10 Best Adventures of 1989

By:

April 25, 2020

Thirty-one years ago, the following 10 adventures from the Eighties (1984–1993) were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- Philip Kerr’s Berlin Noir historical crime adventure March Violets. Three years after Germany’s Reichstag Fire Decree and Enabling Act abolished most civil liberties and transformed Hitler’s government into a legal dictatorship, ex-Berlin cop and Army vet turned private eye Bernie Gunther is hired by a steel magnate to find a diamond necklace stolen from his murdered daughter. The assignment forces the cynical Gunther to confront corruption among the Third Reich’s civil servants, the Nazis’ everyday violence and anti-Semitism, and the opportunism of the Nazi “March violets” more interested in profit than ideology. As the city’s most offensive aspects are temporarily sanitized for spectators arriving for the ’36 Olympic Games, our neo-noir protagonist traverses seedy dives and opulent mansions, trying without much success to stay out of political hot water. Protected only by his native wit and WWI medal, Gunther runs afoul of police, Gestapo, gangsters, and government officials. There’s an aristocrat collecting blackmail material on important personalities for Hermann Göring, a safecracker, a corrupt anti-corruption official, and — in the best noir tradition — a shocking family secret, and a sexy assistant. When Gunther is sent to the Dachau concentration camp, will he assist a Gestapo investigation in order to save his own neck? Fun facts: Shout-out to HILOBROW friend Tony Leone, who recommended these books to me. The second installment in the trilogy is The Pale Criminal (1990); the third is A German Requiem (1991).

- Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s historical-crime graphic novel From Hell (1989–1996). A comic that is difficult to read — not only because of the graphic violence, but literally, because Eddie Campbell’s black-and-white art is crabbed, crowded, and scratchy, like the mind of a maniac. Also, Moore’s nearly 600-page meditation on the identity and motives of “Jack the Ripper,” the still-unidentified serial killer active in the impoverished areas in and around London’s Whitechapel district in 1888, is complex. Inspired by Douglas Adams’s notion of solving crimes “holistically,” Moore sets about “solving” Victorian-era British society — in whose injustice, racism, and casual violence he locates the origin of every variety of 20th-century horror. From Hell takes as its premise the — unproven, evocative, self-parodying — theory that the Whitechapel murders were the work of royal physician Sir William Gull, who was conspiring with the British royal family to conceal the birth of an illegitimate child, to Annie Crook, a shop girl, fathered by Prince Albert Victor. When a group of prostitutes — Annie’s friends — threaten to reveal the prince’s secret, Gull begins a campaign of violence against them. He justifies the murders by claiming they are a Masonic warning to an Illuminati threat to the throne; the story’s psychogeography, which reveals the hidden mystic significance of London landmarks, owes a debt to Iain Sinclair’s White Chapell, Scarlet Tracings, though Sinclair was also influenced by Moore. Like other brilliant, difficult comics of the era, readers may yearn for explanatory footnotes; not to worry — the collected edition features over 40 pages of additional info. Fun facts: Loosely adapted as a not-very-good 2001 film, made by the Hughes brothers, and starring Johnny Depp, Heather Graham, and Ian Holm. The series was published in ten volumes between 1991 and 1996. The series and an appendix were collected in a trade paperback and published by Eddie Campbell Comics in 1999.

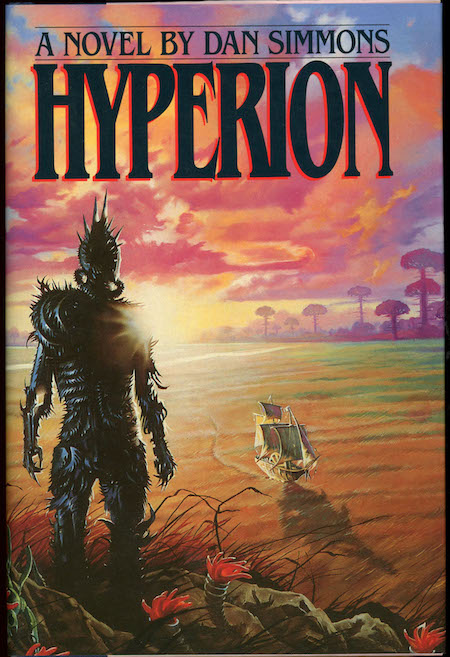

- Dan Simmons’s Hyperion Cantos sci-fi adventure Hyperion. Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales is a collection of stories — told by a disparate group of pilgrims — within a frame story, the overall effect of which is to paint a sardonic portrait of 14th-century English society. This 29th-century Chaucerian space opera gives us a priest, a soldier, a poet, a scholar, and other pilgrims chosen by the Shrike Church and the Hegemony of Man (which rules some 200 human-inhabited planets) to make a request of the so-called Shrike, a deadly half-mechanical, half-organic creature that can control the flow of time. As they progress in their journey, away from their home planets (simulacra of ancient Earth societies and cultures) towards the remote, titular planet Hyperion, where the mysterious Shrike dwells, we learn — via the pilgrims’ stories — that the Ousters, a faction of humanity mutated by centuries of living in deep space, plans to invade Hyperion… and that Hyperion’s enormous, provocatively empty Time Tombs are about to finally reveal their secrets. Earth has reportedly been destroyed; the Hegemony’s technology (strikingly, readily available teleportation devices) comes from a secretive civilization of self-aware AIs, who inhabit a cyberspace-esque realm that is divided into warring factions. There’s a legend suggesting that all but one of a group of pilgrims to the Shrike will be horribly killed, and the other granted one wish; why has this group of individuals been selected for this mission? It’s a metatextual novel: The astute reader will pick up allusions to everything from Shakespeare to The Long Goodbye and The Wizard of Oz, and of course to other sci-fi novels. And it’s a literary work, too: Each novella mashes up genres, from the detective story and horror to action-packed combat, even romance. Phew! Fun facts: Winner of the Hugo and Locus Awards. The next book in the series was The Fall of Hyperion, published in 1990.

- Grant Morrison and Richard Case’s Doom Patrol comic (1989–1993). “Le Poète est semblable au prince des nuées/Qui hante la tempête et se rit de l’archer,” laments Baudelaire, in “L’Albatros.” “Exilé sur le sol au milieu des huées,/Ses ailes de géant l’empêchent de marcher.” The Doom Patrol, as the superhero team first appeared in DC’s My Greatest Adventure #80 (June 1963), could relate. The Chief, a wealthy, paraplegic, brilliant scientist-inventor; Robotman, a former daredevil and race-car driver turned cyborg; Elasti-Girl, a former athlete and actress who can expand or shrink her body at will; and Negative Man, a former test pilot who can release a negatively charged energy being from his body — they perceive their so-called gifts as a curse, dooming them to a life of alienation. Scottish comic book writer Grant Morrison, part of the far-out British Invasion of American comics that included as Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman, took over the relaunched Doom Patrol series in 1989; DC stopped submitting the title to the CCA for approval around that time. The resulting run — from issues 19 through 63 — was wild. The Chief (whom, we will later discover, may have had something nefarious to do with the origin stories of his comrades) leads Robotman (a brain, remember, trapped in a body without nerves), Rebis (a queer, transgender, transracial entity combining Negative Man, his energy spirit, and Eleanor Poole, a black doctor), Crazy Jane (a victim of sexual abuse; each of her 64 alternate personalities has a different super-power), and a monkey-ish psychic named Dorothy against the Scissormen — metatextual, Struwwelpeter-like inquisitors who worship a god that exists at the crossroads where realities meet, and whose cut-up dialogue reads like Dada poetry. Ultimately, the Doom Patrol’s weirdness proves to be the key to its effectiveness: They often team up with so-called villains in order to combat the neo-fascist, Foucauldian forces that police sexual identity and gender norms. Richard Case’s trippy artwork is simultaneously engaging and nightmare-inducing. Fun facts: The last line of Morrison’s run quotes the Smiths’ “Asleep”: “There is another world/There is a better world/Well, there must be….” It’s a beautiful statement of revolutionary optimism for an era that had largely abandoned utopian idealism.

- John le Carré’s espionage adventure The Russia House. Written during Perestroika — the political movement for reformation within Mikhail Gorbachev’s Communist Party, which would lead to the revolutions of 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union — The Russia House would have us understand that the Cold War, by that point, was sustained by intelligence agencies, the military, and the military–industrial complex, none of whom could afford to admit that the Soviet Union was no longer a threat. Our protagonist, “Barley” Blair, a British publisher, musician, and bon vivant, is contacted by a beautiful Russian woman, Katya; her friend, Yakov, wishes Barley to publish a manuscript detailing Soviet nuclear capabilities and atomic secrets. When the MS ends up at the Russian House — that is, the MI6 section devoted to spying on the Soviet Union — Barley is manipulated into acting as a go-between. The Russia House wants to know more about the source of this intel; Barley, however, falls for the widowed Katya and her kids, and wants to smuggle them out. The CIA and MI6 help Barley set up a meeting with Yakov’s KGB captors/handlers — nobody can be sure — but Barley and Katya have other plans. “The old isms were dead, the contest between Communism and capitalism had ended in a wet whimper. Its rhetoric had fled underground into the secret chambers of the grey men, who were still dancing away long after the music had ended.” Fun facts: A 1990 adaptation, directed by Fred Schepisi, starred Sean Connery and Michelle Pfeiffer. Not the greatest movie, but notable for its score — Russian music and jazz — by Jerry Goldsmith, and because it was one of the first western films to be shot on location in the Soviet Union.

- Katherine Dunn’s sci-fi/horror adventure Geek Love. The Binewskis are in the traveling circus business; to that end, father and mother have used amphetamines, arsenic, and radioisotopes on their unborn children… purposely breeding a one-family freak show. Arturo, who has flippers for limbs, is known as Aquaboy; Iphigenia and Electra are conjoined twins; and Olympia, the book’s narrator, is an albino hunchback. Only Chick, the youngest, appears unremarkable. There are two story lines, here. One, a picaresque set in the past, follows the family from town to town as the kids get older. Arty, a megalomaniac, founds a cult (“Arturism”) devoted to the pursuit of “Peace, Isolation, Purity” by means of limb-amputation; his one-man freak show threatens the Binewskis’ livelihood, which leads to strife. The other story, set in the present, is an Imitation of Life-esque melodrama about Oly’s daughter, Miranda, who was abandoned as an infant. Miranda has fallen into the clutches of a deranged wealthy woman who wants the teenager to undergo cosmetic surgery, to make her look “normal.” And then there’s the saga of Chick, whose telekinetic power is terrifying. Fun facts: This book was a big deal, among some of us, when it appeared; it predicted the carnivalesque atmosphere of 1990s-era youth culture. And Dunn, a terrific writer unlike any other, came out of nowhere. Even the cover art — designed by Chip Kidd — was ahead of its time, eschewing “good” typography and illustration for… something weird, “lame.” Tim Burton aquired the film rights, at one point; the Wachowskis — cool, confident freaks who could have been Binewskis — were also interested.

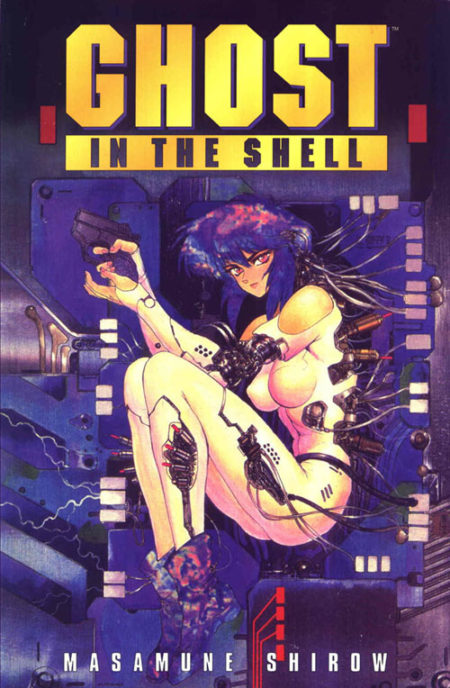

- Masamune Shirow’s seinen manga sci-fi series 攻殻機動隊 (Mobile Armored Riot Police; in the US: Ghost in the Shell (1989–1990). Public Security Section 9 is a counter-cybercrime organization, in mid-21st-century New Port City, Japan — led by Major Motoko Kusanagi — a synthetic “full-body prosthesis” augmented-cybernetic human. Thanks to her wetware (a computer user interface implant located in her cranium’s suboccipital nerve region), Kusanagi’s mind can seamlessly interact with mobile devices, machines, and networks; although her brain is a century old, her prosthetic body is one of the most advanced models on the market. So she’s not only the best hacker on her team, which is composed of former police and military types, she’s also the toughest; also, because the comic was published by the laddish Japanese manga anthology Weekly Young Magazine, Kusanagi is a slapstick, sexy character (think Tank Girl) fascinated by “human” vices. Villains include the Puppeteer, who has mastered the art of “ghost hacking” people’s cyberbrains and forcing them to commit crimes by proxy (and who turns out to be something much worse than a mere crook); as well as neo-noir corrupt officials and sinister corporate types. Shirow’s dynamic black and white drawings are simultaneously silly and hardboiled, detailed and gestural; the comic is too grown-up for kids, too child-like for grownups — perfect! Fun facts: Manga artist-author Masanori Ota’s pen name is derived from the legendary sword-smith Masamune. Ghost in the Shell was released in tankōbon (stand-alone) form in 1991; in 1995, Dark Horse serialized the series in English. The 2017 movie adaptation was criticized because it cast Scarlett Johansson in the lead role; also, Evan Narcisse of io9 lamented that the movie version of Kusanagi asks the wrong sort of existential questions about herself.

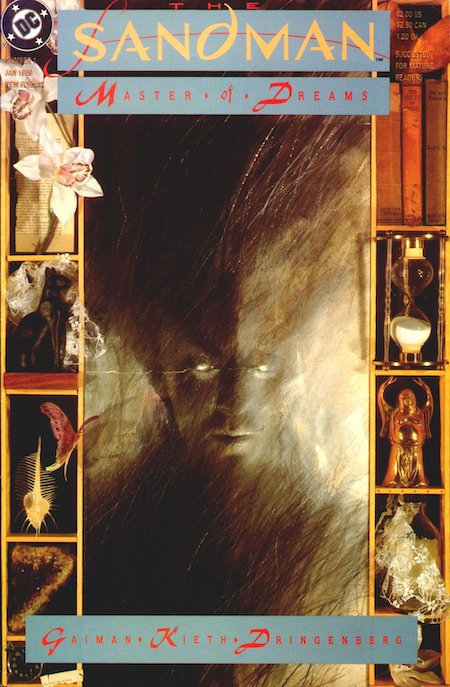

- Neil Gaiman’s occult fantasy comic The Sandman (1989–1996). In 1988, Neil Gaiman — a British comics writer who’d recently begun working for DC — proposed to reboot Joe Simon and Jack Kirby’s 1974–1976 series The Sandman. Instead, DC editor Karen Berger challenged him to “keep the name, but the rest is up to you.” Working within these Oulipian restraints, Gaimain wrote a 75-issue series that became a cult success, particularly among a younger, mostly female readership who (up to that point, anyway) didn’t read comics. Inspired in part by James Branch Cabell’s 1919 meta-mythical adventure Jurgen, Gaiman recounted the tale of Dream/Morpheus/Sandman, the haughty, cruel, and ancient anthropomorphic personification of dreams… who escapes after 70 years in captivity and sets about restoring his kingdom, the Dreamworld. As he searches for his lost objects of power, Morpheus genre-hops — from myth to pulp fiction, and everywhere in-between. Also, Gaiman inserts pop culture and literary references and jokes into nearly every panel. It’s a dazzling display of high-lowbrow literary fandom… one leaving even the most well-read fan wishing for extensive, Chester Brown-esque footnotes… which, thankfully, are now available via annotated editions. Sam Kieth, Mike Dringenberg, Jill Thompson, and others contributed appropriately eerie and amusing art, with lettering by Todd Klein and covers by Dave McKean. Fun facts: Comics historian Les Daniels has called the series “a mixture of fantasy, horror, and ironic humor such as comic books had never seen before.” Along with Maus, Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns, The Sandman was one of the first graphic novels ever to be on the New York Times Best Seller list. A Netflix adaptation is underway.

- Octavia E. Butler‘s Xenogenesis sci-fi adventure Imago. In the final installment in Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy, the future of not only Earth’s surviving humans but their alien captors/saviors, the tentacled Oankali, is at stake; can Jodahs, a half-human, half-Oankali ooloi (a genderless figure, who makes satisfying sexual relations between men and women — whether Oankali, modified human, or hybrid — possible) mature successfully into its adult form? Concerned that our protagonist will inadvertently contaminate them before it learns to control its genetic manipulation abilities, the Oankali send Jodahs to live in the woods. Here, we finally discover that the seemingly unemotional, almost clinical alien invaders need and long for (emotionally, sexually) relationships with humans. In fact, Oankali and modified humans alike can’t stand to touch members of the opposite sex without the mediation of an ooloi; and this mediation becomes addictive, for Jodahs, who experiences its exile as torment. Jodahs is also tortured by its inability to fit into any group — so when it encounters two human siblings, Jesusa and Tomas, it forms a new family unit. The book is erotic without being explicit, and despite one’s horror/revulsion at this post/evolved-human state of affairs, we care enough about the characters and their struggles to root for everything to work out. Will Earth’s humans, in the end, be as accepting of the Oankali as we are? Fun facts: As in the first two Xenogenesis books (1987’s Dawn and 1988’s Adulthood Rites), Butler asks us to grapple with unsettling issues of consent, coercion, and enslavement. Some readers find this book too philosophical; others think it’s the best of the trilogy.

- Martin Amis‘s apophenic crime adventure London Fields. When Samson Young, an uncreative and dying New York writer, moves into the posh London apartment of a famous British author (whose initials happen to be the same as Martin Amis’s), he discovers the diaries of Nicola Six. Nicola, a femme fatale who hopes to die before she gets old, claims she’s manipulating two married men — Keith Talent, a Cockney hooligan obsessed with pornography and darts; and Guy Clinch, a yuppie who can’t resist a sob story — into murdering her. She’s set the date; the countdown has begun. The year is 1999, which sort of makes this a sci-fi tale — and indeed, in the background of this brilliant, tedious, hilarious, exasperating story lurks some kind of atomic disaster which threatens to destabilize the planet. But our focus, here, is very local. Nicola, Keith, and Guy inhabit the same gentrifying neighborhood; Samson ends up coming into contact with each of them… and manipulating their story, in order to finally write a novel. Or is he being manipulated? Long, ambitious, misanthropic, and hard to put down. Perhaps the most remarkable character is a destructive toddler. PS: This is the only Amis novel to include every one of the author’s tropes, according to a 2019 Guardian essay: “Apocalypse, authorial intrusion, [a character named] Keith, sex, time, twins, yobs (jackpot!)” Fun facts: Adapted as a 2018 movie directed by Mathew Cullen, and starring Billy Bob Thornton, Amber Heard, Jim Sturgess, and Theo James. “Novelistic, rich and awfully silly,” opined The Guardian, “[Cullen’s] London Fields – like Ben Wheatley’s take on High Rise – is a long-awaited adaptation of a popular and gloomily prophetic book, that seems unnecessary.”

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.