RADIUM AGE: 1903

By:

May 10, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

The year 1903, in my periodization scheme, marks the end of the cultural decade known as the “Eighteen-Nineties.” Of course there are no hard stops and starts in culture, so it’s more accurate to describe 1903 (and 1904) as cusp years during which the Nineties end and the Nineteen-Aughts begin.

The first few years of the Twentieth Century should be regarded as a kind of interregnum between sf’s Scientific Romance era and the Radium Age. As we look at the years 1900–1904, say, we will find elements of both eras intermingling; and all traces of the Scientific Romance era will not vanish even after 1904.

Seeing Argosy‘s success, Street & Smith, a dime novel and boys’ weekly publisher, launched The Popular Magazine in 1903, which they billed as the “biggest magazine in the world” by virtue of its being two pages (the interior sides of the front and back cover) longer than Argosy. The Popular Magazine introduced color covers to pulp publishing. The Popular was one of the forerunners of the general adventure pulps that would reach their height of popularity in the 1920s and 30s. The magazine ran a total of 612 standard pulp format issues before merging with Complete Stories in 1931.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1903, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: none!

- George C. Wallis’s “The Great Sacrifice” — Martians sacrifice their planet to protect Earth from a vast meteor shower. A riposte of sorts to The War of the Worlds.

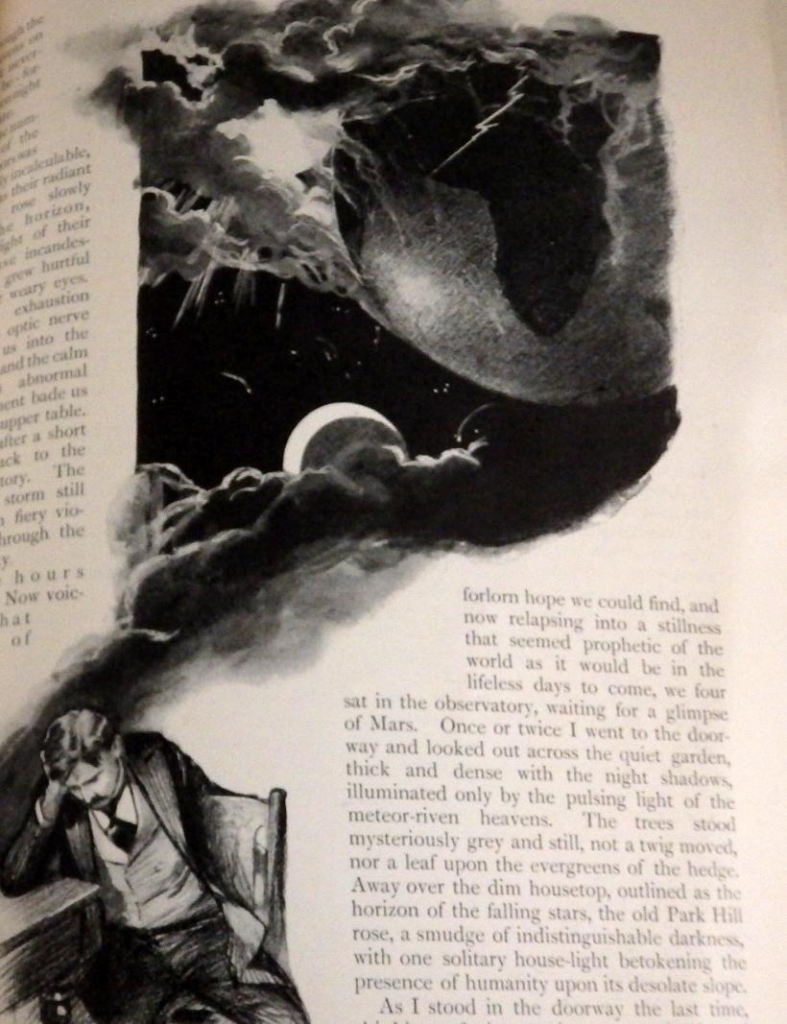

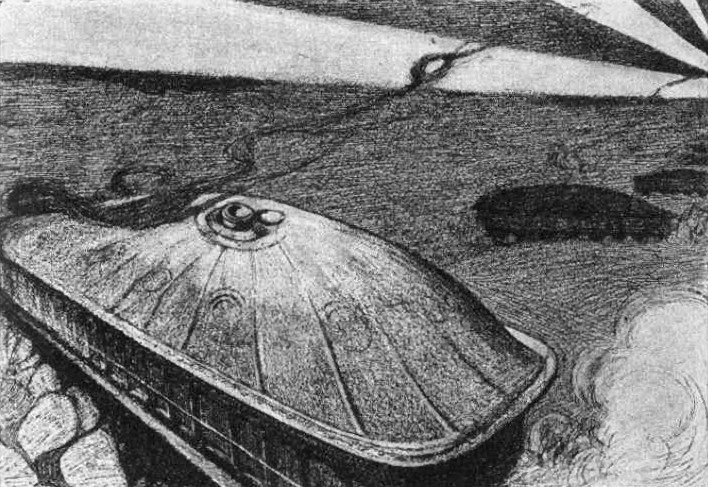

- H.G. Wells‘ “The Land Ironclads” — December issue of The Strand — in which he anticipates the devastating effect of tanks. Serialized here at HILOBROW in 2022. Will be reissued by MIT Press as part of the collection More Voices from the Radium Age.

- Don Mark Lemon’s “A Bride in Ultimate” — about a woman trapped in a diamond. Appeared in The Black Cat

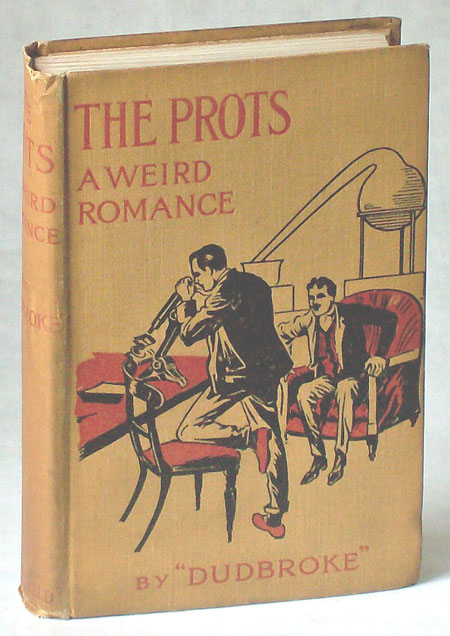

- Dudbroke’s The Prots: A Weird Romance. Biological science fiction telling of the creation of protoplasm by chemical means and the fate of the Prots, the life forms brought into being as a result of the experiment.

- John Antoine Nau’s Force ennemie. The main character is a poet who wakes up in a rubber room, locked away in a lunatic asylum, apparently at the request of a relative due to alcoholism (or perhaps jealousy.) He becomes possessed by an “Alien Force” from another planet, Kmôhoûn, whose voice is constantly screaming in his head. He then falls in love with a female inmate, Irene, whom he follows to the ends of the earth while the alien force cohabits his body. It won the inaugural Prix Goncourt in 1903.

- L.T. Meade’s “The Sorceress of the Strand” (1902–1903, in The Strand, as with Robert Eustace). About a nihilist woman with claims to Immortality; because of her mixed blood, this is an early example of the Yellow Peril meme.

- Mary Wilkins Freeman’s “The Hall Bedroom” — sort of about a tesseract but also kind of a ghost story. Falls into the gray area between occult and proto-sf.

- Owen Oliver’s “The Black Shadow” — the inhabitants of the Moon mysteriously exercise control over humans (February issue of Cassell’s Magazine). English and German professors attempt to contact the Moon’s denizens. As a result, a child and then the English professor are possessed by a lunar dark cloud. “Like most of Oliver’s fiction,” says Bleiler, “not quite successful.” The author’s real name was Joshua Albert Flynn — a British economist.

