OFF-TOPIC (21)

By:

August 18, 2020

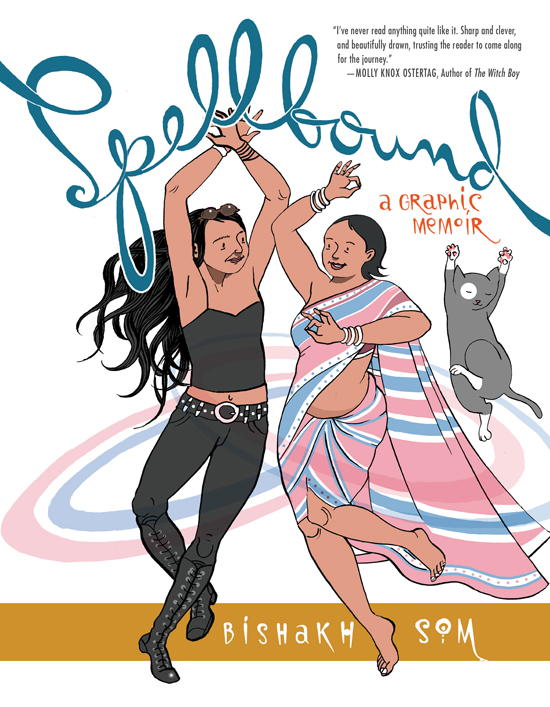

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This time, a revisitation with one of haute comics’ most already-immortal talents, on the occasion of her second life’s story in the space of one year…

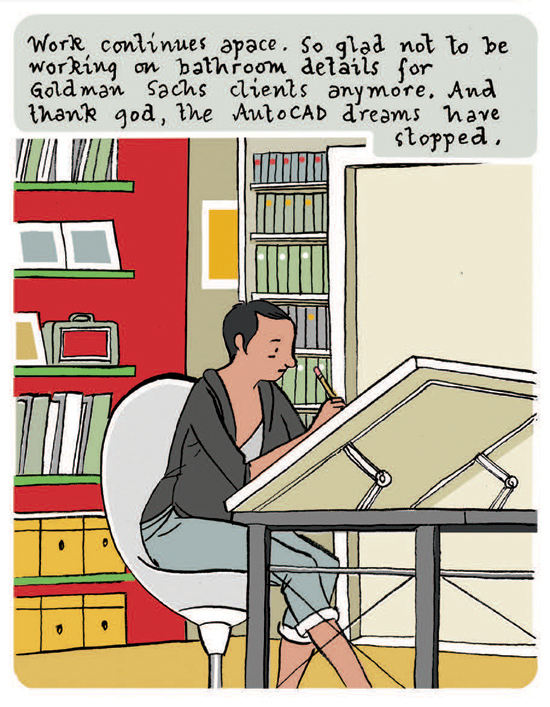

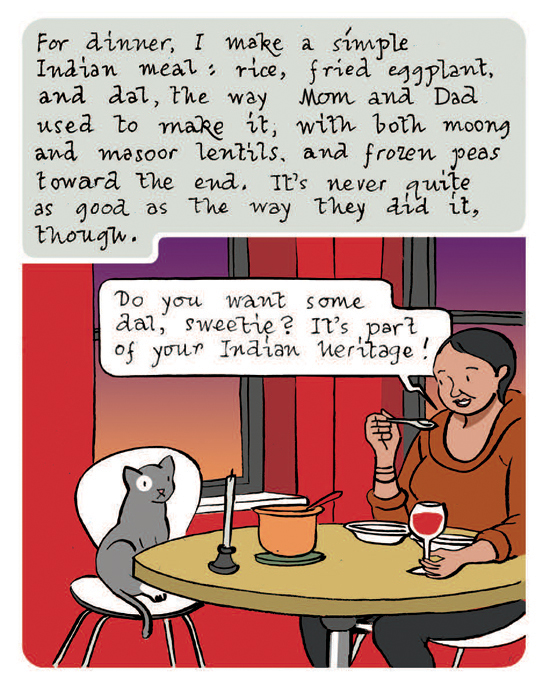

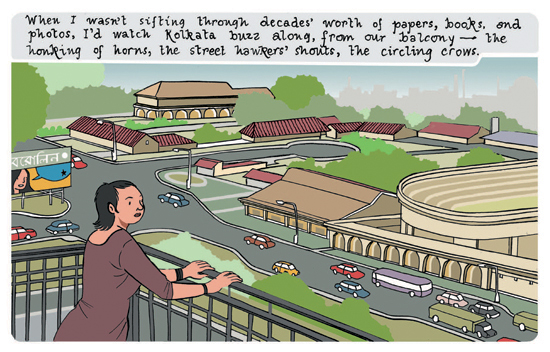

You can’t really travel to a parallel reality, but you can break out of someone else’s. Cartoonist Bishakh Som had been existing once-removed in her ongoing web comicstrip Anjali & Ampersand, an outlet in more ways than one that Som started as a kind of graphic journal that filled the time while her more grand-scale work Apsara Engine was on its long path to publication. Starring a young creative and her cat, the strip was a shadow-life into which Som projected the anxieties of her leap from a prestigious architecture position to an uncertain illustration career, her ease in any setting and out-of-placeness in all of them as the widely-traveled child of two UN employees who is now living in the bubble of Brooklyn, and the trauma of caring for parents who died early, a hemisphere away.

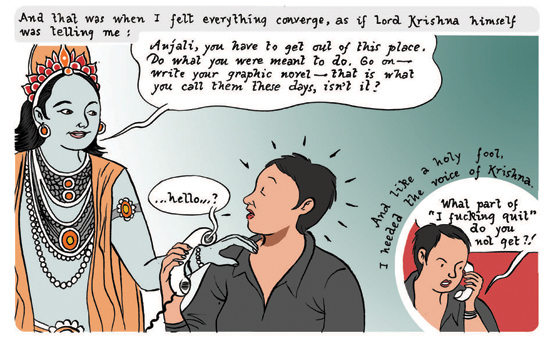

A kind of offset autobiography, but miraculously, one with an eventual end that Som is still here to tell: over the course of Anjali & Ampersand’s episodes, Som reached the realization that she is a trans woman, so in a sense the at-the-time gender-reversed protagonist came back home to her creator. Now Apsara Engine is an acclaimed, published milestone, and in the same year Spellbound arrives (on August 25), as a complete memoir filling out Anjali & Ampersand to what it always was meant to be. Som herself now appears in the narrative, giving context in a kind of curtain-speech recounting the years of her life that led up to the beginning of Anjali’s on-paper existence, and returning when all of us are up to date.

In-between, the comedy and tragedy of creative drive and doubt, class self-consciousness, cultural convergence and collision, unsparingly recalled and illuminatingly perceived loss, fumbling eros and scene-stealing cat-cuteness played out by Anjali, Ampersand, and her family, colleagues, lovers and nemeses coalesces into a lifetime seen from the outside but felt with phenomenal intimacy. This kind of story could suffer from being self-referential, but Som makes it an encyclopedia of identity in which everyone has a point of familiarity from which to recognize and learn. Anjali takes on a life of her own, and her author has sketched out the map to hers as well.

We spoke, out-of-body as quarantine demands but in-character as always, to talk over mirror-images that don’t match, the recipes for one’s truest life, and how all the world’s a stage of grief…

HILOBROW: It’s fascinating to see how the paths between your life and Anjali’s story converge and diverge. That’s an effect that’s always intrigued me, in cases like when writers leave a fictionalized play and a written autobiography for us to compare, and pick out which incidents happened and which were fabricated. I’m hard pressed to think of a case where a single narrative goes in and out of register like that, other than Spellbound. It doesn’t feel just like a pairing of Bishakh’s and Anjali’s existence side-by-side, but almost like a series of crossroads at the quantum level, where you can see different ways either of you could have gone. Is all storytelling a kind of navigation of those cosmic maybes, or do you just prefer to dwell, or at least travel, in possibility?

SOM: I guess it depends on how deliberate I thought I was being with dipping in and out of the Anjali narrative, in terms of its veracity. But also I kind of didn’t care? I didn’t intend for there to be such a divide between my story and her story. I don’t think I was interested for the reader to untangle that. Some people have called the book a sort of puzzle, but that’s not what I intended originally; the point of the book wasn’t initially for the reader to suss out what my story was and what Anjali’s story was and how much of it was true and how much of it was fantasy; to me it was just a sort of natural dance between the two of us. I didn’t see that as part of the initial strategy of the book; it becomes a sort of exercise in ticking boxes.

But I am interested in the idea that storytelling is like that, it’s like a constellation of possibilities, some of which are drawn from real-life experience and some of which are embellishments or fantasy or whatever. I like the idea that storytelling can be a hybrid of those two modes. Once I was certain this was going to become a book I wrote new episodes to fill in some gaps in the story, but then there were new episodes that were more like flights of fancy. Like the Titania character; [she’s] a way of addressing the whole issue of reckoning with your gender, because Anjali is a cisgender girl, I’m not, so, I was trying to figure out how to address, how to introduce my own coming to terms with my gender into her narrative. That’s when the trans character comes in, and they form a relationship, which is kind of like the way I form a relationship with my own realization.

HILOBROW: It’s funny how both of your books have arrived at a time when we have to reassess… maybe everything, but there’s some very specific things about this book in the context of a quarantined era. Of course you couldn’t have had that in mind, but, refreshingly, though Anjali gets as stir-crazy as anyone, there is a lot here about the joys to be found in solitude as well — a kind of monastic discipline, a centering assessment of your life and self. For the more private disciplines like art and writing (as opposed to the more collaborative ones like music and theatre), it’s always been a question of how much do you like to be alone and how much should you be out in life. What is that equation for you?

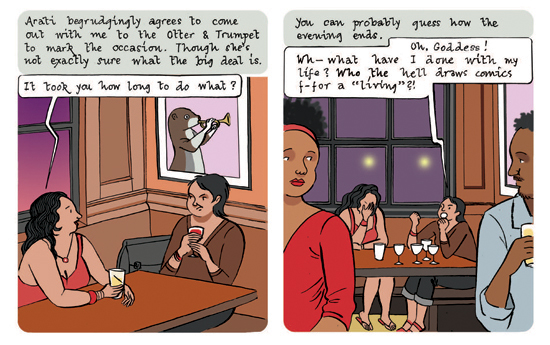

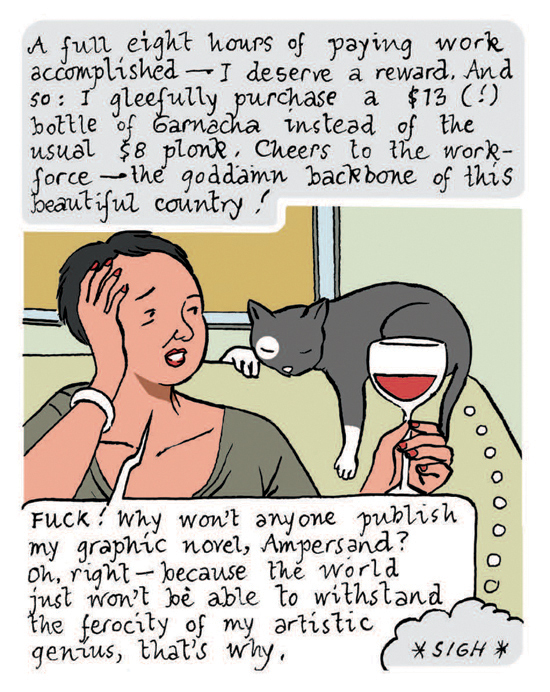

SOM: It boils down to how she’s able, and I was able, to have the good fortune to work from home, at a time when… I guess the thing that kept me going was the idea that — and Anjali does this quite often — which is that she rewards herself, usually with a bottle of plonk [laughs] at the end of the day, and I had my rewards too, whether it was meeting [Som’s wife] Joan after work or whatever, and those little nuggets of promise made it worthwhile for me to get through the day, working on comics and art. So as much as the book is a meditation on how you have to live your life if you want to pursue something like a book — which is to hole yourself up in your studio and just produce the damn thing — which requires hours and hours of being alone, I never thought that it would end up becoming a sort of mixed model of how things are now. I was done with the book when this all started. This isn’t the book to answer any of those questions, other than reflect on what one can do given a certain amount of isolation, which is, y’know, make art. Which is actually what I’m doing now, going back to the small paintings that I used to do before Spellbound; I was just kind of working things out without overthinking it; just working out visual ideas. Now I’m back to that again, after two books where I was very deliberate about how to make art. And thank goodness I have this; going back to it has been a very vital coping mechanism.

HILOBROW: You mentioned the rhythm of Anjali rewarding herself, and not just with booze; food plays such a huge role in Anjali’s story. Even before I came to the back of the book where there’s an actual recipe, it got me thinking of story as a kind of recipe — where, as we were saying before, different ingredients can have widely different outcomes. It’s obviously an important anchor for Anjali, not just as a marker of the day’s work done but as a cultural reference in her memories of her folks and as she says, “nostalgia for a past that never existed.” I realized that even the styling of the chapter-headings made me think of the tabs in a file of recipe cards. [Laughter] What importance and meaning does food play for you personally, as itself or as a metaphor?

SOM: Initially I started going into detail about what she’s cooking because, when I quit my job and I was embarking on this year-plus of devoting myself to making art, I imposed austerity measures on myself. There was no more going out to buy lunch as I did when I was working at an office. So for the first time in my life I guess, I was making food for the whole day, lunch and dinner (other than when Joan and I cook), and I started to think about ingredients in a very specific way, because there was no way I could be extravagant about it. So I had to cut back on things and be deliberate about what to use and how much of it to use. So that became part of my thinking when I entered that phase of my life; and it naturally became part of Anjali’s thinking. That’s why there’s all this talk about the parts of vegetables that one would normally throw away that Anjali has to incorporate into her meals [laughs].

Then it became a little more than that; it would tie back to culture, and to things that tie me back to my parents. She goes on about this a little bit in a couple of episodes, where she’s bemoaning that everyone is so focused on food, even though she’s doing the same thing talking so much about what she’s cooking for lunch and dinner. It becomes obvious to the reader that she’s unable to escape that cultural cycle that has bred her. That’s true for me too; I’ve gotten frustrated by how much people used food as a substitute for talking about other things that were more important in my family. But then I always went back to talking about food, because I enjoy talking about food, maybe even more than eating it. It was a way to highlight that conundrum.

HILOBROW: Those incidental details are what make the bigger picture feel so real… one moment of sharp observation I love is when Anjali has a possible love-interest over for dinner and suddenly Ampersand stands up at the table to greet her guest — it’s moments of emotional recall like that that astonish me the most in narrative construction, because it’s like, the things that you notice at the time but forget two seconds later; it’s amazing how that stuff stays in… does that come spontaneously when you’re forming a story, or do you save it up for future use?

SOM: I think so, but also, I was trying to, I thought of Ampersand as a Greek chorus in a way, so he’s amplifying thoughts that are already sort of in the ether while the comic is going on, he’s energizing them and making them more explicit in a way.

HILOBROW: So he’s showing Anjali how much she likes Titania.

SOM: Exactly.

HILOBROW: There’s two kinds of ghosts in this story, so to speak; echoes of the past, and heralds of the future. Spirits of a life Anjali used to have, and harbingers of who she’s becoming. Some symbolic, and some maybe literal — though the reader will have to find that out for themselves — but each, in time, a form of peace and comfort. We’ve both had early-in-life scares and losses, and can maybe testify to when the clouds clear. Have you reached a point where some of those shadows have fallen away for you? Or, is that in any way something you wanted to portray (whether or not you’re feeling it) in this book?

SOM: The trauma I felt and that Anjali feels was most directly portrayed in the one chapter when she has to move her parents back to India. And writing that episode was a way for me to work those issues out too. Because I felt like I never went through a grieving process, ’cause I felt slightly incapable of it? Doing the comic was both a sort of testimonial, and a way to say, well maybe this is how I can grieve. Those “five stages” never happened with me, that’s why I find it interesting, because I don’t know how much that’s true for people, generally.

HILOBROW: I think the only thing that really is “universal,” if anything, is our tendency to measure ourselves against various expectations, including those five stages. More people than not, I find, talk about, “Why am I not feeling what I’m supposed to be feeling?” We don’t grieve on-schedule… especially when you’re caring for people, you consciously shut down certain parts of your emotions —

SOM: You have to.

HILOBROW: — and switching that back on is not so easy… if you ever even want to.

SOM: I guess not, but it makes me feel weird, like, what’s wrong with me, y’know, where’s my emotion-chip? It got lost in the post or something!

HILOBROW: Well I can assure you that nothing’s missing, and you bestow such great feeling in books like this.

SOM: As for, like… I’m not going to psychoanalyze myself to see if the veil has dropped for me or not yet, because it still kind of reappears and disappears, so I don’t know. But I think that’s as far as I was willing to go in the book, with trauma. It would take another kind of book to address the real depth of what I, or Anjali, might have really felt, and it might have turned into… it wouldn’t have been in this book, because then it would have been, like, this black abyss in the middle of a fairly sweet and charming meta-memoir, but then there would have been a gaping, kind of, like, Lovecraftian part [laughs], which would have made the whole thing very jarring. And I don’t even know if I’m capable of writing that memoir yet, or wanting to process that way.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE