Norbiton (36)

By:

August 6, 2021

Anatomy of Norbiton: Spatial

“…the cloister, Hugh [de Fouillory] says, should be a perfect square, like the atrium of Ezekiel’s temple, in order to express the measure and equanimity of the monastic life and to anticipate the perfection of the divine.”

Terry Comito, The Idea of the Garden in the Renaissance, p. 45

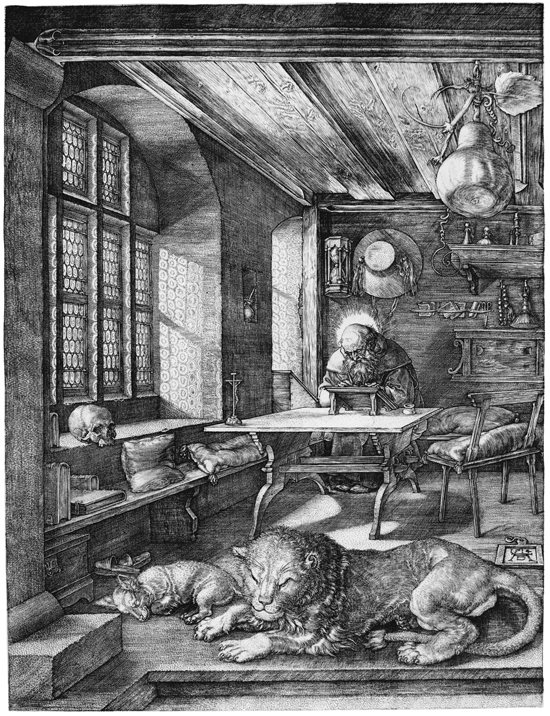

– ST. JEROME IN HIS STUDY

VINCENZO CATENA

The basic spatial unit of any city is the interior, but an interior space is always in danger of collapsing in on itself: it requires the backbone of a proper desk. And NORBITON: IDEAL CITY is nothing if not a city of desks.

A desk is not a sacred object. It is not made of holy wood, a World-Ash or Tree of Life. There is no spirit inherent to the object, it has no soul, is not a sluice of energies. It is rectangle upon which I set my elbows, nothing more.

Nor is setting your elbows a confession of faith. It is merely a pragmatic advance into and across a space which lies easily within our sphere of possession. You set your elbows on your desk while you drink your tea, or type on your laptop, or hold open a difficult book, a book wanting study and notes. To your left and right are piles of paper or other books or things you occasionally need to use—inkwell, scissors, bell, skull, hourglass, armillary sphere, cowrie shell, emblematic vegetable, lion, partridge, peacock, &etc. You can swap these objects in under your attention, in the tripod formed by your elbows and your head. These are the uses of a desk.

Being a vertical species, I suppose, we want flat surfaces over which to operate, be it a meadow to mow or a street to cross or a stage to strut on; a workbench or a kitchen counter or an operating table. Or a desk. Set a desk in front of someone and they have a miniature spatial field on which they can tinker with the World.

There are those who set their desks to face the wall, and those, more presidential, who set their desks to face into a room.

My desks have always been set under windows, my back to the cave, my face directed to the outside.

Civ Clarke, who for months has been sleeping and living on my sofa, always there behind me as I work, but who is now leaving for his own flat, his own desk, his own structured phenospace, tells me that he has experimented at various times with oblique desks, desks starting out from windows into rooms, desks on balconies, miniature desks you can lay like supper tables over your legs as you lie in bed. Erasmus Darwin reputedly had a demi-moon cut out of his dinner table to accommodate his belly, and Clarke has given that serious consideration too.

– ERASMUS DARWIN

JOSEPH WRIGHT OF DERBY

But, he says, there is no correct solution to any given space since a truly disciplined mind would need no desk at all. It would move freely in mental space, needing no pen, no blank empty paper on which to type or write, no orthogonal planar support.

Clarke does not have such a mind. Neither do I.

We may be a vertical species, but we have a certain rotational potential. Representations of St. Jerome in the wilderness cast the saint adrift in a non-linear space, a chaos of rocks and trees. Wilderness-Space is an unmeasured body of air, not a civic grid.

So while some artists insist on reasserting the vertical-horizontal axes of the kneeling saint and his crucifix, Leonardo da Vinci, who worried about these things, allows Jerome to bunch and crane and contort himself, give himself over to wholehearted anatomical distortion.

– ST. JEROME

LEONARDO DA VINCI

Here is a body in the open, we understand, albeit an open girt with sinuous lion. And the body, buoyed in empty space, is therefore grown strange, evolving new cartilaginous support as though all that internal pressure of soul, straining to vent, required newly improvised exo-skeletal procedures.

The wholly spiritual, undesked individual, to repeat, does not need page, flat surface, or vertical flickering, dancing pen.

St. Jerome, however, oscillates between wilderness and study. He made the Latin Bible, wrote commentaries on the Gospels, he corresponded with Church fathers. He needed a desk.

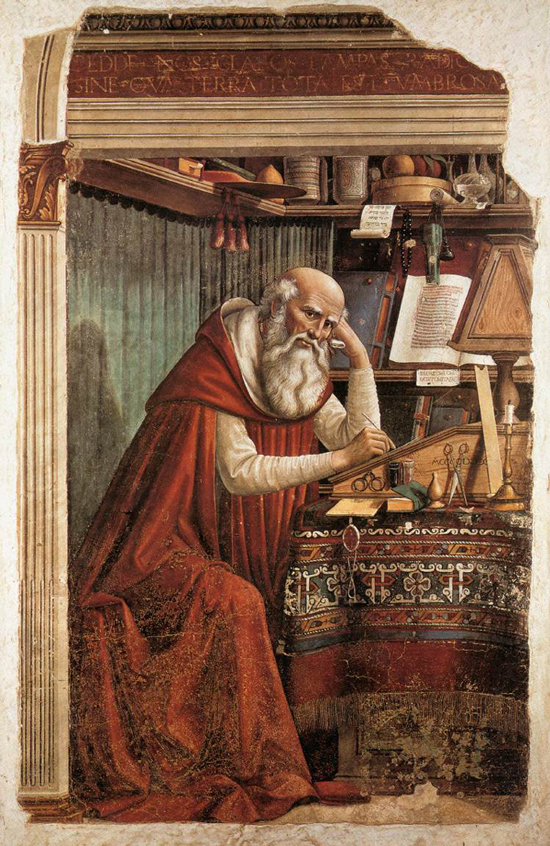

– ST. JEROME

ALBRECHT DÜRER

And there is such a thing after all as discipline and the channelling of spiritual energy, should you be graced with a surplus.

Jerome has not a surplus but a glut. Here it flows out through the old man’s finger tips, under his nose; he does not lean like a farmer on his elbows but delicately, along the length of his forearms as they settle along his little lectern, a disputed, queried horizontal. Under the desk his toes mimic his fingers. He is all thought, all Latin Vulgate.

The desk is set obliquely to the window but the window is not a viewing port. It a source of diffused light, light that is functional, not spiritual, light in which you think, not feel, light in which you reach for your functional objects—the inkpot, the scissors, the cardinal’s hat, the velum books, the unplumped cushions—as required, or, suspended between words that wait to come, contemplate your emblematic objects—the sleeping dog, the vigilant lion, the gormless skull, the fragile crucifix.

Over Jerome’s head swings a prize-winning gourd.

The gourd is an emblem of Resurrection, associated with Jonah and God’s mercy at Nineveh[1] , but here in Jerome’s study it is swollen, palpable, alien, invasive.

Jerome studiously ignores it. It had been a matter of dispute between Jerome and St. Augustine whether the plant referenced in the Book of Jonah was indeed a gourd or some sort of ivy. Jerome had gone with ivy in his commentaries, and wrote (a little tetchily) to Augustine of the matter.

I have already given a sufficient answer to this in my commentary on Jonah. At present, I deem it enough to say that in that passage, where the Septuagint has gourd, and Aquila and the others have rendered the word ivy (κίσσος), the Hebrew manuscript has ciceion, which is in the Syriac tongue, as now spoken, ciceia. It is a kind of shrub having large leaves like a vine, and when planted it quickly springs up to the size of a small tree, standing upright by its own stem, without requiring any support of canes or poles, as both gourds and ivy do. If, therefore, in translating word for word, I had put the word ciceia, no one would know what it meant; if I had used the word gourd, I would have said what is not found in the Hebrew. I therefore put down ivy, that I might not differ from all other translators.”

Letter from Jerome to Augustine AD 404

So that is that. The scholar has spoken. But the man is still plagued, like a prophet, by the ludicrous object. I am what I am, says the gourd. Jerome will, in time, have to revert to the wilderness, to exorcise this gourd in a space that is become itself all bellying gourd.

But for now he is at his desk. I am not. Civ Clarke and I are in fact pulsing between two desks in a discrete packet of space.

We are sat in the cab of Old Sol’s Mark V Ford Transit, Clarke’s handful of belongings (some charred, some new) collected in a cardboard box which he balances on his knees, the van more an emblem of translocation than a vehicle of it. But for the solitary object we carry in the back, we could very easily have walked down the Cambridge Road, since Clarke is returning to the Cambridge Estate.

As it happens this morning the van moves at walking pace, or something less than walking pace. That our progress is sepulchral is not an index to our spirits, which are light on the whole; but an index to the traffic, which is not. The traffic stutters, held back by temporary lights and road-works and lorries unloading; by a convolved, systemic malaise.

The cab however is spacious. In most models of the Mark V Transit there is a bench seat for two passengers, but Sol’s van is ex-British Telecom, and the BT fleet went with a pair of single seats; this missing third seat lends the interior a roomy, well-breathed quality, a salutary absence. There is no third that sits always beside us. There is just Clarke and me, in relaxed proximity.

There is also a bulkhead between the cab and the body of the van; we are insulated both from the van’s near-empty cavernous rattle and from the street outside.

I am explaining to Clarke, to the best of my ability, how in neurological terms space is a continual invention. Known space—in this case, known Norbiton—is mapped point-for-point in physical networks across our brains; as we move through actual space, neurons fire in sequence, a system of cerebral illuminations. It is the firing of a given neuron which positions us. Thus we do not have in our heads a map so much as a destination and a sequence of recognitions; we know what to do at each junction as we come to it. We know where we are going as we get there. Destination and journey are, experientially, collapsed. Step by step, the little lights go on and off in our heads.

It just happens that now, stuck in traffic, all our positional lights are off. We are momentarily adrift.

Is my desk, I wonder aloud, likewise mapped to a tiny network in my brain? It makes sense to me. The desk is a rectangle that is set in a room not perfectly square. There are objects on it which do not move much—fixed co-ordinates of lamp, laptop, globe—and objects which flicker over its surface[2] . Sometimes there is a cup of tea, sometimes not. Sometimes a pile of books, sometimes not. Biscuits come and go.

– ST. JEROME

DOMENICO GHIRLANDAIO

The arrangement of these objects feels right or not, day to day. Marsilio Ficino would have seen the assembly and arrangement of objects as the right channelling and concentrating of astral effluvia. Open and close the logic gates in the correct sequence and such intangibles as thought can be made to flow or pool, to make intelligible patterns.

But I prefer to think of my physical, spatial systems as mapped inward, into some epitome of order still smaller than the room itself; a tiny signature of the room and the desk and their contents—myself, I suppose, included—written into the cellular matter of my brain. Thus the desk will accord at any given time, more or less nearly, with the (unstable, potential) mental image I have of it. I will be properly located at it, or lost within it.

And I can take steps to align one with the other. This is what I understand by tidying my desk. What is mess, after all, if not an accumulation, an unspooling, of raw data?

We nudge forward through the chaos of compacted street-events, and a solitary neuron fires.

Civ Clarke, who has given no visible sign of thought (in spite of the clarification of the idea of desk I have offered him), now claims to think of space not as so many contiguous vesicles which he is ‘in’, but as a system of surfaces among which and around which he moves, and on which he carves invisible or mental prison runes, sigils and arrows, a tramp code notched on gateposts; if he does not come back that way, he says, the signs will never be reactivated, and will in time smooth to nothing.

When he dies, not only the signs but the whole system of space and all spatial relations will be erased. A private language will be lost.

I wonder to myself what mental hobo signs he has scrawled on my sofa, and what he’s reading off now, along this street, what incising, editing, adumbrating is going on in that pale pate of his. If what he says is true, we are continually writing commentaries to known space.

Take this street, a traffic not only of cars and vans and workmen and pedestrians and cyclists, but a congested inter-traffic of the mind. We are atrophied in procession. A procession is how a civic body anatomises itself; it strings its body out from time to time along a length of street in floating discontinuities, each available for examination.

– PARTHENON, WEST FRIEZE

What do we see here then? Like a Brezhnev parade, there is a cyclical, endless quality to it; unlike a Brezhnev parade, it is Brownian, contradictory, mildly carnivalesque. Drivers are cursing silently behind glass, smoking out of windows, pedestrians are cutting errant trajectories across and between cars, a cyclist in a tight knit of apparel and shoes like clogs is hobbling his bicycle along the pavement. A thoroughfare then, life channelled and bunched, the slightly rabid, very ragged body politic exposed to the sky. No individual is wholly remarkable; nor is anyone wholly unremarkable.

Space may have for each of us its private wireframe configuration, but others make different use of the same space, tramp over it, distort its grid. We are not alone. Our space is not just shared: it is continually written over.

The implications of what I am telling Clarke about his neurons are various.

For one thing, distance and separation do not exist unless we activate the path between two points; they can, in certain imaginative states, collapse to nothing, or almost nothing. Absence can be eliminated. Thus St. Jerome, dying in Bethlehem, could simultaneously open the shutters and stir the air in a room in Hippo, and speak to St. Augustine, which might offend our understanding of physical reality, but not offend our spatial imagination.

And if absence can be eliminated, so can confinement. Sit sufficiently long in one place and your neuronal map will fade. Sit at your desk and stare from your window at the World-in-Tremulous-Flux that lies without, and other, latent maps will emerge, other mental progresses will be activated; whether of memory, or affection, or projection; you will be everywhere, because you are nowhere in particular; you will be at large in the wide World, because you are lodged deep in the belly of Norbiton.

– ST. JEROME IN HIS STUDY

JOOS VAN CLEVE

Thus we stand, or sit, or dwell, each in our cell, and the flickering patterns subside. At rest we collapse to a point or a plane, a tripod of elbows on a desk.

Here for instance is a tripodal St. Augustine, as represented by Vittore Carpaccio.

– ST. AUGUSTINE

VITTORE CARPACCIO

He is depicted in the act of receiving the news of Jerome’s death from Jerome himself[3] , a disembodied voice not of consolation, or revelation, but of admonition:

“Augustine, Augustine, what are you seeking? Do you think that you can put the whole sea in a little vase? Enclose the world in a small fist? Make fast the heavens so that they may not keep going in their accustomed motion? Will your eye see what the eye of no man can see? Your ear hear what is received by no ear through sound?… What will be an end to an infinite thing? By what measure will you measure the immense?”

Surprising that, in this sort of mood, he had nothing to add about the gourd; but Augustine listens attentively in his undimensioned room.

Undimensioned? For a room drawn according to the conventions of linear perspective, this is a curiously flat space. The ceiling is too truncated to give the eye much information; the recession of the long wall is interrupted by the windows that are not windows but strips of light; the rear wall is a series of schematic openings, both the rear room to the left and the underneath of the altar revealing not volumes of space but a picturesque jumble of shapes, as though the lumber of his mind were momentarily reduced to a two-dimensional lattice.

– ST. AUGUSTINE (DETAIL)

VITTORE CARPACCIO

The books on the shelf along the shortened left wall are ranged obliquely, quite as though they were only pictures of books; there are sheets of music and a letter bearing the artist’s signature which are held to the picture plane as though pressed to a window; the desk is not a projection in space but a severe horizontal line.

Augustine and Jerome are not synapses at either end of a cosmological nerve, or two boys playing tin can telephone down the taut existential wires of the ancient Christian world. They are one and the same, evidence of a violent collapse. This, we intuit, is what the news of a death will do: collapse everything, like a theatre set belonging to a play that has reached the end of its run. Whatever or wherever Jerome is now, it is a place without dimension or extension or volume or relation. If he has, in the words of Auden, become his admirers, then his admirers—specifically, Augustine—are no longer quite what they once were, either.

– ST. AUGUSTINE (PREPARATORY SKETCH)

VITTORE CARPACCIO

In time we get clear of the traffic and pull up beneath the Madingley Tower. It is the same tower on the Cambridge Estate where Clarke lived previously.

We have in the back of the van a solitary piece of furniture, a simple wooden table that will serve Clarke as a desk in his new flat.

Clarke carries his box of belongings up in the lift, then comes back down to help with the desk. We walk it up ten flights of stairs. It is not heavy or particularly long (about the length of my outstretched arms; wide the length of one arm from shoulder to finger-tip). But it is no longer a desk: it is an awkward manifold of vertices, edges, angles, dimensional relations; the table tips and skews in a complex if predictable jolting spiral, its legs not legs but orthogonal projections generating interference with the banister and hand rail which are not a banister and hand rail but a helical proposition. For a few minutes, in order to cope with this new object, our minds are forced to run reams of Euclidean code.

We get the table into the room it is intended for and set it down, breathing hard, and it is suddenly a horizontal plane, a wholly different object now: a desk in an empty room. Clarke brings a chair in from the kitchen and clatters it down in front and sits on it and tries the space, the relation of chair to desk to window to room, and finds it to his satisfaction. He can see out of the window, across the rooftops. He can begin to think.

And yet in spite of what Clarke seems to think, sitting there, one forearm across the empty desk, nodding, contemplating tea and work and the foundation of empires of thought, this is not his space. Not his alone. Whatever space we clear for ourselves, however many blank sheets, empty desks, virgin wildernesses we propose to ourselves, innumerable invisible presences have already marked it out. There is no street that has not been dug up, walked down; no seabed that has not been scuttled across. The World, to use Clarke’s formulation, is all fading tramp codes.

Augustine sits in his collapsible study and his thoughts range over infinities or lexicographical niceties. To his right a small white dog, wholly volume on the empty plane of the sand-coloured floor, looks up at him, quick with intelligence. In Augustine’s head the voice of Jerome is counting off offences on its dimensionless fingers, but in the room where the dog is there is only the movement of air, patterns of attention.

– ST. AUGUSTINE (DETAIL)

VITTORE CARPACCIO

What is Carpaccio representing here if not a vision of mental escape? St. Augustine has not set his desk to face the window, but he is nonetheless staring out of it. A window is a picture plane, as much as the picture plane in linear perspective is a window. Both are objects of contemplation, and contemplation is, to repeat, a form of escape. All cultures, all times have their version of it, their dream of unconfined space, an ecstasy in this case reached through monastic confinement, scholarly rigour, and the dislocations of death.

Like Jerome, I always had a hankering for the wilderness. Who doesn’t, at a certain age? Or at any age. To set off obliquely across fields—this is me, sitting in a ground-floor classroom at school, in a history lesson, aged seventeen, but it could be anyone, anywhere, looking from any window—oblique, which is to say, not respecting even the boundaries of the fields that have emerged over centuries of inter-generational thought; set off in a straight line in any direction, crossing fields, crossing oceans, finishing only at the ends of the earth—Patagonia, Kamchatka, Unalaska. Somewhere.

To walk in a place, in other words, to which no neuron is mapped, neither mine nor anybody else’s. But even in such a place there would be birds and mammals with their overlapping neuronal maps; and there would be Jerome, impervious to time and space and clunking neurons which to him must seem like thermionic valves slowly glowing, chastising me from out of the blue because I would close the infinite in the nutshell of my head.

In the end, aged 17, I went nowhere to speak of. I just sat on in my history class until the bell went. Thus it goes. You sit in the small room where you work, a room organised with bookshelves and a desk; a tight, compacted space like a ship’s cabin, everything to hand, more or less, everything stowed, functional, gleaming; a room in which to think is to rap your knuckles on sound oak; and you look from the window as though at gently pitching oceans, as though you were always moving; always in motion, motion towards or motion away from; always unconfined.

Footnotes ☞

1 “So Jonah went out of the city, and sat on the east side of the city, and there made him a booth, and sat under it in the shadow, till he might see what would become of the city.

“And the LORD God prepared a gourd, and made it to come up over Jonah, that it might be a shadow over his head, to deliver him from his grief. So Jonah was exceeding glad of the gourd.”

Jonah 4:5-6 ⏎

2 Flicker, that is, on a cosmological time scale – their movement is in fact rather sluggish. ⏎

3 The story of the Vision is derived from apocryphal letters, dating from the end of the 13th century, which were variously ascribed to St. Eusebius of Cremona, Augustine himself, and St. Cyril of Jerusalem. Various versions of the letters frequently pop up attached to incunabula accounts of Jerome’s life. ⏎

Anatomy of Norbiton on HILOBROW

Original post at Anatomy of Norbiton: Spatial

Anatomy of Norbiton

Short Life in a Strange World by Toby Ferris

Toby Ferris on Twitter

On the Paintings of Pieter Bruegel by Toby Ferris

All tapir illustrations by Anna Keen: portfolio