THE LAND IRONCLADS (4)

By:

February 6, 2022

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize H.G. Wells’s “The Land Ironclads” for HILOBROW’s readers. Published in The Strand in 1903, this proto-sf tale contributed to Wells’s reputation as a “prophet of the future” when tanks first appeared in 1916.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10.

The war correspondent came within bawling range. “What the deuce was it? Shooting our men down!”

“Black,” said the artist, “and like a fort. Not two hundred yards from the first trench.”

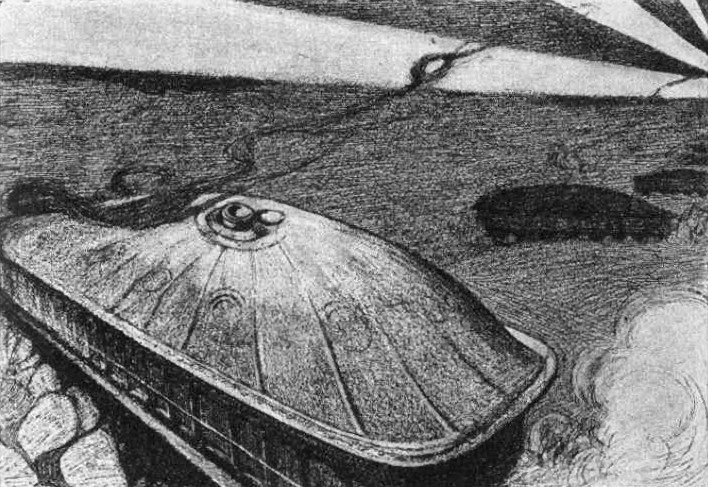

He sought for comparisons in his mind. “Something between a big blockhouse and a giant’s dish-cover,” he said.

“And they were running!” said the war correspondent.

“You’d run if a thing like that, searchlight to help it, turned up like a prowling nightmare in the middle of the night.”

They crawled to what they judged the edge of the dip and lay regarding the unfathomable dark. For a space they could distinguish nothing, and then a sudden convergence of the searchlights of both sides brought the strange thing out again.

In that flickering pallor it had the effect of a large and clumsy black insect, an insect the size of an ironclad cruiser, crawling obliquely to the first line of trenches and firing shots out of portholes in its side. And on its carcass the bullets must have been battering with more than the passionate violence of hail on a roof of tin.

Then in the twinkling of an eye the curtain of the dark had fallen again and the monster had vanished, but the crescendo of musketry marked its approach to the trenches.

They were beginning to talk about the thing to each other, when a flying bullet kicked dirt into the artist’s face, and they decided abruptly to crawl down into the cover of the trenches. They had got down with an unobtrusive persistence into the second line, before the dawn had grown clear enough for anything to be seen. They found themselves in a crowd of expectant riflemen, all noisily arguing about what would happen next. The enemy’s contrivance had done execution upon the outlying men, it seemed, but they did not believe it would do any more. “Come the day and we’ll capture the lot of them,” said a burly soldier.

“Them?” said the war correspondent.

“They say there’s a regular string of ’em, crawling along the front of our lines…. Who cares?”

The darkness filtered away so imperceptibly that at no moment could one declare decisively that one could see. The searchlights ceased to sweep hither and thither. The enemy’s monsters were dubious patches of darkness upon the dark, and then no longer dubious, and so they crept out into distinctness. The war correspondent, munching chocolate absent-mindedly, beheld at last a spacious picture of battle under the cheerless sky, whose central focus was an array of fourteen or fifteen huge clumsy shapes lying in perspective on the very edge of the first line of trenches, at intervals of perhaps three hundred yards, and evidently firing down upon the crowded riflemen. They were so close in that the defender’s guns had ceased, and only the first line of trenches was in action.

The second line commanded the first, and as the light grew the war correspondent could make out the riflemen who were fighting these monsters, crouched in knots and crowds behind the transverse banks that crossed the trenches against the eventuality of an enfilade. The trenches close to the big machines were empty save for the crumpled suggestions of dead and wounded men; the defenders had been driven right and left as soon as the prow of this land ironclad had loomed up over the front of the trench. He produced his field-glass, and was immediately a centre of inquiry from the soldiers about him.

They wanted to look, they asked questions, and after he had announced that the men across the traverses seemed unable to advance or retreat, and were crouching under cover rather than fighting, he found it advisable to loan his glasses to a burly and incredulous corporal. He heard a strident voice, and found a lean and sallow soldier at his back talking to the artist.

“There’s chaps down there caught,” the man was saying. “If they retreat they got to expose themselves, and the fire’s too straight….”

“They aren’t firing much, but every shot’s a hit.”

“Who?”

“The chaps in that thing. The men who’re coming up ——”

“Coming up where?”

“We’re evacuating them trenches where we can. Our chaps are coming back up the zigzags…. No end of ’em hit…. But when we get clear our turn’ll come. Rather! These things won’t be able to cross a trench or get into it; and before they can get back our guns’ll smash ’em up. Smash ’em right up. See?” A brightness came into his eyes. “Then we’ll have a go at the beggar inside,” he said….

The war correspondent thought for a moment, trying to realize the idea. Then he set himself to recover his field-glasses from the burly corporal….

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire” | Francis Stevens’s “Friend Island” | George C. Wallis’s “The Last Days of Earth” | Frank L. Pollock’s “Finis” | A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool | E. Nesbit’s “The Third Drug” | George Allan England’s “The Thing from — ‘Outside'” | Booth Tarkington’s “The Veiled Feminists of Atlantis” | H.G. Wells’s “The Land Ironclads” | J.D. Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder | Valery Bryusov’s “The Republic of the Southern Cross” | Algernon Blackwood’s “A Victim of Higher Space” | A. Merritt’s “The People of the Pit”.