Norbiton (35)

By:

July 30, 2021

Anatomy of Norbiton: Sartorial

“Every fashion couples the living body to the inorganic world.”

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, [B9,1]

– DRAPERY STUDY FOR THE RISEN CHRIST

GIOVANNI ANTONIO BOLTRAFFIO

I am trying on my ghost suit.

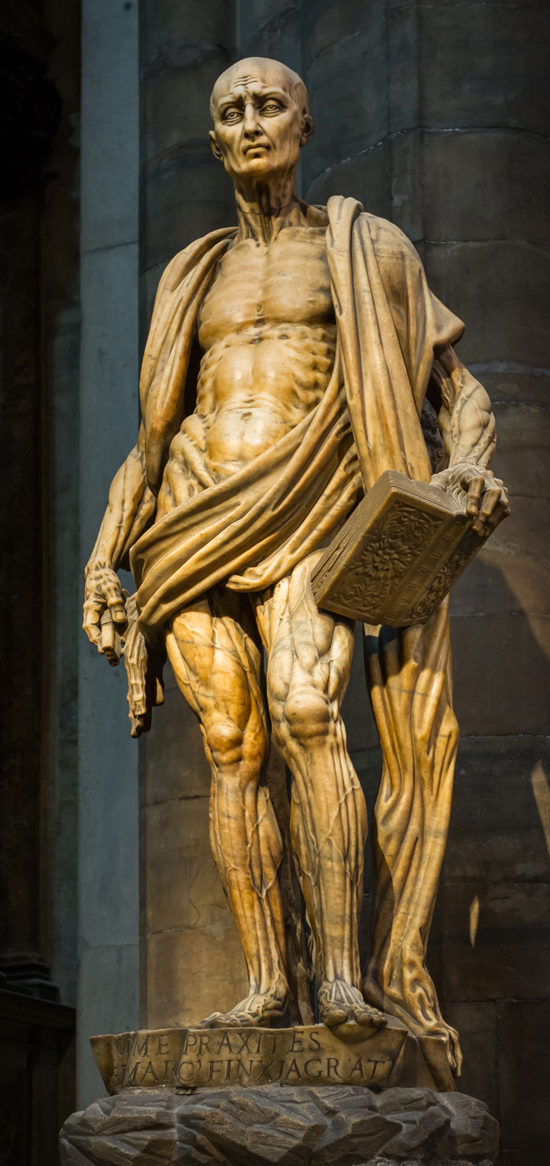

My ghost suit has hung disembodied in my wardrobe for several years—since the day, in fact, I quit my job, demobilising myself from the World—a sagging Bartholomew of lost purpose and ambition.

– BARTHOLOMEW FLAYED

MARCO D’AGRATE

It was not a cheap suit. It is greyish-blue with a cream lining and still in good condition. But it is several years old now, and when I try it on something is not right; there is something about the cut which distinguishes it as, very subtly, not of this time. We are accustomed to the drift of fashions expressed as a progress of museum mannequins: hose and doublet to suit and tie, monk’s habit to fur-trimmed cloak, Indian sandal to Turkish slipper; but these are broad categories, into one of which I and my clothes still no doubt fall. But this suit has slept too long. Where once I clung to the continental edge of taste, here in my suit in front of my mirror I have woken to find myself standing ankle-deep in the encroaching ocean of past styles, other times.

This is the suit I would wear now if I were interviewed for a job, or getting married, or awaiting burial. The world and its graveyards are filled with such suits—dated, shiny at the elbows, cut to a different age, each imperceptibly adrift, bobbing away on the waters of time.

The Renaissance deduced its saints and gods, its celestial virgins and allegorical figures, from the outside in, beginning with the evidence of their clothes, the study of their drapery, deriving the contours of empty spirit from calligraphic textile[1] .

– DRAPERY STUDY

LORENZO DI CREDI

This is, after all, how God created the world, the shapelessness of created matter plastered over with earth and waters and sky, adorned with the cosmetic gratuity of trees and fish and animals. The invisible is not made visible, precisely; rather it is implied: angels and demi-gods may be clothed in flesh-like opacities, but these are tokens of spirit, so much script in a legible universe.

Painters however, unlike God, know that there is nothing prior to our material selves, no stable wireframe matrix underlying the unrolling and draping of bolts of unformed cloth. It is one of their tricks. There is no over and under; there are only assembled components of a whole. The arm, the head, the hand, the sandalled foot lie contiguous to the cloth, not functionally behind it, or under it or beyond it. In a painting, we are adjuncts to our clothes.

There is nothing mystical here. It is only a technical address, a stock-in-trade. Painters draped small dolls with waxed and pliable cloth, posed them, observed them, copied them[2] . As apprentices, they learnt to fashion a cloak as a chef would learn to make a sauce; there was a recipe. The sauce might imply a duck, as a cloak might imply a risen Christ; but for now both duck and Christ were absent, mere pencilled coordinates on a menu, a chart of psychic possibilities.

There is likewise a systematic, technical address underlying the rendering of cloth in paint in the trecento, the quattrocento.

The paint was applied along a three-tone axis. The shaded valleys of the cloak, for instance, would be painted in the desired hue; the sloped valley sides in that same hue mixed with white in equal measure; and the highlights in one part hue to two parts white. For lighter hues, the shadow would be painted in hue mixed with black, and the highlights in hue plus white.

And for certain compound hues, green, for instance, painters followed a convention of splitting the colour into its darker and lighter elements—so, blue for the shadow and yellow for the highlights—as though their work of modelling did not so much create an illusion as reveal the structure of the visible world.

A structure, as it happens, of dyed cloth, or of mixed paint.

– DELIVERY OF THE KEYS (DETAIL)

PIETRO PERUGINO

Painted saints wear cloaks to distinguish their sacred and ancient souls. The cloaks are one of their attributes, like halos, eyes on dishes, towers, gridirons, fish. They are at once monkish and classical, massive, dignified, and material.

Next to them, the costumes of contemporary Florentines or Romans seem adapted not for thought but for free movement. The non-saints in Perugino’s Delivery of the Keys are city dwellers, after all, merchants and bankers, not prophets.

– DELIVERY OF THE KEYS

PIETRO PERUGINO

These are clothes tailored for rapidity. The apprentices in the background, apparently hopping and gyrating and dancing (but in fact cheerfully stoning a tiny Christ as they might set fire to a cat) are free to move, unlike Peter with his immense keys. An apprentice wishes above all to be untrammelled, because he is learning that he is nothing of the sort.

– DELIVERY OF THE KEYS (DETAIL)

PIETRO PERUGINO

The clothes of a saint emerge, a property and index of his soul; the merchant’s or the apprentice’s are a practical response to the exigencies of the world around them. They choose their clothes, and, in this sublunary world, they can change them. There are such things as wardrobes, tailors, changing rooms.

And an architect? To the extreme right of the foreground group, two architects, perhaps those responsible for the Solomon’s Temple which dominates the background and controls the perspective scheme of the whole fresco, are locked in discussion. What do they wear? Something between a merchant’s silks, and a prophets drapery. While an architect might once have been unencumbered like those new-formed apprentices, he now aspires to the oracular, a force for elemental change in the city.

– DELIVERY OF THE KEYS (DETAIL)

PIETRO PERUGINO

Veronica de Viggiani, architect, stands behind me and appraises the cut of my suit. Then she takes some pins and fiddles with the looseness of the cut, the sag of the trouser, the mouldlessness of the jacket. This suit, she says brow furrowed, never fit; it has nothing to do with the passage of time.

She is possibly right. She has a critical eye. An architect’s eye. Do architects know clothes? I do not know, it seems plausible. Frank Gehry says somewhere that a building in the end is a system of surfaces, and so, I suppose loosely, is a suit of clothes. A system of surfaces.

Whatever de Viggiani does with the pins quickly works; I feel myself pulled provisionally into shape under her nimble fingers. As she goes about her business, pins in mouth, I describe for her the structure of the Florentine textile industry, the shift in gravity over the centuries from wool to silk, the division of labour between the more skilled and better paid artisanal labour in luxury crafts (men) and the spinning and weaving of textiles (women); the women spinning, spinning, endlessly spinning[3] , through the city and out in the contado; the men, artful tailors of the Public World, chalking and scissoring the black Spanish cloth, attired with precision, with intimidating neatness, exercising a bravura craft of self-assured, urbane gestures.

– IL TAGLIAPANNI

GIOVANNI BATTISTA MORONI

The tropes of mythical female craftwork are familiar—Clotho, first of the Moirai, spinning the threads of fate from distaff to spindle for Lachesis to measure and Atropos to cut; Ariadne unspooling the umbilical twine that leads Theseus from the labyrinth; Philomena weaving the names of her assailants implacably into the cloth. They imply a perpetual curation, a gradual forming, of the world. Men take scissors or swords and slice the world roughly into a congenial shape. Women allow it to flow through their fingers. Which is why Penelope’s nightly unweaving is so destabilising to her suitors, such an adept sidestep.

The fabric of the Florentine Renaissance, I conclude broadly, the continuous membrane of cloth that underlies everything and informs everything, however it might subsequently have been chopped and sewn, was created and held in place by the flow of female labour. Men dress up like prophets or dandies; women are relentlessly occupied in the factory of the soul.

– LAS HILANDERAS

DIEGO VELÁZQUEZ

Veronica, standing up now, her mouth free of pins, wonders aptly enough how she went from architect to Norn in the course of a couple of rambling paragraphs of thought, and she is right. I stand here in my nipped-in suit, foolishly dominating the public square of intellect as men—saint or architect, bravo or apprentice—dominate the public square of Perugino’s keys.

Michelangelo described Perugino as goffo nel’arte, and I recognise that I, too, am sometimes goffo—clumsy—in thought. My thought is all surfaces, layer piled upon layer[4] ; not an investiture of spirit but a giddy, toppling, poorly-founded accumulation. Proper thought, like a proper wardrobe, is nothing of the sort. Proper thought consists of interchangeable materials, mannequins and chalk and tape-measures. Not a stuffy moth-eaten pile in a dressing-up box[5] .

The stuff of thought, like clothes but unlike, say, books on a shelf, notes in a notebook, or data on a spreadsheet, does not accumulate in our lives. It is the opposite of an accumulation. Just as individual items of clothes—a coat, a pair of trousers, a shirt—overlap in time, scuff, fade, are repaired or replaced, are recombined in new habits, making of you a mannequin ship-of-Theseus, bobbing about in time; so too do ideas have their time, enjoy a half-life, a non-uniform rate of decay.

Unless that is you refuse to throw out what you will never wear again and have sartorial (and ultimately intellectual) categories such as ‘around the house’ or ‘for hacking about in the garden’; a bottomless repository of defunct sartorial thinking, of tatterdemalion, scarecrow intellect.

Unless, in other words, you write it all down.

Do we exist inside or outside our clothes? It is a point of ambiguity.

We are concealed by them, our bodies awkwardly or gracefully inhabit them; but our sensory arrays lie, in general, outside them. There are exceptions—a burkha’d female, a cowled monk, a helmeted soldier, retreat inside their clothes; but for the most part our heads emerge from among the folds and layers of cloth and gaze down upon our own exteriors. We are left to guess as much as anyone what is happening in the opacity within, down in the shrouded interior.

Nor does nakedness reveal the truth of the matter. Undressed, we do not revert, but enter a fresh state of being, a sort of private shapelessness. Naked and alone, not running up against others in the public realm, we lose definition in proportion as we gain breadth and freedom. We are not, in other words, naked under our clothes, but translated.

Veronica de Viggiani has had me take off the suit and stand there in my boxers and shirt and socks. She wants to examine the lining and the trousers, the better to pin the hem. This suit, she seems to think, might be made to accord with the present times with a little trimming of lines, a little alteration.

I stand there doubtfully. These are my smalls, I announce in dumb-show to the room, the flimsy endoskeleton of my whole persona; look on my threadbare soul, the fading patchy fabric of my heart. And weep.

Veronica does not weep, seems not to notice. She has seen me in various states of undress before. To repeat, in removing articles of clothing, I am not revealing some deeper truth but framing a series of new propositions, the validity and soundness (not to mention the hilarity and offensiveness) of which my lover will now test; we work, in shedding layers, not towards truth, but towards an intimate construct.

On the outside of the Orsanmichele, the great cult building of Renaissance Florence, Andrea del Verrocchio provided for the universitas mercatorum, or Mercanzia[6] , a representation of St. Thomas satisfying his doubt by penetrating, layer after layer, the cloth and then the flesh of Christ.

– CHRIST AND ST. THOMAS

ANTONIO DEL VERROCCHIO

But there are no layers: Christ, in pulling back his cloak, produces new material, new bronze in this case, where, clothed, no bronze would otherwise have been. This is not revelation, but creation. The question supplies, if not the shape, then certainly the fact of its own answer.

Thomas, according to the appropriately apocryphal Acts of Thomas, was the twin of Christ, the yin to his yang, the earth to his air; the doubt to his indubitability. Verrocchio has made of him a complexity of furrowed cloth (and are those Indian sandals?) next to the sculptural assurance of the very material chain-clanking ghost-god.

Doubt, we are learning, is the corollary of certainty. Without doubt there is no inquiry, no hypothesis, no true economy of knowledge. This is not Peter, with his vast keys and putative gates, his adamantine rocks of dumb certainty; this is Thomas, flickering in and out of existence, in tandem with his putative déshabillé Christ.

To repeat, do we exist inside or outside our clothes? The answer is, neither, and both. We create for ourselves a habitable mid-zone. Clothes do not demark a precise boundary of inner and outer. We do not look down, tortoise-like, on representations of ourselves. They are not merely surfaces; neither are they containers within which we shiver and huddle. They are our route to the outside, a series of gated walls leading to the open hinterland of our phenotypical world.

Suits, for example, have linings. The lining is not inner—to get a glimpse of the lining is not to see the suit venting truth, the inner truth of the suit. The lining is meant to be seen, sometimes; it belongs in part on the outside.

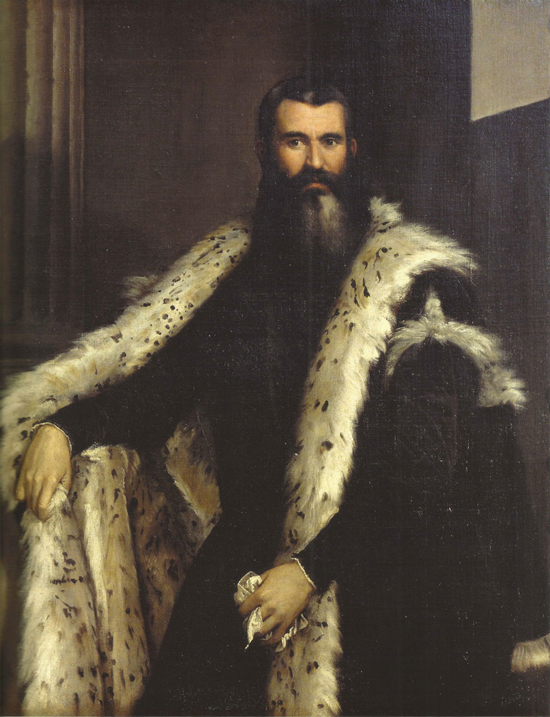

There is a portrait by Paolo Veronese, for example, of a Venetian gentleman who exults in his lining. The lining is of lynx fur, with a maculation the inverse of the sitter’s greying beard and hair, as though they had encountered one another at some mid-point of existence, the dead lynx and the living man.

– PORTRAIT OF A MAN

PAOLO VERONESE

The cloak is thrown open. But it is not an act of opening up. It is a distraction, a matador’s trick. The cloak is dazzling, full of soft angles, impenetrable folds. It is an object of power, dancing on the edge of sumptuary laws, armour for a commercial age. And it is not only luxury clothes that have this property. In the same way, the habit of a Franciscan monk is a deflection, an armature of the spirit. Wedded to the ideals of poverty, a Franciscan was responsible for the patching and mending of his own clothes. As he grew in spiritual maturity, so did his clothes grow in patchwork making-good, a badge of moral rank.

– ST. FRANCIS IN MEDITATION

FRANCISCO DE ZURBARÁN

His habit, in other words, was the outer perimeter of his resistance to the world. Like a schoolboy’s squint tie, our clothes mark out the limits of our acquiescence. We do not ghost through the world, however we might comply with its currents; we set down little drag anchors, seek out resistance. This is what it is to be alive, after all, whether in the spirit or in the flesh. Seeking resistance. Seeking out the resistant knots.

Thus while our monk is protesting the world of the flesh on the outside, resisting its buffets and blandishments, on the inside he feels the perpetual itch of his supremely coarse materials. And so too our lynx-furred man. Look at his right hand, immersed in the depth of fur, as though he were only part-emerged from his own clothes; clutching them as though he might otherwise float free of them, or sink beneath them. A man at ease in two worlds, but hesitant in that space between them. Hesitant, and fully existent.

Veronese himself was known to be alive to the allure of luxury clothes[7] , no doubt in part because they spoke to his gathering eminence, but in part perhaps also because luxury materials have a haptic weight. The painter lives, after all, in a broad and complex sensorium, one informed not only by the visual: paint is a substance, it is powders and oils, mixed and ground; the workshop is a noisy place, the staffage, the props and costumes, lie around, confusing the sense of place and time, of the appropriate.

So the layering of paint, the building up of thin surfaces, is more than a bit of visual trickery, a cleverness of the hand over the eye; it is nearer to brass-rubbing, or to archaeology, wherein a delicate touch, a systematic procedure, will reveal what lies there, all around us, not invisible—quite the opposite!—but latent; a latency of photons, let’s say, dancing in the middle air, masslessly lighting on a sensitive and exposed surface.

Thus the sitter sits, for hours, in an etiolated Bergsonian present. And an imprint of him or her emerges from the process, a material, stubbornly resistant knot in time. Paintings, like the sitters they represent, are fields of mild resistance. In the words of Veronese, hauled before the Inquisition to account for his burlesque representation of the Last Supper, I do not defend it, but I thought it was right.

Veronica de Viggiani keeps asking me how it feels, standing here in my suit. How does it feel now? she says. So I consider how it feels.

What is the function of a suit? People wear them to work, or to funerals and weddings. They are themselves buried in them, married in them, sacked in them. They do traffic with the World in them.

None of these describe my own situation. I am only standing up in my living room, caught between worlds, ill-defined worlds at that: a public world that is only a memory; a private world that is open and shared.

On the day I quit my job I walked to a park in my suit and sat on a bench. What do you do in the ecstasy of collapse? The World had crumpled to a dimensionless point behind me: all that remained was the silent, peaceful, inevitable glide to oblivion which I had rapidly plotted. And I took off the jacket and folded it over my arm as I sat on the bench, and contemplated, among other things, the silkiness of the lining, its perpetual freshness.

You could date me now at that moment. This suit bears some signature of decay which places me there on that bench. The point of disinvestiture.

So, how do I feel?

The clothes you wear are not an expression of your personality—how could they be? Your clothes are scraps and fragments of an interpersonal field, a social membrane of textiles, real or merely possible, that stretches between us all. Thus our clothes may be differentiated by role, status, and other considerations, but they say nothing about our mood, our ‘personality’. Our feelings. They say a lot about our identity, however, and how we choose to position ourselves relative to others. In getting dressed, we occupy a quadrant of the total-clothes space of the World. That can be confusing.

I look at Veronica de Viggiani. How does she feel, I ask myself. She is wearing an assortment of expressionless but graceful, even elegant, clothes. Not diaphanous silks, nor breezy cottons—there is a certain pleasing gravity to her wardrobe. A considered but not over-thought colour palette. Is she dressed up, as I am? Not exactly. She could go to work in those clothes, I suppose. Difficult to tell with women.

We look at one another. And I think we are pretty absurd, pretty good. And so that’s what I say.

– A TURKISH JANISSARY

GENTILE BELLINI

– A WOMAN IN MIDDLE EASTERN COSTUME

GENTILE BELLINI

Footnotes ☞

1 “Must not the Imagination weave Garments, visible Bodies, wherein the else invisible creations and inspirations of our Reason are, like Spirits, revealed…” Thomas Carlyle Sartor Resartus p. 78 ⏎

2 “He [Leonardo] would make clay models of figures, draping them with soft rags dipped in plaster, and would then draw them patiently on thin sheets of cambric or linen, in black and white, with the point of the brush.” Vasari on Leonardo da Vinci ⏎

3 “By 1604, 62 percent of weavers and approximately 40 percent of all wool workers were women, not counting spinners who lived outside the city and who had always been female.” ‘Women and Industry in Florence’, Judith C. Brown and Jordan Goodman in The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 40, No. 1, (Mar., 1980), pp. 73-80 ⏎

4 “…While I – good Heaven! – have thatched myself over with the dead fleeces of sheep, the bark of vegetables, the entrails of worms, the hides of oxen or seals, the felt of furred beasts; and walk abroad a moving Rag-screen, overheaped with shreds and tatters raked from the Charnel-house of Nature, where they would have rotted, to rot on me more slowly!” Thomas Carlyle Sartor Resartus p. 60 ⏎

5 “…rough seams, tatters and manifold thrums…” ibid. p. 70 ⏎

6 “The Mercanzia’s chief purpose was to prevent reprisals and enhance the security of Florentines “throughout the world” by forcing Florentine merchants to honour their agreements and satisfy creditors.” John M. Najemy A History of Florence 1200-1575 Blackwell 2006 p. 110 ⏎

7 “Usò vestiti di pregio e calzari di velluto, che ancor si conservano dall’herede” – “He wore precious clothes and velvet shoes, which are still kept by his heir.” – Vasari on Veronese ⏎

Anatomy of Norbiton on HILOBROW

Original post at Anatomy of Norbiton: Sartorial

Anatomy of Norbiton

Short Life in a Strange World by Toby Ferris

Toby Ferris on Twitter

On the Paintings of Pieter Bruegel by Toby Ferris

All tapir illustrations by Anna Keen: portfolio