FIVE ADVENTURE TERMS

By:

December 28, 2021

Originally published by Writer’s Digest on September 21, under the headline “5 Thrilling Adventure Terms Every Writer Should Know (And Why).”

I began researching adventure-related terms fifteen years ago, as a way to procrastinate on The Idler’s Glossary (Biblioasis, 2008), an abecedarian effort devoted in large part to demonstrating that pejoratives such as lazy and slack should not be employed as synonyms for idle — idleness being a creative, contemplative, and often demanding mode of existence praised by philosophers from Aristotle to Noel Gallagher.

My analysis at the time suggested that although the idler’s existence may tend to be more sedentary than the adventurer’s, these two ideal types are counterintuitively more similar than they are different… because both eschew contentment (which is to say: quiet desperation) in favor of a life of passionate engagement and thrilling risk-taking. Ever since, I’ve sourced terminology from survivalist and gamer subcultures, hip hop and surfer slang, and military and biker jargon, not to mention Shakespeare, comic books, and extreme sports in an effort to figure out what makes the adventurer tick.

Here are a few insights I’ve gleaned that may prove of interest to my fellow writers.

ACUMEN. This term, which we use today to describe the ability — a crucial one for adventurers — to make good judgments quickly, is Latin for “sharp point.” The metaphor of sharpness will surface again and again in any study of adventure terminology. It demonstrates the transitive phenomenon whereby adventurers were formerly described in terms of their equipment – the strength of their armor, say, or the seaworthiness of their boat. Here, the adventurer’s wits are likened to the sharpness of her sword.

CAMARADERIE. When members of a team — soccer players, mountain climbers, mercenaries, you name it — develop a spirit of familiarity that goes beyond mere friendship, we describe this phenomenon with the French term camaraderie. This sounds semi-spiritual… so it’s surprising to discover that the word derives from the Spanish cámara (bedroom), which evokes one’s teammates’ snoring and smelly feet. Which is what makes camaraderie such an amazing phenomenon: Spending your every waking and sleeping hour together can easily result in deep mutual loathing, but in some cases what emerges is a family-like atmosphere of unconditional mutual trust.

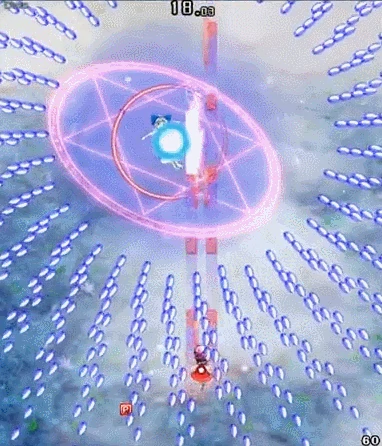

DANMAKU. Shoot-’em-up videogames in which players must dodge elaborate, at times almost psychedelically complex patterns of projectile flows, are known in Japanese as danmaku — which means, literally, “bullet curtain.” (Until recently, most games of this sort, including Espgaluda II, DoDonPachi Resurrection, and Ikaruga, came from Japan.) What’s the appeal of this sort of challenge? Rapidly figuring out the weak spots in patterns and how to exploit them. The best strategy in most cases involves moving boldly and nimbly forward — into the maelstrom. A useful lesson for adventurers.

HOIST WITH ONE’S OWN PETARD. This phrase is deployed as a colorful way to say “foiled by one’s own plan.” In the sixteenth century, a petard was a small bomb used by an invading force’s sappers and miners to blast a hole in a fortress’s wall. Literally speaking, to be hoist with one’s petard is to be blown into the air by one’s own bomb; Shakespeare popularized the figurative use of the phrase — which survives today — in Hamlet. And what is the etymology of petard, you want to know? I’m so glad you asked! The bomb’s moniker was derived from the French péter, meaning “break wind, fart.”

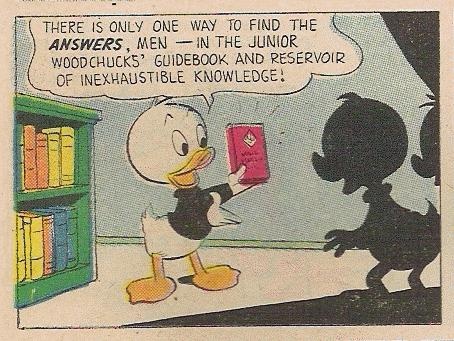

PROPÆDEUTIC ENCHIRIDION. An enchiridion is a pocket-sized book containing essential information on a subject. (The term is Ancient Greek for “fitting in the hand.”) Marcus Aurelius, we read, carried the Enchiridion of Epictetus — a manual of practical advice on achieving mental freedom and happiness, compiled by a disciple of the philosopher Epictetus — to war inside his breastplate. Meanwhile, a propædeutic (from an Ancient Greek phrase meaning “I give preliminary instruction”) is an introductory course of training. The concept of a propædeutic enchiridion containing answers to an adventurer’s every question is a fun one; fictional examples range from the Junior Woodchucks’ Guidebook in midcentury Donald Duck comics to the interactive A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer, in Neal Stephenson’s 1995 sci-fi novel The Diamond Age.

These terms and hundreds more are featured in The Adventurer’s Glossary, which McGill Queen’s University Press will publish in September. This is the third and final installment in a trilogy of language-related propædeutic enchiridia on which I’ve collaborated with the philosopher Mark Kingwell, whose introductions make explicit the sorts of questions my glossaries raise implicitly, and the acclaimed cartoonist Seth.

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE