THE LAND IRONCLADS (2)

By:

January 25, 2022

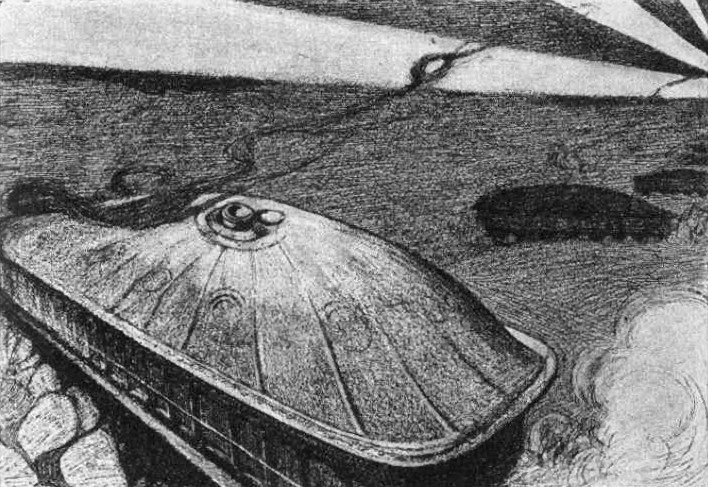

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize H.G. Wells’s “The Land Ironclads” for HILOBROW’s readers. Published in The Strand in 1903, this proto-sf tale contributed to Wells’s reputation as a “prophet of the future” when tanks first appeared in 1916.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10.

“Civilization has science, you know,” said the war correspondent. “It invented and it makes the rifles and guns and things you use.”

“Which our nice healthy hunters and stockmen and so on, rowdy-dowdy cowpunchers and negro-whackers, can use ten times better than —— What’s that?”

“What?” said the war correspondent, and then seeing his companion busy with his field-glass he produced his own. “Where?” said the war correspondent, sweeping the enemy’s lines.

“It’s nothing,” said the young lieutenant, still looking.

“What’s nothing?”

The young lieutenant put down his glass and pointed. “I thought I saw something there, behind the stems of those trees. Something black. What it was I don’t know.”

The war correspondent tried to get even by intense scrutiny.

“It wasn’t anything,” said the young lieutenant, rolling over to regard the darkling evening sky, and generalized: “There never will be anything any more for ever. Unless ——”

The war correspondent looked inquiry.

“They may get their stomachs wrong, or something — living without proper drains.”

A sound of bugles came from the tents behind. The war correspondent slid backward down the sand and stood up. “Boom!” came from somewhere far away to the left. “Halloa!” he said, hesitated, and crawled back to peer again. “Firing at this time is jolly bad manners.”

The young lieutenant was incommunicative again for a space.

Then he pointed to the distant clump of trees again. “One of our big guns. They were firing at that,” he said.

“The thing that wasn’t anything?”

“Something over there, anyhow.”

Both men were silent, peering through their glasses for a space. “Just when it’s twilight,” the lieutenant complained. He stood up.

“I might stay here a bit,” said the war correspondent.

The lieutenant shook his head. “There is nothing to see,” he apologized, and then went down to where his little squad of sun-brown, loose-limbed men had been yarning in the trench. The war correspondent stood up also, glanced for a moment at the business-like bustle below him, gave perhaps twenty seconds to those enigmatical trees again, then turned his face toward the camp.

He found himself wondering whether his editor would consider the story of how somebody thought he saw something black behind a clump of trees, and how a gun was fired at this illusion by somebody else, too trivial for public consultation.

“It’s the only gleam of a shadow of interest,” said the war correspondent, “for ten whole days.”

“No,” he said, presently; “I’ll write that other article, ‘Is War Played Out?'”

He surveyed the darkling lines in perspective, the tangle of trenches one behind another, one commanding another, which the defender had made ready. The shadows and mists swallowed up their receding contours, and here and there a lantern gleamed, and here and there knots of men were busy about small fires.

“No troops on earth could do it,” he said….

He was depressed. He believed that there were other things in life better worth having than proficiency in war; he believed that in the heart of civilization, for all its stresses, its crushing concentrations of forces, its injustice and suffering, there lay something that might be the hope of the world, and the idea that any people by living in the open air, hunting perpetually, losing touch with books and art and all the things that intensify life, might hope to resist and break that great development to the end of time, jarred on his civilized soul.

Apt to his thought came a file of defender soldiers and passed him in the gleam of a swinging lamp that marked the way.

He glanced at their red-lit faces, and one shone out for a moment, a common type of face in the defender’s ranks: ill-shaped nose, sensuous lips, bright clear eyes full of alert cunning, slouch hat cocked on one side and adorned with the peacock’s plume of the rustic Don Juan turned soldier, a hard brown skin, a sinewy frame, an open, tireless stride, and a master’s grip on the rifle.

The war correspondent returned their salutations and went on his way.

“Louts,” he whispered. “Cunning, elementary louts. And they are going to beat the townsmen at the game of war!”

From the red glow among the nearer tents came first one and then half-a-dozen hearty voices, bawling in a drawling unison the words of a particularly slab and sentimental patriotic song.

“Oh, go it!” muttered the war correspondent, bitterly.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire” | Francis Stevens’s “Friend Island” | George C. Wallis’s “The Last Days of Earth” | Frank L. Pollock’s “Finis” | A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool | E. Nesbit’s “The Third Drug” | George Allan England’s “The Thing from — ‘Outside'” | Booth Tarkington’s “The Veiled Feminists of Atlantis” | H.G. Wells’s “The Land Ironclads” | J.D. Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder | Valery Bryusov’s “The Republic of the Southern Cross” | Algernon Blackwood’s “A Victim of Higher Space” | A. Merritt’s “The People of the Pit”.