STUFFED (47)

By:

June 26, 2020

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste. STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s collection of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

There’s a lot to worry about these days. Often when people say, Why are you worrying about that? Why not worry about this even worse thing? I say, Don’t sweat it, I’ve got plenty of worry to spread around. Worry, like compassion, is a renewable resource — it doesn’t disappear with use; more often the opposite.

So, in that spirit, I’ve been worrying about restaurants — but, I find, maybe not in the same fashion as other people are worrying. I’ve read general worries about restaurants shutting down, about people moving to the suburbs (eek, white flight! is how I would characterize these, generally), about a disruption in burgeoning foodie culture, about employees (not usually from people who were worried about them BEFORE, though there is plenty to worry about on both counts). Many of these are well-founded concerns, but I’m not sure they really take this moment fully into account. This is a really weird time in restaurant history. To appreciate that, it helps to talk a little about the history of the restaurant, itself a cantankerous, various and opaque phenomenon.

A lot of this “history” hinges on an ongoing semantic argument about what constitutes a restaurant. Is it a place that serves food to the public? Or a place where you order food off a menu? In the 12th century, Chinese cities like Kaifeng and Hangzhou had a variety of restaurants from noodle shops to elaborate spots for the wealthy. Aztec markets had street food, as did Ancient Rome and if you could order and then sit somewhere… The dive bar next to my bookshop, years ago, served canned stew cooked on a hotplate for lunch and this was a restaurant for someone. Coffee houses, inns, taverns and a variety of sit-down, stand-up, and walk-through-on-your-horse spots have always served food, but not precisely in the way Westerners imagine restaurants. This complicated by the fact that we now call fast food places restaurants and take out places restaurants and if those are restaurants then we can back-fill a history of restaurants all the way to the invention of fire.

Anyway, people tend to trace modern restaurants back to France in the late 18th century — the word restaurant (first in English in 1806) was originally a word for a fortifying meat broth served at inns and taverns in France — and there is a direct line from these early French restaurants to today. But it helps to keep in mind that people have been serving food to other people in exchange for payment of some sort since forever, everywhere.

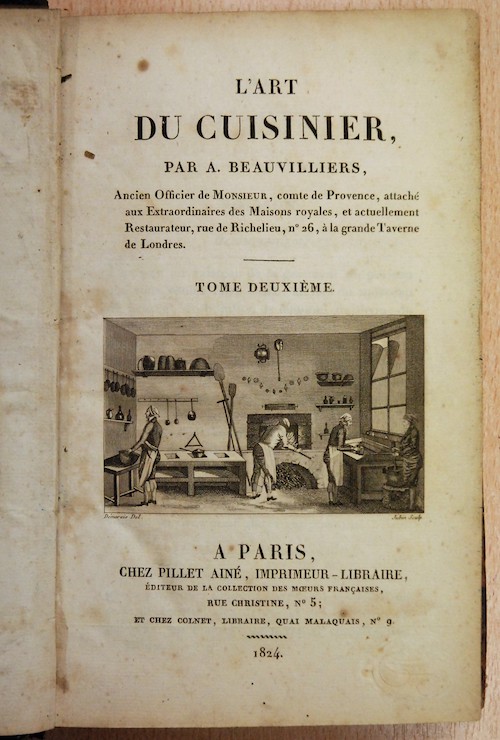

So these first “restaurants” sprang up sometime just before the French Revolution (there are a few claims to the “first” restaurant, none quite compelling) but Antoine Beauvilliers opened the first really noteworthy haute cuisine joint around 1782 in Paris; it was called La Grande Taverne de Londres. It catered to the moneyed class and became, unsurprisingly, a lukewarm bed of conservative, anti-revolutionary politics where goons who favored the royals or a constitutional monarchy would scheme about how not to do much over poulets en chauve-souris. As a result, as the revolution swept Paris, he ended up closing in 1795 for a long spell during which he wrote a good cookbook (L’art du Cuisinier). Interestingly, despite the famous story of Beauvilliers, there has been a persistent narrative tying the invention of the restaurant to royal cooks suddenly freed up by the revolution when they really would have been generally shunned as collaborators and assholes just as Beauvilliers was. It is easier to imagine them fearing for their lives than being embraced by the sans-culottes as restaurateurs, but they did often find work with rich folk in other less volatile European countries (esp. England), which led to the further spread of French cuisine.

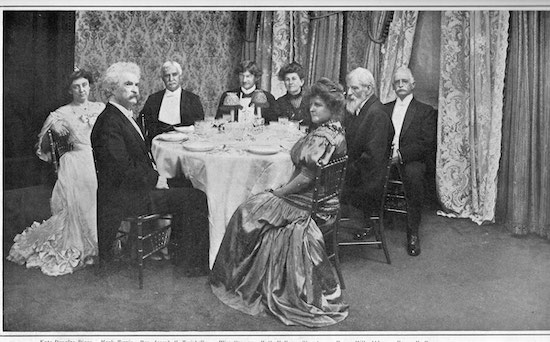

Above: Samuel Clemens’s birthday party at Delmonico’s, 1905

That first wave of French restaurants was wiped away pretty quickly by the revolution only to be replaced by other restaurants — often in the Palais Royale (an open area in the 1st arrondissement near the Louvre) just like Beauvilliers’ — but this time more home to more revolutionary gatherings where they ate langue au gratin, drank too much and planned revolutions and reigns of terror. Some mixture of this first and second wave of French restaurants was exported to London and not too long after the United States where places like Antoine’s in New Orleans, Delmonicos in New York City and Locke-Ober in Boston flourished through the gilded age. When the Great Depression hit, most of the fancy restaurants folded, replaced, slowly, by food carts, automats, diners, places like Schrafft’s which forged a business catering to middle class women (cf. W.H. Auden’s “In Schrafft’s”) or Howard Johnson’s, which, each in turn, have been obliterated by changing fashions; the automobile, fast food, waves of immigrant cuisine. The fortunes of restaurants in Western Europe, of course, have been an exaggeration of even this turmoil, waxing and waning and burning through two World Wars and post war deprivation. The history of the restaurant is a history of cataclysmic change brought on by war, economic collapse, ennui, changes in technology and trade routes. Over all that time, restaurants have served countless purposes, from the revolution and counterrevolution planning of those early Parisian restaurants, seeing and being seen at 17th century London coffee houses (which hardly served coffee, it turns out, mostly booze and food), 20th century diners and dives where novels were written and cigarettes smoked, to 1980s junk bond traders snorting coke in the bathroom at Tavern on the Green.

Restaurants have seen a lot, but the last twenty or so years have been unique.

Since the advent of online shopping, street retail has died a slow death at the hands of disinterest, sloth, “competition” (mostly internet IPO money to burn and sales tax shenanigans) and novelty. In place of all these shops, like fungi on a dead log, have sprung up endless restaurants. There is an argument to be made somewhere that our entire foodie culture didn’t cause all of these restaurants to open but the opposite — we’ve assumed people must be crazy about food, and then acted like we all are, to resolve the strange fact that our cities were suddenly crawling with restaurants. But anyway, restaurants didn’t just replace shops physically, but psychologically. People made trips — in from the suburbs and from all over the world — to cities to eat food and drink craft beers. As a result, restaurants have evolved to fill lots of voids that used to be filled by a variety of retail shops. In my neighborhood, possums, raccoons, and skunks used to be here in profusion. 15 years ago there were thousands of pigeons, but then the falcons ate them all. Now there are just squirrels. The dumpsters here are full of squirrels picking through the remnants of our week’s meals, dragging bagels and drumsticks up trees, secreting half-eaten containers of Kraft macaroni and cheese in the eaves of attics and under newly installed solar panels, wandering through the gutters looking for loose crusts and apple cores. They aren’t great at some of these activities, but they are now the only game in town. I shudder to think what will happen if the coyotes leave.

Restaurants are doing much the same, rushing to fill every corner of our psyches left vacant by the dearth of storefronts. Every welcoming feeling, covetous ache, sneaking twinge of alienation we once felt when walking into a record store, a charming stationery shop, one of those BDSM tinged shoe stores is replicated in restaurants. Anxiety-inducing tapas bars, suspiciously convivial tap rooms, postmodern noodle joints, ersatz dive bars sprung from lost second hand shops, disappeared arcades, and every other space we used to blithely murder time in before we started looking at our phones while rents spun out of control. The death of the mall left an ache at the center of shopping deranged Americans that wasn’t easy to fill and certainly wasn’t going to be assuaged by those outdoor malls that have aggressively (but tastefully) sprung up, but comforting fast casual chains, inexplicable serve-yourself yogurt places and bubble tea outfits will try.

I bet every surviving small retailer in the US has been asked at least 100 times why they don’t add some food and some of them haven’t turned around and murdered someone. Yet. I do feel obliged to mention that a little of this is the fault of Borders and Barnes & Noble who raced to add charmless coffee to their stores as if to shout “Books are stupid but at least we have coffee here which people seem to like.” Assholes. Add that to the fact that, like the cicada, cocktail bars have dug themselves out of the grave for their every twelve-year romp in the sunshine, and you have a recipe for restaurant saturation (though I would have voted for a replacement for banks and gyms before we were done, but…)

Because all of this has happened at internet speed there has been a profusion of sameness even as the breadth (and quality) of food and flavor has exploded. Perhaps born of a creeping fear of bungling customers’ expectations or just not wanting to mess with something that, to all appearances, is working so very very well, this single note sustained in a an imaginary space somewhere between the comfort of the dive bar and the elevated palate of haute cuisine is pervasive. Ten years ago everything looked like it was a bar in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Today, we’ve lost all sense of place entirely — everything looks like it’s in an airport somewhere, as if commercial architects all suddenly decided that it was better to become purveyors of an aggressively banal minimalism than risk being derided for being derivative. Like haute couture, haute cuisine stayed a large part of the food psyche but a comparatively small part of its reality for all of the 20th century. Whether it was cuisine classique or nouvelle cuisine, service Française or service a la Russe, these places were aspirational, hallowed, and not for regular folk. That changed at some point — away with the jacket requirements and verboten blue jeans and in with the bedraggled rich so that often the only way to see if you are dealing with an elevated sort of food is to see if they have a tasting menu or square plates.

And all of this is, to I’m sure no ones shock and surprise, tied up with money, banks, and why places like Bon Appetit, the NY Times food section, The Food Network and nearly everyone else in the foodie industrial complex cater so aggressively to white bourgeois interests. Because that, so often, is who is spending money in the downtown restaurants who have been asked, in multifariously duplicative fashion, to support the entire commercial rent market in big cities. Sure there are countless exceptions, but in the aggregate, restaurants are being designed to suck in the very often white suburban foodie dollars, the instagram market, food media consumers, and while it’s hard to blame them — the only business that seems fully sustainable in this terrible version of America we’ve built is catering directly to the monied class — it left us with this Ponzi scheme of a restaurant industry where the only people really happy are rich people and landlords, a Venn diagram that looks just how you’d expect it to look. The problem, now pretty much diagnosable by anyone this far along in the foodie boom, is that this whole sequence has become self-reinforcing. Landlords want to rent to restaurants, especially well-capitalized restaurants, because they are much less rent-sensitive than retail or any other street-level tenant. Restaurants go in and are suddenly trapped in a feedback loop where they have to please magazines like Bon Appetit, their local food section, instagram influencers, facebook goons, yelp-holes, etc etc, all of which is pointing more or less in the same direction which means the next restaurant and the next and the next is going to — no matter if they have great ideas, brilliant food, the best staff, or the most banal examples of each of those — sort of do whatever seems to be working.

Each of these levels of bias — who gets the bank loans, who is made to feel comfortable (the subtle, and not so subtle, architecture and interior design of alienation), who gets magazine and newspaper and tv coverage — may be invisible (especially if you don’t want to see it) but each serves as a lens to magnify the effects until what is manifested is this sameness aimed unerringly at where everyone decided the money was. And it’s a lot of money. The percentage of food dollars spent in restaurants went from 25% in 1955 to 51% in 2019, in dollars $43 billion in 1970 to $863 billion last year, more than tripling the difference in purchasing power. By number of SBA loans, full service restaurants ranked first, limited service restaurants second and no retailers cracked the top 10 spots. But none of this trillion dollar industry even counts food media — endless television shows, cookbooks, podcasts and related madness, or the cooking implements, $400 fry pans, crock pots seasoned with whale fat, forks hand forged after those in 16th century Dutch paintings, recherche pie crimpers etc. etc.

As always, because there are fundamental structural disparities at the rotten center of this nation, white households have an average net worth 10 times that of black households (with enormously more pronounced disparities in, for example, Boston where white households have on average over 30,000 times the accumulated wealth of African-American families, $247,000 to $8) and because all of this bullshit runs on dollars, the city restaurant landscape is going to be selecting what white people like over and over and over again. Can that be camouflaged by fads for Asian, Caribbean, or Southern food? For tacos and grits and oxtail stew? Sure. Sort of. Though, ultimately, what you see is a gentrification of these ingredients — pork shoulder and sweetbreads and tongue slowly going the way of the chicken wing that used to be almost free and now, idiotically, cost more than thighs.

And the choices that landlords and banks and generic rich people are making have long lasting repercussions. When you rehab a building and make it “nice”, full of nostalgic touches and exposed this and that and copper fiddly bits, essentially the rustic, approachable, currently non-reprehensible version of imported Italian marble and French stained glass and all that gilded age crap, you are making long lasting decisions on who can occupy such a space, who can afford the rent to pay for what it costs to service the loans on that building and that super charming gut rehab. Of course the pressure to turn a profit is always going to create a certain amount of inequality, but these sorts of choices tend to maximize that inequality and lead to what seem like inevitabilities (high rents, certain types of shops and restaurants repeated endlessly in neighborhoods) but are really the result of choices that have been made.

If you’ve survived reading this long, you probably hope I have some clever solution. But alas, I have no idea what is smart or workable. If we spread out the restaurants from downtown into the spots where people actually live, would that help? If people started coming to my neighborhood from the suburbs or on vacation to eat or shop, it would just speed gentrification while annoying the shit out of me (like I, no doubt, annoyed the shit out of people 20 years ago). If food magazines started writing about restaurants outside of city centers, it might just suck in a different way, but clearly something has to give. Commercial rents are a mess, bank and SBA loans are biased and Byzantine and chock full of people gatekeeping a bad system. Maybe this pandemic will shake some of these landlords out of thinking that leaving spots empty indefinitely is better than lowering rent. Maybe city councils will figure out ways to redo zoning that speak to the issues of the 21st century rather than the 19th. The invisible hand of the government is constantly interfering in commerce — e.g. patents, copyrights, licensing standards for various professions all cause goods and services to be enormously more expensive than they would be in a “free” market, but the shops and restaurants that dot our neighborhoods have always been left to fend for themselves. Maybe that’s not as smart as we think. We are swimming in the choices that we’ve made to shape our economy, the drowning is often a choice we make as well.

Above: A dinner at Santopalato, the first Futurist restaurant (Milan, 1931)

Or maybe retail is completely dead, maybe it just gets worse, in which case restaurants will have to evolve to occupy more cultural space. Maybe this isn’t even the crest of restaurants — I have a long history of deciding things are over when they are really just beginning. If restaurants continue to wax, in addition to blunting the impact of what the white bourgeoisie and banks are comfortable with, I would like to see some Futurist smelling restaurants, restaurants where everything is furry (forks, chairs, plates, tables, waiters) or spikey or blue, where people read you Proust while you eat madeleines, or Melville while you don’t eat whales. Wallace Stevens ice cream parlors, Hunter S. Thompson cocktail lounges where you have to wear golf shoes, Italo Calvino joints where you climb trees and refuse to eat snails. Other people will have other ideas.

As unlikely as it seems at the moment, perhaps retail is about to have a rebirth — “buy when there’s blood in the streets” as they say. Then restaurants can go back to being restaurants instead of shouldering such an outsized portion of urban life and geography and consciousness. Either way it would be better for all of us if this shake-out in restaurants led to one where systemic disparities were reduced rather than exaggerated, where workers were paid as if they were holding up entire urban ecosystems instead of just making us breakfast, lunch, and dinner because they have some spare time. All the hand-wringing about the future of restaurants is fine, but it’s good to remember that we can do better.

PHOTO, TOP OF PAGE: The Lunch Box, Cimarron Avenue, Colorado Springs, Colorado (1980, Library of Congress)

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.