Norbiton (17)

By:

March 26, 2021

Anatomy of Norbiton: Fantastical

‘According to Hilaire Belloc, bystanders at the burning of Ridley and Latimer were heard to remark that is was a pity that this burning had not been performed earlier in the season, as then it might have saved the crops.’

Lady Raglan The Green Man in Church Architecture (1939)

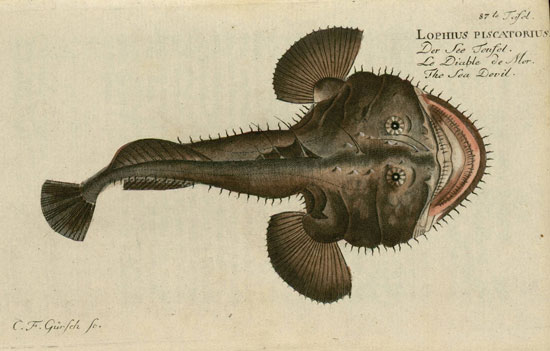

LOPHIUS PISCATORIUS – FROM OEKONOMISCHE NATURGESCHICHTE DER FISCHE DEUTSCHLANDS 1781-3 M.E. BLOCH

IMAGE COURTESY OF PEACAY AT BIBLIODYSSEY

The Ideal City exists in fact, but its various elements are held in place by the mind of its citizens.

Should this collective mind lose focus, the intersecting planes of the City’s incorporated body, its projects, its places, are apt to sheer apart or collide, its particular pattern of civilisation gradually disperse or crumple.

This much is true of any civilisation; you might say, of any city, any place.

Paradoxically, however, if the city is to grow, to move, to change – in short, to exist—then its articulations are likely to come under just this sort of stress. The corporate body will change in detail, the personnel of the city will alter, there will be flow, mutation; the roots of institutions will warp the foundations, the grip of the mind will shift, gradually slip.

The Ideal City, in other words, wants not just structure, clarity, order, if it is to flourish; but a sort of mechanics or differential, a certain give or play in its elements.

To say so, however, is to acknowledge not just the beauty of its tectonic foundation, its archipelago charms, but to understand that islands—actual, psychological, ecological—are spurs to differentiation. Commonplace mutations accrue significance, weight, sharpness, and in time the animating principle of the city will be expressed in an evolved monstrosity.

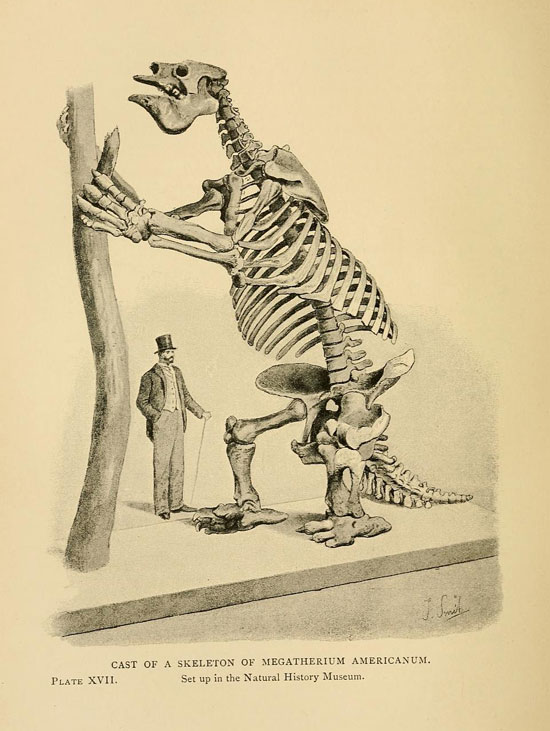

MEGATHERIUM – FROM EXTINCT MONSTERS; A POPULAR ACCOUNT OF SOME OF THE LARGER FORMS OF ANCIENT ANIMAL LIFE REVEREND H.N. HUTCHINSON

IMAGE COURTESY OF PEACAY AT BIBLIODYSSEY

Monstrosity is characteristic of margins—monsters are intermediate forms, placed between two or more known forms. Thus we have sphinxes, wyverns, gryphons, centaurs. But it is a form on display. You show a monster to the people, the curious, perhaps paying public. A monster is a demonstration of deviance.

In the middle ages, marginal forms—forms dwelling on the exteriors of buildings, or in the margins of illuminated manuscripts—are by nature fantastical, monstrous. Monsters are like irrational numbers, proliferating without end in the interstices of reality; whatever form can be imagined, it is always possible to extend it, warp it, add a horn, a finger, subtract an eye; there is always one step beyond, one more degree of monstrosity.[1]

Intermediate forms are the product of a crude dialectic, a child-like mixing of elements. We ourselves, the Cyclopes of Norbiton, are in this way the product of forces to which we are not party; we are the marginal monstrosities of other places.

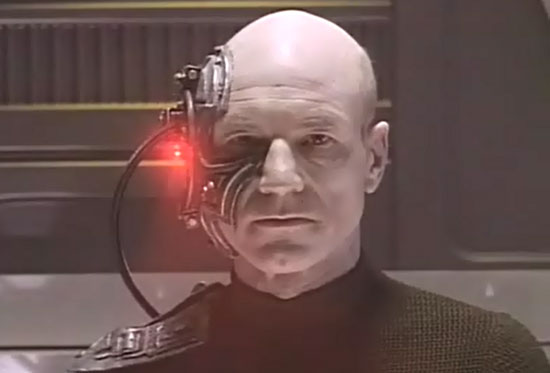

But we are equally and inevitably the central monstrosities of our own monstrous place, fantasizing our particular mutations, our gravid translation; thus Clarke is a Green Man, brute and amoral; Hunter Sidney a Borg, implant-ridden and mechanical; Solomon is a scrivening dwarf, Cannoner a Frankenstein, Nestor the Blind Argentinian a monster of the deep, compressed, bloated and bilgy; Emmet Lloyd a barking fool, and I, in the gaseous formlessness of my days, am all belly, all rot.

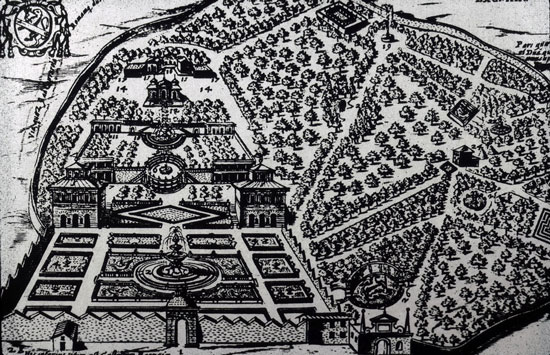

The formal gardens of the cinquecento were typically juxtaposed with informally planted groves and woods, known as boschetti,[2] in what can best be described as a rhetorical balance of elements.

This balance has been lost sight of over time, as the more vulnerable boschetti have been torn up, replanted, given over to other uses. The gardens of the Villa Lante at Bagnaia, for instance, sixty miles north of Rome, are usually considered as an example of formal terracing and harmonious hydraulics, but these were just elements in a broader patterning comprising also the Villa itself (where, mining its walls as it were, was located the grotto of Apollo and the Muses) and the selvatiche of the surrounding hills, which in turn were dotted with the sort of statue groups generally associated with the more formal space.

PLAN OF THE VILLA LANTE

These gardens were (not unreasonably, given that gardens are apt to grow, to change with the season, the light, the time of day) richly metamorphic spaces. Ovid was the great poetic presence of both the quattrocento and the cinquecento,[3] his writhing and self-transforming Metamorphoses, in which story emerges from nested story, underpinning – you might say, formalising—the Renaissance perception of an animated universe where all matter was in a continual state of flux, taking form and passing out of form. Thus the statue groups of the selvatiche of the Villa Lante were of a Unicorn, a Dragon, Bacchus and his train.

In creating this more precisely articulated space, the architects of cinquecento gardens detached the viewer from his vantage point and set him spinning in time. Whereas in the quattrocento a garden could be understood as a perspective view from a fixed spot, in the cinquecento the viewer was forced to make temporal passage from room to room, statue group to statue group, grotto to grotto, a sequence of experience more or less determined in order, more or less surprising.

Thus in attempting to manipulate sequence, to hold the formal in fixed relation to the informal, the created to the ‘wild’ or emergent, to build a formal structure, in other words, expressive not of disorder but of the varieties of order, the architects and patrons of the cinquecento succeeded in marking out discrete spaces and making each one a term in a rhetorical progress,[4] creating not just the conditions for disagreement and disputation but a culture of borders that must be crossed, that demanded to be peopled with grotesques, fantasticals.

And it is not just the statue groups in the boschetto that are given over to this stage-managed Ovidian transformation; the viale become viottole, the column orders of the villa revert to their originary trees, the pediments to the thatch of the capanne which dotted the rustic hillside.[5] And a cardinal becomes, in play, a Green Man, a wild spirit, a presiding deity, wandering freely among his tame monsters.

The allotments of the Kingston Road, by contrast with the gardens of the cardinals and princes of the cinquecento, do not constrain or encourage movement, are not a pageant or royal procession; but they are composed according to a logic of spatial and temporal fracture.

Each citizen has his strip which is given over to its own patterns of planting, of neglect, of history. Each strip in turn abuts the next, without the smoothing of translation. Only an expert or familiar eye will discern the viale or viottole from the cultivated ground. As you walk through them, among them, between them, each in its own stage of growth, priapic or flourishing, dying back or etiolated; as you nod to your peers, glance at their emblematic activity – digging, hoeing, sieving, watering, so many tableaux vivants, allegorical assemblies; examine their particular disposition of cut flowers, vegetables monstrous or apologetic, their primitive architecture of shed, trellis and beanpole; as you, in short, move across this fertilized land, you might be moving from room to room of some arcane memory theatre where the stages of a life are analysed out; you see here the young, the old, the beaten, the wise, the male, the female and their material spore. As though this were all one animating life, one space, but compartmentalised, divided, in some manner understood.

NORBITON ALLOTMENTS

It is June, the High Renaissance of the Norbiton allotments, and on a weekday morning I stand looking over my own tract, my beans and potatoes and unkempt fallow fringes.

And my allotment, I note wearily as I gird myself to deal with the interlopers and pests, is not without its share of monstrous intermediate forms.

What is the natural extent of a human sphere of possession? A valley? A mountain?

Our spheres of possession are typically compressed or restricted or distorted by those of others. We sit in our back gardens, for example, behind our walls, in our compressed atom of space, abutting other identical gardens which we never really see.

In certain monstrous circumstances—those of a King, for instance, or a prophet—the sphere of possession extends to embrace, if that is the word, a kingdom, earthly or otherwise; and is consequently diffuse, imprecise, nebulous.

But for those cardinals and princes of the cinquecento in their gardens the sphere of possession lay somewhere in between, grounded for real in known places which they could affect, if not to the millimetre or the inch, then certainly the square metre or the acre.

Were we each permitted by circumstances to allow our sphere of possession to expand to its rational limit, it would fill a space, I suspect, of roughly one cardinal’s garden, and would comprise a horizon. It would be an epiphany of our better minds: a limpid, complex geometrical object through which lively and agreeable airs pass, enlivened by abundant geysers of water, contrastive shades, scents of fruits and flowers.

But instead, these spaces are peopled by paunchy and tyrannical cardinals and princes, who bring the darkness of their stultified ambitions along with them, and probably kick their gardeners for sport.

In NORBITON: IDEAL CITY we work to a smaller scale. We do not admire or envy the workings of privilege: the rich, the wealthy, the powerful have merely exhausted one line of enquiry, and to us they occupy marginal spaces, are bloated monsters beyond the ring of light.

But as rational citizens we are forced to ask, in common with them, what does it mean, not just to be in a space—allotment, vast garden, city—but to take full possession of it?

I do not have a ready answer. I get on with my weeding and digging.

A hundred yards away Clarke is sitting unseen in his shed, drinking his thermos of tea, watching Gardener’s World on his laptop, exchanging words with passing fellow gardeners, sheltering from the mild noonday sun like an anaemic white pope or doge who in giving audience, in saying little, garners power.

Eight miles from the Villa Lante are the villa and gardens of Bomarzo, which in an inversion of the usual pattern has retained its boschetto rather than the formal gardens through which they were approached.

The boschetto, known in the lifetime of its creator Vicino Orsini (1523-1583), as the Sacro Bosco, now stands isolated in woodland below the hilltop villa. Like any boschetto, its walks and dark paths are punctuated by temples, follies, statues, fountains; unlike any other boschetto, these features are carved for the most part directly into the huge outcrops of peperino rock (lapis albanus) that jut from the hillside.

The allegorical or emblematic system of the garden has for the most part resisted interpretation. There is an elephant with a tower, a tortoise with a statue of fame on its back, a giantess with a pot on her head, a monstrous hell mouth, a giant rending a prostrate foe, a false Etruscan tomb, a leaning house, a sort of dog, a sort of dragon, and so on; all polychrome, gnomic, misplaced.[6]

– DRAGON AND LIONS, BOMARZO

PHOTO: ALESSIO DAMATO (OWN WORK) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (HTTP://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY-SA/3.0) OR GFDL

(HTTP://WWW.GNU.ORG/COPYLEFT/FDL.HTML)], VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The managed wood with its paths and walks which gave point to these disparate objects, no longer exists in its intended form. Approached through the rational ambulatory of the formal garden with its rectilinear paths and planting, the Sacro Bosco, it seems from contemporary accounts, was a hyperfractured maze of short avenues, twisted viottole, arrhythmic, stuttering passages from one statue group to the next, sharp and unforeseen breaks in level. The long vistas and organising perspectives of more typical cinquecento gardens, with their architectonic use of topographical irregularity, have given way, or you might say collapsed into, the grimly playful logic of entanglement, enchantment.

For centuries after the decline of the Villa and the eradication of the formal gardens, the local people held the boschetto, now become a veritable bosco, in terrified and superstitious awe. It was an abhorrent place. Those playful monsters of Orsini, designed to delight and surprise (and probably baffle) his dinner guests (including, regularly, his friend Cardinal Gambara of the Villa Lante), were now become monsters proper: overgrown, mossy, eroded, tenebrous.

– HELL’S MOUTH, BOMARZO

PHOTO: ALESSIO DAMATO (OWN WORK) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (HTTP://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY-SA/3.0) OR GFDL

(HTTP://WWW.GNU.ORG/COPYLEFT/FDL.HTML)], VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Latterly, cladistic taxonomy has, if not done away with, then problematised intermediate forms. Everything merely is, stands in its place in total-creature space. In the same way, the Sacro Bosco is now become the Parco dei Mostri, a sanitised curiosity, with paid admission guaranteeing the sedateness of the monsters.

But the local people and the Renaissance still knew what we have shaken free of: that monsters are warnings, from heaven or nature. Monstrous births, deformities, conjoined species, are signs of the mutability of the cosmos, its quantum uncertainty, mapping like a double-slit experiment the shifts in form that afflict matter.

For the Renaissance this mutability was a paradoxical force. The world was in a continual flux of creation, but its proper forms were immutable, given. Small wonder that the Bible, like the Metamorphosis, has multiple creation myths. A monster could be not only a sign of the mutability, a warning of some instability manifesting itself or about to manifest itself, whether earthquake or the collapse of a kingdom, but also a protection against it, a talisman, a lightning rod, an apotropaic presence. Either way, it was to be respected.

In the case of the enchanted wood at Bomarzo, the local people were right to be afraid. In those mossy overgrown tortoises and elephants lumbering with their pointless burdens through the forest, they could contemplate a vision of the residue of consciousness, what is left, so to speak, of a cardinal (or in this case a prince) when he dies: a pointless riddle, a tedious confused babbling remnant, a terrifying disjunction of objects and the ill-recalled stories that seek to connect them. A reminder, if nothing else, to carve nothing in stone.

NORBITON: IDEAL CITY is thus forewarned in the Sacro Bosco, and more subtly in the gardens of the cardinals, of its own fate: a City overcome, grottified; it is a tectonic landscape, the plates and locales shifting, nudging imperceptibly but unopposably into one another: Cannoner’s lock-ups abutting Old Sol’s library, Kelley’s garden rising like a Himalaya over the subduction of the allotments. Moving from one to the next involves the crossing of invisible ritual boundaries, the vivifying principle that informs them all (call it an idealism) not only animating, but distorting them; they grow, mutate, change; a perpetual intermediate form.

In the early summer of the Ideal City, without yet realising that our collective sphere of possession was already compromised, that it would ultimately require almost daily mapping and remapping, I moved methodically from room to room, generally working on my allotment or in Solomon’s bookshop in the morning, and, hijacking Solomon’s van, on my various gardens in the afternoon.

Kelley’s garden was my Bomarzo, with its jungle strangeness, its loping canines, its screeching parakeets, and its two laconic cement objects—one a statue of Venus/Mercury (eroded to illegibility), the other a dry flat dish fountain; each about four feet high and now much overgrown, concealed. I had also latterly come to endow the garden, in my head, with qualities of Etruscan atavism—a sort of wild and persistent undergrowth emerging through the ruins of a more rigorously ordered, but as it transpired, transient planting regime.

Mrs Isobel Easter was still bringing me hourly tea, and so leaning on my spade and cradling my mug I tell her on this particular afternoon about the Villa Lante, and Bomarzo and the Etruscans, and wonder aloud what an Etruscan garden might have looked like, speculate that there would have been trellises and vines, perhaps other favoured flowers and herbs unkempt and vigorous, and spaces demarcated for banqueting. Mrs Isobel Easter agrees—how could she not?—that neglect has its own beauty, its own aesthetic system, and acknowledges that over the years she has watched the advance of the animating spirit of the garden against the forces of order with the pleasure of release and dissolution. And then without any other preamble she invites me for the first time inside the house and up to her rooms, to view, as she puts it, a curiosity.

While Isobel rummages for her curiosity, I lean over the desk (actually a broad table) and get a view of the garden.

I can see from this vantage two things which I had not noted before: that a stretch of high wall at the extreme bottom right of the garden is the park wall (Richmond Park); and that the garden is tendentially elliptical rather than quadrilateral (albeit highly distorted), with the statue and the dry fountain (actually invisible) standing not only more or less at the twin foci of the ellipse, but marking also significant breaks in height in the garden, both axially and transversally (the house and the bottom left of the garden are up; the right and bottom right of the garden are down).

It is not surprising that the confusion at ground level is resolved somewhat from above. Structure emerges with distance. A river that flows North to South will close up be an unreadable series of eddies and turbulences. It has been said, similarly, that the rhetorical structure of the Renaissance garden was a way of ordering the experience of it, of stepping back from the perceptual flood into the clarity of a rational space. In the same way we codify our raw emotional or perceptual responses into sentiments which are a medium of exchange; sentiments can be further aggregated into, for instance, the sentiment cluster which we can designate peaceful remove in a garden.

I am slightly nonplussed, however, that my Bomarzo, my irrational garden, should have a history visible from the air like medieval fields; and, maybe more so, that it is subject to perspective.

Those Renaissance gardens had their long viewpoints, after all, their vistas; as you moved through the space it unfolded itself to you in revelatory views, and I suppose it is true that these vistas were more than simply invitations to gaze: they were both organisational – developing, for example, the axial relationship of garden to villa, allowing you to unpick the ordo from the copia, as Alberti would have had it, to see the wireframe beneath the ornamental bitter oranges, the cornelian cherries – and conduits to contemplation, properly understood.

The word contemplare, often used in the sixteenth century to indicate one of the functions of a great garden, is never used to mean think or meditate in the abstract; it always means hold something in view, look on something—a statue group, a nymphaeum, a cascade. Contemplation suggests visual fixity; a lightning rod to the flickering, dispersed perception otherwise proper to a garden.

I believe, or have believed, that if I could establish a high enough pitch, I would see NORBITON: IDEAL CITY as a limpid point in space, and it would become available for contemplation, an abundant source and epitome of clean geometry, a rhetorical and actual locus of precision, potential, citizenship, understanding; and not, as now, as a fractured unreadable landscape, a tessitura of alleys and rooms and points and faces through which I wander like some mumbling and confused prophet, fretting over my anatomical Jeremiad which with each word, each renewed attempt to clarify and sharpen, only grows bigger, more abstruse, more chaotic, a confusion grown to drunken consciousness, a monstrous emergent jabbering Entity.

Of more practical use, perhaps, I also notice from Isobel’s window that a piece of guttering I have fixed in a tree is catching the light, is visible. Isobel is privy to the mechanical exploits of the rain garden.

At the end of the third season of Star Trek: The Next Generation, Picard is assimilated by the Borg and ornamented after their fashion with prosthetics and implants. He becomes their spokesman. To his colleagues he is now a hyper-monstrous presence, translated in front of them into the playful intelligent essence of cyborgiana, and he must be destroyed.

What can we suppose that Picard learns from this monstrous dabbling in collective clarity? The Borg, unlike the citizens of the Federation or, for that matter, the Ideal City, are chasing a form of perfection from within a gross accumulation of matter—a perfection which lies outside and in front of them, which they will construct themselves.

Not unlike the Federation, in its way.

The fact of the matter is, Ideal forms—Federation, Borg Collective, and, I miserably suppose, IDEAL CITY—have nothing to do with all this mutability, this gloomy inevitable process: what we might call stuff actually happening. Form emerging from the mud and soup of matter is not answering to an Ideal Platonical template. It is speculative, improvised, playful perhaps, certainly dysteleological. But never, by definition, monstrous.

Picard is eventually rescued, and after his implants and tooled limbs and the whole filigree mechanics of Borg perfection have been removed, he returns to duty. But he has now found his White Whale, disporting itself in mute calm deep within him.

Footnotes ☞

1 It has been argued that this medieval aesthetic prepared the Renaissance mind, and in particular the cinquecento mind, for the proliferation of intermediate forms characteristic of what became known as the grottesco, the candelabra sprites and beasts of the Roman frescoed halls of the Domus Aurea, which spread through Europe after their discovery in the 1470s. ⏎

2 Or, when planted especially thickly, ragnaie, (meaning, I suppose, spidery; a spider’s web is a ragnatela); or sometime selvatiche, wild places. ⏎

3 As Virgil had been of the trecento; similarly, the Renaissance loved Petrarch, not Dante. ⏎

4 Their structure, it has been noted, is like a pageant, a series of floats, akin to the experience of Royal entries, processions; the grotesque floats of the carnival. ⏎

5 In his Zibaldone or commonplace book Giovanni Rucellai diffentiates the terms in which he describes the wild and subdued arenas of his garden (at the Villa Quaracchi, notable for its formal planting and its artificial mount), among them those for paths, as here; perhaps this indicates a memory of a conversation with the architect of his gardens (reputed to be Alberti, the architect also of the Palazzo Rucellai), a dutiful replication of terminology. Rucellai, it should be noted, was writing at the end of the quattrocento. ⏎

6 Originally painted (white, red, rose, blue, faded yellow, and yellow-green according to a letter of 22nd December 1573, to reflect the colours of the Orsini arms), now mossy, stony, belichened. ⏎

Anatomy of Norbiton on HILOBROW

Original post at Anatomy of Norbiton: Fantastical

Anatomy of Norbiton

Short Life in a Strange World by Toby Ferris

Toby Ferris on Twitter

On the Paintings of Pieter Bruegel by Toby Ferris

All tapir illustrations by Anna Keen: portfolio