Norbiton (21)

By:

April 23, 2021

Anatomy of Norbiton: Horticultural

“Any regular lattice or symmetrical design is always capable of further development by the creation of links between its constituent elements. In this process a rich network of progressive intricacy can be seen to emerge, for it is in the nature of any geometrical periodicity that it can serve to generate fresh periodicities in a hierarchy of forms.”

E.H. Gombrich The Sense of Order p.80

– ANNUNCIATION,

FILIPPO LIPPI

A garden in the IDEAL CITY is not merely the proper dwelling place of herbaceous plants. It is, to adapt a phrase of Francis Bacon’s, a way of vexing nature.

Bacon was talking about art and craft, and by extension experiment and observation. By squeezing and prodding the natural world it was possible, he believed, to wring from it illustrative instances of its processes and oblique evidence of the constants and structures underlying those processes, which, taken together and properly considered, were tantamount to UNDERSTANDING, or even TRUTH.

Considered in this light, a garden is not a play on space or an allegory of paradise but a datastream of plantlife, and in particular of cultivars and their performance in a given location. It is a continuous catalogue, in short, of an experiment. The aesthetic ends of the garden are merely a placeholder, a dummy object never attained. The beds and borders, so far from bounding, shaping, delimiting, decorating, are themselves the substance in question. The plants are not in the garden: they are the garden. GARDEN is no longer an object of knowledge, but a form of inquiry.

I have some trouble reading gardens in this way, because while I am attached to space, air, and light—and to allegories of paradise—I am only moderately fond of plants in general, and of flowers not at all.[1]

I understand that flowers are necessary, and I note with approval their qualities of contrastive colour and fragrance (although with regard to the latter I should state that my sense of smell is largely atrophied by a habit developed in childhood, I believe, of breathing through my mouth in the presence of offensive odours). However, insofar as they have acquired a certain perceptual kudos in garden culture, an enthroned quality, such that gardens are now frequently about flowers; so they have also become lost in their own futile blaze of glory. I would contend that flowers in and especially out of a garden are, in aesthetic terms, a hypertrophied mass.

– VASE OF FLOWERS,

JAN BREUGHEL THE ELDER

This is, in the first place, because a flower is a circular aesthetic object. A flower is considered beautiful because it resembles itself.

In the second place, I hold the marginal detail of a visual experience to be more interesting than the putative focus of attention.

Confronted by, for instance, an altarpiece—a quattrocento sacra conversazione, a Netherlandish Annunciation—I can endlessly examine the tassels and embroidery on the rug or the tiles on the floor.

– MADONNA AND CHILD WITH CANON JORIS VAN DER PAELE,

JAN VAN EYCK

But it is with a shock only slightly dulled by habituation that I realise that at its centre there is, say, a Madonna and Child—bashful, demure, privileged, anointed—and this in spite of the fact that the Baptist is frequently pointing at her.

– MADONNA AND CHILD WITH SAINTS JOHN THE BAPTIST AND DONATUS,

ANDREA DEL VERROCCHIO

In truth the Madonna is almost certainly the first thing I see. But it is simply a presence that serves to indicate the genre: the faces are interchangeable, like so many acanthus leaves. So too with flowers, and to a lesser extent plants. I see flowers, I know that I am dealing with a garden—that, in parenthesis, the garden exists for them—and I immediately stop looking at the flowers.

I have little patience with devotionalia.

All this I note internally while standing in Emmet Lloyd’s (father’s) Ur-nursery, grimacing at his great expanse of plants.

The Ur-Nursery supplies the various retail nurseries dotted around Empirically Real London in the Lloyd name. It is an extensive and irregular grid of miniature fields abutting one another, each host to a particular shrub, the changes between one shrub and the next rung like structural chimes in some minimalist cosmic music. It is in effect a colossal anatomy of a herbaceous border.

– HOFGARTEN, BAYREUTH

In addition to the fields of shrubs there are also greenhouses, cloches, irrigation systems. And both indoors and out there is a particularly large volume of flowers in bud, grown to be cut, to supply I suppose local supermarkets, or florists, or funeral homes. The nurserymen make their various rounds on tiny tractors.

Confronted thus with a saturation of flowering plants, chosen for their bigness, their brightness, some forced to flower before their time (according to the arts of The Gardener), all doomed in any case to submit to the commercial pressures attendant on a quick-withering product, I note gloomily why it is that flowers, as decorative objects, are compromised. They are terminal objects. They lead nowhere, are only arrived at, can only function as repetitive, rather than evolving, devices. While in a meadow or a forest they act as ports at which bees or other insects may dock, a way of interfacing the plant with the space; in a decorative border they are a sterile abundance, a volatile excitement, a dead end.

Hunter Sidney concurs. He says that he never sees a bunch of flowers without thinking of decapitated heads and lopped limbs, a piled triumph. Flowers, he says, belong on plants, or in the compost.

My inability to individuate, almost to see, the Madonna in a Renaissance painting and my distaste for plants may indicate nothing more interesting than a peculiar underlying pathology.

But I believe there to be a conceptual foundation to both. The fact of the matter is, I do approve of certain plants—and in some cases the handling of certain flowers—as properly decorative motifs. A trailing vine or acanthus leaf, displaced to the margins of a visual experience, is, I find, a pleasingly mobile object of contemplation.

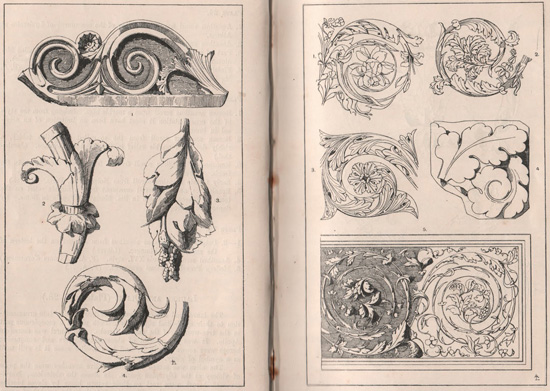

– FRIEZE WITH ACANTHUS SCROLLS AND A MAN (HERCULES?) FIGHTING A LION,

JEAN LE PAUTRE(?)

Needless to say, my great work on ornament (working title: The Roots of Ornament: Cosmos and Cosmetics—unpublished) had several very important chapters detailing the history of vegetative decorative motifs and their proliferation from Egypt through the Near East to Greece, and from Greece to the world, the analogies and genealogy of the lotus, the palmette, the acanthus, the arabesque—a history first outlined by Alois Reigl and W.H. Goodyear in the 1890s.

– STUDY OF ACANTHUS FORMS,

JEAN LE PAUTRE

My own voluminous—you might say, decorative—addition played on the insinuation of the tendril, so to speak, into the representational plain. Figures in paintings, according to the logic of this somewhat obsessive imaginative conceit, are the ultimate manifestations of an ornamental line. The ornamental line takes momentary form in figures or objects; the actors in the Renaissance istorie are no more than highly elaborated instances of the decorative imagination: so many green men, mythical beasts, grown from a marginal doodling pen let loose on the broad plain of a tavola quadrata, a chapel wall, a canvas.

The theoretical constraints in operation in the Roots of Ornament (unpublished) were elusive, numinous, and largely ineffectual. As it happened, the book stopped short of suggesting that figures were themselves ornament. Instead I exhaustively (and exhaustingly) troved through elements of ornamentation within the picture plane: the Hebrew hems of Marian dresses, the fruits strewn and detached, the geometries of tiles and coffered ceilings (linear perspective a trellis around which, I fancied, matter draped itself like vines); marbling of books, patterned glint of jewels, calligraphy and inscription, the caparisons of horses, the wings of angels.

The figures themselves I discussed in terms of ornato against puro[2] —the less ornamented stolidity of Masaccio as against the classicised billowing robes of Lippi or Botticelli, the self-declaratory scorcio of a twisted quattrocento head against the more insidious and illusory smoothness of the cinquecento ideals. This in turn allowed me to discuss them in terms of rendering of material, cloaks, hems, embroidery, returning them in a behindhand sort of way to the realm of ornament.

Ornament, it seemed to me, was everything, because of its qualities of repetition, self-similarity, patterning, which could be restful, agitated, irregular, varied, intellectually or emotionally stimulating, as the case may be. It was intuitively obvious to me, turning my head from the painting to the gallery or church in which it hung, that the painting was merely a more intense, perhaps more subtle patterning of the ornament which ran anyway through architecture, through decoration, through materials—in short, through the World in its entirety, one way or another.

– STUDY FOR A FRIEZE WITH ACANTHUS AND SIREN,

TULLIO LOMBARDO (?)

No wonder I liked art. And no wonder that I lost sight of the Madonna, peering like a shy monkey from the leafy scrollwork. The repetitiveness of ornament lulls the senses.

We have strayed a long way from plants, their propagation and cultivation. To repeat, I am mildly averse to them, and no doubt the aversion is bound up with my memory of that intractable madness, years spent tracing the endless loops and whorls and arabesques of my idée fixe. My scholarship was a psychologically aberrant object, a rootless self-sustaining system of idiocy. Burning the manuscript and typescript and paraphernalia—which I did, on my allotment, in a fit of autumnal glee—was one useful step in moving away from it; but I could still feel its presence.

Seeing all these plants now in their ordered profusion was provoking in me a familiar anxiety, a familiar need to draw all this into some bigger, more encapsulating pattern. I had come here simply to source plants for the gardens in which I was working, but had stumbled upon a greater need, for a proper mental construct in which to hold plants. A full, predictive taxonomy in which no new plant could not be swiftly assigned its place.[3] A basis, in other words, not merely for understanding (where to plant a dahlia, in which soil, how to propagate it), but for seeing, and ultimately for thinking.

I would, in short, seek to garden henceforth in a garden of known objects, however limited an objective that might appear.

Perhaps here is a possible alternative explanation of my peripheral vision: I lacked, or lack, an adequate taxonomy of Virgins. Each one I confront is, like a cathedral, a case unto itself.

Michael Baxandall has described[4] how each Virgin in a quattrocento (and indeed trecento) Annunciation conformed to one of four types, depending on the precise moment in the annunciation story (as told by Saint Luke) in which the painter had caught her.

Thus the Virgin was either experiencing (and expressing) conturbatio (‘… and she was troubled’), cogitatio (‘… she cast in her mind what manner of salutation that should be’), interrogatio (‘… how shall this be, seeing I know not a man?’), or humiliatio (‘… behold the handmaid of the lord’).

– ANNUNICATION,

SANDRO BOTTICELLI

– ANNUNICATION,

FILIPPO LIPPI

– ANNUNICATION,

ALESSO BALDOVINETTI

– ANNUNICATION,

CARLO CRIVELLI

And so, Baxandall notes, the trecento was adept at differentiating cogitatio from interrogatio, a subtlety largely lost in the quattrocento; the late quattrocento saw a vogue for conturbatio, and so on.

This is, clearly, a useful beginning to a full taxonomy of Virgins, albeit limited to gesture. Additional work, I can see, would take the historian of virgins in the direction of Byzantine prototypes and their minute differentiations (the Virgin Hodegetria, the Virgin Psychosostria, etc.), thence to paraphernalia and attributes: pomegranates, goldfinches, genitalia; Christ children standing, sitting, pointing, blessing; lilies in vases or clutched by angels; doves, Gods the Father, lecterns, rugs, rude screens in various Classical orders, swags, loose fruits, more birds (peacocks, partridges, swallows), fauna (snails, dogs), location (spatial coordinates); and might even, in a sacra conversazione, extend to computing the character of the Virgin from the particular retinue of Saints.

But saying all that, I can see that such a project could be realised without once looking at the face of the woman in question. There, once again, I break down.

The carpets of flowers common to Annunciations and to the Primavera of Botticelli are a form of naturalised or bolted ornament. And as with their ornamental forebears (for instance, the acanthus), they are elusive of identification.

In the Primavera, for instance, over forty separate species have been individuated, but not securely named. Are those forget-me-nots in Flora’s hair, some with five petals, some with six, or strawberry flowers?

The yellow flower by Mercury’s right foot looks to have the leaves of the flax plant (linum usitatissimum), the flowers of which are in fact pale blue.

And other plants are similarly transgressive, showing discrepancies between leaf and flower.

The meadow might be a fragment of a diagram of total-plant-space.

– PRIMAVERA,

SANDRO BOTTICELLI

A good taxonomy is sensitive to the quiddity of cases[5] : the cases amplify or subtilize the taxa, indicate how they overlap, are differentiated, contiguous.

There is a sort of sanity in identifying the stuff of the world. And the sanity is in part owing to the devotion deferred. We are not, in looking at the Primavera, seeking audience with the dark queen, entering a pictorial space like that of a Byzantine icon; we are not (for all that Ficino perhaps thought we should be) in thrall to the presence of the object, or to the illusions of space spun within it. Rather, our eye wanders through it, around it, as though strolling in a republic or free association of detail. The detail relates to the whole, but is also in some key ways independent of it. It is loosed from the gravitational suck of the pattern.

The gesture of the Venus at the centre of the painting, incidentally, is one of welcome.

In Star Trek: Voyager, Kes, an Ocampan, creates an airponics bay in one of the cargo holds, in order that the crew can have a rolling supply of fresh vegetables. She also grows cut flowers.

Kes has powers that are recognisably magical. She is Voyager’s witch, its sorceress, an ambiguous telepath who can heal by touch alone and is in tune with the psychic energy of the crew. Usually benign (but in one episode positively malign), she is overcome at the beginning of series two by the Ocampan reproductive cycle (the Elogium) in which she displays stereotypically irrational appetites:

The Madonna in quattrocento art, I am beginning to understand, is a sorceress, a mortal who couples with winged gods, a fairy queen bewitching the space in which she is represented and the Saints who are in her thrall: Lucy with her tray of eyes, Lawrence with his gridiron, Sebastian with his piercings, Hunter Sidney with his array of scientific orchids.

No wonder I dare not look her in the eye.

The next day Mrs Isobel Easter casts an eye over the plants I have brought—ornamental bitter fruit, cyclamen, a dog rose—and then takes me through the garden by narrow paths, pushing between the knee-high, chest-high overhanging shrubbery, trailing her hand in the greenery, pointing out this or that, telling me where I can cut back, where a given plant will thrive.

Mrs Isobel Easter, it turns out, knows each plant in her garden individually, by name (in some cases common names, in some Latin). She can tell me something about their history and provenance—not the history and provenance of their species, but of the individual specimens.

This is disconcerting. I have only ever seen in this garden a clotted mass of green stuff, interesting for its broad organisation, its allegorical patterning, but unreadable in detail.

She is telling me how she came by various plants, providing horticultural notes, but she might be talking me through the magical, medicinal properties of forest flowers and herbs (hartstongue for paralysis, saxifrage for ailments of the throat, carraway against scorpion stings). The vision of taxonomical certainty which I had entertained in Emmet Lloyd’s Cobham Ur-Nursery is suddenly, entertainingly, in some disarray.

– PAGE FROM THE PSEUDO-APULEIUS HERBARIUM,

IMAGE: BIBLIODYSSEY

Not that I expect to find her eating beetles, or for that matter humming ancient airs, or dancing with the Graces, but something has changed in my perception of the garden, as though I have momentarily slipped my cognitive moorings and am now navigating by periplus around islands and reefs of plants, actually occupying a space I have only previously imagined, one replete with newly individuated matter; and I have a guide.

In Total-Plant-Space there are certain plants which have the attributes of Ideal Forms, and these are the cultivars. A cultivar is a stable variety of a given plant which will reliably transmit its various desirable characteristics through propagation. Whether in their origin or in their continued and refined stable form, they are the products of cultivation. You might say they are plant forms which have been winnowed by and assimilated to civic life, in that they are public and communicable objects of gardening.

Similarly in Total-Art-Space there are stable hybrids. We have seen how representations of the Annunciation were organised around the four micro-stages of the story as related in Luke. There is in fact a fifth Laudable State which follows immediately on the departure of the angel, known as meritatio. This is associated with images of the Virgin alone, known as the Annunziata, as for instance here:

– ANNUNCIATA DI PALERMO,

ANTONELLO DA MESSINA

Antonello da Messina had travelled in the Low Countries, where the chromatography of art history was throwing up different categories, among them a genre of intimate, non-aggrandizing portraiture, to which the Annunciata properly belongs. It has its iconic properties, but the Virgin here is a fully human specimen: not a magus, not a prince, not a witch. Not, it could be added, a Virgin. And, to my relief, I can see her face.

By the end of the sixteenth century, the century in which the importation and development of decorative cultivars to North and Western Europe in particular transformed gardens from allegorical or functional spaces into aesthetic, decorative ones, the representations of plant life had similarly separated themselves from the dominion of historical or devotional art (narrative frescos, altarpieces). Plants were now foregrounded in botanical illustration and still life.

We are witnessing, I would contend I think uncontroversially, a drift towards the individuation of exempla. And while I may, paradoxically and typically, have expressed that as an overarching and megalomaniacal theory of everything, its purport is clear: Norbiton is an accumulation of individuated detail, and life in Norbiton a continual repatterning of that detail.

E.H. Gombrich in The Sense of Order talks about the horror vacui of non-Classical craftsmen, their need to fill every void created by a line or tendril or a foliate form with another, branching, line or tendril or foliate form, and so on to the limits of the visible or the tolerances of the tools and materials. He suggests that this impulse should be renamed amor infiniti.

– CHI-RHO MONOGRAM,

LINDISFARNE GOSPELS

My book was called The Roots of Ornament, but I see now that it should have been called The Rootlessness of Ornament. It should have dilated, not on the profligate dalliance of ornamental motifs, the mystifying multiplication of geometrical pattern, but on the paradox of their spontaneous generation. An ornamental field is an infinite, irrational decoration. It is an insane restlessness; it is defiant of rest. The eye never comes to a stop, looking at ornament; nor, properly speaking, does it ever start. It merely pitches in and is tossed about.

A garden, unlike its decorative analogues, is an assembly of actual rooted objects (plants). These plants can be placed not only physically, in Garden-Space, but also accurately in phylogenetic relation to all other plants, whether they are real, extinct, logically necessary, or untenable but thinkable. They are precisely, if for practical purposes unknowably, located in Total-Plant-Space. And they are, I deduce, to a restless mind a repose. The strolling God was at ease in an Eden that was infinitely extensible, properly known, and rooted in time and space.

There is a dilapidated greenhouse at the bottom left of Mrs Isobel Easter’s garden, its white paint blistered and miscoloured, and its glass where not broken stained with residual chlorophyll and the archaeological spatter of rain. It is narrow, with slatted benches on two sides and a raised brick bed on the third; the fourth is mostly the door. It is littered with broken potsherds, dead yellow stalks of old tomatoes, torn and empty seed packets, gutted plastic remains of compost bags, dried out bottles of tomato feed, rooting compounds and powders leeched to dust; and it is home to large spiders.

This, I decide, is where I will take my stand against rootlessness. At the heart of Mrs Isobel Easter’s garden of amor infiniti, horror vacui, I will build a small hidden generator of plants. I will drive back the spiders, brush down the surfaces, repair the frame, and start to investigate propagation, from seed, from cutting, from rootstock. I will make small experiments. And between this place, the two gardens I work on, and my allotment, I will establish, not a rational city, but a daily economy of empirical enquiry.

Footnotes ☞

1 ‘I think the carrot infinitely more fascinating than the geranium. The carrot has mystery. Flowers are essentially tarts. Prostitutes for the bees.’ Bruce Robinson, Withnail and I ⏎

2 after Baxandall’s discussion of Landino in Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy p.122 and 131: ‘To Landino, Filippo Lippi and Fra Angelico’s paintings were ornato, where Masaccio was without ornato [i.e puro] because he pursued other values. That is to say, Lippi and Angelico were piquant, polished, rich, lively, charming and finished, whereas Masaccio sacrificed these virtues for clear and correct imitation of the real.’ ⏎

3 ’The system indicates the plants, even those it has not mentioned; which is something that the enumeration of a catalogue can never do.’ Linnaeus Philosophie Botanique sect. 156 ⏎

4 4 in Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy, 1972 ⏎

5 “The relationship between the minute precision of the work and the proportions of the sculptural or intellectual whole demonstrates that truth content is only to be grasped through immersion in the most minute details of subject matter.” Walter Benjamin The Origins of German Tragic Drama 1928. I get all my information about the flowers in the Primavera from a review by Charles Dempsey in the Renaissance Quarterly ( Vol. 37, No. 1 (Spring, 1984), pp. 98-102) of Mirella Levi D’Ancona’s Botticelli’s Primavera: A Botanical Interpretation Including Astrology, Alchemy and the Medici (1983). I’m amazed I found the reference after all this time, and it’s just as well I did: personally, I can’t tell one flower from another, unless it’s maybe a daisy or a dandelion. ⏎

Anatomy of Norbiton on HILOBROW

Original post at Anatomy of Norbiton: Horticultural

Anatomy of Norbiton

Short Life in a Strange World by Toby Ferris

Toby Ferris on Twitter

On the Paintings of Pieter Bruegel by Toby Ferris

All tapir illustrations by Anna Keen: portfolio