TEN DAYS (DAY NINE)

By:

April 15, 2020

My grandfather used to tell me an old story about a similar situation to the one we are in (minus the toilet paper worries, I suppose). Some of the detail is hazy, but a town was on lockdown for some reason:

Maybe it was even an outbreak of some disease—the plague, or cholera, or leprosy—but I feel like the town was under actual rather than metaphorical siege, that they’d abandoned their fields and crushed inside the old walls to wait out the depredations. Whatever the reason for it, lots of different people were huddled there—either it was a town on an important trade route, or maybe the attacking force had pushed all sorts of people from all over in front of them and this is where everyone ended up; smashed together in this old, walled town, or they were the remnants of a far flung empire wracked by plague. Whichever it was, the people were wary of going outside—disease, arrows, catapult and trebuchet stones, artillery, something was keeping them contained, so they had to organize by shouting or passing notes or elaborate hand gestures. Somehow, over a couple days, maybe, a few things became clear: they were going to be stuck in there, both inside their houses and inside the wall, for some time; supplies were unequally and inadequately distributed (e.g. some people had meat, some vegetables, some easy access to the town well, some had chickens, some spices, fish, plenty of people didn’t have too much of anything, etc. etc.).

“So”, my grandfather would say, “what do you think they did?”. Eager, ingenuous child that I was, I would shout something like “Did they share with each other?”

As shaky as my memory is of this story, I remember vividly how my grandfather would look at me, pleased, but a little sad, and say “That’s right. They would pool their resources.”

They set up a system where big cauldrons (probably 2 or 3) were filled with water and put over a fire. Set up in some big covered space where a fire could be made relatively safely. People would run over, one at a time, shouts and hand signals directing them when it was clear, and one by one they would tend the fires and drop whatever they had in the pots. A woman nearby would organize the drops. “What’s that you have?” and they would shout out “Parsnips!” or “Thyme!” or “Lamprey!” and she would tell them which pot to drop it into, “Mutton bones!”, “Onions!”, “Juniper!”, and the pots would be filled in turn, “Mushrooms!”, “Squirrels!”, “Carrots!”, and people would cheer or make playfully critical remarks. It took all day and a little into the night for the stews to be done, partly because it took awhile to move everyone and their ingredients around the town in a more or less safe manner, and partly because these were very big pots of stew and, often, really tough cuts of meat. Still, the first day of stew was delicious and whether it was hunger or cooperation or the genius of that conveniently domiciled chef, no one really cared.

As the days stretched on and their confinement continued, the stews became increasingly difficult to put together. Ingredients dwindled, people who were inclined to be cheap and hold what food they had close, became more inclined in that direction, and people who had started with little found they now had nothing. Plus, many of the inhabitants were taking this opportunity not to sneak over to put food in the pot, but to put some food in someone’s pot, if you know what I mean.

My grandfather thought it was hilarious to make sexual innuendos, especially as I grew into an awkward teenager and would fidget uncomfortably.

Some affairs continued and many more were started as men and women with an armful of squash or fava beans were waylaid for hungers of a more immediate nature—people only have so much attentiveness, after all. But others cajoled and shouted and improvised ingredients and made do and waited out the lovemaking, and while the first stews might have been thick with meat and fish and vegetables and layered with the flavors of fresh herbs, the stews in week three were cleverly held together with salt and chile peppers, reused hunks of salt pork and forgotten pieces of pemmican and dried fish dug out of the backs of cupboards and were also delightful. So the town ate through the weeks and as they did, a funny thing happened. As the food dwindled and as everyone was forced to scrape together forgotten bits of food, it became a little easier. That sack of potatoes tucked away in week one, just in case, was brought out happily. An aged sirloin, a smoked ham, and a trove of rutabagas were somehow discovered. The trysts were also becoming both more desperate and more elaborate as time went on, positions and partners and improvised locations ricocheting off each other, at all hours, so that a seemingly constant low moan was added to the low simmer of the stew. As a result, the last stew was nearly as good as the first, especially since they kept saving the leavings and sediment and feeding it back into the next stew, and nearly everyone was sleeping better.

For a time, it seemed like they could roll around sweatily and eat stew forever.

My grandfather would pause here and I was supposed to ask. “Last stew? And then what happened”, but sometimes I didn’t want to. So we would sit, enjoying the flavors of this last stew, imagining how weeks of detritus and melted down meat and vegetable would survive and leap from one week to the next, keeping memories of past stews alive only to be eaten again and again and again. Eventually these imaginings would start to get gruesome, or the stew and the sex would start to get uncomfortably conflated in my head, and finally, I would ask it.

”Well, I don’t think they made it.”

“WHAT???”, I’d always try to put the incredulity I felt the first time into my voice, which wasn’t really very hard.

“I mean, look how good they did! They didn’t ultimately escape, but they did great. Really great.”

And we would look at each other, cautiously, wondering if anyone would say, “Well someone made it out to tell the story, at least, right?” But we wouldn’t do it.

I don’t have any of the stew recipes from this story, I guess no one does, but there is this:

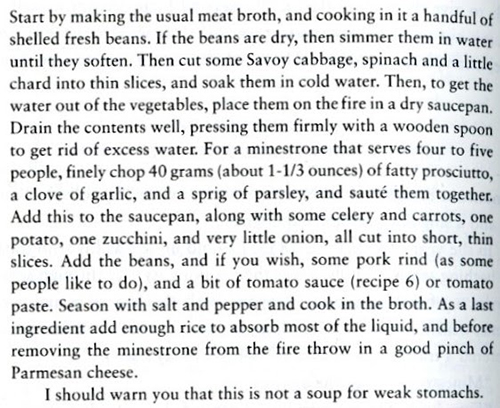

Pellegrino Artusi, in his persistently digressive 1891 cookery, La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangiar bene—the first great Italian cookbook—tells a story about visiting Livorno and eating the soup of the day, minestrone, at a trattoria. He ate, retired to his room at a villa run by a Mr. Domenici, and was sick all night, going from bed to bathroom cursing the minestrone “Damned minestrone, you will never fool me again!” throughout the night. In the morning he took a train out of town and quickly recovered but soon learned of a massive cholera outbreak in Livorno.

Artusi, somehow, pivots directly from this story into the minestrone recipe: “the first to be struck dead was Domenici himself. And to think that I blamed the minestrone! After three attempts, improving upon the dish each time, this is how I like to make it.”

Series: TEN DAYS on HILOBROW