Norbiton (31)

By:

July 2, 2021

Anatomy of Norbiton: Pastoral

“…Each had a characteristic niche, a preferred biome. Swine fed on the mast of oaks and beech; sheep and goats, on the browse of maquis. Thus herders had to tend landscapes as they did flocks. The Mediterranean became a vast kaleidoscope of pastures.”

Stephen J. Pyne Vestal Fire

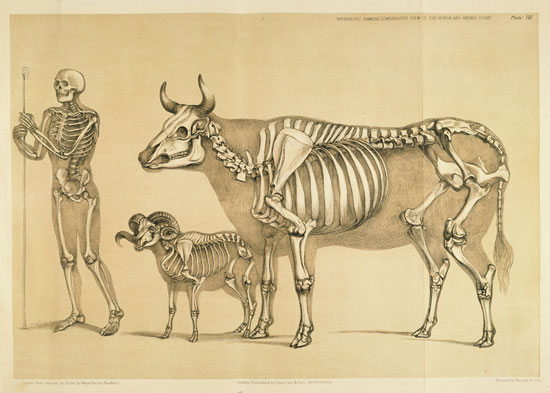

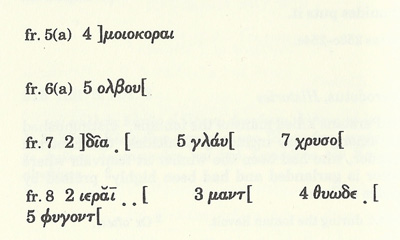

– A COMPARATIVE VIEW OF THE HUMAN AND ANIMAL FRAME (1860)

BENJAMIN WATERHOUSE HAWKINS

The pastures of Norbiton, with their sheep and their goats, their shepherds and oaten pipes, their wolves and wolfhounds, are long since subducted beneath the great cordillera of the city. In the city the rolling hills all run underground, walked only by transhumant ghosts and their grizzled flocks.

But fragments occasionally surface. When I was a boy my brother and I found a sheep’s skull, I don’t remember where. The sheep is a bony-faced animal, all precise geometrical projection of skull at the front, greasy cloud of rancid unknowing at the back, shivering bag of bones deep down inside. We took the skull home and placed it in our slender museum of skulls—a cow, some birds, a number of mice.

There sat the sheep, a docile object, one skull in a sequence of mammalian skulls. Hardly an emblem of freedom, however nimble the creature might once have been.

And yet even the no-longer-properly-existent will sometimes wink at you, out of the corner of your mind’s eye.

Ho there, shepherd boy!

Cities once feared the depredations of pastoralists. Shepherd and farmer were forever at loggerheads.

Herds, left to their own devices, will traject slowly across hillsides, across terrains, from pasture to fresh pasture. But once these herds have by whatever means been domesticated, then settlements, farmsteads, cities, will start to exert a weak gravitational pull on them. Pastoralists may be wild men, but even wild men need to trade. Cowboys will eventually ride into town in search of women and tobacco.

And when they are not trading, pastoralists lay waste. Hillsides and pastures are managed by fire, the forest kept at bay, grazing maintained; spiky, glaucous, pyrophytic plants or plants which grow rapidly in the aftermath of fire proliferate: white asphodel, spurge olive, sage, juniper, myrtle, holm oak, sage, buckthorn. But fire, used to manage, is also unmanageable; in the wrong mood, it will raze a city to the ground.

No cowboys now ride into Norbiton; no restless hoards threaten to torch and pillage up the Cambridge Road. The shepherds are long gone, and the fringes of the great cities are all suburb, not goat-grazed maquis.

– TRANSHUMANT SHEPHERDS IN THE FORO TRAINO, ROME, END OF NINETEENTH CENTURY

The restless hoards were only ever a rumour, a dream of danger; in reality it was just us, gangling shepherd boys, stuck out beyond the city with a stick and some sheep. Our straggling herds were entropic objects and are now stilled to nothing, to unreadable cuts on the shelves of Asda; but the pastoral instinct remains, somewhat skewed: an instinct for slow movement along historical channels, for a loose and easy mustering of resources (flocks of sheep, time), resources which distend over horizons, back toward which we might one day somehow escape.

The pastoral, to the city-dweller, is a simple idea, a picture of sanity, a vision of escape.

You go out (in your imagination) into the fields beyond the city, its pastoral hinterland, its contado, and you enter a more extensive, more expansive space. It is not wild—wildness encroaches, pushes up against you, is threatening, has a cloistering confinement and echo—nor is it cultivated. There is none of that forced growth, that intensively farmed productivity in Arcadia.

Rather it is an interstellar vacuum. There are rare and particulate sheep, still rarer particulate wolves; but for the most part it is just buoyant rolling empty space. And your mind, in this space, will not grapple, or contort, or penetrate integuments; it will distend, skim surfaces, evanesce.

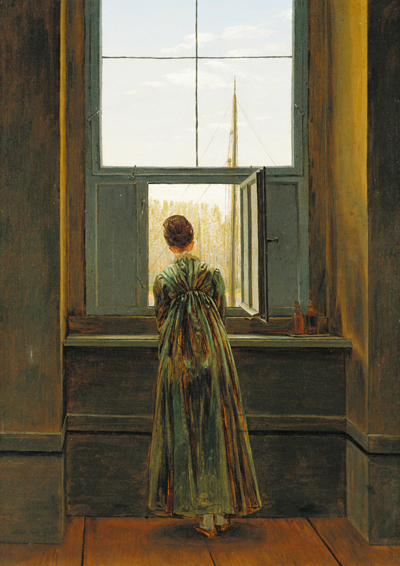

This is the pastoral to the hobbled nomad: a release of the mind, a simplification in the same way that the plane of a sail unfurled on the ocean is a simpler object than the hitched up port-bound roll of sailcloth with its dank runnels and grooves, its sodden geometry and sagging potential.

– FRAU AM FENSTER

CASPER DAVID FRIEDRICH

This simplification of Pastoral is available in several versions, as Empson foresaw.[1]

Many apartment blocks in Italy, as elsewhere, have communal drying spaces on the roof. You can take your washing up there, up among the TV aerials and heating vents and cooing pigeons, and drape it on the rusty wire washing lines that criss-cross the attic space. Life may proliferate in the multiple chambers of the building beneath your feet, in the hot and irritable city beyond the parapet, but up here there are just the sun and air, the geometry of the building, the sky intersected with wire washing lines; in short, the driest of dry gardens.

No one uses these communal spaces any more, Civ Clarke tells me. People confine themselves to their balconies, to lines strung beneath their windows. But Clarke, when he lived in Rome, used to escape regularly to the roof at the weekends with his sopping bundles. From these bundles he would individuate items of apparel and bed linen and hang them up and watch them dry; planes of colour, he says (forcing me to imagine Civ Clarke’s shirts, Civ Clarke’s underpants, Civ Clarke’s polyester sheets) snapping against fields of smoking concrete. No one would ever bother him. He might have been on the moon.

People have no imagination, he says.

No imagination.

When Clarke says that people have no imagination, he means they have no instinct for escape. They cannot conceptualise it. They tinker with the things that are, with the objects, real or fictitious, that cluster around them, press upon them, without ever in a gout of pure imagination sweeping them away.

Thus whole civilisations have built their necropolises in the form of a city, as though death and life were mere iterations of a single inescapable existence. The city of the dead corresponds to the city of the living at every point, and at every point there is a simple and uniform deviation. There is no possibility of escape: it cannot even be conceptualised. To slip this system is to be exiled, ostracised, banished; to experience (if that is the word) a sudden and irrevocable dismantling of existence.

But ours is a powerfully imaginative civilisation. We do not yearn for homecoming but flight, new lands, because we know that time is finite, space an invention, death not a thing at all but a violation of thinghood.

And so we build our cemeteries and crematoriums in the form of a pasture: stone, and grass encroaching on the stone, and memorial flowers, municipal rose beds, benches; fertile-seeming promontories and alluvial deltas pushed out into the seas of non-existence.

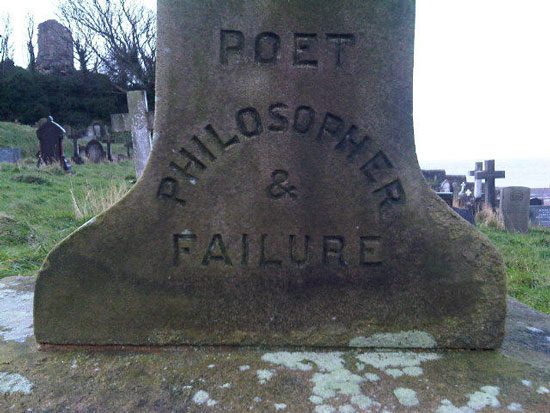

– NORBITON CEMETERY

Cemeteries may aspire to the condition of pastoral, but they are only elegiac in the broadest terms. We bury the dead in rows and chisel various data into their stone memorials, but for all the recording and docketing, very little actual information is forthcoming.

While you live you are a quantum of information in a network of similar but subtly differentiated quanta of information. When you die, the information dies with you. You precipitate out of the informational cloud of cities.

A cemetery, then, is a place of total information collapse, a vision of catastrophic simplicity where tiny disconnected slivers of junk data are encoded in headstones, the elementary dohs and lahs of a thousand lives swirling in an inaudible diapason nothing.

I am in Surbiton Cemetery with Mrs Isobel Easter, algorithmically alive and at large in the sun-warmed chilly autumn air, visiting the grave of Hunter Sidney.

This is the first time she has been out of her house and its garden in twenty years.

Surbiton Cemetery is continuous with Norbiton or Kingston Cemetery to the north, separated, or more properly conjoined, by the few hundred yards of the sewage works, all part of the great geological evolution of the dead that is South London.

We have brought a small picnic.

What do you eat at the rebirth of a woman? What did Orpheus feed Eurydice (in his imagination) to bring the pallor from her face?

I have brought apples. Coxes. A cox is a tight-knit apple, a youthful apple; when you bite into it you do not scoop the apple flesh from the apple like a gravel scoop scooping soft earth[2] ; rather you knap a great flinty flake from the side of the fruit, as thought the fruit had facets, informative inner structure.

So, I bring coxes, and figs, some berries and grapes, anything plucked or gathered, but also a wheel of stinking earth Camembert because this after all is the great stinking wheel of earth she is returning to.

Mrs Isobel Easter seems oblivious to the semiotic of her picnic, but is appreciatively hungry. We settle decorously in the grass between the headstones, and act out our fêtes galante, a mimicry of escape, of Resting on a Flight into Egypt.

In 1510, at around the time he died, Giorgione painted or was painting a Fête Champêtre, an odd concoction of clothed homoerotic males and orbiting naked females set in one of the first fully evolved landscapes in Italian Renaissance art.

– FÊTE CHAMPÊTRE

GIORGIONE

This is not a picture of men enjoying the company of naked women. It is a picture of men enjoying each other’s company in the presence of imaginary classicising nudes—art historical objects, which they have summoned to stand for the Antique in general. That shepherd in the background is not, contrary to appearances, getting an eyeful, but an education.

They have not exactly escaped out here, these young men. They are playing at Apollo and his complicit Daphne, the hair of the youth on the right assimilating to the bushes and trees which surround them, entangled in song and foliage and his own desire. Not escape, then, but pursuit and capture are playing on their minds. The fixing of objects, classical or sexual. That, after all, is the point of escape: it solicits the chase. Escape is a relation, not a pure state: you escape not only to, but from, and at any point in that system you are precisely located upon a trajectory.

And so these youths are triangulated within known fixed points—the antiquated stone trough, the naked muses, the lute, the velvet, the rustic buildings, the bumbling shepherd; between, in other words, the Antique, the Urbane, the Pastoral.

Escape, the pastoral, the life of the spirit are not a series of simple propositions; they are, on the contrary, an elaborate contrivance. Ernst Gombrich for example[3] , warty and knowing old toad, saw the genre of landscape not as the discovery of a natural sensibility but as the laborious invention of theoretical men, Leon Battista Alberti and Leonardo da Vinci and others. The pure, the seemingly simple is, he concluded, in fact a quintessence, a droplet of hard-won pure liquor glinting on the tip of an immense and intricate apparatus of thought.

He is right. Our imaginary pastoral escape is not a shutdown, a retreat, a retrograde movement at all but is, like a cemetery or crematorium, an output of the great smoking machine of the city.

The Fête Champêtre may not be by Giorgione at all. It may be by Titian. At around the time it was painted, Giorgione was dying, or about to die, slipping beyond the realm of configured information for good and all. Titian and Giorgione had both been apprenticed in Bellini’s workshop and had collaborated elsewhere. Perhaps Titian finished off the work of his friend, or worked up sketches or a prepared canvas to complete a commission; or perhaps Giorgione never knew anything of this painting.

This is not a calamity, all this loss and muddle. Rather it is a paradigm of understanding. We need something to reconstitute. It is, after all, how we understand anything—constructively, puzzlingly, speculatively. We marshal our intellectual objects—quarks and muons and Greek irregular verbs and attic script—across the variegated pastures of the intellect; bring back lost tattered text and elusive particles over our shoulders to the skittish flock.

The contemplation of remote detail, whether the provenance of a painting, the interrelation of an irregular verb, or the spin of a sub-atomic particle, is a pastoral of the intellect.

– ET IN ARCADIA EGO

NICOLAS POUSSIN

Mrs Isobel Easter talks about the apparently simple fact of being out.

She feels calm, she says, and in this place safe; suggesting by means of an ensuing silence that there may be wolves in the wilderness but they are elsewhere now, bothering someone else; and that there are in the world not only wolves and sheep, after all, but shepherds and gnarled old wolfhounds of various descriptions. A mobile defence might be better that a static one.

What she had before, her twenty-year sequestration, was not an escape at all but an escapement, a mechanism for parcelling out her momentous store of sprung energy in rhythmic, pendulaic routine.

Time had not stopped, but it had ceased to flow. To measure and regulate time is to regiment it; this second that second, they are the same. You might colour them differently, night or day, dawn or dusk, work or rest, happy or sad, bored or drunk, but they are the same.

This was, to repeat, no escape, there was nothing fugitive or impulsive about it: it was a hyper-dense present, all things assembled together. More of an exile perhaps, an exilic song lamenting and reconstructing a half-remembered elsewhere.

All this she says by silently chewing a fig and blinking at the moderate warmth of the late autumn sun.

Some epitaphs in the Surbiton cemetery are badly worn; others are crisply incised in their granite fields.

Hunter Sidney’s is still fresh. HERE LIES HUNTER SIDNEY, it says, or words to that effect (Hunter Sidney is not in fact his name). There are his dates. Husband, father, lover, poet, creator and curator of the anti-literature: the list could multiply, but we are not products of aggregation; so they (his family I suppose) have put nothing. Just name and dates. The fact of preservation and resistance is enough.

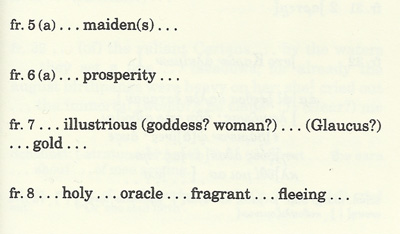

Simonides of Ceos, known to the classical world as among other things a writer of economical inscriptions, of epigrams, was for centuries little more than a name. All that was left of him were fragments of poetry, sometimes single lines or words, lifted from the pages of later grammarians; scores of epigrams in the Greek Anthology almost certainly mis-ascribed, a poem embedded in the Protagoras of Plato, much mangled in the recounting by Socrates. Other chance scraps.

The epigrams, ascribed to Simonides because of his reputation for epigrams, celebrate the glorious dead, the victors in various sporting contests. Very often they simply record a name, an origin, an accomplishment.

—Give your name, father’s name, native city, and victory

—Casmyulus, Euagoras, Rhodes, Pythian Boxing.

XXXI Planudean AnthologyHere the earth covers Pythonax and his brother, before they saw the full term of lovely youth. Their father Megaristus set the monument over the dead, an immortal gift to his mortal children.

LXXIII Palatine AnthologyI was garlanded twice at the Pythian Games, twice at Nemea, and at Olympia, victor not by my breadth of body but by my skill, aristedemus, son of Thrasys, of Elis, in the wrestling.

LII Haephaestion, On Poetry

They have outlasted their tombs. They bear no death date, nor birth year, (antiquity classifies its dead rather differently: Here lies Aristodemus the Wrestler), nor do they mark any actual remains. But the principle is familiar: simple, directionless, unordered, non-sequential markers in the pastures of Elysium.

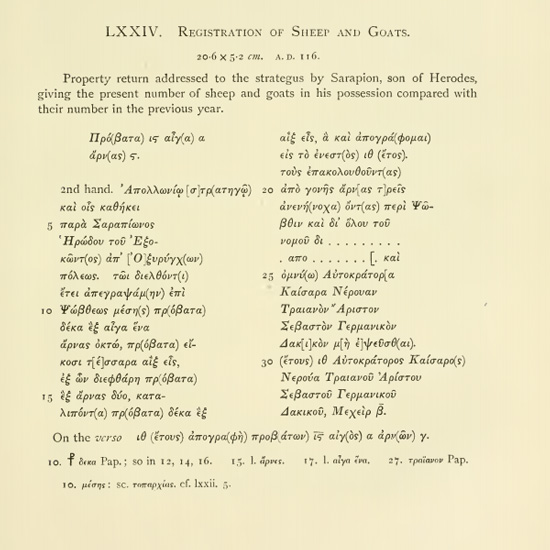

In 1896, two young Oxford archaeologists, Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt, turned their attention to a site at Oxyrhynchus in the Egyptian desert, where a felicitous combination of circumstances had preserved the contents of the town dump in dry sand for a thousand years. The dump was mostly papyrus, the mycelial map of a civilisation.

Grenfell and Hunt were tweezering and sorting and translating for the rest of their careers, shepherding these lost bleating scraps within the secure pens of Academia.

Their work yielded a thin but steady stream of bits of Simonides. We have him now in book form, words and lines reconstructed, annotated, laid out in differentiating typescripts, square brackets, angle brackets, braces, speculative completions: a weft of typographical complexity fixing in place this lyric babble, the skitter of bright words, the sort of disjunct and gnomic utterance you might expect from beyond the grave.

I doubt whether sheep ever grazed among the ruins of Oxyrhynchus. Egypt has its fertile plains, its animal husbandry, but Oxyrhynchus is down river and built above the floodplain in a barren desert country.

But I remember Hunter Sidney telling me that in his first novel (unpublished) he had written something about sheep—or perhaps it was goats—grazing in the shadow of vast and empty motorway flyovers in Sicily, proto-ruinous objects. It was, he told me, a classical image. The classical world, both to those Renaissance dandies in the Giorgione-Titian, and to us, is a spectral, incomplete one. A world of ruined cities and their inert, despoiled remains, mute tombs, amongst which sheep graze.

Isobel Easter and I contemplate for a few minutes Hunter Sidney and his spare epitaph. Here lies one, she says, whose name was writ in the Internet.

And then she says to me something I do not expect. It is not about Hunter Sidney, not about her sequestration, not about her husband and his odd history, or about Clarke or the Ideal City or the anti-literature; nor pleasantries about the weather, or the picnic. But about me. She says something about me.

She says, be sure to get out.

Just that. And in that moment I know that she sees me. As though a telescope set up on a city roof had picked out a shepherd on a distant hillside, playing his pipe of green corn alone. She sees me. No one sees me, not since Hunter Sidney died and Veronica de Viggiani left for Rome. No one sees me.

What does she mean, be sure to get out? She means that this whole visit, her emergence from twenty years in a room alone, the fresh gravestone, the picnic—the picnic I brought—is all about me. She is shepherding me, not I her. By getting out she means, return to the world. The summer in the hills is over. It is time to leave the Fête Champêtre, the classicising nudes, the long-legged leaping from rock up to rock, and return to the city.

All this she says in that one phrase. Don’t be like me. Don’t be like him. She sees me, knows me; has seen me and known me all along. And suddenly there is no point being out here in these mental hills any more.

Mrs Isobel Easter walks home. I walk with her as far as my own front door, and let her finish the walk alone.

We have an idea of escape. Escape, according to this idea, is omnidirectional. There are no constraints. The hillsides roll on forever and you will follow the grazing flocks with your oaten pipe, wherever, and forever.

But this is not so. Escape is always from and to. It has its axis. And it has its vectors of return. What we return to might not look like what we left—it might be a different city, in a different country—but the configuration will be familiar.

And so somehow you learn that you might be able to interleave escape, the violent boyish gadding over hills, into the daily texture of your life. You do not require sheep’s skulls like props to a yokel Hamlet; you merely need that shepherd’s knowing sensibility, the loose control, the letting things go a little, the letting them stray.

Things will shift around you. You need only pay attention. A gust of wind, for example, as you eat your lunchtime sandwich, bearing some atavistic memory of a time when you might have been a feared interloper in the city with the threat of wildness about you.

– MEETING OF ANTHONY AND CLEOPATRA

GIOVANNI BATTISTA TIEPOLO

The same gust of wind that speaks to the sailor as he idles in port. Ports have their nomads drifting in, the sound of gulls and the smell of the sea; the nomads talk of other experiences, other ways of living, other cities they have seen—they talk of the women of Berrylands, the dark wines of Worcester Park; of Petersham and Richmond and the streets paved with rare earths, Itrium and Ytterbium; they recall the mystical savagery of New Malden, and the Cyclopes of Norbiton.

Perhaps after all it is the furled sail in port that speaks most of escape; in a port you are always outward bound. In the same way, the nomad is only a nomad when he comes into town to trade, when the city sings him into existence; it is the city sings the life nomadic.

Footnotes ☞

1 “The pastoral process” consists of “putting the complex into the simple.” Some Versions of Pastoral p.23 ⏎

2 “how he look

down by now in soft boards, Henry, pass

and what he feel or no, who know?”

John Berryman, in The Dream Songs, meditating on the softness of coffin wood ⏎

3 in “The Renaissance Theory of Art and the Rise of Landscape”, Norm and Form (1966) ⏎

Anatomy of Norbiton on HILOBROW

Original post at Anatomy of Norbiton: Pastoral

Anatomy of Norbiton

Short Life in a Strange World by Toby Ferris

Toby Ferris on Twitter

On the Paintings of Pieter Bruegel by Toby Ferris

All tapir illustrations by Anna Keen: portfolio