THE MOON POOL (21)

By:

October 31, 2021

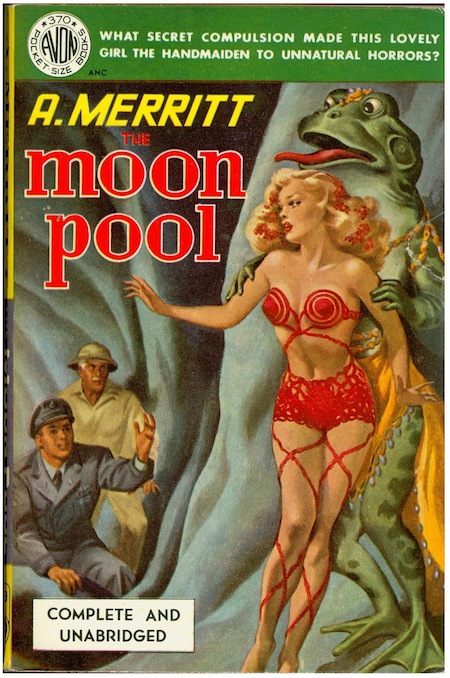

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A. Merritt’s 1919 proto-sf novel The Moon Pool for HILOBROW’s readers. Often cited as an influence on Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos, it was first published in All-Story Weekly (1918–19) as two short stories.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36.

CHAPTER XX

The Tempting of Larry

We paused before thick curtains, through which came the faint murmur of many voices. They parted; out came two—ushers, I suppose, they were—in cuirasses and kilts that reminded me somewhat of chain-mail—the first armour of any kind here that I had seen. They held open the folds.

The chamber, on whose threshold we stood, was far larger than either anteroom or hall of audience. Not less than three hundred feet long and half that in depth, from end to end of it ran two huge semi-circular tables, paralleling each other, divided by a wide aisle, and heaped with flowers, with fruits, with viands unknown to me, and glittering with crystal flagons, beakers, goblets of as many hues as the blooms. On the gay-cushioned couches that flanked the tables, lounging luxuriously, were scores of the fair-haired ruling class and there rose a little buzz of admiration, oddly mixed with a half-startled amaze, as their gaze fell upon O’Keefe in all his silvery magnificence. Everywhere the light-giving globes sent their roseate radiance.

The cuirassed dwarfs led us through the aisle. Within the arc of the inner half—circle was another glittering board, an oval. But of those seated there, facing us—I had eyes for only one—Yolara! She swayed up to greet O’Keefe—and she was like one of those white lily maids, whose beauty Hoang-Ku, the sage, says made the Gobi first a paradise, and whose lusts later the burned-out desert that it is. She held out hands to Larry, and on her face was passion—unashamed, unhiding.

She was Circe—but Circe conquered. Webs of filmiest white clung to the rose-leaf body. Twisted through the corn-silk hair a threaded circlet of pale sapphires shone; but they were pale beside Yolara’s eyes. O’Keefe bent, kissed her hands, something more than mere admiration flaming from him. She saw—and, smiling, drew him down beside her.

It came to me that of all, only these two, Yolara and O’Keefe, were in white—and I wondered; then with a tightening of nerves ceased to wonder as there entered—Lugur! He was all in scarlet, and as he strode forward a silence fell a tense, strained silence.

His gaze turned upon Yolara, rested upon O’Keefe, and instantly his face grew—dreadful—there is no other word than that for it. Marakinoff leaned forward from the centre of the table, near whose end I sat, touched and whispered to him swiftly. With appalling effort the red dwarf controlled himself; he saluted the priestess ironically, I thought; took his place at the further end of the oval. And now I noted that the figures between were the seven of that Council of which the Shining One’s priestess and Voice were the heads. The tension relaxed, but did not pass—as though a storm-cloud should turn away, but still lurk, threatening.

My gaze ran back. This end of the room was draped with the exquisitely coloured, graceful curtains looped with gorgeous garlands. Between curtains and table, where sat Larry and the nine, a circular platform, perhaps ten yards in diameter, raised itself a few feet above the floor, its gleaming surface half-covered with the luminous petals, fragrant, delicate.

