OFF-TOPIC (38)

By:

March 7, 2022

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This episode, we seek a common graphic language for all the world’s creations, with two of the artform’s, and the earth’s, most intelligent lifeforms…

If we could talk to the animals, would we listen anyway? We humans tend not to open messages passed up the food chain, and to be the last ones off of our own sinking ships. Comics, though, with their anthropomorphic characters, have always been a primary route for attempting to get into animals’ heads (and get what they might have to say through ours). It’s part of a long tradition of folklore stretching from Balaam’s Ass to Charlotte’s Web. “Anthropomorphic” may be a comparison which gives us too much credit, but the cartoon canon undeniably transfers a number of exclusively human traits to the other species with whom we share as little of the planet as we can get away with.

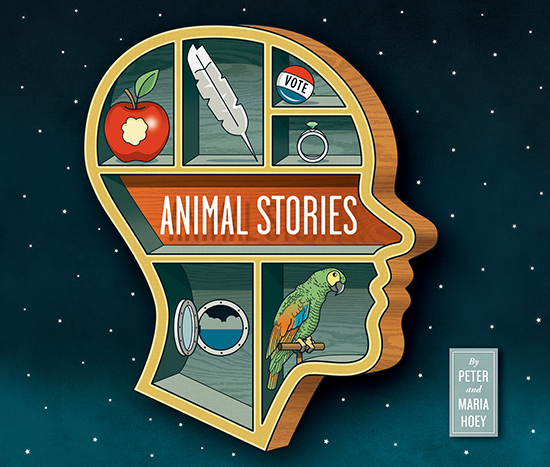

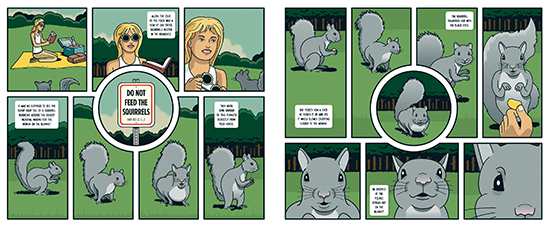

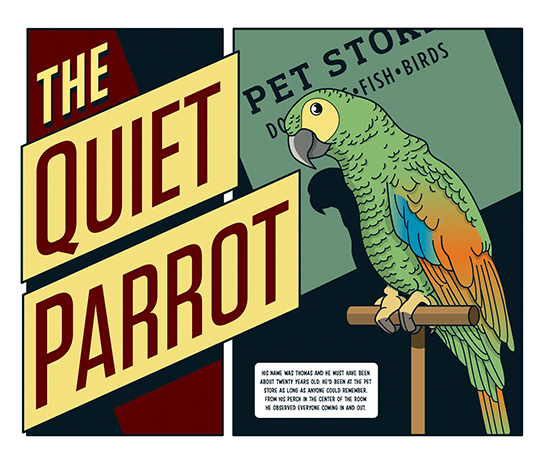

No such mistake is made in Animal Stories (Top Shelf), the new graphic novel from writer-artist Peter and artist-colorist Maria Hoey; the gulfs remain wide and the translation sustains significant losses. A solitary school-age girl and a lonely young man each relate best to the pigeons they keep; the girl conducts a mysterious dialogue in notes conveyed by an unfamiliar carrier pigeon, cast into the sky like unanswered messages in bottles thrown on the sea the young man ships out to. A non-talking dog is deferred to as the current President of the United States, his every bark and pee divined for meaning. A man’s cat disappears every few nights on unknown journeys and drags back some sinister remnants from her other lives. An unwitting couple find their roles with the rest of the animal kingdom reversed in a strange rewind of the Adam & Eve story in a public park; “game” and pet-shop creatures go on a kind of general strike, delivering a direct parting message way too late for us to hear it.

The hints of shapeshifting, reincarnation, telepathy and spirit-bonds of the type that thread humans and other animals together throughout myth, fable, storybook, and sci-fi are pervasive but never verified. Whether the human characters who interact, in special affinity or antagonism, with specific animals are projecting their own personalities, in touch with higher truths, or in denial about miracles right in front of them, is left unanswerable. But everyone, on two legs, four, or on wings, pursues their desired destiny and stays true to their nature — be it inquisitive, oblivious, benevolent or venal — played out in a fond, vaguely ominous Mainstreet fairyland of luminous whimsy and dazed dreamlike dread. I made contact with the authors to work out what’s being communicated…

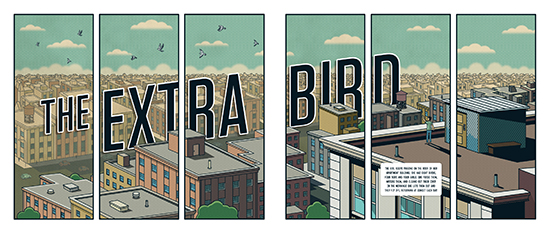

HILOBROW: We’re all familiar with those microscopic photos that show how, to a dust mite, our forearms are a forest, etc. Even humans’ point-of-view can create different worlds in the same space. From the first story we’re reminded of this sense in “The Extra Bird,” so much of which takes place in the world of the urban canopy, so to speak — the neglected, mysterious landscape of rooftops. “Noah’s Mark” takes place in the tabula rasa of the middle of an ocean, and the human delirium that makes it hard to distinguish from ancient here-there-be-dragons maps. And so forth. Is the purpose of making pictures to show us what’s unseen right around us?

PETER: Those neglected landscapes, like rooftops, and parking lots, are really appealing to me. They’re places no one pays attention to, and there’s always a big sky overhead, just like the ocean.

HILOBROW: Figurative atmospheres play a big part in this, as do the textures that fill up those vacant spaces. Maria, do you have a similar affinity for these rich, blank slates? What part do your shadows and palettes play in the personality of the scenes (and their people), and what is the dialogue like between Pete’s images and your mind’s eye?

MARIA: For Animal Stories each story has its own palette, a subtle touch to tie into the idea they are stand-alone stories, as well as a part of the whole. A subtle color-code that emphasizes the individual tale, but harmonious enough to also read straight through.

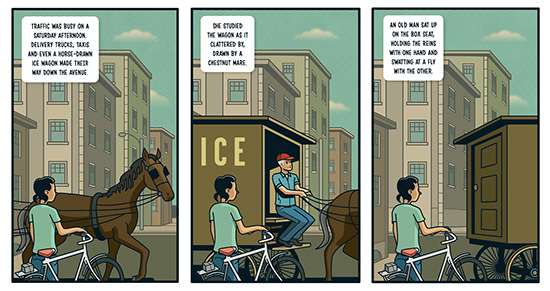

HILOBROW: Related to that is the thought of the spiritual palimpsest — lingering layers of the vanished atmospheres of a single place. These stories exist in a kind of composite afterlife, where people check their smart phones while horse-drawn wagons roll past, yet where everything fits. These times do feel kind of like a shore on which the salvage of past centuries keeps piling up and finding its spot in the pattern. What is your own understanding of the historical slippage in these stories?

MARIA: We do share a similar vision, for sure. I watched the 2021 Paul Schrader film The Card Counter this weekend (Pete had just seen it and reco’d it). It’s fabulous, and what struck me while watching it is there’s a shared vibe to our work. Unmistakably American, not restricted to a particular time, and all with an overhanging mystery and strangeness that’s never completely revealed. In this film it was clear from the plot that it had to be present-day, but from scene to scene it was out-of-time. The cars were not exactly new. The technology was not exactly new. And so on. It allowed the viewer to settle into this created world having had any distraction of specific time stripped away.

This same out-of-time-ness allows our readers to accept these tales in Animal Stories as a whole world of its own.

PETER: The horse-drawn ice wagon in “The Extra Bird” is the only remnant left from the original animal story. I ended up cutting it out because it didn’t fit with the others but it was the inspiration for all of them. I left that one scene in because it was the point of connection between the two stories.

HILOBROW: This is an intriguing trail into a book we didn’t read — what does the “lost” story say about what you had originally envisioned for this book?

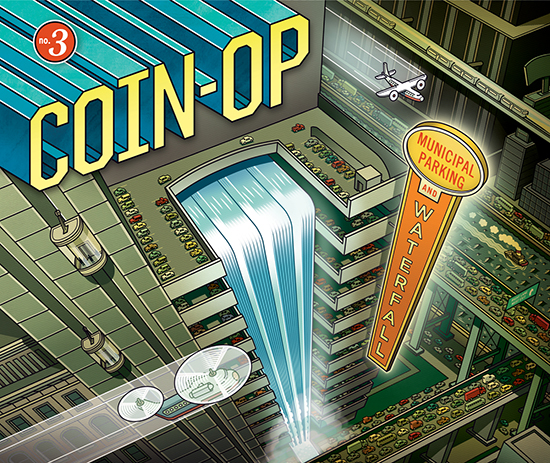

PETER: “The Lucky Hat” was originally a story that I wrote with the intention of turning it into a comic for our Coin-Op series. The main character was a benignly neglected draft horse who through a series of events transcends his dreary life.

In the story, the horse pulls an ice-wagon through the streets of New Orleans. One of his owner’s clients is a gambler who owns a nightclub in the Quarter. The gambler is fantastically lucky because of the straw hat he wears. Unbeknownst to everyone, he stole it from a voodoo queen in a rigged card game. By always wearing the hat, he embarks on an epic winning spree.

One day, as the horse and wagon wait outside his establishment a wind lifts the straw boater off his head and drops it in front of the horse. The hose eats the hat and internalizes the luck.

The gambler and his men are going to cut the horse open to get the hat back. The owner is screaming for the police as a crowd gathers. At that moment the horse grows wings, breaks out of his harness and flies off.

As I was writing it, I had the idea of other animal-centered stories that would connect to each other. The characters in one story would appear in another story, as minor characters in the background. Those stories came together quickly, starting with “Outside Cat” and “The Extra Bird.” The problem was “The Lucky Hat” didn’t really fit. A different time and place from the others.

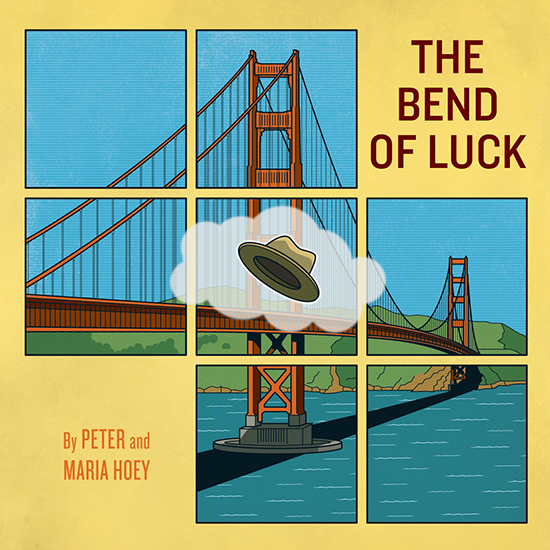

I ended up taking the idea of the lucky hat and began another, much longer story. This took shape as The Bend of Luck, our second graphic novel. It will be published later this year by Top Shelf.

I would still like to write a good horse story, like the ones Patricia Highsmith wrote. I live in a rural part of Northern California and there’s a lot of horses around. They’re interesting animals.

HILOBROW: Evacuations, exoduses — they are all through this book, with animals deserting, conspiring, or rebelling against us. At the same time the news is full of, and pop culture transfixed with, mass migrations, seceding states, nature activating defense mechanisms against us. Is this book the waking dream that blurred together those anxieties and visions?

PETER: Migrations are going on all the time, all around us. Other people, groups of animals, even insects. We like to think that we understand all this and can look at it in “context.” But that’s not really true.

HILOBROW: The book has many echoes of the Bible, including a possible relocation of the Garden of Eden to an unnamed city’s midtown park — but what most puts me in mind of the Bible in your book is the disjunction; it feels like the same story is being told from different starting points and stitched together. Did you go for those gaps? Were there pieces you intentionally left out?

PETER: In 1988, Polish filmmaker Krystof Kieslowski made a ten-part series for Polish TV called Dekalog. It was a very loose retelling of the Ten Commandments and it was set in drab apartment blocks outside Warsaw. Amidst the everyday lives and struggles of the characters were whispers of Bible stories. It made an impression on me.

There’s all sorts of moments in daily life when thoughts or events pop up for a bit, then disappear. We paper over those gaps in our everyday experience and think of it as a seamless flow, but there’s lots of gaps and misunderstandings. For that reason, I like to leave some story elements and scenes unresolved.

HILOBROW: Reading this book my head explodes with references — “The Girl Who Raised Pigeons” by Edward P. Jones (and the way his first two collections had characters that unexpectedly crossed each book); “Elegy for the Giant Tortoises” by Margaret Atwood (with its surreal procession of displaced wildlife); Cat People; even the dog whose choice of food bowl augurs life or death in Mark Russell & Steve Pugh’s Billionaire Island. Myth and fable are always reiterative and recombinant in some way; were you going for the latest circle around the campfire, so to speak?

PETER: Edward P. Jones is one of my favorite writers! I lived in D.C. for many years and his stories evoke that city so well. “The Girl Who Raised Pigeons” is a great short story, but I was more influenced by the way he would have characters from one story pop up in another. It seemed so natural. They all lived in the same neighborhood.

I used the pet store as a hub where the characters could overlap. Not necessarily knowing each other personally, but knowing each other as fellow pet owners. People you pass in the street every day, but you don’t know their names.

Cat People is a film that has at its center, the idea that there are things going on around us that are unknowable. That thought forms the backbone of Animal Stories, especially “The Outside Cat.” Regular people come up against the unknowable world and suddenly all the rules change.

HILOBROW: Your page-design dramatizes a tension between determined system and fruitful chaos — anything can happen within your frames and sequences, but the stories often have a thematic grid that structures the cognitive reception of the story (a circular panel with almost heraldic import in the middle of each stack of squares; wedge-shaped tiers in angles that alternate direction in each spread, conveying both an irregularity and a stability). Do you try out different configurations, or does the scaffold come to you with each story?

PETER: Each comic gets designed in a way that accentuates the pacing and atmosphere of the story. I think about it quite a bit before doing any drawing. I pretty much organize it in my head before picking up a pencil. The sketches go through a few drafts to add in details but the main images are all in place from the beginning.

HILOBROW: Your style employs an economy that never feels stark, and a bygone charm that feels knowingly antique but never ironic. It’s open-eyed yet humane, individual yet inclusive in a way that’s very rare. Where do you get your worldview?

PETER: Maria and I work as illustrators. We do drawings for magazines, newspapers and books. A lot of attention gets paid to just how everything looks in illustrations. Scale, color, style of drawing and composition all get pored over by art directors, designers and editors.

We bring some of that attention-to-detail into our comics. Every frame is very thought out as to what goes in it and how it relates to the other frames in the story. I like the emotional level to be on the cool side.

MARIA: I think what I like is not “nostalgia” but just good things, regardless of age. Nothing is more boring than old-timey for old-timey sake. (See steampunk, cottagecore, or “the 90’s.”) But I am the child of parents who were first-generation American (and also older when they had me), so the things I was exposed to growing up were a little out-of-step with the norm. We didn’t have 8-tracks of Meatloaf like my friends’ parents did, but we did have Broadway musical records. So I heard Rodgers and Hammerstein at home and could pick out Phil Rizzuto’s voice in “Paradise by the Dashboard Light.” On the kitchen radio, it was always tuned to an oldie station… not ’60’s oldies, but ’30’s–’40’s oldies — so that lived happily alongside the present culture that was all around us. It all had equal weight. When culture has equal weight you are more open to experiencing it all. It’s like a child who is a good eater — they are curious to taste everything. Tasting everything makes you a better artist.

HILOBROW: I could see free association playing a prominent role in the early stages of your storytelling — emeralds to green eyes to “cat burglars” to noir crime-horror, for instance. This is the kind of psychic openness that allows us to see animals as counterparts and imagine their inner lives and means of expression in our earliest childhoods. Are you aware of how these stories flow into place?

PETER: Rhyming is very important, both with words and images. The repetition brings the reader into a story in an almost subliminal way. The rhyming words operate parallel to the dialogue, but more like music. The pictures can be any kind of visual association or matching shot you want, limited only by the edge of the page.

Setting up associations and parallels between characters makes the story path seem more inevitable. The more complicated the characters’ life, the more simple their story can be.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE