Norbiton (6)

By:

January 8, 2021

Anatomy of Norbiton: Architectural

‘The palace was primarily an extension of interior private space… Their formidable massiveness marks the limits of the civic world.’

Richard A. Goldthwaite, The Building of Renaissance Florence, 1980, p.16

– THE IDEAL CITY, VARIOUSLY ATTR., BALTIMORE

The Ideal City of the Renaissance—the città ideale—is a singularity in architectural space: a city of Total Architecture.

By contrast, architecture in the empirically real world appears only occasionally in the urban fabric. Undistinguished streets and squares give way briefly to an object that is something more, a super-dense concentration of built matter, a special case of building.

But the design of the città ideale swallows every element of the built environment into it. There is no building, no planning as such; only an infinite weight of architecture.

Notice, for example, how the people are tiny, bloodless, beyond recall: motes of dust disappearing over the architectural event horizon into some chilly stone-flagged Shangri-La of spatial experience.

When Lewis Mumford states (in, I think, The City in History (1961)) that there was never any such thing as the Renaissance city, only the medieval city tempered and punctuated by fragments—you might say scintillations—of classically ordered purity, he might have found the energy to add, as a footnote at least,[1] that those scintillations nevertheless altered the quality of built material (the functioning medieval city) in which they emerged; that the medieval city was also already endowed with architectural events and scintillations of its own (cathedrals, guildhalls, Bargello, Castello, etc.); that what now had come into being was a system of interactions and contradictions and mutations and malformations, which was in fact an empirically real city (I am thinking of Florence, Ferrara, Rimini and Rome, but there may be other examples); that, in short, the city, any city, had a history, was only typically renewed wholesale, like a forest, in the aftermath of fire, that otherwise it progressed by mutations, of which the Renaissance was one.

And had he been thorough enough to footnote his footnotes,[2] he could have added that the città ideale as variously depicted was a city without history, without time, hence, whatever else it might be, not a viable architectural system.

In NORBITON: IDEAL CITY there is no built material at all. Ours is not an architectural project but a city of soft matter, a slithery, unshelled mollusc of a place.

It may be that in time we will accrete built matter, however, like kidney stones or pearls, crystalline and uncomfortable menhirs of our progress; or we might metamorphose into a city of grottos, of quarried spaces, merely by repeated movement through our various interiors.

Or we might suddenly elicit a geometrical perfection as if from nowhere.

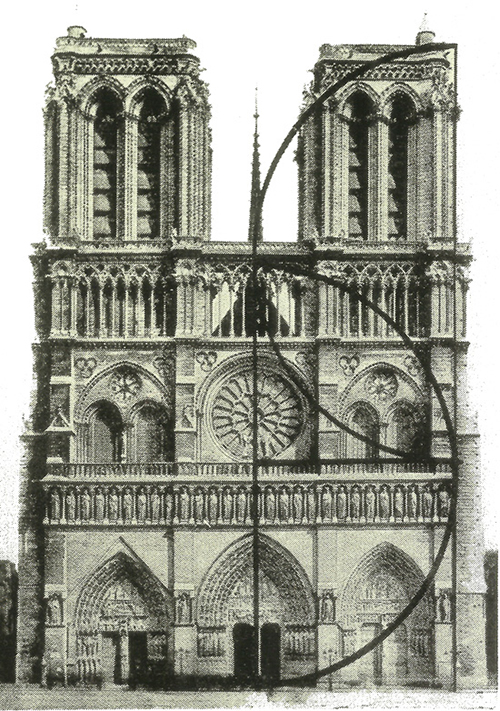

– NOTRE DAME DE PARIS, WITH ELEVATION GOVERNORS

LE CORBUSIER, VERS UNE ARCHITECTURE, 1923

But in the meantime, there is nothing. Just this infinite whiteness, like a blank sheet of draughtsman’s paper.

The cittá ideale was never meant to be built. It is a representation of the Platonic Ideal of city. All actual cities are to be understood as degraded and jarring and diseased approximations to this harmonic unity.

There are three painted representations of the cittá ideale from the quattrocento which are usually considered as a group. They now hang in Urbino, Baltimore, and Berlin, in accordance, not with a resonant logic of place, I suppose, but the geographical logic of money.

They have been variously ascribed to the authorship of Luciano Laurana, Piero della Francesca, Leon Battista Alberti, Fra Carnivale, and others, but their generic anonymity is appropriate. The city of total architecture requires no architect. The architectural pressure is equal in all directions; or, put differently, the organisation of the space does not constrain or coerce so much as etiolate the citizen.

The implication is that architecture—the architect—bends space, and this is clearly true. An architectural object is a gravitational mass in the city. As the ribs and knuckles and sockets of the skeleton of the body, when laced together with tendons and ligaments, provide a coherent and flexible structure which lend not just mobility but balance and poise and sometimes even grace to the flesh; so the walls and pavements and arcades and roofs of the city parcel up space, separate out interior and exterior, regulate the flow of light, air, and human beings.

The architect knows this. Architects make buildings which are conceived in terms of flow and movement, for all that they are static entities. Buildings have a hydraulic quality to them, so many sluices and locks and dams regulating the flood that will purify the city.

All architects are, in the end, spatial hygienists, impatient of the squats and shanty towns and cardboard cities of the mind.

You cannot know a city, architecturally.

Architecture, as I have said, is unevenly distributed through the fabric of a city. It pops up here and there in the form of a church, a stadium, a railway station; or as a house among houses, a palazzo among palazzi, an office block among office blocks. The architectural connections around the city are confused, stratified, arcane; there are epochs, styles, imitations, echoes; the centres of gravity have shifted and uplifted and submerged and metamorphosed over the millennia, nothing is where it should be, nothing is complete.

You require a guide, a priest of the arcane, a Baedeker or a Pevsner. Or you require a vast architectural anchor—a cathedral, say—around which the city is seen to be organised, and to which every element of the city relates and submits.

But a cathedral is, like the city it dominates, a pile of fragments, historically distended—conspicuous enough from a distance, hard to read close to.

And so even here, with your Pevsner and your cathedral, you gawp and fumble like Parsifal at Monsalvat, attempting to distinguish pier from pilaster, corbel from moulding, decorated from perpendicular; trying and failing to trace the lines of force. And however comprehensively you cover your building or city of choice, there will always be some angle you miss, some detail of experience.

– BIT OF YORK MINSTER

Because the cathedral, like the city, while informed perhaps by simple and generalisable rules, is not exhausted by them, still less made of them; but is, rather, and to repeat, a sedimentation of lost civilisations and cultures, of dead masons and labourers and citizens, of the eternal recalcitrance of materials and the scarcity of resource and the exigencies of the moment; a mosaic, in other words, scattered from the minds of men over the face of the earth, jumbled thereupon and lost; a shattered mosaic not of an ideal city but of a half-formed impulse tending to the ideal – the impulse to build well, let us call it, although it is more complex than that; an impulse in any case which we now we seek to reconstitute, on foot, stone by stone, Baedeker in hand, hopelessly outnumbered.

Empirically Real Norbiton is a city of modest but not inconsequential architectural heritage. There is the Lovekyn Chapel for one thing, and the cité radieuse of the Cambridge Estate.

– NORBITON: VIEW OF THE CAMBRIDGE ESTATE

And then there is the story (for the building no longer exists) of Norbiton Football Club’s extraordinary moment of architectural apotheosis: the famous Palladian North End, thrown up in a whirlwind of energy by Ted Kelley at the end of the 1980s, and as rapidly demolished.

– NORBITON: KINGSMEADOW FOOTBALL GROUND

Norbiton F.C. emerged as a hospital team in the 1930s, and spent the next fifty years in bitter, almost exclusive competition with its larger neighbour, Kingstonian. For a spell in the late 1960s it punched above its weight in the Isthmian league while the Kingstonian, presumably, were slumming it; but a history emerged of giant-killing Norbiton and unscrupulous Kingstonian poaching their best players. It was a history of very local loyalties and betrayals.

There was one blissful window, perhaps only a couple of weeks long but eternal like a childhood summer in some minds, when the Norbiton had seemed poised for promotion and Kingstonian for demotion; but Kingstonian had snatched a late draw at the Rec. one spring evening, a goal from nowhere, a fluke, a gift of (a vengeful) god, a goal scuffed and diverted off the shank of a Polish journeyman centre-half, previously of Norbiton F.C., one of the traitors then who managed only half a season for his new outfit, comprehending nothing anyone said to him or anything happening around him except this deaf-mute’s ballet on the muddy turf, and, by all accounts, not too much of that either; who not long after disappeared for ever into some parallel rack of stories; and yet who nevertheless blazed an unknowing destructive comet trail through the lives of hundreds of strong men; in short, Kingstonian stayed up and Norbiton stayed down.

The dog-fight continued for a season or two, but by the end of the decade Kingstonian were on an upward trajectory and by the early 1970s, with the Isthmian league starting to admit professionals, the Norbiton were a faded force. They slipped rapidly down the new divisional structure, and met Kingstonian once or twice again in cup competitions over the next twenty years, before, (following one last fluorescence) they were swallowed forever by their powerful rivals. For a few years the team was known as Kingstonian and Norbitons, but that didn’t last. Norbiton F.C disappeared, like some Etruscan city of legend, only the ageing haruspices in a corner of the North End retaining a memory of what they had once been, the terror of the league, defender of the little teams, tyro of South London.

The Palladian North End, so called in pride and resignation by a dwindling core of supporters, was in fact nothing of the sort. Palladian, that is. How the structure came to lay the Pazzi Chapel of Brunelleschi in Florence quite so heavily under tribute I can only conjecture, but, if Clarke’s memory is sound, the stand was Brunelleschi to the rafters: unfluted column shafts, eight-volute Corinthianesque capitals, spandrels in the roundels (showing reliefs of sporting endeavour), groin-vaulted loggia. Brunelleschi died over sixty years before Palladio was born. The stand was Brunelleschian, not Palladian.

– PAZZI CHAPEL, SANTA CROCE, BRUNELLESCHI

Also, it was not the North End that was, as we have now agreed, Brunelleschian; not the whole of it at any rate. It was the directors’ box. The little Pazzi Chapel construction sat in the middle of a low slope-roofed concrete terrace such as you might have seen in any crap ground of the country in the 1980s (and that was most of them). Only, between the flat roof and the pillars supporting it was some layering, some untutored moulding suggestive of entablature, and the roof ranged with the springing of the central arch of the chapel/directors’ box, above the entablature of its triple-time columniation; there was even, at the summit of the rough concrete piers supporting the roof a little hint of a fuckwitted capital, the Norbic order if you like.

The order of the directors’ box, in other words, controlled the whole stand, made it intimate, coherent and, in the eyes of the opposition supporters who would gather (if they bothered coming) in a windy corner of the East Stand, perplexing; their songs floated out like seaman’s dirges, Odysseus’s homesick crew at their oars, having a mirage vision of home and its civilities, some intimation of calm and dignity, of rational virtue, in the midst of the flagging muddy bronze-age suffering of their team on the pitch. As Clarke recalled for me, the twelfth man for us that season wasn’t the crowd, it was the fucking Pazzi Chapel and the birth of the Florentine Renaissance.

The story goes around now that Kelley wanted to make the football stand one of the nodes of an underground or hidden city. This is one version of why the breeze block Pazzi Chapel suddenly appeared in Norbiton.

His secret plan, so the legend has it, was to connect his house, his garden, the football stadium, and perhaps some other key places, by means of covert tunnels and disguised bridges; Norbiton was to be like a Vatican labyrinth, and the Pope, as it were, or the Minotaur, was to be his wife, the agoraphobe. It was to be a way of getting her out of the house, walking in silence along twisting routes between public places. She would be able to participate without interacting.

According to this reading, there is an arcane connection between the Palladian North End and Kelley’s other activities in Norbiton and environs—and some are including the IDEAL CITY and the Anatomy in that list, I understand.

Whether this was Kelley’s compromise of an ideal city, or whether it was a way of satisfying still further his need to control, to treat his wife like a harem of one, the legend does not really say. However, whatever other objections can be laid against it, it simply does not fit with the chronology as I understand it. Kelley’s wife took to her isolation after the stand was demolished.

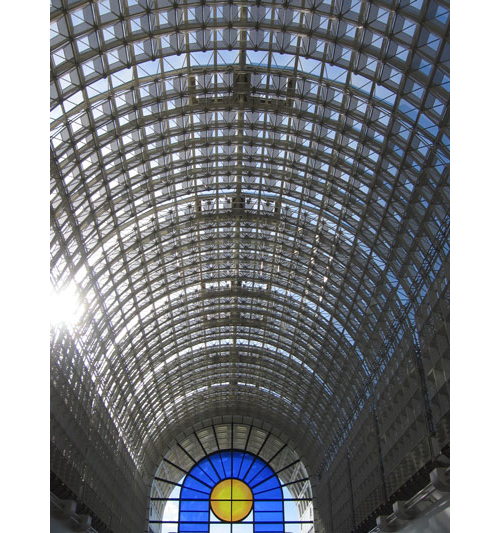

If there was an arcane connection with other architecture, it was undoubtedly with the Bentall Centre, just then gaping into life across town in Kingston.

– THE ORIGINAL UPLOADER OF THE IMAGE WAS SUE WALLACE AT ENGLISH WIKIPEDIA

(TRANSFERRED FROM EN.WIKIPEDIA TO COMMONS.) [CC BY-SA 2.0

(HTTP://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY-SA/2.0)], VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The Bentall Centre was part of a redevelopment of central Kingston between 1987 and 1992, masterminded, not by the imbecile and enfeebled Bentall dynasty, but by a collection of financial instruments and entities centered around the machinations of an ex-patriot Italian who had made his fortune in the building trade, Tony dell’Aquila. It was Tony who put together the various consortiums, drove plans through the council, and slowly, powerfully, secured his own vision of a retail behemoth for the 1990s.

And it was Tony, doubtless, who selected the firm of architects responsible for the redevelopment (for the Bentall Centre was manifestly the product of a firm, not of an architect) and approved the final design.

The new mall retained the original facade, telephoned in by Maurice Everett Webb in 1935; a pleasant and entirely nondescript selection of classical-style detail—pediments, vestigial pilasters picked out in brick, a pair of urns—gathered around, rather than organised by, a squished tetrastyle portico.

The twinned figures surrounding the windows of the curved front, and the shield between them, were sculpted by a marauding Eric Gill, who with characteristically insane perspicacity understood that what this feeble classicized building most needed was four bewildered gothic stone-nymphs clinging to the exterior.

But Gill’s was a futile gesture, especially in light of the new development of late 80s, which was grafted to the bleeding stump of the old Maurice Webb building like a deranged capitalist prosthesis. It was as though a whole firm of coked-up architects was now also mainlining beautiful pure white classicism just for the giddy unrestrained rationality of it. How else would you produce such a crystal white spurt of cosmic jism, a space so ecstatic that if you weren’t shopping in it you’d be dancing yourself to death in a disco trance?

– THE ORIGINAL UPLOADER OF THE IMAGE WAS SUE WALLACE AT ENGLISH WIKIPEDIA

(TRANSFERRED FROM EN.WIKIPEDIA TO COMMONS.) [CC BY-SA 2.0

(HTTP://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY-SA/2.0)], VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

What whiteness, you ask yourself, will you add to this whiteness? Kelley’s Palladian North End was by comparison a necessarily crappy counterpoise, its wonky breeze blocks starting to look like a form of sanity, heaved into place as they were not by orgasming angels, but by a sweating Irishman.

It was Tony dell’Aquila, incidentally, who bought Kelley out of Norbiton FC, and demolished the Palladian North End.

In the same way that we do not really know what Kelley’s plans for the Palladian North End were, we do not know the architect of this (retrograde) visionary stand. We know that Kelley built it, almost single-handedly. We do not know who conceived it, designed it.

Kelley himself? It used to be generally believed so, but Clarke reports that Kelley once told him that when some of the finance for the stand backed out and the builders were withdrawn, he decided to continue by himself if need be; and when on the first evening he went over there to establish how things stood, he was left scratching his head with the blueprints and the piles of rubble, and he didn’t even know which way up to hold the blueprints. He wasn’t really even a builder, even though he had worked on plenty of building sites in his youth. He managed a stone mason’s business. And suddenly he was chewing on the bones of a major project.

So if there were blueprints, who drew them up? The plain fact is, I do not know. It is not impossible that it emerged, as cathedrals emerged, from a practice, the complex interaction of craftsmen under the benign oversight of one master builder—Kelley.

I like the idea that Kelley, not an educated man, discovered the stile nuovo all over again in a corner of South West London, as though a Tuscan take on classical architecture were a particularly powerful attractor in architectural space.

Emmet Lloyd is on the board of Kingstonian along with Kelley (and the terrifying Tony dell’Aquila), even though Emmet knows less about football than I do.

Thus it was that, when we talked about the Palladian North End one evening in the Norbiton and Dragon, Emmet, like some callow revolutionary, proposed wresting power from the board and building the stand again. As with his Dendronautilus (for a reminder of which, see Arboreal, here), his instinct was to aggrandise (or to please us, one or the other), and needless to say we paid no attention to the idea. But the suggestion did spark in us a small architectural ambition, which was to build a scale model of the original stand.

I was excited by this, partly because of the model (I envisaged myself towering over it), but mostly because before we could build a model we would need documentation – plans, elevations, blueprints. We would have to assemble eye-witness accounts and sketches, hunt out old photographs, build a project dossier which we could hold in our library and handle only with white gloves.

The documentation, in fact, more or less marked the limits of my ambition, which was to be, like those of so many architectural fantasists who could never hope to see even a solitary percent of their (greatest, most ambitious) designs realised in stone or in space, a paper architect: a da Vinci, or a Boullée, or, well, take your pick. Most architects when it comes down to it, or perhaps all architects most of the time, are paper architects, working in the realm of sketches, doodles, cardboard models. Paper, with its imperative to think in images, is architecture’s proper and native realm.

Paper is the currency of architecture, its medium of exchange. Plans, blueprints, legal contracts, planning regulations, specifications; all of these are satisfied or fed by paper. The building passes into and out of two dimensions on paper, at various stages. Architects struggle to convert their visions of three-dimensional space into two dimensions, and builders counter-struggle to reconstitute a three-dimensional object by interpreting the various elevations and specifications available to them.

Architecture which remains confined to paper, therefore, occupies a sort of ideal space. The laws of physics, the nature of materials, and the exigencies of commerce make no demands upon it. It is not, properly speaking, architecture; but then neither is it mere building.

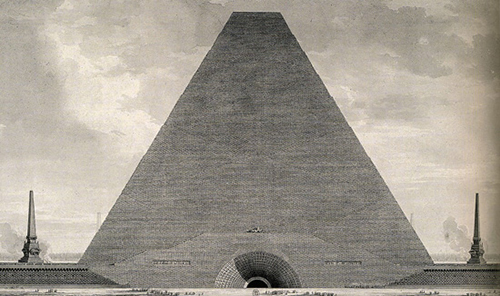

Étienne-Louis Boullée (1728-1799), were he alive, would be Architect-in-Chief, or perhaps Paper Architect-in-Residence, of NORBITON: IDEAL CITY, not because we like his buildings but because he failed ever to have his most important constructed. His Architecture: essai sur l’art, containing his greatest designs, was, with supreme insouciance, first published in 1953. His spent the best of himself in a hugely productive limbo of disegno, and it is no surprise to us that he was both celebrated in his lifetime and influential after it.

His conical cenotaph merits consideration as our first—and only—architectural project, mostly because were it to be built it would crush ALL OF NORBITON beneath it.

– CONICAL CENOTAPH – ÉTIENNE-LOUIS BOULLÉE

There is an entrance there, an invitation to a quiet, cool, most likely spacious and I like to think marbled subterranean world. This might after all be a cenotaph to a living people, a termite race, a pink-eyed priestly caste; an object of wonder to the commonwealth of nations—or at any rate to the inhabitants of Kingston or Wimbledon, for whom our construction would unfortunately blot out the sun. See for example how, in this illustration, they are foregathered in order to marvel at the apocalyptic scale of our hubris!

We began by noticing that the città ideale was an architectural singularity, a civic object of total architecture.

Strictly speaking, however, it was nothing of the sort, in part because it was only a representation in paint, millimetres thick, light as dust; but in part also because it represents a city where the exteriors – the piazzas and streets – are all interiors, a great sunlit and circumbound inside. It is a city turned inside out.

You never truly venture outside in a city, never mind that you can see the sky. Outside is just another room, a continuum of interior spaces. The only outside is beyond the city.

However, this continuum or gradient of interiors is experientially differentiated, and the città ideale removes one end of that gradient.

NORBITON: IDEAL CITY, by contrast, is in its weightless papery way the quintessence of a city of graded interiors. What are the rooms we inhabit, after all, but volumes and spaces? What is our furniture if not a series of masses? Books are ornamentation, knick knacks decorative elements, the route to the door from our desk a thoroughfare, the stoop to the printer under the desk a back alley.

We are continually operating on this interior space. We make small home improvements, rearrange the furniture, dig ponds in our gardens. And in time these tidal alterations, these transformations and adaptations, will take on a direction, a longshore drift. Thus, to take an example, a terrace of houses is not a uniformity. It is a shanty town of inventiveness, resource, expedience. The backs of terraces in particular are an endless mutation of sheds, cold frames, extensions and loft extensions, external stairways, doubled gardens, fences, walls, hedges; a seamless variegation in patched stone, paintwork, tiling. Given time it will take a practiced eye to pick out the commonalities.

– FAIRMOUNT NEIGHBORHOOD OF PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA FROM THE 11TH FLOOR DECK OF 2601 PENNSYLVANIA AVE, OVERLOOKING 26TH AND ASPEN STREETS INTERSECTION, LOOKING NORTHEAST

Architecture is nothing more than taking control of this universal mutability; it starts, not with thinking—thinking is a corrective to work already under way, a largely retrospective activity—but with some deliberative action: a walk taken, an object moved, a sketch made.

In NORBITON: IDEAL CITY we have no built environment, no stone palaces or steel skyscraper. What we do have is an immense and variegated and articulated interior—one upon which we operate deliberately.

Footnotes ☞

1 perhaps he did; I haven’t read the book

2 Again, for all I know the man was an inveterate footnoter of footnotes. But the point stands.

Anatomy of Norbiton on HILOBROW

Original post at Anatomy of Norbiton: Architectural

Anatomy of Norbiton

Short Life in a Strange World by Toby Ferris

Toby Ferris on Twitter

On the Paintings of Pieter Bruegel by Toby Ferris

All tapir illustrations by Anna Keen: portfolio