On each side below it, were low carven stools. The curtains parted and softly entered girls bearing their flutes, their harps, the curiously emotion-exciting, octaved drums. They sank into their places. They touched their instruments; a faint, languorous measure throbbed through the rosy air.

The stage was set! What was to be the play?

Now about the tables passed other dusky-haired maids, fair bosoms bare, their scanty kirtles looped high, pouring out the wines for the feasters.

My eyes sought O’Keefe. Whatever it had been that Marakinoff had said, clearly it now filled his mind—even to the exclusion of the wondrous woman beside him. His eyes were stern, cold—and now and then, as he turned them toward the Russian, filled with a curious speculation. Yolara watched him, frowned, gave a low order to the Hebe behind her.

The girl disappeared, entered again with a ewer that seemed cut of amber. The priestess poured from it into Larry’s glass a clear liquid that shook with tiny sparkles of light. She raised the glass to her lips, handed it to him. Half-smiling, half-abstractedly, he took it, touched his own lips where hers had kissed; drained it. A nod from Yolara and the maid refilled his goblet.

At once there was a swift transformation in the Irishman. His abstraction vanished; the sternness fled; his eyes sparkled. He leaned caressingly toward Yolara; whispered. Her blue eyes flashed triumphantly; her chiming laughter rang. She raised her own glass—but within it was not that clear drink that filled Larry’s! And again he drained his own; and, lifting it, full once more, caught the baleful eyes of Lugur, and held it toward him mockingly. Yolara swayed close—alluring, tempting. He arose, face all reckless gaiety; rollicking deviltry.

“A toast!” he cried in English, “to the Shining One—and may the hell where it belongs soon claim it!”

He had used their own word for their god—all else had been in his own tongue, and so, fortunately, they did not understand. But the contempt in his action they did recognize—and a dead, a fearful silence fell upon them all. Lugur’s eyes blazed, little sparks of crimson in their green. The priestess reached up, caught at O’Keefe. He seized the soft hand; caressed it; his gaze grew far away, sombre.

“The Shining One.” He spoke low. “An’ now again I see the faces of those who dance with it. It is the Fires of Mora—come, God alone knows how—from Erin—to this place. The Fires of Mora!” He contemplated the hushed folk before him; and then from his lips came that weirdest, most haunting of the lyric legends of Erin—the Curse of Mora:

“The fretted fires of Mora blew o’er him in the night;

He thrills no more to loving, nor weeps for past delight.

For when those flames have bitten, both grief and joy take flight—”

Again Yolara tried to draw him down beside her; and once more he gripped her hand. His eyes grew fixed—he crooned:

“And through the sleeping silence his feet must track the tune,

When the world is barred and speckled with silver of the moon—”

He stood, swaying, for a moment, and then, laughing, let the priestess have her way; drained again the glass.

And now my heart was cold, indeed—for what hope was there left with Larry mad, wild drunk!

The silence was unbroken—elfin women and dwarfs glancing furtively at each other. But now Yolara arose, face set, eyes flashing grey.

“Hear you, the Council, and you, Lugur—and all who are here!” she cried. “Now I, the priestess of the Shining One, take, as is my right, my mate. And this is he!” She pointed down upon Larry. He glanced up at her.

“Can’t quite make out what you say, Yolara,” he muttered thickly. “But say anything—you like—I love your voice!”

I turned sick with dread. Yolara’s hand stole softly upon the Irishman’s curls caressingly.

“You know the law, Yolara.” Lugur’s voice was flat, deadly, “You may not mate with other than your own kind. And this man is a stranger—a barbarian—food for the Shining One!” Literally, he spat the phrase.

“No, not of our kind—Lugur—higher!” Yolara answered serenely. “Lo, a son of Siya and of Siyana!”

“A lie!” roared the red dwarf. “A lie!”

“The Shining One revealed it to me!” said Yolara sweetly. “And if ye believe not, Lugur—go ask of the Shining One if it be not truth!”

