Norbiton (14)

By:

March 5, 2021

Anatomy of Norbiton: Emblematic

– INFIDELITY, GIOTTO, CAPELLA SCROVEGNI, PADOVA

Is NORBITON: IDEAL CITY best understood as a puzzle to be solved, or as a chequerboard of possibilities?

We take for granted that the latter is invigorating. There are more, if not quite infinite, degrees of freedom. You can ponder your move, build your pattern, muster your strength, worst your enemy. And there is no single solution. There are many paths to victory, some dogged, some ruthless, some heroic, some beautiful, some nefarious. And while some of those paths lead to failure, there is always another game. The general possibility saves you from the particular concatenation of events.

The former, in contrast, appears limited. There lies the grid in front of you; its answers may be concealed, but they pre-exist, are inflexible, invariant. Once you have found them, they are yours forever, for what they are worth; if you do not find them, then they can be revealed to you just the same. Or not, as the case may be.

Renaissance Italy was found of its games and puzzles in equal measure. Life was a game but the cosmos was a puzzle. Games, then, whether chess, rithmomachia, or altarpieces and frescoed chapels, were grumbling, worrying, ruminative pursuits, not unconnected with the ambiguities of your personal salvation; puzzles – rebuses, emblems, imprese, glyphs – suggested that arcane truth could be accessed with the right combination, and accessed once and for all. The obelisks of the Egyptians, the writings of Hermes Trismegistus, the doctrine of natural sympathies and the talismanic potential of stones and harmonies, were so many cosmic nuts to crack.

To repeat, is NORBITON: IDEAL CITY a puzzle concealing an arcane truth; or a balanced disposition of elements, which we engage with afresh each day? Which is it? Emblem, or art?

Hunter Sidney is about to find out. He is about to be emblematised. We have him sat back to front on a chair, shirt and vest off, his flesh, blotched, sagging, pitted, flaking and vulnerable, offered up for our contemplation. He is getting a tattoo. And not just a tattoo, but an emblem.

The emblem is a composite literary/artistic device which was popular – immensely, puzzlingly so – from the sixteenth century on.

In its standardised form, it is a tripartite design comprising motto, woodcut image, and discursive text or poem (inscriptio/motto/lemma : pictura : subscriptio) which interact to explicate, typically, some moral commonplace or other.

The originary emblem book, the Emblemata of Andrea Alciato, a Milanese jurist, was first printed in Augsburg in 1531 (unauthorised) and in Paris in 1534 (authorised, Christian Wechel), and then, after innumerable reprintings around Europe, in Venice in 1546 in an expanded edition by Aldus Manutius. It established the template for what was to be a protean form, and stayed in print for 350 years.

Ernst Gombrich remarks somewhere that while we have no difficulty associating written word with musical setting, we have to make a considerable leap of the historical imagination to understand the linking of word and image. But about emblems he is correct: the emblem is not only a defunct form, it is an alien one. We do not like them. We do not like anything about them. While they are playful, they are not in the least funny, and not, properly speaking, ludic—there is no sense of Saturnalia, of the carnivalesque, about them.[1]

Renaissance emblematics, in short, is a dry brittle science, like a desiccated songbird; pick it up by its hooked toes; it weighs nothing.

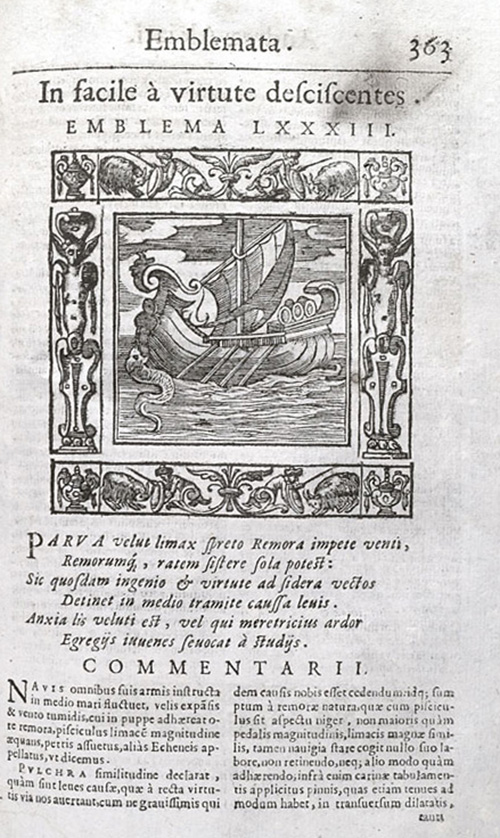

As an example, we can take Alciato’s emblem no. 83.

– EMBLEMATA, ANDREA ALCIATO PETRO PAULO TOZZI (1621)

Against those who fall easily from virtue

“Small as a snail, the remora is able by itself to stop a ship. It’s disdainful of the force of wind and oars. So some petty circumstance can check in mid-career certain men who are, by genius and by virtue, headed for the stars. Likewise a tormenting law-suit, or a passion for a prostitute, draws youths from their distinguished studies.”

The remora is a parasitical (or better, commensal) fish which locks on to a host (a shark, a turtle, a manta ray) and feeds on scraps from its host’s table, as it were, or on their faeces. It was popularly believed to attach itself to ships in the same way, acting as a drag anchor. Pliny the Younger notes that the actions of the fish led to the defeat of Mark Anthony at Actium, retarding a key ship at a decisive moment.

By contrast, the relationship between woodcut and epigram is not commensal (or parasitic) but ostensive. Each points to the other, clarifies the other, focuses the other. The same is true in varying degrees of the motto and the epigram and the motto and the woodcut.

Whether, however, that ‘pointing to’ is a neutral act is debatable; it seems to me that the three parts in Emblem 83 do not mutually inform so much as interfere with one another. There is, if you care to think about, a lively internal friction – the motto does not relate all that naturally to the epigram (Are we discussing the small chances of life that bring failure? Or the habitual (thus moral) failings of the failed agent?); the woodcut seems plain enough until you register the whale-like size of the fish that is hampering the ship; the epigram itself veers between the portentous and the inconsequential.

Emblems, we might conclude from this admittedly limited sample, are like a fish market of meaning, shout and counter shout. But perhaps we should take Emblem 83 at face value for a moment and allow the implicit connection between the apparently fleeting impedimenta of life and the moral failings of the impeded agent.

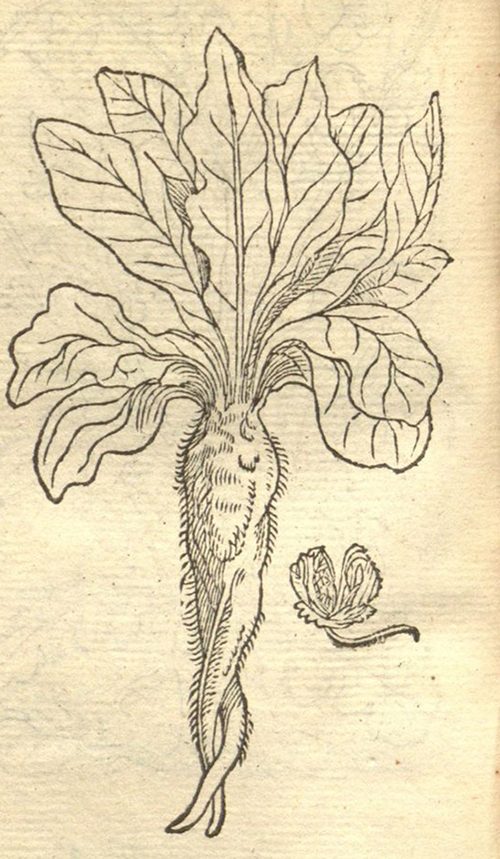

Hunter Sidney does not want a tattoo of a commensal fish. He wants a tattoo of a mandrake root.

– REMBERT DODOENS, CRUYDEBOECK 1554

We are four in the room. Hunter Sidney, Clarke, Mandy, Clark’s girlfriend, and I. Mandy is a hairdresser, but can turn her hand to tattooing, it turns out. She is sitting behind Hunter Sidney, needles at the ready, casting her eyes this way and that. Mostly that.

There is a certain disagreement about the status and nature, and therefore the progress, of Hunter Sidney’s tattoo. A disagreement which crystallises in Hunter Sidney’s remark that he does not wish to be[2] emblematised.

Clarke is stretched out on the sofa, nursing a cup of sweet milky tea. We have already inspected his tattoos. The design is inexpert – they were started by an artist friend in Rome, and finished by his girlfriend Mandy, who not only completed the design and provided the inscription, but also stretched her more ornate and uninhibited hand over the hesitant scratchings of her forebear or, as Clarke puts it, freshened them up – in short, the tattoos are not a particularly pretty sight.

However, they have a clear emblematic status. They are located in a cluster over his left shoulder blade, and are underwritten by a brief motto-like inscription, homo, fuge! They are, in order, an Egyptian ankh (although Clarke calls it an’omunculus), a lithium atom – both the work of his artist friend in Rome – and an anchor.

He talks us briefly through his bastard heraldry. The ankh, he says, stands for the vita comtemplativa (as explained to him by his Roman friend); the lithium atom is the ‘material basis of life’ (lithium, because three electrons worked better than, say, one, or seven, although at first glance the design resembles a childish flower); the anchor nods at the impresa of the Aldine press and its motto, FESTINA LENTE;[3] but the motto, scrawled underneath in a sort of cod Gothic script, is HOMO FUGE!, taken from Marlowe’s Faust: it appears in his congealing blood when he signs away his soul. Clarke seems to interpret it as a general lament on the restless of his life (‘omunculus fuge!).

– TITLE PAGE OF FLORILEGIUM DIVERSORUM EPIGRAMMATUM (1503), DETAIL

He pulls down his T-shirt. I ask him why, if he was moved over the years to scratch an indelible emblem into his flesh, did he put it in a place where he could never see it; he responds by mildly pointing out that he never sees his arse either, but is secure in the knowledge that it is at large and doing good work in the world of signs.

I had been wondering (aloud, as it happens; hence Mandy’s hesitation, and Hunter Sidney’s little snap); that Hunter Sidney’s emblematic imagination did not run a bit further than a mandrake root.

He might, for instance, think about emblematising the Ideal City itself. Although in fairness to Hunter Sidney, to emblematise a multiplanar city or any other complex object would require not a solitary image but a number of swift passes, not an emblem only but an emblem book.

Hunter Sidney, leaning over his chair, asks if we haven’t already undertaken as much in designing and rearing up the Ideal City and in particular the Anatomy of Norbiton? And adds that perhaps his shoulder could be left out of account.

If I am to infer from his remark that he considers empirically real cities to be Anti-Emblems (spaces characterised, in other words, by an exhilarating plasma flow of fragmentary images and epigrams and mottos and commentaries), and Ideal Cities to be coherent and articulate and eloquent and above all UNIFIED emblems, then I would provisionally concur; but I would add that there is in every body of space a coagulating impulse, and consequently there is always a need for a little more finesse, some finer slicing, some more telling cut; there is – what it really comes down to – the unspoken quest for the emblem of all emblems – not a universal emblem, to be clear, but an emblem that might serve, if you like, as a rough pitch for the whole project: an emblem that answers the question, what is this [Ideal City, Anatomy] all about?

But Hunter Sidney, after the room has digested my suggestion in silence for a moment, says only, does the emblem of emblems need to be on my shoulder?

I should pause at the point to clarify that neither Clarke’s tattoos nor Hunter Sidney’s, nor what I have called the emblems of the Ideal City are emblems, strictly understood: they are closer, in total-emblem-space, to the region of what are called devices, or imprese. An impresa was, among other things, personal to an individual rather than general to a moral problem, and was typically bi-partite (motto and image) rather than tri-partite.

Needless to say, the taxonomy of a dead art is scarcely relevant to our current purpose: what is relevant is that both Clarke’s tattoos and the devices of Norbiton and much else in the Ideal City besides, derive from an emblematising sensibility.

The moment you choose to write something down, or chisel it into a block of wood, rather than let it float by and mutate and collide with other possible ideas in total-idea-space, is an emblematic moment akin to the minting of a coin or the shaping of a block of stone. The idea is liberated from the ether of possibility, and brought into the cut marble of actuality.

Marble can be reused and coin melted down, and the picture and motto of an emblem are similarly not permanent; emblems have, nevertheless, for a given time and place, a certain currency. Just as we do not pull value out of the air when we buy a pint of milk, but rather fish in our pockets and draw out coins of accepted worth; so when we speak and think we do not create meaning at will from the electrified puddle of our brains, but from the shuffling around of known units.

There was much debate in the cinquecento regarding the ontological status of emblems: were they simply metaphors, as Aristotle would have understood the term? Or did they approach the status of Platonic forms?

We now know the latter to be the case.

As the sixteenth century drew towards the seventeenth, emblems were not created so much as excavated, and Alciati came to be regarded as what he was not: an antiquarian.

An antiquarian approach to emblematising was not just a merit but a necessity because the emblematiser was increasingly seen as travelling back towards the font of (arcane, religious) knowledge; the explorer in these realms had to be equipped with a discriminatory understanding of ancient statuary, coins, medals and their reverses, intaglios, seals, inscriptions, classical texts, and so on. Individual emblems were refined, edited, brought closer, it was believed, to their Adamic and hieroglyphic sources.

And books of emblems came to be organised, not just as cabinets of curiosities (a word often associated with emblem books) but with taxonomical rigour, reflecting, in certain cases, the whole of the created universe. If emblems were a way of mapping the Platonic forms, a sort of mystical brass-rubbing, then any action coming to pass in the world of accidental reality would of necessity fall within some known region or other, would be closer to this or that emblem. It was, in the right hands a powerful, or at any rate, a persuasive science.

It is in this more developed sense of what an emblem and an emblem book is that I now understand Hunter Sidney’s observation. It is no simple matter to emblematise an emblem book.

NORBITON: IDEAL CITY is itself a loose-leaf book of emblems, a space in which and by which our various emblematic projects are organised, given their characteristic valency.

This is as much the function of a city as it is the function of NORBITON: IDEAL CITY. The accidental city, after all, is a jumble of emblems and imprese: institutions, for instance – lawcourts, churches, universities, barracks –each with its own emblematic accoutrements; suburban houses with nameplates and gates and gardens; electricity sub-stations emblazoned with signs; shops giddy with logos and slogans; billboards epigrammed with copy.

If the Ideal City is similarly a configuration of emblematic space, then its individual emblems are likely to inhabit the inter-emblematic space of the empirically real and accidental cities, insofar as the three intersect – they will tend to avoid, in other words, the gravitational pull of the emblems of the virtues and vices of the empirical city (success, passion, journey, creativity, negativity, what you will); and in order for this to be more than a temporary state of affairs, a futile ad hoc resistance, it is necessary to build a rival system of resistance – a structure of anti-emblems, if you will.

We are searching, in short, for an anti-emblem of emblems. No wonder Hunter Sidney is a little tense.

If I seem obscure (and I am not), then this is in part a function of existing too long in the superficially quirky emblem-space of the Ideal City, breathing a little too much of that radiant air.

The Emblems of the Ideal City are in fact quite simple – unlike those of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, they are neither cabalistic, arcane, invocatory, talismanic, nor magical.

They are, above all a sort of personal mnemonic and affirmation. A blazon of the personal, you might say.

For instance, Hunter Sidney’s mandrake root, I later come to understand, is derived from an incident in Mrs Isobel Easter’s garden, which took place many years since, and from which he dates his obsessive love for that woman.

And my own projected tattoo – for I also have requested a tattoo from Mandy and am, so to speak, in line – is a play on a complex of ideas which underpin one very personal aspect of my Ideal City.

This use of emblems to spark or affirm memory is not a peculiarity of Norbiton. According to Frances Yates, the emblem was always intended to function as part of a memory system. The image is a trigger: it springs the argument (the epigram) in your brain. To this end she quotes Aubrey’s life of Francis Bacon. Bacon, it seems, had emblematic images (“severall figures of beast, bird and flower”) placed in the painted glass windows lining the gallery of his house at Gorhambury; “perhaps his Lordship might use them as topiques for locall use”, speculates Aubrey.

Perhaps. The window, after all, is certainly a better place for an emblem than a book. Turning the page of a book is in itself emblematic, so to speak, of forgetfulness (unless that turning is underpinned by note-taking, and the note-taking by some sort of indexing, but then, who bothers with that?;[4]) if you wish to meditate on something, you need your object in plain view, hence my observation to Clarke about the placement of his tattoos. Although even then, placing the object of contemplation in plain view dulls the perception; after a while, we cease to notice it, it disappears (as the puddle-eyed old Chancellor of England might fretfully have noticed, pacing his galleries).

Perhaps it is more the case, then, that emblems in the Ideal City are as the tattoos on the flesh of South Sea Islanders, or the tattered much-consulted lists of obsessives, or freshly chiselled inscriptions on tombstones: they are a way, not of remembering, or memorialising, but of placating the memory. Write something down and you need no longer carry it in your head. It is out there, in the known world (even if it is only readable by the adept). You can forget it. Arrange your objects in such-and-such a way and they cease to have power over you.

Hunter Sidney wishes to know – this over his shoulder, Mandy already at work on his mandrake root – whether, time permitting, I will be having an emblem of the emblematic city itself, and I am unsure how to answer.

I have in mind a design as follows: a ship, modelled as far a possible on the ship in the pseudo-Bruegel’s[5] Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, in full sail, but retarded by a remora.

– LANDSCAPE WITH THE FALL OF ICARUS, AFTER PIETER BRUEGEL THE ELDER (?)

An expensive, delicate ship, Auden calls it. It is setting all sail for the immense dreamlike burnished paradisical beyond. But that ship, to my eyes, is in the grip of a remora. All that straining sail, and only the most trivial of bow wakes to show for it. It is going nowhere. It is a ship of poignant failure.

The course of my life, as with all lives – and, I would argue, all life itself – has been shaped by impedimenta, the things that on the face of it have held us back. I do not know that I am an expensive, delicate ship; or rather, I know very well that there never was any ship, nor any golden horizon – in the Bruegel that burnished sun is most likely a late addition.[6]

Whatever it was that emotionally, psychologically, practically, or accidentally held me back, was just the shape of everything that happened to be. The accidents of life are life, in other words. Learn to love your commensal remora, and set all sail just the same, sail at full throttle with the brakes on.

Mandy’s electric needle has now whirred into life. She is getting impatient, to be making her mark on the world. This is, in a sense, not Hunter Sidney’s thing, nor my thing, but Mandy’s thing.

Nonetheless, I hold up a hand, and over the sound of the needle make a suggestion: that both Hunter Sidney’s mandrake and my own remora-ship will be underwritten by a lemma or motto to accord with Clarke’s: Homo fuge! With the mental proviso that if we are all born to flee, then we flee, each in his or her own way, his or her own own demon.

And so Mandy settles to work.

Footnotes ☞

1 The Gombrich is from, Icones Symbolicae, I think. It is just possible that he did not read a lot of comic books. I should also point out that Alciati himself regarded his epigrams as in some sense Saturnalian. In 1522 he wrote to Francesco Calvo, a printer who was to arrange for the copying of the manuscript (rather than an actual printed edition) “During this Saturnalia I have composed a little book of epigrams, to which I have given the title Emblemata”. But I freely suppose that his emblems were designed to neutralise, not celebrate, the Saturnalia, in a private carnivalesque of the shrouded, the dry, the grave-dull. ⏎

2 Supply expletive.⏎

3 Hurry slowly. The Aldine impresa, first used in 1501, was a dolphin wrapped around an anchor. So Clarke’s denuded, dolphinless version renders down to Lente. Slowly. The Festina is all elsewhere, sporting in other seas. ⏎

4 I used to know students (in the days before everyone had a laptop) who carried boxes of index cards around with them. I would from time to time notice one of my peers flipping through a box of index cards in the library, say, and would idly wonder what they were up to; but, like an Aztec watching a Spaniard ramrod his gun, I failed to draw the correct conclusion.⏎

5 The painting was long believed to be by Bruegel, but is now thought to be a copy after Bruegel ⏎

6 One not cognisant, moreover, of the myth itself, unless Icarus has been taking a peculiarly lateral trajectory.⏎

Anatomy of Norbiton on HILOBROW

Original post at Anatomy of Norbiton: Emblematic

Anatomy of Norbiton

Short Life in a Strange World by Toby Ferris

Toby Ferris on Twitter

On the Paintings of Pieter Bruegel by Toby Ferris

All tapir illustrations by Anna Keen: portfolio