- Edith Allonby’s Jewel Sowers — see this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

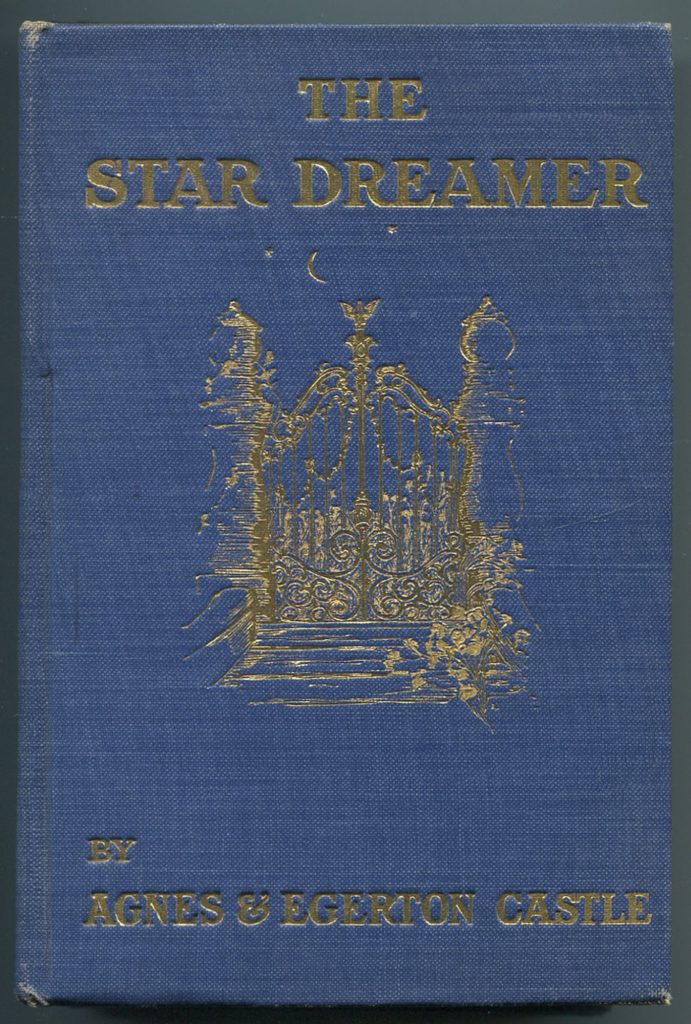

- Agnes Castle (and Egerton Castle)’s The Star Dreamer — see this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Mary Holland McNeish Kinkaid’s Walda — see this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

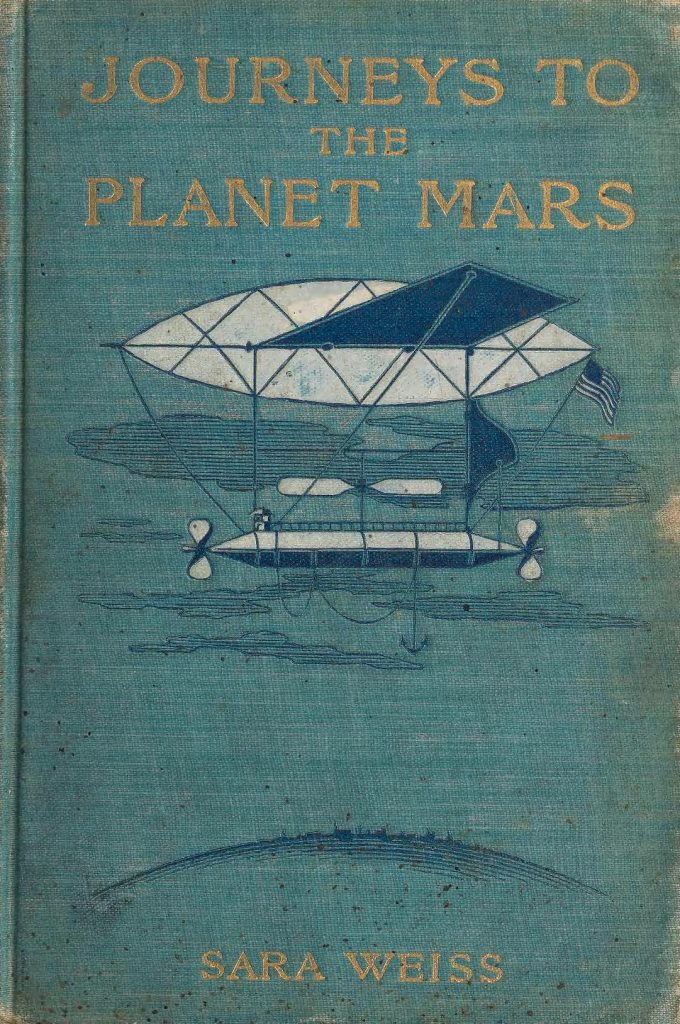

- Sara Weiss’s Journeys to the Planet Mars or Our Mission to Ento (Mars), Being a record of visits made to Ento (Mars) by Sara Weiss, Psychic, under the guidance of a Spirit Band, for the purpose of conveying to the Entoans, a knowledge of the Continuity of Life. — see this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

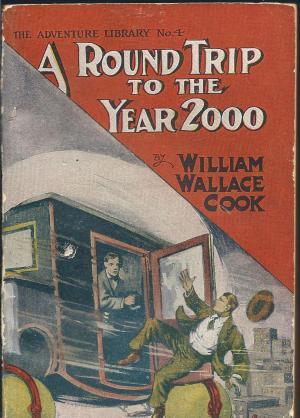

- William Wallace Cook’s A Round Trip to the Year 2000, or A Flight Through Time (July-November in Argosy; 1925, as a book). A dime-novelish satire, by the author of the extraordinary Plotto. Hack novelists travel to the year 2000, where they observe the use of metallic robot slaves and more. In fact, the future is populated by an entire colony of refugees from 1900 — all of them hack novelists. Moskowitz’s History of the Scientific Romance says this novel is well worth serious study.

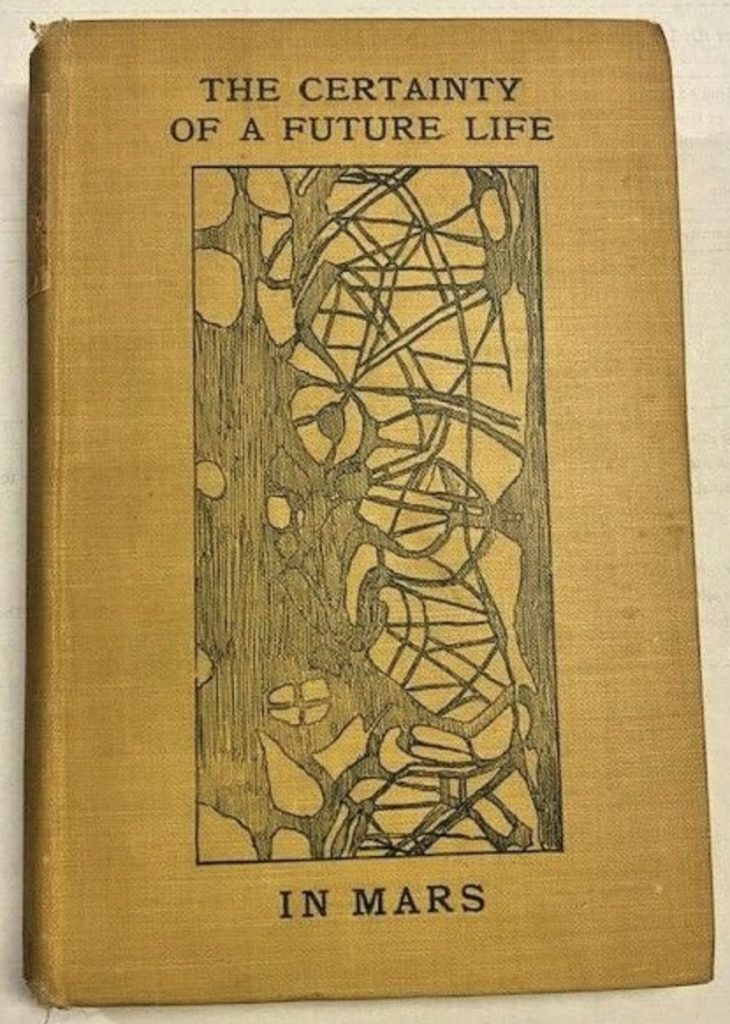

- L.P. Gratacap’s The Certainty of a Future Life in Mars. Bleiler says: “An occult tinge to interplanetary life.” A Marconi-like scientist believes that humans are reincarnated on Mars. When he dies, he communicates from Mars via a radio-like apparatus with his son. (Hey, isn’t this the premise of the Dennis Quaid movie Frequency?) The evolved Martians live under a system of democratic socialism. Bleiler concludes: “A pretentious bore.”

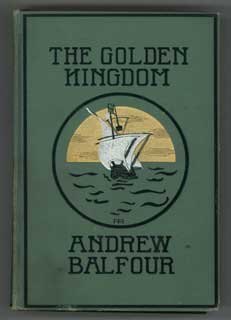

- Andrew Balfour’s The Golden Kingdom — Lost race adventure novel in which a golden city inhabited by a bronze-skinned race ruled by Whites is discovered in the interior of Africa.

- Jack London’s “The Shadow and the Flash” — two competing scientific geniuses attain invisibility, one by perfecting a pigment that absorbs all light, the other by achieving pure transparency. — collected in Beyond the Gaslight: Science in Popular Fiction 1895–1905. Collected in an eccentric anthology, Science Fiction Stories (2009, ed. Ceri Jones); it’s the only proto-sf story in the collection.

- Edgar Earl Christopher’s The Invisibles — A secret society, The Invisible Hand, plans to overthrow Czarist Russia. The scientist-members of this terrorist organization, numbering some two thousand men, have invented explosives of fantastic power, built a submarine and created artificial diamonds, which they store in their headquarters, a seemingly endless series of caves near Chattanooga, Tennessee. Unfortunately, a French detective, who has devoted much of his career to tracking down the terrorists, and his companion find a way into the cave system and begin looting the society’s treasure. The intruders are killed, but an explosion of natural gas kills all the members of the society’s council except Jean Valdemere, its leader. The submarine is destroyed and the treasure is lost, but Valdemere, a man with paranormal abilities, vows to rebuild the organization. “Plots and conspiracies, with influence from the dime novel and Victor Hugo … Of no literary merit, but a curious example of subculture fiction trying to move up.” – Bleiler

- Allen Upward’s near-future Romance of Politics sequence — Romance of Politics: High Treason (1903 chap; Note that the third edition I found online, from c. 1904, seems to be titled simply Treason) and Romance of Politics: The Fourth Conquest of England: a Sequel to “Treason” (1904 chap) – depicts the dire consequences of a Roman Catholic takeover of Britain, including a new Inquisition and the exile of the monarchy to Australia. Seems to be a response to the 1901 death of Queen Victoria, at which time surviving Jacobites — supporters of King James II and VII’s Stuart descendants, who’d been excluded from the succession by law because of their Roman Catholicism — pursued the claim of Maria Theresa of Austria-Este (or “Mary III”) to the crowns of England, Scotland, and Ireland as pretender. The first edition of Treason contains four pages advertising the Protestant Truth Society. Fun fact: Upward’s poetry was included in the first anthology of Imagist poetry, Des Imagistes, which was edited by Ezra Pound and published in 1914.

- George Sterling’s The Testimony of the Suns and Other Poems. A prominent poet and playwright and proponent of Bohemianism during the first quarter of the twentieth century. See excerpt published by HILOBROW in 2022. (Sterling was a mentor to Clark Ashton Smith.) Most of these poems are not of sf interest, but the title poem seems — to me — to be a kind of early space opera. “Cold from colossal ramparts gleam, / At their insuperable posts / The seven princes of the hosts / Who guard the holy North supreme; / Who watch the phalanxes remote / That, gathered in opposing skies, / Far on the southern wastes arise, / Marshalled by flaming Fomalhaut,” etc. It’s cosmic in scope — about the life and death of planets, galaxies, the universe. The author seems to suggest that even if humankind spreads across the galaxy (“So shall thy seed on worlds to be,/At altars built to suns afar”), we will never learn the secrets of the cosmos. Composed in 1901. Also see the poem “Mystery,” a much shorter work which seems to suggest that even our dear friends are, in the end, like stars separated from us by “great abysses” and “gulfs unshared”; and “The Directory,” which suggests that any artist who hopes their fame will endure “forever” really must grapple with the terrifying abyss of eternity: “Gone! till on worlds that serve a younger star/Estranged by voids that blot Arcturus light/Or sunder Vega from the bourne of sght,/Remoter life shall scan in vain the Deep—” which is to say, people on far-away planets don’t even know the Earth exists, and never will know it, so try to have some perspective already.

- Fred M. White’s “The Dust of Death: The Story of the Great Plague of the Twentieth Century,” “The Four Days’ Night,” “The Four White Days,” “The Invincible Force,” “A Bubble Burst.” White is perhaps best known for his six-story Doom of London Disaster series for Pearson’s Magazine – “The River of Death: A Tale of London in Peril” would appear in 1904. In each, London and the UK are subjected to a calamity — many of them related to climate change. Not published by Pearson’s but part of the same creative impulse is “The Balance of Nature” (October 1907 The Windsor Magazine), in which London is infested by genetically engineered insects.

- Harriet Prescott Spofford’s “The Ray of Displacement.” Republished in 2015 by Mike Ashley in The Feminine Future: Early Science Fiction by Women Writers.

- Edgar Franklin’s “The Hawkins Horse-Brake” — first in a series of humorous invention stories about a Mr Hawkins. Silly.

- Lazar Komarčić’s Jedna ugašena zvezda (One Extinguished Star). Said to be the first science fiction novel in Serbo-Croatian.

- Mabel Ernestine Abbott’s “Those Fatal Filaments.” Republished in 2015 by Mike Ashley in The Feminine Future: Early Science Fiction by Women Writers.

Also: Pierre Curie, Marie Curie, and Henri Becquerel share the Nobel Prize in Physics; Marie Curie is the first woman to win a Nobel. Rutherford and Soddy publish their “Law of Radioactive Change” — until then, atoms were assumed to be the indestructible basis of all matter, and although Curie had already suggested that radioactivity was an atomic phenomenon, the idea of the atoms of radioactive substances breaking up was a radically new idea. Orville and Wilbur Wright successfully fly a powered airplane. Jouffret’s Traité élémentaire de géometrie a quatre dimensions discusses the fourth dimension. Henry James’ The Ambassadors, Shaw’s Man and Superman (mocks the notion of “character”), London’s The Call of the Wild. Emmeline Pankhurst founds National Women’s Social and Political Union. Henry Ford founds the Ford Motor Company. Karl Kraus inveighing against the positivist science and philosophy of Vienna. The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. Du Bois will become a seminal work in the history of sociology and a cornerstone of African-American literature.

Jouffret’s Traité élémentaire de géométrie à quatre dimensions (Elementary Treatise on the Geometry of Four Dimensions, 1903) is a popularization of Poincaré’s Science and Hypothesis in which Jouffret describes hypercubes and other complex polyhedra in four dimensions and projects them onto the two-dimensional page. Picasso was introduced to this book before his Cubist period.