There was bitter, nameless menace in those last words—and whatever their hidden message to Lugur, it was potent. He stood, choking, face hell-shadowed—Marakinoff leaned out again, whispered. The red dwarf bowed, now wholly ironically; resumed his place and his silence. And again I wondered, icy-hearted, what was the power the Russian had so to sway Lugur.

“What says the Council?” Yolara demanded, turning to them.

Only for a moment they consulted among themselves. Then the woman, whose face was a ravaged shrine of beauty, spoke.

“The will of the priestess is the will of the Council!” she answered.

Defiance died from Yolara’s face; she looked down at Larry tenderly. He sat swaying, crooning.

“Bid the priests come,” she commanded, then turned to the silent room. “By the rites of Siya and Siyana, Yolara takes their son for her mate!” And again her hand stole down possessingly, serpent soft, to the drunken head of the O’Keefe.

The curtains parted widely. Through them filed, two by two, twelve hooded figures clad in flowing robes of the green one sees in forest vistas of opening buds of dawning spring. Of each pair one bore clasped to breast a globe of that milky crystal in the sapphire shrine-room; the other a harp, small, shaped somewhat like the ancient clarsach of the Druids.

Two by two they stepped upon the raised platform, placed gently upon it each their globe; and two by two crouched behind them. They formed now a star of six points about the petalled dais, and, simultaneously, they drew from their faces the covering cowls.

I half-rose—youths and maidens these of the fair-haired; and youths and maids more beautiful than any of those I had yet seen—for upon their faces was little of that disturbing mockery to which I have been forced so often, because of the deep impression it made upon me, to refer. The ashen-gold of the maiden priestesses’ hair was wound about their brows in shining coronals. The pale locks of the youths were clustered within circlets of translucent, glimmering gems like moonstones. And then, crystal globe alternately before and harp alternately held by youth and maid, they began to sing.

What was that song, I do not know—nor ever shall. Archaic, ancient beyond thought, it seemed—not with the ancientness of things that for uncounted ages have been but wind-driven dust. Rather was it the ancientness of the golden youth of the world, love lilts of earth younglings, with light of new-born suns drenching them, chorals of young stars mating in space; murmurings of April gods and goddesses. A languor stole through me. The rosy lights upon the tripods began to die away, and as they faded the milky globes gleamed forth brighter, ever brighter. Yolara rose, stretched a hand to Larry, led him through the sextuple groups, and stood face to face with him in the centre of their circle.

The rose-light died; all that immense chamber was black, save for the circle of the glowing spheres. Within this their milky radiance grew brighter—brighter. The song whispered away. A throbbing arpeggio dripped from the harps, and as the notes pulsed out, up from the globes, as though striving to follow, pulsed with them tips of moon-fire cones, such as I had seen before Yolara’s altar. Weirdly, caressingly, compellingly the harp notes throbbed in repeated, re-repeated theme, holding within itself the same archaic golden quality I had noted in the singing. And over the moon flame pinnacles rose higher!

Yolara lifted her arms; within her hands were clasped O’Keefe’s. She raised them above their two heads and slowly, slowly drew him with her into a circling, graceful step, tendrillings delicate as the slow spirallings of twilight mist upon some still stream.

As they swayed the rippling arpeggios grew louder, and suddenly the slender pinnacles of moon fire bent, dipped, flowed to the floor, crept in a shining ring around those two—and began to rise, a gleaming, glimmering, enchanted barrier—rising, ever rising—hiding them!

With one swift movement Yolara unbound her circlet of pale sapphires, shook loose the waves of her silken hair. It fell, a rippling, wondrous cascade, veiling both her and O’Keefe to their girdles—and now the shining coils of moon fire had crept to their knees—was circling higher—higher.

And ever despair grew deeper in my soul!

What was that! I started to my feet, and all around me in the darkness I heard startled motion. From without came a blaring of trumpets, the sound of running men, loud murmurings. The tumult drew closer. I heard cries of “Lakla! Lakla!” Now it was at the very threshold and within it, oddly, as though—punctuating—the clamour, a deep-toned, almost abysmal, booming sound—thunderously bass and reverberant.

Abruptly the harpings ceased; the moon fires shuddered, fell, and began to sweep back into the crystal globes; Yolara’s swaying form grew rigid, every atom of it listening. She threw aside the veiling cloud of hair, and in the gleam of the last retreating spirals her face glared out like some old Greek mask of tragedy.

The sweet lips that even at their sweetest could never lose their delicate cruelty, had no sweetness now. They were drawn into a square—inhuman as that of the Medusa; in her eyes were the fires of the pit, and her hair seemed to writhe like the serpent locks of that Gorgon whose mouth she had borrowed; all her beauty was transformed into a nameless thing—hideous, inhuman, blasting! If this was the true soul of Yolara springing to her face, then, I thought, God help us in very deed!

I wrested my gaze away to O’Keefe. All drunkenness gone, himself again, he was staring down at her, and in his eyes were loathing and horror unutterable. So they stood—and the light fled.

Only for a moment did the darkness hold. With lightning swiftness the blackness that was the chamber’s other wall vanished. Through a portal open between grey screens, the silver sparkling radiance poured.

And through the portal marched, two by two, incredible, nightmare figures—frog-men, giants, taller by nearly a yard than even tall O’Keefe! Their enormous saucer eyes were irised by wide bands of green-flecked red, in which the phosphorescence flickered. Their long muzzles, lips half-open in monstrous grin, held rows of glistening, slender, lancet sharp fangs. Over the glaring eyes arose a horny helmet, a carapace of black and orange scales, studded with foot-long lance-headed horns.

They lined themselves like soldiers on each side of the wide table aisle, and now I could see that their horny armour covered shoulders and backs, ran across the chest in a knobbed cuirass, and at wrists and heels jutted out into curved, murderous spurs. The webbed hands and feet ended in yellow, spade-shaped claws.

They carried spears, ten feet, at least, in length, the heads of which were pointed cones, glistening with that same covering, from whose touch of swift decay I had so narrowly saved Rador.

They were grotesque, yes—more grotesque than anything I had ever seen or dreamed, and they were—terrible!

And then, quietly, through their ranks came—a girl! Behind her, enormous pouch at his throat swelling in and out menacingly, in one paw a treelike, spike-studded mace, a frog-man, huger than any of the others, guarding. But of him I caught but a fleeting, involuntary impression—all my gaze was for her.

For it was she who had pointed out to us the way from the peril of the Dweller’s lair on Nan-Tauach. And as I looked at her, I marvelled that ever could I have thought the priestess more beautiful. Into the eyes of O’Keefe rushed joy and an utter abasement of shame.

And from all about came murmurs—edged with anger, half-incredulous, tinged with fear:

“Lakla!”

“Lakla!”

“The handmaiden!”

She halted close beside me. From firm little chin to dainty buskined feet she was swathed in the soft robes of dull, almost coppery hue. The left arm was hidden, the right free and gloved. Wound tight about it was one of the vines of the sculptured wall and of Lugur’s circled signet-ring. Thick, a vivid green, its five tendrils ran between her fingers, stretching out five flowered heads that gleamed like blossoms cut from gigantic, glowing rubies.

So she stood contemplating Yolara. Then drawn perhaps by my gaze, she dropped her eyes upon me; golden, translucent, with tiny flecks of amber in their aureate irises, the soul that looked through them was as far removed from that flaming out of the priestess as zenith is above nadir.

I noted the low, broad brow, the proud little nose, the tender mouth, and the soft—sunlight—glow that seemed to transfuse the delicate skin. And suddenly in the eyes dawned a smile—sweet, friendly, a touch of roguishness, profoundly reassuring in its all humanness. I felt my heart expand as though freed from fetters, a recrudescence of confidence in the essential reality of things—as though in nightmare the struggling consciousness should glimpse some familiar face and know the terrors with which it strove were but dreams. And involuntarily I smiled back at her.

She raised her head and looked again at Yolara, contempt and a certain curiosity in her gaze; at O’Keefe—and through the softened eyes drifted swiftly a shadow of sorrow, and on its fleeting wings deepest interest, and hovering over that a naive approval as reassuringly human as had been her smile.

She spoke, and her voice, deep-timbred, liquid gold as was Yolara’s all silver, was subtly the synthesis of all the golden glowing beauty of her.

“The Silent Ones have sent me, O Yolara,” she said. “And this is their command to you—that you deliver to me to bring before them three of the four strangers who have found their way here. For him there who plots with Lugur”—she pointed at Marakinoff, and I saw Yolara start—”they have no need. Into his heart the Silent Ones have looked; and Lugur and you may keep him, Yolara!”

There was honeyed venom in the last words.

Yolara was herself now; only the edge of shrillness on her voice revealed her wrath as she answered.

“And whence have the Silent Ones gained power to command, choya?”

This last, I knew, was a very vulgar word; I had heard Rador use it in a moment of anger to one of the serving maids, and it meant, approximately, “kitchen girl,” “scullion.” Beneath the insult and the acid disdain, the blood rushed up under Lakla’s ambered ivory skin.

“Yolara”—her voice was low—”of no use is it to question me. I am but the messenger of the Silent Ones. And one thing only am I bidden to ask you—do you deliver to me the three strangers?”

Lugur was on his feet; eagerness, sardonic delight, sinister anticipation thrilling from him—and my same glance showed Marakinoff, crouched, biting his finger-nails, glaring at the Golden Girl.

“No!” Yolara spat the word. “No! Now by Thanaroa and by the Shining One, no!” Her eyes blazed, her nostrils were wide, in her fair throat a little pulse beat angrily. “You, Lakla—take you my message to the Silent Ones. Say to them that I keep this man”—she pointed to Larry—”because he is mine. Say to them that I keep the yellow-haired one and him”—she pointed to me—”because it pleases me.

“Tell them that upon their mouths I place my foot, so!”—she stamped upon the dais viciously—”and that in their faces I spit!”—and her action was hideously snakelike. “And say last to them, you handmaiden, that if you they dare send to Yolara again, she will feed you to the Shining One! Now—go!”

The handmaiden’s face was white.

“Not unforeseen by the three was this, Yolara,” she replied. “And did you speak as you have spoken then was I bidden to say this to you.” Her voice deepened. “Three tal have you to take counsel, Yolara. And at the end of that time these things must you have determined—either to do or not to do: first, send the strangers to the Silent Ones; second, give up, you and Lugur and all of you, that dream you have of conquest of the world without; and, third, forswear the Shining One! And if you do not one and all these things, then are you done, your cup of life broken, your wine of life spilled. Yea, Yolara, for you and the Shining One, Lugur and the Nine and all those here and their kind shall pass! This say the Silent Ones, ‘Surely shall all of ye pass and be as though never had ye been!'”

Now a gasp of rage and fear arose from all those around me—but the priestess threw back her head and laughed loud and long. Into the silver sweet chiming of her laughter clashed that of Lugur—and after a little the nobles took it up, till the whole chamber echoed with their mirth. O’Keefe, lips tightening, moved toward the Handmaiden, and almost imperceptibly, but peremptorily, she waved him back.

“Those are great words—great words indeed, choya,” shrilled Yolara at last; and again Lakla winced beneath the word. “Lo, for laya upon laya, the Shining One has been freed from the Three; and for laya upon laya they have sat helpless, rotting. Now I ask you again—whence comes their power to lay their will upon me, and whence comes their strength to wrestle with the Shining One and the beloved of the Shining One?”

And again she laughed—and again Lugur and all the fairhaired joined in her laughter.

Into the eyes of Lakla I saw creep a doubt, a wavering; as though deep within her the foundations of her own belief were none too firm.

She hesitated, turning upon O’Keefe gaze in which rested more than suggestion of appeal! And Yolara saw, too, for she flushed with triumph, stretched a finger toward the handmaiden.

“Look!” she cried. “Look! Why, even she does not believe!” Her voice grew silk of silver—merciless, cruel. “Now am I minded to send another answer to the Silent Ones. Yea! But not by you, Lakla; by these”—she pointed to the frog-men, and, swift as light, her hand darted into her bosom, bringing forth the little shining cone of death.

But before she could level it the Golden Girl had released that hidden left arm and thrown over her face a fold of the metallic swathings. Swifter than Yolara, she raised the arm that held the vine—and now I knew this was no inert blossoming thing.

It was alive!

It writhed down her arm, and its five rubescent flower heads thrust out toward the priestess—vibrating, quivering, held in leash only by the light touch of the handmaiden at its very end.

From the swelling throat pouch of the monster behind her came a succession of the reverberant boomings. The frogmen wheeled, raised their lances, levelled them at the throng. Around the reaching ruby flowers a faint red mist swiftly grew.

The silver cone dropped from Yolara’s rigid fingers; her eyes grew stark with horror; all her unearthly loveliness fled from her; she stood pale-lipped. The Handmaiden dropped the protecting veil—and now it was she who laughed.

“It would seem, then, Yolara, that there is a thing of the Silent Ones ye fear!” she said. “Well—the kiss of the Yekta I promise you in return for the embrace of your Shining One.”

She looked at Larry, long, searchingly, and suddenly again with all that effect of sunlight bursting into dark places, her smile shone upon him. She nodded, half gaily; looked down upon me, the little merry light dancing in her eyes; waved her hand to me.

She spoke to the giant frog-man. He wheeled behind her as she turned, facing the priestess, club upraised, fangs glistening. His troop moved not a jot, spears held high. Lakla began to pass slowly—almost, I thought, tauntingly—and as she reached the portal Larry leaped from the dais.

“Alanna!” he cried. “You’ll not be leavin’ me just when I’ve found you!”

In his excitement he spoke in his own tongue, the velvet brogue appealing. Lakla turned, contemplated O’Keefe, hesitant, unquestionably longingly, irresistibly like a child making up her mind whether she dared or dared not take a delectable something offered her.

“I go with you,” said O’Keefe, this time in her own speech. “Come on, Doc!” He reached out a hand to me.

But now Yolara spoke. Life and beauty had flowed back into her face, and in the purple eyes all her hosts of devils were gathered.

“Do you forget what I promised you before Siya and Siyana? And do you think that you can leave me—me—as though I were a choya—like her.” She pointed to Lakla. “Do you—”

“Now, listen, Yolara,” Larry interrupted almost plaintively. “No promise has passed from me to you—and why would you hold me?” He passed unconsciously into English. “Be a good sport, Yolara,” he urged, “You have got a very devil of a temper, you know, and so have I; and we’d be really awfully uncomfortable together. And why don’t you get rid of that devilish pet of yours, and be good!”

She looked at him, puzzled, Marakinoff leaned over, translated to Lugur. The red dwarf smiled maliciously, drew near the priestess; whispered to her what was without doubt as near as he could come in the Murian to Larry’s own very colloquial phrases.

Yolara’s lips writhed.

“Hear me, Lakla!” she cried. “Now would I not let you take this man from me were I to dwell ten thousand laya in the agony of the Yekta’s kiss. This I swear to you—by Thanaroa, by my heart, and by my strength—and may my strength wither, my heart rot in my breast, and Thanaroa forget me if I do!”

“Listen, Yolara”—began O’Keefe again.

“Be silent, you!” It was almost a shriek. And her hand again sought in her breast for the cone of rhythmic death.

Lugur touched her arm, whispered again, The glint of guile shone in her eyes; she laughed softly, relaxed.

“The Silent Ones, Lakla, bade you say that they—allowed—me three tal to decide,” she said suavely. “Go now in peace, Lakla, and say that Yolara has heard, and that for the three tal they—allow—her she will take council.” The handmaiden hesitated.

“The Silent Ones have said it,” she answered at last. “Stay you here, strangers”—-the long lashes drooped as her eyes met O’Keefe’s and a hint of blush was in her cheeks—”stay you here, strangers, till then. But, Yolara, see you on that heart and strength you have sworn by that they come to no harm—else that which you have invoked shall come upon you swiftly indeed—and that I promise you,” she added.

Their eyes met, clashed, burned into each other—black flame from Abaddon and golden flame from Paradise.

“Remember!” said Lakla, and passed through the portal. The gigantic frog-man boomed a thunderous note of command, his grotesque guards turned and slowly followed their mistress; and last of all passed out the monster with the mace.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.