen-Carrig, sinks, are stranded on an island in the midst of the Sargasso Sea. Strange wailings and murmurings permeate the night air; weird creatures slither about. The Sargasso Sea is impassable, so their escape attempts fail. One by one, the men are killed and eaten by nameless, faceless horrors: ambulatory toadstools, gigantic octopi, huge crabs, and the “weed men” (giant white leeches with human faces). Brrr. Will the narrator, a wealthy passenger forced to work side by side with the crew for survival, ever escape? Fun facts: According to China Miéville, the tentacular monster — a metaphor for the unprecedented, inexplicable, inexpressible catastrophic horror that was engulfing modernity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries — may have been popularized by Lovecraft, but it was introduced by Hodgson’s The Boats of the “Glen-Carrig”.

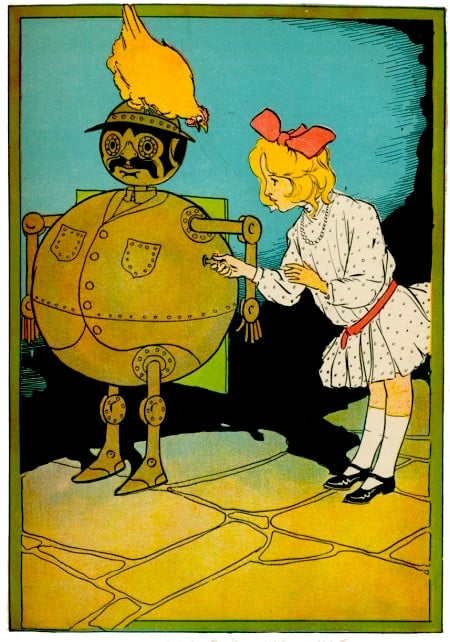

- L. Frank Baum’s Ozma of Oz. The third Oz book, and the first in which we meet one of Baum’s most delightful characters: “He was only about as tall as Dorothy herself, and his body was round as a ball and made out of burnished copper. Also his head and limbs were copper, and these were jointed or hinged to his body in a peculiar way, with metal caps over the joints, like the armor worn by knights in days of old.” From a printed card attached to its neck, Dorothy learns that Tiktok is a “Patent Double-Action, Extra-Responsive, Thought-Creating, Perfect-Talking Mechanical Man Fitted with out Special Clock-Work Attachment. Thinks, Speaks, Acts, and Does Everything but Live.” Though one of the earliest fictional appearances of true machine intelligence, Tiktok is not a free agent like his equally metallic, yet living new friend, the Tin Man — to whom he confides that “When I am wound up I do my du-ty by go-ing just as my ma-chin-er-y is made to go.” Fun fact: Baum revisited this story for his 1913 musical, The Tik-Tok Man of Oz, in which Tiktok sings: “Always work and never play!/Don’t demand a cent of pay!”

- Emilio Salgari’s Le meraviglie del Duemila — a time travel story. Salgari is an action adventure and sf story writer; his themes include scientific and technological inventions, Africa as a land of dangers and mysteries, and the wickedness of “uncivilized” indigenous peoples.

- Benson Bidwell’s The Flying Cows of Biloxi. Bidwell grafts 12-foot wings made from orange trees to cows so they can easily feed on the Spanish moss growing freely on trees in Biloxi, Mississippi. Bidwell’s successful experiment hinges on the “union of animal and vegetable substances.” Bidwell ends up producing a herd of flying cows whose calves are born with orange-tree wings that actually blossom and produce fruit that becomes a prime export to high-end department stores in Chicago. An example of American crackpot proto-sf, complete with ads for bogus products. As scholar Douglas Anderson notes, FLYING COWS OF BILOXI acquired legendary status among genre collectors because noted bookmen, including Vincent Starrett, wrote about the book but could not find it. In 1908, Benson and his son were convicted of running a confidence game and sentenced to ten years in prison.

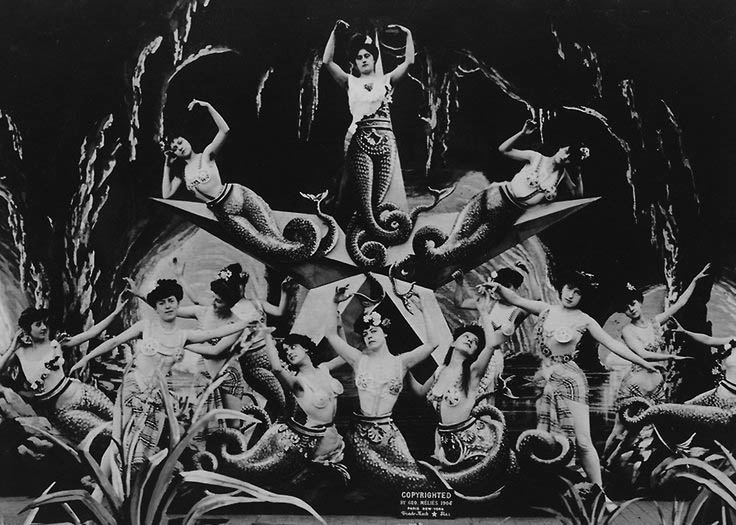

- Under the Seas (French: Deux Cents Milles sous les mers ou le Cauchemar du pêcheur) is a silent film made by Georges Méliès. A parody of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne, it follows a fisherman who dreams of traveling by submarine to the bottom of the ocean, where he encounters both realistic and fanciful sea creatures, including a chorus of naiads. PS: The plot reminds me of the 1936 Porky Pig short “Fish Tales” which gave me recurring nightmares when I saw it as a child.

- Ellison Harding’s The Demetrian. Novel of a collectivist eutopia located in America some two hundred years in the future. Published later in Britain as THE WOMAN WHO VOWED (1908).

- W. George Gribble’s “A Man and a Mermaid.” A man falls in love with a mermaid and she accepts his marriage proposal. Is it sf? Bleiler says “cleverly handled.”

- R.W. Cole’s The Death Trap. “An imaginary war with some attempt at realism … One of the better imaginary war stories …” – Bleiler

- Don Mark Lemon’s “The Mansion of Forgetfulness” — in The Black Cat. About a ray that can eradicate memory cells. Based to some extent on Poe’s “Morella.” Purple-ish prose. It’s essentially the exact plot of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

- Don Mark Lemon’s “The House that Jill Built” — in The Black Cat — about the perils of living with a (female) inventor. Silly.

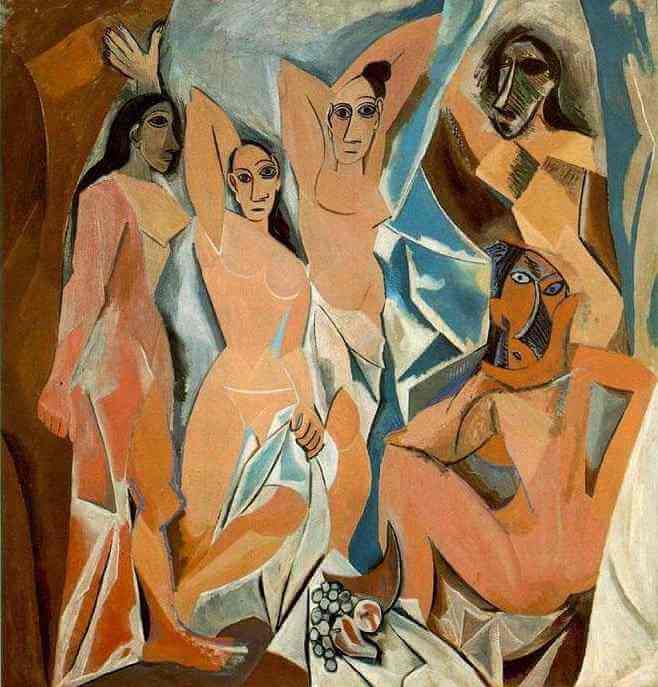

ALSO: Pavlov (shown above) studies conditioned reflexes. Lee de Forest invents the triode thermionic amplifier, starting the development of electronics as a practical technology. Leo Baekeland invents Bakelite, the first commercially produced plastic. Oklahoma becomes 46th state of the US; Rasputin gains influence at the court of Czar Nicholas II. Conrad’s The Secret Agent (depicts anarchists as vain, deluded — but the bourgeoisie is no better), Leblanc’s Arsène Lupin, gentleman-cambrioleur; Bergson’s L’Evolution créatrice (influential on sf), William James’ Pragmatism, private circulation of Henry Adams’ The Education of Henry Adams. Picasso’s 1907 painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon — a proto-Cubist work. Baden-Powell founds the Boy Scouts, the Lusitania and Mauretania are launched; first daily comic strip (it will evolve into Mutt and Jeff) launched. Schoenberg breaks through to atonality in music in his Second String Quartet. Annie Besant becomes international president of the Theosophical Society — and will remain in the post until her death in 1933. Alfred Jarry drinks himself to death.

Bergson’s Creative Evolution appears, and quickly becomes the source of the “Bergson legend.” Bergson’s project in Creative Evolution is to offer a philosophy — a metaphysics, really, appropriate for modern science — capable of accounting both for the continuity of all living beings and for the discontinuity implied in the evolutionary quality of this creation. The real obeys a certain kind of organization, namely, that of the “qualitative multiplicity” — a temporal heterogeneity, in which “several conscious states are organized into a whole, permeate one another, [and] gradually gain a richer content.” (What Sartre would call a non-totalizing totality, I think.) By its very nature, our intelligence — which is adapted to the requirements of social life in general and language in particular — fails to recognize this ultimate reality. There’s an occult aspect to this: Because a qualitative multiplicity is heterogeneous and yet interpenetrating, it is inexpressible.

In Creative Evolution, Bergson argues that there must be an original common impulse which explains the creation of all living species; this is his (in)famous élan vital. Second, the diversity resulting from evolution must be accounted for as well. (If the original impulse is common to all life, then there must also be a principle of divergence and differentiation that explains evolution; this is Bergson’s tendency theory.) Third, the two main diverging tendencies that account for evolution can ultimately be identified as instinct on the one hand and intelligence on the other. Human knowledge results from the form and the structure of intelligence, which consists of an analytic, external, hence essentially practical and spatialized approach to the world. Unlike instinct, then, human intelligence is unable to attain to the essence of life in its duration (“qualitative multiplicity”). The effort of intuition is what allows us to place ourselves back within the original creative impulse so as to overcome the numerous obstacles that stand in the way of true knowledge. The grasping of the processual, dynamic nature of time and matter described by Bergson requires a great effort of intuition, since all the exigencies of everyday social and physical human life work to push it aside.

NOTE: As a result of criticism of perceived metaphysical and irrational aspects of his thought, Bergson was dismissed by influential early twentieth-century philosophers such as Bertrand Russell (1912). Bergson’s philosophy would fall out of favor, and wouldn’t be rediscovered until Deleuze would develop his notion of the “virtual,” with its differential makeup, via reference to Creative Evolution in Bergsonism (1966).

From 1907–1911, the Swiss linguist, semiotician and philosopher Ferdinand de Saussure delivered a series of lectures at the University of Geneva. These were later collected, by two of his students, as the Cours de linguistique générale, setting forth a proposed science of “semiology.” The book would become a fundamental influence on structuralism — a general theory of culture and a methodology which implies that elements of human culture can only be fully understood by way of their relationship to a broader system.

The essence of the “Saussurean revolution” in linguistics, it has been said, is that language was prescribed to be viewed not as a chaotic totality of facts but as an edifice in which all elements are bound to one another; and his theory of a two-tiered reality about language (the first is the langue, the abstract and invisible layer, while the second, the parole, refers to the actual speech that we hear in real life.) Saussure was known to attend séances and was interested in Theosophy.

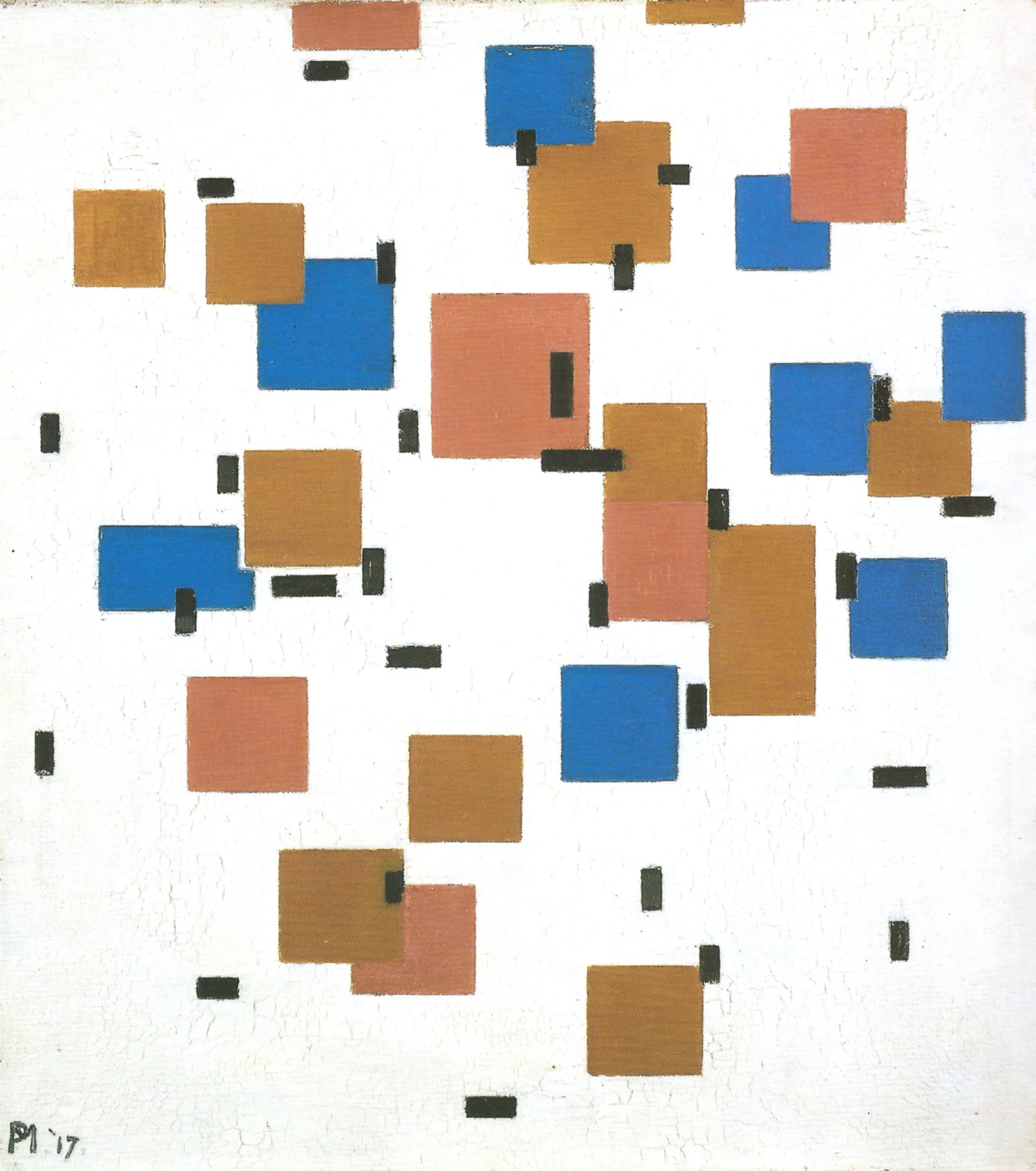

Saussure’s claim that language works through relations of difference, which place signs in opposition to one another, and his emphasis on surfacing an abstract and invisible “structure” that shapes and guides our perception and behavior… “rhymes” with what esotericists of the era were exploring. Also compare the credos of abstract artists. For example, Malevich’s The Non-Objective World (1927) says, of the abstract movement he’d founded in 1913, that “To the Suprematist, the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling, as such, quite apart from the environment in which it is called forth.”

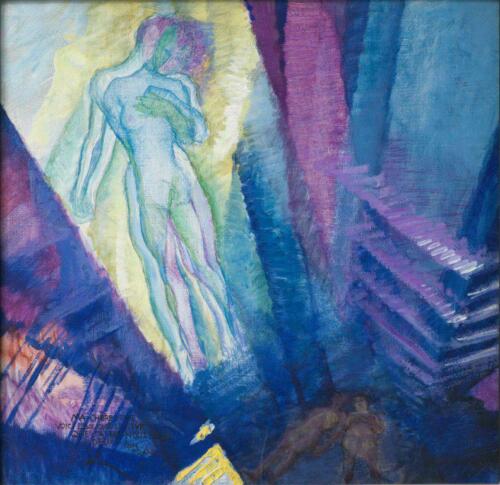

Between 1907 and 1915 painters in Europe and the USA — Kandinsky, Kupka, Mondrian, Malevich, and later we’d learn about Hilma af Klint; and others — began to create completely abstract works of art. They moved toward abstraction through their involvement with anti-modernist, spiritual issues and beliefs.

Working in relative isolation — Malevich in Russia, Kandinsky in Germany, Mondrian in the Netherlands, Kupka in France — they showed inventive ingenuity in escaping from the confines of native cultural and artistic tradition to enter a world of ideas. Theosophical diagrams — which supposedly reflected an ancient wisdom at the root of all religions — were a shared inspiration.

Art not only as a vehicle of aesthetic satisfaction but also as a conduit between the microcosm of earthly existence and the macrocosm of everlasting spiritual existence. Structuralist diagrams are also a conduit between the microcosm of “signs” that express concepts and the macrocosm of the concepts in and of themselves.

Theosophists, abstract artists, Saussure too? — suggest the essence of nature is manifested as a rhythmic geometric force. Consciousness of this force is made possible by a disciplined effort as a “medium.”

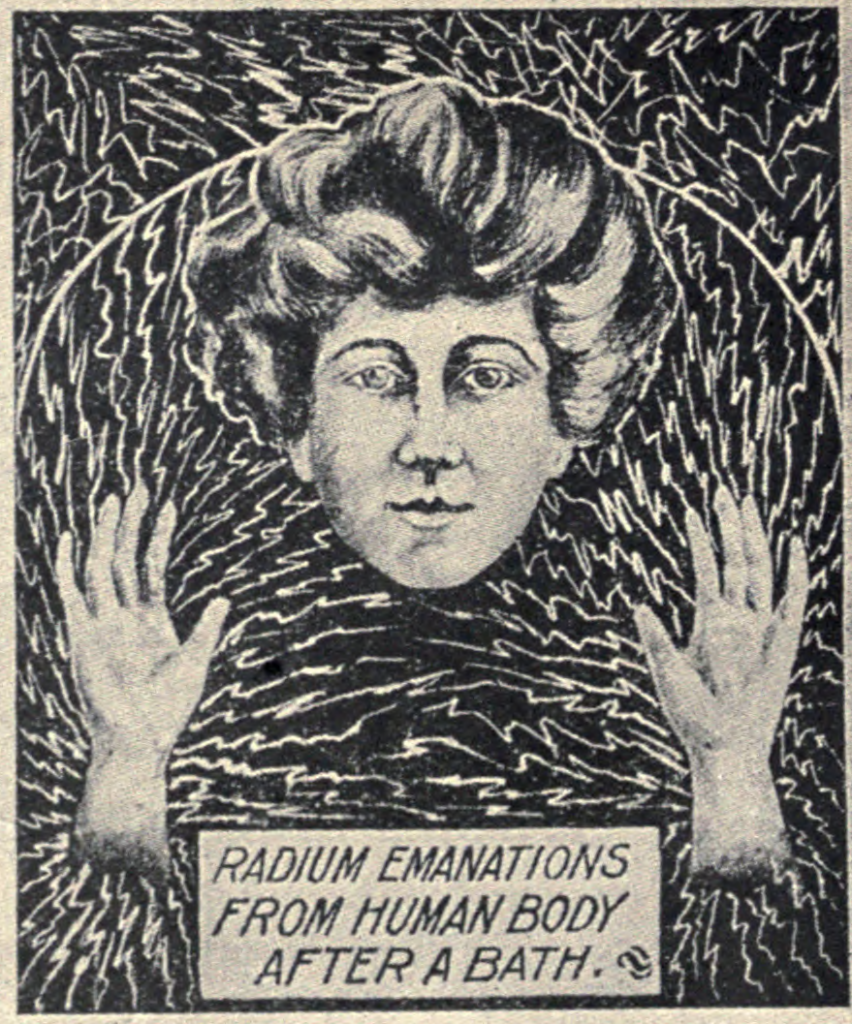

Kandinsky’s paintings were inspired by his close readings of theosophical and anthroposophical writings by Blavatsky and Steiner, and of the visual impression made by the illustrations to Annie Besant and Charles W. Ledbeater’s Thought-Forms (1905). From Theosophy Kandinsky derived his concept of vibration (he used the term Klang) — he believed that the soul is set into vibration by nature. “Words, musical tones, and colors possess the psychical power of calling forth soul vibrations” — which ultimately brings about “the attainment of knowledge.” It’s the artist’s duty to call forth soul vibrations in the viewer/audience, in order to reveal the true nature of things.

I think it’s a 1937 interview where Kandinsky says: “Abstract painting leaves behind the ‘skin’ of nature, but not its laws. Let me use the ‘big words’ cosmic laws. Art can only be great if it relates directly to cosmic laws and is subordinated to them.” He and other abstract pioneers made claims to supernatural knowledge in stating that they had penetrated the outer shell of nature while still upholding the connection with the cosmos and its laws. From the point of view of epistemology, abstractionists are doing the same work as Besant and Leadbeater’s occult chemistry. Their diagrammatic paintings are counterparts to occult chemical digarams.

Kupka, meanwhile, trained with artists who stressed geometry rather than life drawing. He had visionary experiences — of imaginary colors, infinite space, and a constant state of flux — which he translated into visual form in his paintings.

Mondrian didn’t borrow visual imagery from theosophical texts though he was very interested in Theosophy. (He’d join Amsterdam’s Theosophical Society in 1909.) His theories of art were based on a system of opposites (cf Saussure) such as male-female, light-dark, and mind-matter. These were represented in his work by right-angle lines and shapes as well as primary colors and black and white. The system he created evoked the harmonious union of opposites.

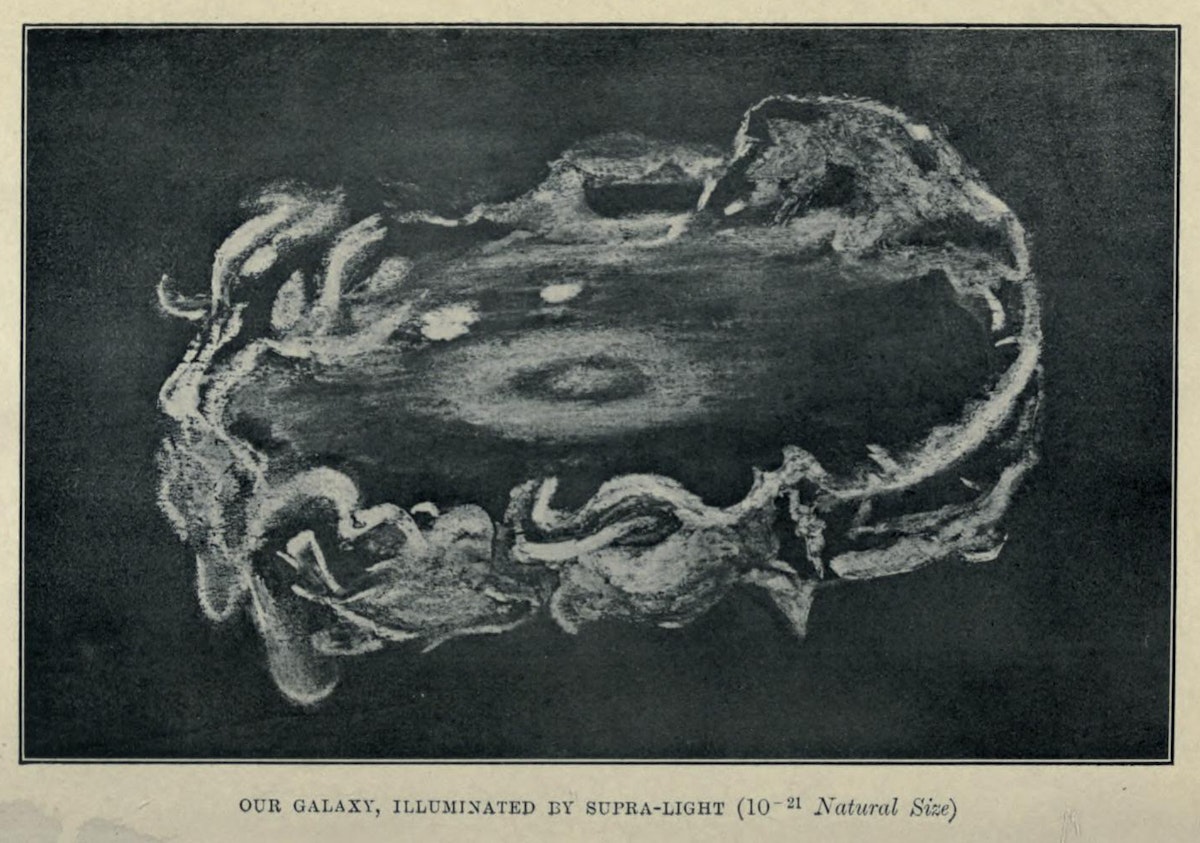

In Two New Worlds (1907), the Irish physicist Edmund Edward Fournier d’Albe argued that the recent discoveries in radioactivity and atomic structure implied the existence of an unseen spiritual universe continuous with ours. The material universe must now properly be regarded as an infinite series of worlds within worlds, which Fournier d’Albe considered to differ “only in the size of their elementary constituent particles.” He discussed two of them: the “infra-world” of atoms and electrons, and the “supra-world” of cosmic proportions. Both are, like our own world, teeming with purpose and life.” More info.

Virginia Woolf’s “A Sketch of the Past” (1907):

The shock-receiving capacity is what makes me a writer. I hazard the explanation that a shock is at once in my case followed by the desire to explain it. I feel that I have had a blow; but it is not, as I thought as a child, simply a blow from an enemy hidden behind the cotton wool of daily life; it is or will become a revelation of some order; it is a token of some real thing behind appearances; and I make it real by putting it into words. It is only by putting it into words that I make it whole; this wholeness means that it has lost its power to hurt me; it gives me, perhaps because by doing so I take away the pain, a great delight to put the severed parts together. Perhaps this is the strongest pleasure known to me. It is the rapture I get when in writing I seem to be discovering what belongs to what; making a scene come right; making a character a come together. From this I reach what I might call a philosophy; at any rate it is a constant idea of mine; that behind the cotton wool is hidden a pattern; that we — I mean all human beings — are connected with this; that the whole world is a work of art; that we are parts of the work of art. Hamlet or a Beethoven quartet is the truth about this vast mass that we call the world. But there is no Shakespeare, there is no Beethoven; certainly and emphatically there is no God; we are the words; we are the music; we are the thing itself. And I see this when I have a

shock.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin