Norbiton (27)

By:

June 4, 2021

Anatomy of Norbiton: Microscopical

“Knowledge so conceived is not a series of self-consistent theories that converges towards an ideal view; it is not a gradual approach to the truth. It is rather an ever increasing ocean of mutually incompatible alternatives, each single theory, each fairy tale, each myth that is part of the collection forcing the others into greater articulation and all of them contributing, via this process of competition, to the development of our consciousness.”

Paul Feyerabend Against Method (1975) p. 14

– VIEW OF DELFT,

JOHANNES VERMEER

Pictures are like prepared slides—slides prepared for microscopical inspection. To look at a picture hanging in a gallery is akin to looking down a microscope at some object or other and marvelling at its ultrastructure.

Take this picture of the town of Delft, for instance.

The painter has laid out his subject in a translucent medium, it seems to be held in suspension in a clear fluid, an object of curious wobbling or refracted surfaces and planes, pungent angles.

– VIEW OF DELFT, DETAIL,

JOHANNES VERMEER

And however far you see into it, beyond that first epidermal darkness, that permeable barrier of walls and docks, down into the interior mid-region of sunlit rooftops; however far you see into it, you know there is further to go. But your lens—the painter, the painting, your eyes—can carry you no further. You are at the utmost of resolution. You strain at the boundaries of perception, marvelling, wondering, but ultimately frustrated. However much you are shown, there is more to see, some fundamental deep-lying arrangement that holds the key to all this. You feel.

How has the painter—Vermeer, of Delft—managed to make of this town (a small town, admittedly) such a very small and compacted object?

Vermeer was born in 1632, the same year as Antoini van Leeuwenhoek, great pioneer of the microscope, also of Delft. It pleases me to imagine that Vermeer, interested in optics and optical devices, knowing everyone in Delft as everyone knows him, pulled Leeuwenhoek’s microscopical lens over Delft, in his mind’s eye obviously, and rendered it as an animalcule.[1]

And the city does indeed have an ultrastructure, which we experience on a daily basis. We move through it like an endoscopical eye, peer into its crevices and contours, insinuate ourselves into its invisible chambers.

And in the same way that Vermeer found himself on this particular day (or sequence of days), washed up on an opposite bank, trying to sketch some aspect of the town that puzzled him, so too have I floated momentarily free of the city of Norbiton.

I am standing in a pond, thinking about the small, the very small; and hunting diatoms.[2]

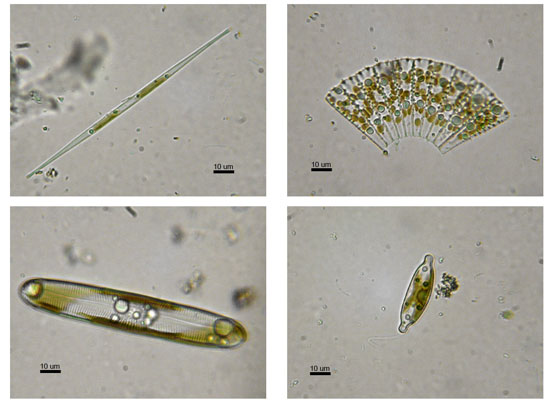

– DIATOMS, WARIOUS,

PHOTO: DAMIÁN H. ZANETTE [PUBLIC DOMAIN], VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Diatoms are invisible plants, typically collected in jamjars.

I am hunting them in the conviction that, while I have a microscope and a pond and jamjars, I will fail to see any. My primary amazement will be in getting a yield of diatoms on to the slide at the bottom of my microscope, and unequivocally identifying them; not in the diatoms themselves.

My secondary amazement will be in the diatoms themselves.

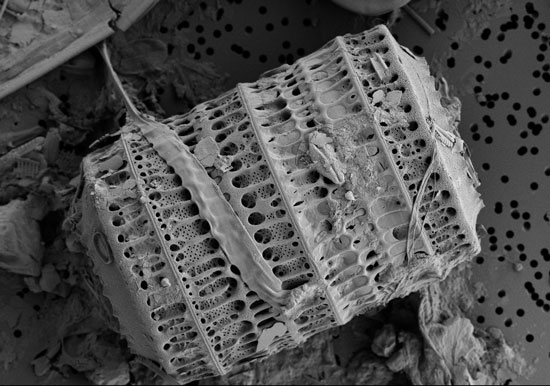

– PARALIA SULCATA,

PHOTO: JMPOST [GFDL (HTTP://WWW.GNU.ORG/COPYLEFT/FDL.HTML) OR CC BY-SA 3.0 (HTTPS://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY-SA/3.0)], VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Antoini van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), great pioneer of microscopical investigation, habitually made no hypothesis about what he was seeing.

He merely observed, noted down what he saw, and dispatched those notes to the Royal Society in London where they were translated,[3] discussed, scoffed at, theorised over.

It was as though, situated at the actual interface of the World and the Very Small, he recognised intuitively that he had no framework of knowledge in which to set all of this. What he was looking at was not simply a question of the same things only smaller. The microcosm was not a version of the macrocosm; there was no self-similarity, no sliding scale of being.

There was only a baffling disjunction. The very small does not know that we exist, that we watch it or care about it. It has not only a life of its own but a wholly different sphere of possession which, for all our microscopical probing, intersects with ours almost not at all.

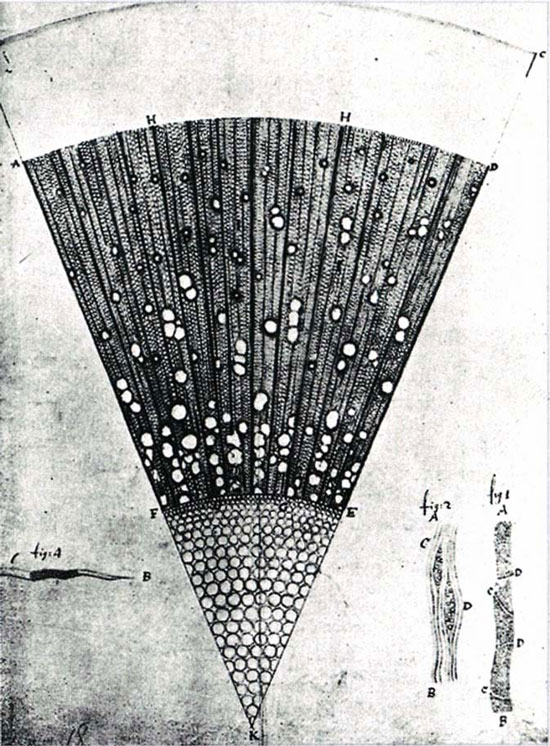

– A MICROSCOPIC SECTION OF A ONE-YEAR-OLD ASH TREE,

LEEUWENHOEK

What is the meaning of small?

Small is a relational adjective, well-adapted for use in the world of medium sized things in which we came to be.

Beyond common experience it ceases to be relevant. Over some event horizon determined by the resolving power of the lens of our eyes, and, in the end, by the wavelength of light, small shades into invisible.

In the fifteenth century intelligent men were convinced that the middle air, separating this terrestrial plane from the celestial sphere, was populated with an infinite invisible proliferation of spirits, angels, incorporeal beings, every bit as varied as the visible natural world (for more on which, see Celestial).

This strikes us now as fanciful. But in truth they were only looking in the wrong direction. Look down down down, into and beyond the smallest thing, and there are smaller things, and things still smaller, themselves striding giants to the smaller and yet smaller things beyond; and so on, down and down and down the ladder of creation.

We are not looking down to a foundation, just as Aquinas was not looking up to a ceiling when he imagined the chain of being tumbling earthward; rather we are peering in imagination at a matrix of interference, a Borromean curiosity of knotted pattern and energy, a welter of ornament ornamenting no structure; a self-sustaining cosmetics of nature.

A microscope gives form to the invisible, clothes it with light. But it also sets it floating in an inimical space—our own. The object’s customary relations are no longer relevant, it is held and simultaneously lost in a flood of perpetual translucence. These are not objects with a narrative and structured life; they are just happenstance whorls of matter, a texture of existence.

I am moved to enquire if there is in fact any such thing as a big thing? Let us postulate that there are no big things, just aggregates and communities and colonies and heaps of cells, or molecules, or particles; fields lumpy with instances; there are no years, only days, no days, only minutes; no seconds, only nano-seconds, each of which passes you by, invisible. The world, your world, is not derived through some chain of ratiocination from underlying big simplicities, but is built up higgledy-piggledy from an accidental proliferation of the very very small.

In the same way, you do not have a personality, a lump of primal matter somewhere etched with the blueprint of who you are; you have only a statistical sample of your actions, with its outliers and its medians; you do not have a beginning a middle and an end – a story; you have an unlocalisable muddle of fizzing energy called a ‘here and now’.

Dell’Aquila has put a pond in his garden. Not a pond. A pool. It was my idea. An expanse of water not quite the width of the parterres, reflecting the Temple—the folly—as you stand on the terrace, making the distance difficult to read, vague, shimmering. An aqueous middle ground.

There is talk of a small fountain to provide a trickle of movement, and of orange fish, of lilies and aquatic grasses; but for now there is nothing, just this sheet of water three feet deep.

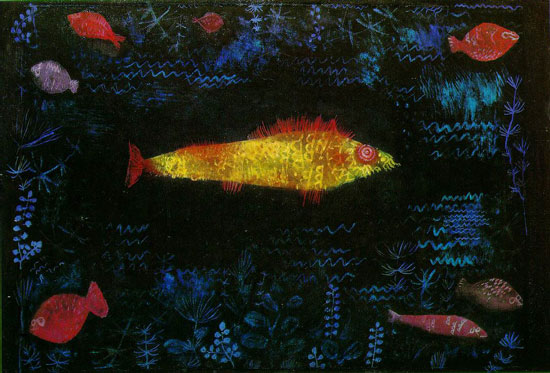

– THE GOLDFISH,

PAUL KLEE

Thus it is that I find myself standing in a pond in a pair of waders, in the first days of autumn, skimming the surface for algae, dropping bulbs, and scooping up diatoms in jam jars.

Dell’Aquila is also here now, working on his folly, laying a course of bricks, tip-tapping them and nudging them home, inspecting their lines, rotating half-bricks in his hand and hitting them, breaking them in half, dusting at the broken edges.

The best moments are isolated oddities, I sometimes think, not the culmination of some grand narrative. You suddenly find yourself occupying a bit of space-time, and it is OK. There is no useful before, or after.

I am here, here is Tony’s garden, but Tony’s garden is a parcel of space that could be anywhere; it is detached; free-floating; we are, the pair of us, an object under a microscope, in a pool of light, with our fine structures, our impervious distance.

Small, to repeat, is a relational adjective.

In a gallery or a church you stand closest to the large paintings. It is inescapable.

In absolute terms you stand closer to a small painting, but in relation to the size of the painting you do not stand as close as you do to a frescoed wall, for instance. To stand that close to a small painting you would have to press your nose to the panel.

And if you did press your nose to the panel, you would experience a perceptual change. You would swim in the colour fields, mesmerize at the brush strokes. I once spent an hour in the camera degli sposi at Mantua with my nose an inch from the plaster, taking unreadable snapshots of the microstructure of the plaster.

– SOMETHING OR OTHER,

MANTEGNA

You destroy space by close looking, you dwell among the ornament, the ultrastructure of paint and surface.

The Netherlandish painters of the fifteenth century developed an art of wonders that ran alongside the experiments in scientific space ongoing in Italy. Linear perspective as developed in the Renaissance is a way of tidying objects in space. Everything has its place on the shelf.

But Robert Campin and van Eyck and van der Weyden had no need for Linear Perspective—their spatial systems were done by eye, rule of thumb—because they had oils, and oils allowed them to build objects with layers of refinement unimaginable in Italian art of the same epoch. Theirs was an art of accumulation.

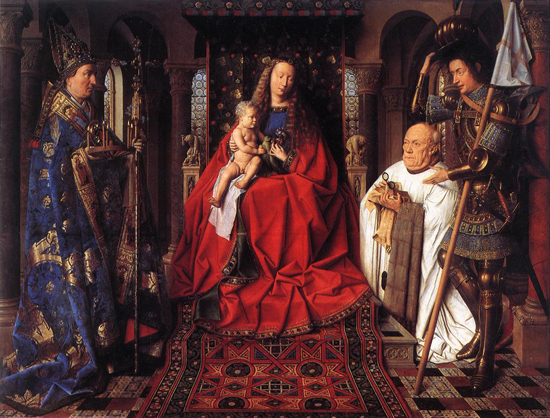

The panels of van Eyck are untidy with ornament and objects in the way that a workshop is industriously untidy. And all his extant panels, from the very large (Ghent Altarpiece) to the large (Canon Joris van der Paele in Bruges) to the middling (Chancellor Rolin in Paris; Washington Annunciation) to the small (Madonna in the Church in Berlin) testify to the artist’s microscopical eye.

– MADONNA WITH CANON JORIS VAN DER PAELE, DETAIL,

JAN VAN EYCK

There is in his work a universally unfolding clarity at all resolutions, on every scrap of every panel, as though he were painting the ultrastructure of things. This is an art concerned with the representation of materials and pattern, rather than drama or personage.

In an altarpiece completed by van Eyck in 1436, Canon Joris van der Paele is depicted kneeling before the Virgin, in the company of Saints George and Donation.

JAN VAN EYCK

The old man is clutching a book of hours, and has taken his spectacles from in front of his watery orbs, the better to contemplate the blinding clarity of his vision. No longer does he look through a glass darkly, or wander the shaded labyrinth of theology and faith laid out in scripture and commentary. He merely takes it all in with his own eyes. He finally, properly and unambiguously sees; reads in a single visual gulp the layered typological patterns. He understands with his eyes.

– MADONNA WITH CANON JORIS VAN DER PAELE, DETAIL,

JAN VAN EYCK

Or perhaps—look again—he is not using his eyes at all. We have caught him in a moment of imaginative suspension. He sees nothing. He is not focussing on the figures that surround him, or indeed on anything. He has removed his glasses because sense is fallible, needs correcting with reason and revelation; and because he is subject to a vision. What we see is a representation of that raddled vision (the Madonna as altar, the child as Eucharist, parakeet as Paraclete, and so on). He contemplates objects of the imagination.

The Canon has a vision, and we see that vision represented, because to see with the eyes was once a touchstone of truth.

Hannah Arendt in The Human Condition hinges much of her argument on the moment when Galileo turned his telescope on Jupiter and saw that it had moons. The world was no longer susceptible to the combined powers of unaided observation and reason, it was necessary to accelerate understanding by the use of tools.

She calls this the Archimedean moment, the moment in which mankind learned to stand sufficiently outside itself that it might hope, in truth, to comprehend the world.

To properly see, we need not to correct but to multiply our modes of looking—up to and including looking, so to speak, with mathematics. We need to increase our sample size.

The clarity available to Canon Joris, even in imagination, is now lost to us. Happily perhaps, because it was an illusion.

Clarke once said to me, when we were up in the isolarium looking down over distant and impenetrable Norbiton like Vermeer at Delft, words to this effect: what are other people if not magnifying lenses which you can swap in and out between you and your object of study in various optimal and non-optimal configurations? You want to look at music? You swap in this person. You want to look at architecture? That person. And what is a city full of people but a great magnifying machinery, an array of mirrors and lenses?

It was a typically paranoid vision (he was accusing me of swapping him, and others, in and out); one which engulfed the city in a somewhat conventional thought. It is one thing to talk about a state or a bureaucracy in terms of universal microscopy, willed or actual; quite another to implicate the unruly city.

But NORBITON: IDEAL CITY, like van Eyck’s Canon Joris, was perhaps just such a corrective and magnifying array, which took as its model not a spatial event (an actual city) but an ideal one (a literary city). If there is a disjunction in scale, perhaps it lies here: not between the city and its individual citizens, but between the city as fact and the city as imaginary spyglass.

The city—the empirically real city—is large and we are small. You can walk from one end of it to the other, and it will take time. And as you go, you stub your toes on its stones, refuting all manner of ideal confabulations, thus.

A city is not a microscope, nor are its citizens microbes. A city is just buildings and people, for better or worse.

But an imagined city—The New Jerusalem, Babylon, Norbiton, Delft—is a lens which you can mentally supply at will.

– TOWER OF BABEL,

PIETER BRUEGEL THE ELDER

The possibility remains that I am experiencing a sense of charmed detachment standing here in the pond only because I am aware of having discharged a duty. My sense of well-being has a history after all.

The duty in question was to restore the photograph Hunter Sidney stole from dell’Aquila’s house to its position on a table in a room at the back of the house. Hunter Sidney charged me with this duty before he died. He wanted the photograph put back, and the world, in some small way, reconstituted.

He was very explicit. The photograph in its frame had to be replaced exactly. He did not want to die with this fragment out of place.

Small things, he believed, can have their location; each detail can be set in its place if need be.

He may be right, even though he is dead, and I may be wrong, even though I am alive. But one thing is sure; the attempt to place objects in a given relation after you have died is a mark, if not of insanity, then of irrationality. Things can have no location whatever, once you are dead. They can stand in no relation to you. Wholesale detachment is the mark of the dead man.

But I put the photograph back all the same. And I take some consolation in the idea that, while this is an act that places an object in coordinate space, and by extension me in narrative space, it is nevertheless an invisible act, an act of invisible smallness, and therefore pleasing to my own gods.

What you see down a microscope is not a true revelation. You do not suddenly grasp, whole, what it is you are looking at. Robert Hooke relates how, in preparing his Micrographia (1665), he made repeated observations in different lights in order to produce a composite drawing on paper, “because of these kinds of Objects there is much more difficulty to discover the true shape, than of those visible to the naked eye.”[4]

For Leeuwenhoek it was even more tortuous: he could not himself draw, but relied instead on the collaboration of local draughtsmen, with whom he no doubt bumped irascible heads over his tiny machines.

The fact of a microscope, in other words, does nothing to resolve problems of clear seeing, let alone epistemological doubt. It merely shunts you along to a different horizon; you always stand short of something.

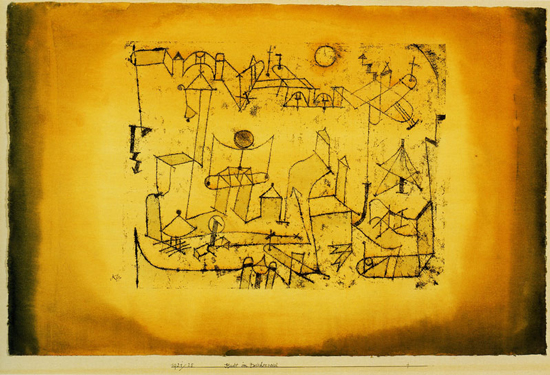

Five hundred years after van Eyck painted his Canon Joris, deep in the microbial smallness of what for the fifteenth century was the invisible future, Paul Klee, a painter grown up in a world of newly awakened quantum uncertainty, preoccupied himself with microscopical visions, visions of the very small, speaking of his work as ‘andacht zum kleinen’, devotion to small things.

This is cellular life he paints, pond life. There is no gulp of the eye at this scale, just a perpetual and rotational grazing over tiny objects of knowledge, cells, protozoa, diatoms.

– UM DEN FISCH,

PAUL KLEE

I have a suspicion that Klee did a lot of standing about in ponds. Rock pools. Gardens. His is anyway an art of genial detachment.

In his Pedagogical Sketchbook, written to support his lectures at the Bauhaus, Klee speculates that the repetition of like units is structural.

– LANDSCHAFT MIT GELBEN VÖGEL,

PAUL KLEE

Thus had there never been more that a single diatom in the cosmos it would have been interesting; but it is only in their meaningless proliferation both of number and form that they become a structural element in our world. Similarly with paintings. Similarly with you and me.

There is no disjunction in scale, in Klee, between objects of wildly differing size. A microbe might be a fish or a city, all float in the same frame, in the same way; they can be read, not as articulate wholes (from which we, observers, might be excluded) but as sequences of—in the case of a city—rooms, pavements, rooftops, facades and faces, in no particular order, self-sorting, arranging, not a space at all, but a known open sequence, from which exclusion is not even a possibility.

– CITY BETWEEN REALMS,

PAUL KLEE

Footnotes ☞

1 The View of Delft was finished a decade or more before Leeuwenhoek started to make his observations. ⏎

2 “The surface mud of a pond, ditch, or lagoon will almost always yield some diatoms. They can be made to emerge by filling a jar with water and mud, wrapping it in black paper and letting direct sunlight fall on the surface of the water. Within a day, the diatoms will come to the top in a scum and can be isolated.” Chamberlain, C. J. Methods in Plant Histology, (1901) University of Chicago Press ⏎

3 To begin with by Henry Oldenburg, and then by Robert Hooke, who taught himself Dutch for the purpose. ⏎

4 Micrographia fol. f2v. ⏎

Anatomy of Norbiton on HILOBROW

Original post at Anatomy of Norbiton: Microscopical

Anatomy of Norbiton

Short Life in a Strange World by Toby Ferris

Toby Ferris on Twitter

On the Paintings of Pieter Bruegel by Toby Ferris

All tapir illustrations by Anna Keen: portfolio