Marie Sklodowska was studying physics and mathematics at the Sorbonne in 1894 when she met Pierre Curie, who would later become her husband. Pierre, a professor at the Paris School of Physics and Chemistry, took on Marie as his doctoral student, and the two were intrigued by the work of fellow physicist Henri Becquerel, who had discovered in 1896 an “invisible radiation” emitted by uranium that caused photographic plates to darken after contact with uranium crystals. Becquerel’s work became the inspiration for Marie’s doctoral work. The breakthrough moment for the Curies occurred two years later, when Marie was researching pitchblende uranium ore from the Joachimsthal mine in Poland and noticed 2.5 times more radiation emitted from the ore than could be explained by the uranium content. She hypothesized that the pitchblende contained another element — one more radioactive than uranium. After a lengthy isolation process, Marie obtained a radium chloride precipitate and coined the term “radioactivity” to describe the radiation emitted from atomic decay. The groundbreaking subsequent work in radium isolation and purification ultimately granted Marie, Pierre, and Henri Becquerel the Nobel Prize in 1903.

In 1903, the astronomer and applied mathematician Simon Newcomb (see 1900) would claim, of astronomy, “What lies before us is an illimitable field, the existence of which was scarcely suspected ten years ago, the exploration of which may well absorb the activities of our physical laboratories, and of the great mass of our astronomical observers and investigators for as many generations as were required to bring electrical science to its present state.”

The widely read Theosophical writer C.W. Leadbeater summarizes Hinton’s writing on the fourth dimension (and how we can each learn to perceive it) in his The Other Side of Death. Alos Leadbeater’s Man Visible and Invisible (1903) has some truly far-out illustrations. This and Leadbeater’s 1899 book Clairvoyance (which also promotes Hinton’s theories) would be published in French translation in 1910… likely influencing Apollinaire and other French writers and artists at that moment.

By 1903, C.S. Peirce had begun to think of his overall philosophy in architectonic terms, and this included a broadening of his view of semiotics. Put simply, Peirce thought that all domains of thought were connected and structured hierarchically, and that logic, “in its general sense, is … only another name for semiotic.”

See his c. 1903 work on “existential graphs.” He intended his system to represent “the fundamental operations of reasoning.”

Paragraphs 394–417 (II.3. “Existential Graphs”)—from Peirce’s pamphlet A Syllabus of Certain Topics of Logic, pp. 15–23, Alfred Mudge & Son, Boston (1903).

Paragraphs 418–509 (II.4. “On Existential Graphs, Euler’s Diagrams, and Logical Algebra”)—from “Logical Tracts, No. 2” (manuscript 492), c. 1903.

Paragraphs 510–529 (II.5. “The Gamma Part of Existential Graphs”)—from “Lowell Lectures of 1903,” Lecture IV (manuscript 467).

Also see Bernhard’s 2008 paper adapting Peirce’s existential graphs to the traditional “semiotic square.”

Bergson’s “Introduction to Metaphysics” (later reproduced as the centerpiece of The Creative Mind in 1934). Became a crucial reading guide for Bergson’s philosophy as a whole, and it marked the beginning of “Bergsonism” and of its influence on Cubism and literature. Through William James’s enthusiastic reading of this essay, Bergsonism influenced American Pragmatism. Here Bergson discusses duration — that is, reality, the absolute, a mobile unity-and-multiplicity that cannot be grasped through immobile concepts — and the use of intuition in grasping duration. Consider a city, Bergson says in this essay. Analysis/intelligence, or the creation of concepts through the divisions of points of view, can only ever give us relative knowledge, a model of the city via a construction of photographs taken from every possible point of view. Analysis/intelligence can never give us the rich experience of walking in the city itself; only intuition — which allows us to in a sense enter into the things in themselves, what James called “radical empiricism” — can do so.

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s The Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices. Along with the Frenchman Robert Esnault-Pelterie, the Germans Hermann Oberth and Fritz von Opel, and the American Robert H. Goddard, Tsiolkovsky is one of the founding fathers of modern rocketry and astronautics.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin