OFF-TOPIC (18)

By:

June 8, 2020

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This time, a one-sided oral history lesson with the voices in your headphones, and a meditation on what will become of our artforms and what they will become…

People tend to wonder what kind of culture will “come out of” certain trying times — wars, depressions, 9/11, Trump, COVID. But anyone old enough to remember any such event does not come out of it, they are thrown in — and coming through it is the most pressing interest. The burgeoning theatrical works produced in quarantine are reports from the unknown; unlike the “first drafts” of reaction to a natural disaster or terrorist attack, we don’t know the shape or duration of what we’re going through, even as we are compelled to express it. But surprisingly, the most rewarding examples so far are the ones that stumbled upon the pandemic and its innovative isolations, not those which aim at a lasting statement from the midst of a transient time.

Edward Einhorn’s Performance for One always suggested solitude, in its title and structure (two short monologues delivered by a lone actor to one audience member at a time). The aperture was narrowing, even in the squarely pre-COVID era in which the play started being, in-person, performed. In this way it’s one of two dramas discussed here which feel not so much that they were made for the teleconference medium, as that the medium was waiting for them.

In works like his family-history factual fantasia Doctors Jane and Alexander, Einhorn excels at the meaningfully meta; in his plays medium never overpowers message, though they do dance divinely. The Skype version of Performance for One adapts itself to the special discomforts of its context; the self-consciousness of any live performance, especially one-on-one, migrates to the uncertainty of how to present and react onscreen even in a personal conversation or watch-party, let alone an intimate emotional exchange. This is not arid “theatre as theatre”; in this era of isolation you don’t have much reference to anything but yourself and one or a few others, and Einhorn is conscious of the distances to cross between two minds in any medium (including the consensually real world).

The play’s two parts are single fragments of time, with the artifactual quality that both objects and moments take on in our recollection. The picture-frame telescopes, for the monologue we’re viewing is itself a story about people now past — a deceased dad, a mom fading from disease — and the actor reminds us that she is in fact transmitting someone else (the author)’s memory, which puts yet another outline around the encounter…but these are like ripples in a pond, gaining in distance while carrying some reverberation of the original contact.

A keepsake or photograph can mean nothing to us without the people and events we’d associate with it; Einhorn’s script refers to sense-memories often (the fragrance of his father’s hair, the feel of his mother’s hand in his), and in the role of the storyteller Elizabeth Chappel was a careful and compelling bearer of these fragile flickers from the past, and the fulness of human warmth and emotional forthrightness it takes to incarnate them; even if I were not acquainted with the author, I would feel I spent an infinite 20 minutes with a new longtime friend. It’s a performance of titanic charity and resounding quiet. (The play was originally developed with the always-brilliant actor Yvonne Roen, who alternates with Chappel in the Skype version as well; I opted to venture into the encounter which for me was most unknown.)

The screen puts a literal frame around this conversation, affording a kind of completeness, but Performance for One fills our awareness in ways we can carry with us on that day that we step beyond the lines.

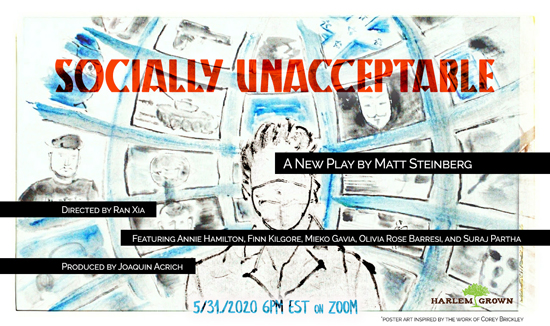

Another production not made for the teleconference medium but born for it was Socially Unacceptable, a play by Matt Steinberg which migrated to zoom in mid-development and which switches our vantage point in the house of mirrors, taking place not in the illusory real-time and direct interpersonal space of Performance for One but fully within the ephemeral landscape of online lives.

We see no one face-to-face, we just see them seeing something (but not what it is) — the play drops us into the dystopian digital workplace of social-media content moderators working remotely even from each other in separate home-office spaces. Monitoring more animal abuse, first-person mass shootings, child porn, hate speech and conspiracy delusion than even the sickest civilian ever consumes, their nondescript workday becomes a vivid hell while the atrocity they witness numbs out to mundanity. But, unlike the military drone operators whose disconnection of distant killing from real-life consequence worries us, the moderators’ daily diet of monstrosity makes them debilitatingly oversensitized.

The dividing line may be feelings of untouchable control versus the inability to affect even your own life; the ensemble of Socially Unacceptable have none, as they scrape at the only job they could find in a nationwide lockdown and depression. This is the indenture that American workers dropped down the abyssal wage-gap have all but stopped noticing, minus the semblance of escape once afforded by vacations or even lunchrooms. So instead the moderators slide into serial nightmares or waking flashbacks, self-injuring or self-medicating to get through the next day.

The workers at times become spectators of each other’s woes, remarking on how high, or stressed, or infatuated, or distracted someone is, but they mostly form a kind of foxhole bond. Manager Elle runs the “pod” like a sergeant, while their cohesion cracks apart. Madeline is desperate for approval, advancement, and a mythical way out of her town; Kyle is financing his whole family and coping with his burdens through a continual weed-induced calm; Joseph is politically principled and sliding into suggestibility and conspiracy paranoia. The boss of all of them, Darriah, talks like a living Myers-Briggs test, knowing everyone’s secrets and weak points and coaxing their confession of any she missed. While struggling to steer the ship and not sink themselves, Elle and Darriah also have secrets to hold over each other — everyone can be reduced to a set of metrics and not one person can’t be mapped; the unknowables are out there in the “real” world, stomping on mice and massacring classrooms, unconstrained and unconcerned. But the moderators can turn them off, or at least their images, and let the site’s customers believe they aren’t there.

Olivia Rose Barresi is both warlike and wounded as Elle, a study in precarious balance; Finn Kilgore is hopelessly well-intentioned with a heartbreaking weary nobility as Kyle; Madeline’s downwardly-mobile anxiety is portrayed with moving intensity by Annie Hamilton; Joseph’s willed innocence and spiral of self-alienation is embodied well by Suraj Partha; and Mieko Gavia’s monumentally conflicted and superhumanly composed reading of involuntary (but not really reluctant) “badguy” Darriah is especially remarkable. Ran Xia’s naturalistic direction suspends any sense of scriptedness while orchestrating Steinberg’s insightful conception with an indelible dramatic imprint.

One by one the characters’ screens go dark and the corporate mind deletes them. But in telling their stories, Socially Unacceptable has shown us something that we ourselves will not be able to forget.

The closest thing to a “commercial” production on this list, What Do We Need to Talk About? by Richard Nelson is also the only one created with the zoom medium in mind. As such, it falls into the familiar pioneer trap of making more of a show of its technology than with it. Nelson’s recurring characters, the Apple Family of Rhinebeck, NY, have a remote reunion peppered with references to zooming and streaming and smartphoning and telecommuting that go about as deep as the product-placement dialogue of the future family in Disney’s Carousel of Progress. The fate of theatre in a mutually-isolated era is brought up often, but it feels pulled in to make an essayistic point (and fill the family’s mostly colorless conversation), rather than entwined with the fabric of the presentation as in Performance for One; that play is self-aware while this one is just self-conscious.

Similarly the exchanges feel stagey where Socially Unacceptable’s felt spontaneous; here there is no crosstalk, no awkwardness, and the dialogue often feels apportioned so as to distribute lines equally among the actors, not to advance narrative or define character. The effect is not that of an informal conversation but of a rehearsed panel-talk or scripted chat-show.

Part of the problem is the topicality of the play’s form but almost none of its content. The Apples are the kind of family that Nelson would not have needed to venture far beyond his desk for reference to even before quarantine contracted the size of our worlds: a government worker, two teachers, an unsuccessful actor, an aspiring writer. They’re like an anonymous, boring version of Salinger’s Glass Family; all of the irritating affluence and none of the intriguing eccentricity. At times the play tries to borrow the substance of other artworks (a moving segment of Bach’s Mass in B minor the family gathers around, an excerpt from Whitman’s “The Wound-Dresser” read by a deceased uncle); these sublime moments are by definition unearned, and the occasional insights of Nelson’s own lack context, like when one Apple sister, Jane, recounts a young person telling her “it feels like the world is ending just as we are arriving.” This strikes a chord with highschool teacher Barbara, who, having recently survived a hospitalization from COVID, is the one member of this whole family who’s experienced an actual problem; the play does begin and end poignantly with her lone screen before anyone has joined her and after everyone has left, checking her looks in the mirror of the camera’s view, wondering if she is still the person her family remembers and that she can recognize. We miss the actual play that should have come between such moments.

Earlier in the day that Socially Unacceptable livestreamed, a thoughtful email went out assuring registered viewers that any Black Lives Matter protests they were participating in should take precedence over the performance. Comparing the valid and very relevant reflection of that play to the triviality of What Do We Need to Talk About?, I felt I had received a disclaimer for the wrong presentation. The main lesson learned from the latter is that there’s a difference between being of-the-moment, and rising to it.

Images (top to bottom): Barresi, Kilgore, Gavia, Hamilton and Partha loving their work in Socially Unacceptable; Chappel in the live (but slightly quarantined-looking) Performance for One, then via Skype one world later; Socially Unacceptable’s poster; birthday simulation with Partha, Kilgore, Hamilton and Barresi; the logo for What Do We Need to Talk About?; and one of its cast’s dangling conversations.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE