Cross-post (20)

By:

July 9, 2020

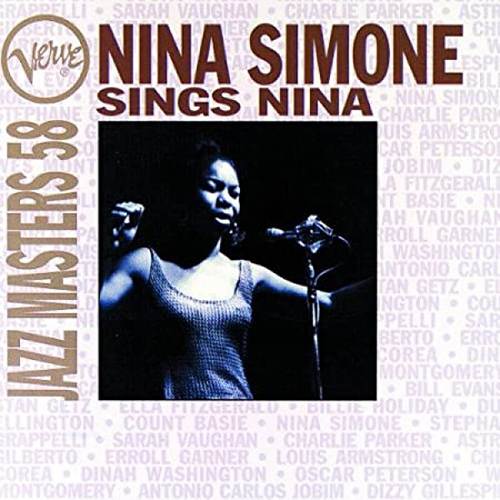

Nina Sings Nina

My liner notes to the 1996 compilation album

In 1995 or 1996, when I was an editor at Pulse!, the magazine published by Tower Records, I was the last person in the office one day when the phone happened to ring. It was an editor at the esteemed Verve record label, looking for contact information for one of our frequent contributors. We got to talking and I mentioned my affection for Nina Simone, whose music I was fairly addicted to at the time. He said that the recent compilation in the Verve Jazz Masters series had been such a success that perhaps I should propose a sequel. I proposed two, one of which was the CD I would proceed to sequence and write liner notes for. (The other, which was not picked up, proposed Simone tracks that I felt were optimal for hip-hop producers to sample.)

The album Verve Jazz Masters 58: Nina Simone Sings Nina was released in 1996. I spent an enormous amount of time on it, and remember having to use a cassette deck to tape and then test out various potential sequences of the songs. My liner notes to the album used, I believe, to be on Disquiet.com, but at some point, during one or another transition, disappeared, so I’m finally today, at the end of a long week almost halfway through what will continue to be a very long and arduous year, posting them here.

On the best-loved version of the most famous song she has ever composed, “Mississippi Goddam,” Nina Simone tells her Carnegie Hall audience between verses, “This is a show tune, but the show hasn’t been written for it yet.” She is only half joking. Simone’s writing, for all its majesty, has always seemed incomplete. Rather, her original songs suggest themselves as scraps of something larger, perhaps several things larger — a show, indeed, but also an autobiography, a treatise of gender, a political manifesto.

[This is a different, but still great! version than the Verve track Marc mentions above. — PN]

Perhaps “scraps” is not the best word. Simone’s original songs leave no seams showing, no couplets to be rhymed, no bridges to be built. “Synecdoche” better describes her compositions, meaning the part that signifies the whole, like a fin for a shark or a top-ten single for a career. But such a scholastic term would surely scare off novice fans tickled by her cover of “My Baby Just Cares for Me,” a recording who’s recent appropriation by film and advertising testifies to Simone’s continued appeal.

Yet how else to describe the sense of greater context that halos all of Simone’s songwriting? Isn’t “Four Women,” with it’s innovative modulation between characters, more dramatic than most full-length musical shows? Aren’t her anthems, “Mississippi Goddam” and “Old Jim Crow,” purposely tough acts to follow, their rousing choruses meant to dispatch the audience into the streets? Simone writes each composition as if it were the one she wants on her tombstone. “Sugar in My Bowl” is suggestion, seduction, and recuperation wrapped into one pop song.

Live, May 6, 1988 in Hamburg – Fabrik

Simone’s songwriting is most remarkable for its breadth. She has constructed identities from the music and words of others, as did the generation of jazz vocalists preceding her, but she has also created varied personae in songs she has written, anticipating the autobiographical endeavors of rock’s singer-songwriters. Her concert programs are patchworks sewn from gospel and folk, Broadway and blues. A Simone performance is as likely to be written by her as it is to be written by someone else: She composes in every genre, as if the music business were some artistic decathlon and her songs must compete in each event.

The tunes heard here include gospel (“If You Pray Right (Heaven Belongs to You)”) and pop (“Sugar in my Bowl”). Her political work ranges across the folk music tradition; it can be as comic as Tom Paxton’s (“Go Limp”) or as resolute as Woody Guthrie’s (“Mississippi Goddam”). She adapts texts widely, using the lyrics of a contemporary of Byron, Thomas Moore (“The Last Rose of Summer”), and a figure of Harlem renaissance, Waring Cuney (“Images”).

And no matter what its context, each song carries the scent of autobiography. Her lyrics clearly relate to her public life: to matters of racial tension, social issues, and sexual politics. Furthermore her songs illuminate her musical autobiography, the snatches of Bach and gospel from her childhood, the echo of popular standards of her era, the folk-song agitprop of the civil rights movement.

She is famous for coming to composition by circumstance. As a single young woman supporting herself playing piano, she improvised — for self-preservation, not out of a deep understanding of jazz — to fill out arduous cocktail hours. As the civil rights movement drew her in, she found subject and audience for her unique voice. The alto that tunneled through “I Loves You, Porgy” and the keened Ellingtonia had something of its own to say.

From the album “Little girl blue” (1958)

But songwriting has never been the primary focus of Simone’s career, given her talents as a pianist, arranger and, of course, a singer of other composers’ songs. Her own songs generally remain uncovered, though few among the new generation of women in rock and soul haven’t claimed her influence. This must be painful for a woman who has treated the songs of others with such engagement.

In retrospect, Simone’s considerable catalog — in her autobiography more than 40 albums are listed, omitting gray-market titles — effects a false impression of her appreciation of her songwriting. It might seem that she thinks it is secondary to her work interpreting other’s songs: No release on the Philips label, the core of Verve’s Simone holdings, features more than three Simone originals. Many of the Philips-era originals were drawn from the concert she gave in the spring of 1964 in New York City, spread over a handful of albums. The implication is clear: Live, Simone called the tunes, her own well represented on the program. But the record companies chose not to focus on her compositions. It wouldn’t be the only disservice to her done by the music industry.

Verve’s catalog does not fully represent Simone’s writing. There are dozens of other songs (“To Be Young, Gifted, and Black,” “Backlash Blues,” and “I Sing Just to Know I’m Alive” foremost among those missing here). But chosen instead for this compilation are songs closely associated with Simone that she did not write: a traditional gospel (“Take Me to the Water”); one by Rudy Stevenson a longtime member of Simone’s band, who, like her, lives self-exiled in Europe (“I’m Going Back Home”); and a blues by her ex-husband, Andy Stroud (“Be My Husband”), credited on some albums to Simone. She has been fond of medleys since her cocktail-piano days, working her own songs into others’ and sometimes vice versa. Here Simone’s “If You Knew” blends with “Let It Be Me” by Gilbert Becaud, Pierre Declance, and Curtis Mann. On other occasions she has intertwined “If You Knew” with Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s “Mr. Smith.”

This “Mississippi Goddam,” augmented by guitarist Arthur Adams’ sly picking, was taped two decades after Simone’s momentous Carnegie Hall concerts (that “Goddam” is on Simone’s Verve Jazz Masters 17) in a bar and grill on the West Coast. There is a certain poignancy to the fact that the woman who mixed gospel tunes and civil rights compositions on the world concert stage would find her own contributions to the protest song converted into the music of cabaret. This turn of events does not diminish Simone’s songwriting. Quite the contrary, it cements a sense that Simone’s fondest admirers quietly appreciate: that Nina sings Nina for fear that no one else will.

Marc’s original post on Disquiet: Nina Sings Nina

The Disquiet blog: https://disquiet.com/

Subscribe to This Week in Sound

Marc on Twitter: @disquiet