OFF-TOPIC (34)

By:

October 16, 2021

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This thrilling episode, for our ongoing season of stretched time and suspended moments, a commentary track on serial narratives organically composed, master-planned, intermittent and out-of-sequence…

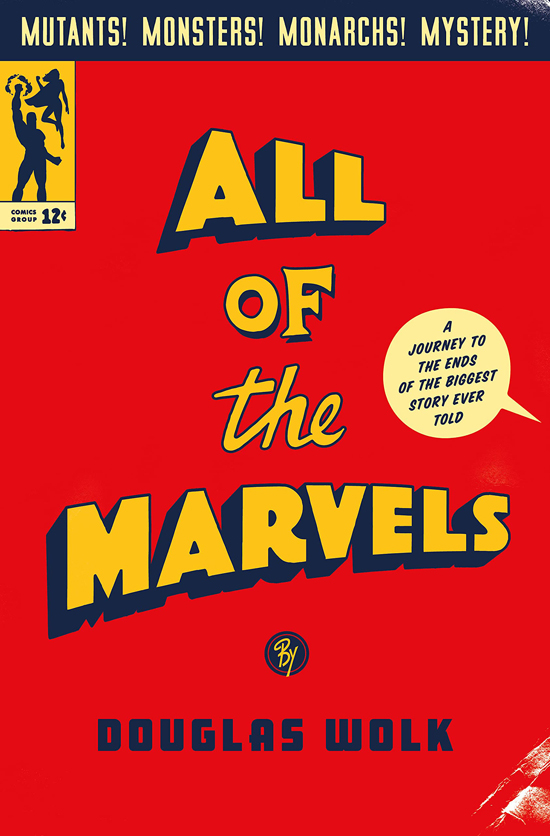

Globally available pop fictions and participatory media have given rise to a collaborative unconscious. Canons like Star Wars and Bond and Transformers and Fast & Furious are in a continual conversation with their followers, and comprise a kind of open-ended national epic of international capital. Where the deities and heroes of ancient lore directed the events of earth, our modern paragons’ destinies are determined by us. Not always directly or consciously, which is where All of the Marvels comes in. A journey from the hot core to the outer edges of Marvel Comics’ still-expanding universe, the book details how several generations have put particles of the mythos in place, and how the gravity of personal aesthetics and surrounding worldwide events have bent the path it follows and the shapes it took.

It’s a tale that author Douglas Wolk lived to tell after having read through some 27,000 issues of Marvel comics from the start of its march to worldwide cultural dominance in 1961, to roughly the present moment. It’s an oeuvre he circled like a mandala (one analog for the collective, converging artwork he sees the 60-year Marvel story to be), alighting on different eras and threading through the comics’ publication timeline to trace the more coherent patterns visible from afar. This affords him an analytical remove, but there is nothing like an academic remoteness; All of the Marvels is field research, from a native observer.

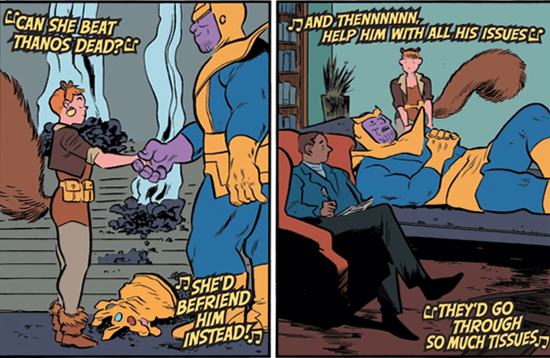

Subtitled “A Journey to the Ends of the Biggest Story Ever Told,” it is surely one of the greatest stories ever retold; Wolk, the most perceptive and imaginative of pop-culture critics, has a gift for interpretation that equals the most persuasive of evangelists, offering ways into the Marvel cosmology that can reassure the would-be devotee and compel the casual bystander. No better case for the eccentric legitimacy of ambitious, deceptively ephemeral culture has ever been made. Wolk starts with the visual metaphor of this cumulative story as a “Mountain of Marvels” to view for yourself and tell others about, a kind of biblical tower with a message everyone can make sense of. His initial descriptions remystify familiar characters to the stature of archetypes looming in our psyche or hiding in our inner childhood — you don’t have to know who either Doreen Green or Galactus are to be intrigued and awed by hearing of “a computer science student who can talk to squirrels and is friends with an immortal, planet-devouring god.” And like all meaningful lifetime disciplines (or even worthy casual pastimes), Wolk lays out lessons for living he’s divined from Marvel’s epic at the outset:

“Spending time in that world can make you better equipped to live in the real one: more curious about how its systems fit together; more willing to explore what you don’t yet understand, and accept that you can’t know everything; more open to hope in the face of catastrophe; more aware that no matter how overwhelming your own life may seem, it’s only part of a much bigger picture.”

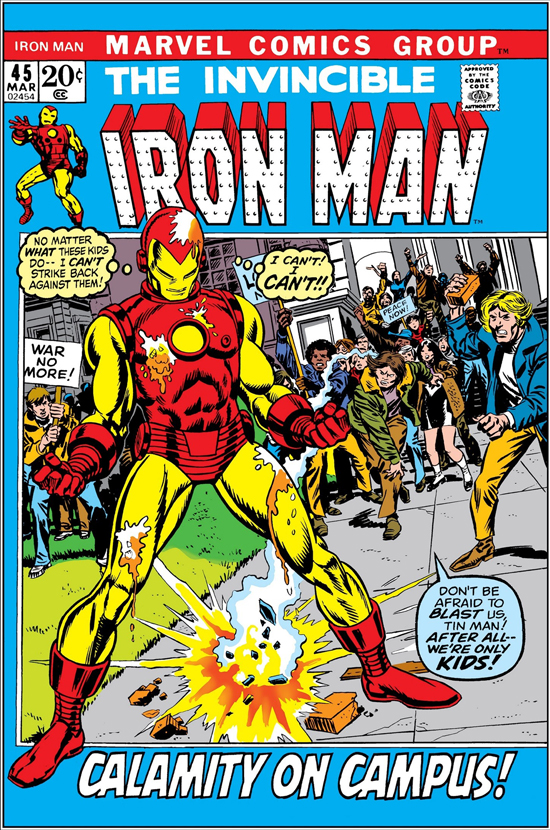

Wolk’s guided tour of Marvel spacetime orbits the major planets at length and briefly lands in fascinating shadows — interlude chapters take us to the pre-Marvel Universe world of 1950s kaiju who dominated the line before its post-humans started emerging (often as a result of the same nuclear mishaps that unleashed the giant monsters); examine the mark made on Marvel by the Vietnam War, whose real-life debates about perceived good and evil and the morality of force reflected on the comics’ already-ambiguous heroes while both college activists and GIs overseas were reading; and inventory the times that Marvel characters have become rock stars, and real-life presidents have become Marvel characters.

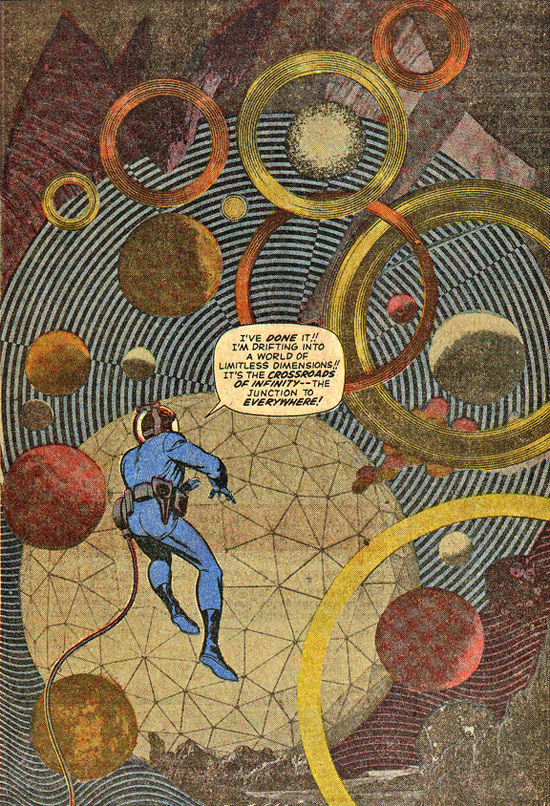

Wolk’s theme of an ever-expanding Marvel narrative is mirrored by the new discoveries he can make by diving deeply within it, with novel insights into the established storylines and themes of Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, Thor/Loki, X-Men, and Black Panther. These long-form chapters too have their significant surprises: Wolk’s tastes dovetail with prescience in a comprehensive remembrance of Shang-Chi in the comics (begun before news broke of the cinematic star that character now is); chapters are devoted to the linewide impact of a single idea (the mid-Aughts Dark Reign event, and how it seemed to eerily dramatize the Trump Era before the fact), or of a single creator’s method (Jonathan Hickman’s sprawling Avengers run, which scaled up Marvel’s omnibus team in every direction — planet- and cosmos-wide — and culminated in the collapse and reboot of the company’s whole universe). A final longer chapter is devoted to the next generation of both Marvel’s characters and readers, with an early draft of history centered on Ms. Marvel and Squirrel Girl, the sublime and ridiculous of a shared universe finally expanding to share creative power with a fuller spectrum of cultural and stylistic voices.

Blessed with a brilliant and elegant analytical mind yet trained in the immediacy of the commercial periodical world, Wolk produces the only work of comics scholarship I’m aware of that doesn’t operate at a delay of years or decades; the academic discipline relies on limitation of its samples, but full comprehension of mass narratives requires calibration to real-time consumption, and Wolk possesses both the enthusiasm and the perception to adapt his observations as his subject is in mid-morph.

This talent keeps his study open-ended while feeling in no way inconclusive. All of the Marvels is the snapshot of a place the size of a universe, at a single moment of infinity; it will reward a look for lifetimes to come, while saving the space for everything that fills the next frame.

Some stories we wonder if we’ll ever see the start of, let alone the outcome. The audio drama Give Me Away just concluded its first season, after a whiteknuckle existential cliffhanger at the end of its fourth episode and a subsequent hiatus. It’s the closest we still may get to knowing how the plotline of humanity’s first contact with extraterrestrial intelligence will play out. The effect of real-time on entertainment consumption is a rare enough phenomenon to observe these days; the season-finale episode 9 went up on Oct 15 and will hang in the air like an interrupted breaking-news update to the biting of many nails.

The experience of hearing episode 5, though, made different and just as effective use of the factor of time passed and suspended. It takes several minutes in to fully realize that this installment starts before episode 1; until and even after that, the lurch in sequence and the disruption of an equilibrium the listener has gotten used to serve as a great function-follows-form device to disorient the audience in the same way the story’s displaced aliens are feeling too. We’re at the Nevada-based compound where a mysterious ship has crashed, empty but filled with ghostly screams, which turn out to be thousands of consciousnesses imprisoned in a “penitentiary mainframe”; dissidents who were trapped there by the tyrants of their world. (Jesus’ temptation; the A-Bomb tests which poisoned whole towns; supposed alien landings and Area 51; it all happens in deserts, the tabula rasa of our tenacious sense of possibility and the sins we think we erase.) A handful of human volunteers are each hosting a refugee’s mind in their own brain, and the complexities of altruism and antagonism when the person you’re “saving” is forced to walk 50 years in your shoes are proliferating fascinatingly. So too is the strange uncertainty of who is pulling whose strings, as suspiciously specific personalities get extracted (so far, all of them principals in the alien resistance, albeit from different factions, with their frictions intact).

The verisimilitude with which playwright Mac Rogers renders inconceivable situations is astounding, even as it feels natural and inevitable; the divided psyches and loyalties of the ensemble, especially Sean Williams as the gentle/cynical Graham/Joshua, Lori Elizabeth Parquet as the benevolent/calculating Brooke/Deirdre, and Hennessy Winkler as the damaged/valiant Corey/Isaiah, create dramatic tension of a Dr. Strangelove or Andromeda Strain caliber. The very real stakes of an escalating fictional conflict, staged at the crash-site camp and reaching into suburban homes and so far only semi-seen corridors and chambers of power, invest us heavily in what’s next and what we may not have known all along. The future chapters are worth waiting for, but as in so many cases these days, we wonder how soon we really want them to come.

Then there are the stories whose breaks may never mend. By the time philosopher-cartoonist Dean Haspiel’s The Red Hook saga resumes, the titular protagonist has retired his costumed persona, in the coda to his longrunning webcomic, PTSD: Post-Traumatic Superhero Disorder (currently in-progress at Webtoon). He’s tried to put an end to one chapter of his life, while his mom, psychotic vigilante The Coney, keeps leaping backward into an epic she could walk away from. Pieces are put back together out of sequence and with gaps; the painful memory of half of their family getting gunned down in mob-hit crossfire, and the cracks this put in the two survivors’ lives together and apart, recurs like a migraine on a treadmill, small details sharding off of it over time. Haspiel himself has fought for and helped forge a future for individualistic hardboiled-charm comics, and his alter-ego here is trying to stride forward while the Coney’s truest sickness is the attachment to old ways, obsolete stories. Sam Brosia (the former Red Hook) has stepped outside the box (panel) entirely; the strip’s short leap forward in time finds his allies The Possum and Sun Kiss (each, like him, former criminals who switched teams) now standing larger in the frame. This lesbian, Latinx-Asian couple are heroes who look and act like the future, while Sam seeks to be content tending bar at a beloved local dive, a dying way more worth living for than his past occupations as boxer, burglar, and accidental hero. Haspiel’s dialogue dances like a prizefighter and his visuals are the very shape and color of tenderhearted toughness; rough-hewn and expressive, scruffy and dynamic. Tautly tangled circumstances may pull Sam back in several directions… but for this character and creator, there’s no end, just another edge.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE