Apophenic Adventure

By:

April 27, 2020

In 2013, I devoted a HILOBROW post to the topic of “apophenic adventures.’ Shortly after that, I published a short list of favorite apophenic and treasure-hunt adventures.

Apophenia, I noted at the time, is the unmotivated seeing of connections, accompanied by an experience of an abnormal meaningfulness. All of us seek patterns in random information; apophenics are more likely than others to find such patterns. Adventure stories governed by aophenia aren’t merely paranoid, in other words; they raise such questions as: Does anything mean anything? Can anything mean? I didn’t develop the idea beyond that point; as HILOBROW readers know, I’ve been trying to identify the 1,000 best adventure novels of the 20th century — among other exhaustive lit-list projects.

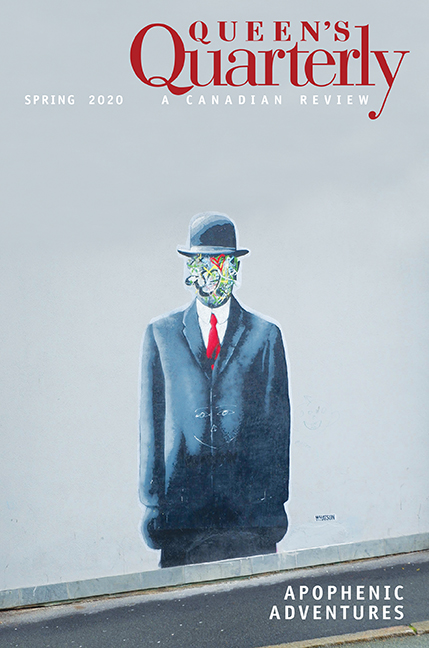

Those of you who were eager to hear more on this topic are in luck! The Spring 2020 issue of the venerable Canadian literary and culture studies journal Queen’s Quarterly, which was guest-edited by HILOBROW friend Mark Kingwell, takes as its theme: APOPHENIC ADVENTURES. In his editor’s note, Mark was kind enough to credit me with inspiring his further interest in theorizing an adventure sub-genre with which he was already familiar:

My friend Joshua Glenn, a Boston-based writer and semiotician, was the first person to articulate in my experience the notion of apophenic adventure. … When I understood what Josh meant by [the concept], or grokked it, for the nerds out there, it made immediate sense and jibed with many of my own intuitions.

Mark’s brilliant essay is a must-read for anyone interested in this adventure sub-genre. However, because Queen’s Quarterly is old-fashioned when it comes to publishing content online, you may have to purchase an actual copy of the print journal. Sorry!

UPDATE: Mark has offered to swap for copies of this issue. See comments, below.

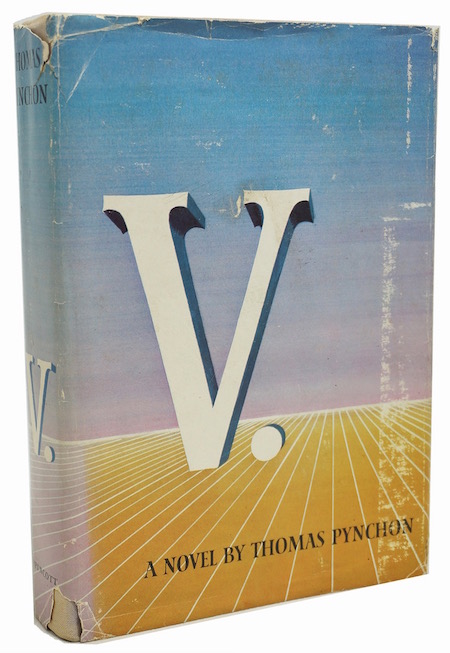

I’ve recommended the following apophenic adventures — many of which resolve, eventually into paranoid thrillers, but a few of which never reveal whodunnit (if anyone dunnit): G. K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday (1908); Earl Derr Biggers’s semi-comical thriller Seven Keys to Baldpate (1913); the works of Kafka; Ethel Lina White’s The Wheel Spins (1936); Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds (1939); Michael Innes’s From London Far (1946) and The Journeying Boy (1949); Alain Robbe-Grillet’s The Erasers (Les Gommes, 1953); Jack Finney’s The Body Snatchers (1954); Muriel Spark‘s Robinson (1958); Philip K. Dick’s Time Out of Joint (1959), Ubik (1969), A Maze of Death (1970); and A Scanner Darkly (1977); Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire (1962); Thomas Pynchon’s V. (1963), The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), and Gravity’s Rainbow (1973); Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris (1961); William Burroughs’s Nova trilogy (1961–1964); Agatha Christie’s At Bertram’s Hotel (1965); Anna Kavan’s Ice (1967); Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo-Jumbo (1972); Richard Condon’s Winter Kills (1974); John le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974); Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren (1975); Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum (1988); Martin Amis’s London Fields (1989). Mark adds additional titles, including some non-adventures.

Mark’s essay also quotes from a 20,000-word email exchange, from Summer 2019, in which he and I (as I mentioned, in September) philosophize about adventure lit. Here is that excerpt:

KINGWELL: Why does adventure give meaning to life? Because what else is there, besides routine and lurking tedium (not to be confused with boredom, as I argue in a recent book)? The absence of desire is death, and nothing speaks to desire more than adventure, even when it is apparently without purpose — hence the appeal of sports, for example, which at once mean everything and nothing in a given moment. Adventure is challenge and reward, risk and redemption. It doesn’t have to be physical or violent. There are romantic adventures, aesthetic and philosophical ones, and spiritual challenges.

But let me ask you a question, since you are a master of categories: Is there a useful typology of adventures? Off the top of my head, I think of: the epic quest, the rescue mission, the heist, the rogue behind-the-lines action, the treasure hunt, the routine sortie gone bad, the secret assignment, the explorer’s discovery, the revenge plot, and so on. Lots of overlap here, but also important shades of difference.

GLENN: You bring up the typology of adventures, and when I gave the subject some thought several years ago, I decided that (a) adventure is always escapist, and (b) each adventure type’s ultimate theme is escape from a particular kind of invisible prison. As a corollary: To the extent that adventure always offers an implicit critique (whether liberal or illiberal) of our postlapsarian world, it is always utopian.

In this analysis, for example, the ROBINSONADE adventure type — the term was coined in 1731 to describe the many imitations of Defoe’s “Robinson Crusoe” — doesn’t have to be set on a desert island or a lonely planet. I’d divide the Robinsonade into three sub-types, each of which involves a kind of prison break: DIY (the protagonist escapes the prison of bourgeois convenience by demonstrating practical survival skills, experimenting and iterating, building from scratch); UN-ALIENATED WORK (the protagonist escapes the prison of wage slavery, and becomes author of their own destiny, decider of their own actions, owner of the value created by their work); and the COZY CATASTROPHE (the protagonist escapes the prison of the modern world, and thrives in a throwback social order that is neo-medieval or even neo-primitive). Can I just mention briefly that Rousseau and Marx were big fans of “Robinson Crusoe”?

The ARGONAUTICA adventure type — I’ve borrowed the moniker from the Greek legend of the quest for the Golden Fleece — can be divided into four sub-types, all of which concern teams of adventurers. In an ALL FOR ONE, ONE FOR ALL adventure, the protagonists are escaping from a state of disharmony — they’re fleeing a balkanized social order or world and joining a like-minded affinity group. (Classic examples — the Camelot legend, the Three Musketeers, The Fellowship of the Ring — see representatives of different kingdoms/regions/races overcoming prejudices to make common cause.) The protagonists of a CRACKERJACKS adventure, meanwhile, are fleeing from a state of UNPROFESSIONALISM, for lack of a better term. These stories — whether they’re about going behind enemy lines on a mission of sabotage, say, or robbing a bank — are about the smooth coming-together of consummate pros, each of whom is super-proficient at one thing. In an ARGONAUT FOLLY adventure, talented adventurers get together for a mission… but they don’t get along, because the same qualities that have driven them to excel make them prickly jerks. And in a BEAUTIFUL LOSERS adventure, finally, our rag-tag team is composed of deeply flawed characters — criminals, outcasts, losers, past-their-prime former adventurers — whose coming-together is haphazard. I enjoy all ARGONAUTICA adventures, but there’s a special place in my heart for the latter sub-type, from “The Dirty Dozen” to “Toy Story.”

I could go on — and will, in later installments of our conversation. But I’d love to hear your thoughts on the above typology, so far, and also to urge you to say more about tedium versus boredom. Why? Because the more I think about adventure and adventure fiction, the more fascinated I become with the ground vs. the figure. I mean the question of what exactly it is that adventurers (and vicariously, fans of adventure fictions) are escaping, why it’s so difficult to break free from that non-adventure condition, and what qualities of body, mind, and character are required for breaking-free.

Mark and I are eager to publish a book whih we’ve tentatively titled The Adventurer’s Glossary. We’ve lined up the great cartoonist Seth to contribute illustrations and decorations. (This would be a sequel to our The Idler’s Glossary and The Wage Slave’s Glossary.) My own contribution to the book is mostly complete, at this point. Any interested publishers, out there?

20 ADVENTURE THEMES AND MEMES: Index to All Adventure Lists | Introduction to Adventure Themes & Memes Series | Index to Entire Series | The Robinsonade (theme: DIY) | The Robinsonade (theme: Un-Alienated Work) | The Robinsonade (theme: Cozy Catastrophe) | The Argonautica (theme: All for One, One for All) | The Argonautica (theme: Crackerjacks) | The Argonautica (theme: Argonaut Folly) | The Argonautica (theme: Beautiful Losers) | The Treasure Hunt | The Frontier Epic | The Picaresque | The Avenger Drama (theme: Secret Identity) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Self-Liberation) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Reluctant Bad-Ass) | The Atavistic Epic | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Artful Dodger) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Conspiracy Theory) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Apophenia) | The Survival Epic | The Ruritanian Fantasy | The Escapade