OFF-TOPIC (15)

By:

February 14, 2020

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This time, a season-specific Valentine to one of pop-culture’s most meaningful missed connections…

Old loves can seem like much happier times in retrospect, and the labors of artist Jack Kirby — best known for defining the superhero form but just as significant for having co-invented romance comics — grow more cherished over time. Supposed commercial failures like his cosmic Fourth World cycle come to be revered as cultural milestones, so it makes sense that the comics he didn’t even get into print are considered lost masterworks.

I for one have been waiting all my life for one of his legendary passion projects. Kirby had been trying to help comics grow up since the 1950s, when he and Joe Simon started a line of books in genres more familiar from grownup pop-media — Westerns, war, police-procedural and romantic soap-opera — for former boys who’d seen battle and former girls who were asserting the importance of their inner life. This venture was ironically swept under by a manufactured political panic over comics being a bad influence on kids. By the end of the ’60s when those kids had grown up to demand more substance in their leaders and more truth in their mass culture, Kirby attempted the “Speak-Out Series” of quasi-journalistic comics addressing social issues, marketed to 18-and-ups, and distributed with “real” magazines instead of on the comicbook racks.

Once again, Kirby was looking beyond the borders of his medium’s frame of reference, like some newspaper cartoon-strip character become self-aware and peeking outside the boxes to the current events right next to him. The self-help era was in bloom and one of Kirby’s responses was a concept fated to be unrequited but fabled for decades thereafter: True-Life Divorce. This was not your parents’ romance comics — but for the generation that would have read it, it was your parents’ story. Regardless of Simon & Kirby’s ill-starred ’50s publishing venture, the Young Romance title they’d started for another imprint in 1947 was a sensation that spawned scores of imitators and kept the comics industry alive. Melodrama would recur as tragedy with True-Life Divorce’s tales of decidedly unromantic middle-age.

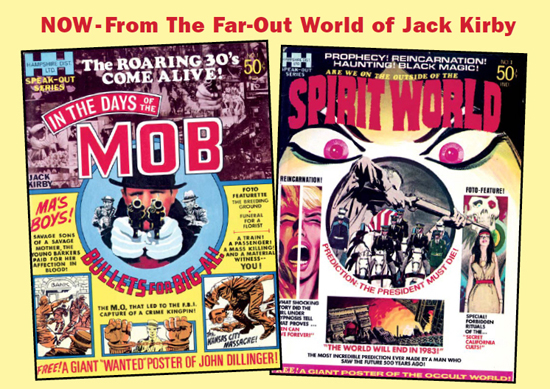

But DC Comics left Kirby at the altar long before that story could begin. His vision of larger-sized, magazine-quality comics in full color and with high-end advertisers and other contributors from respected media like books and movies had already been downgraded to cheap black-and-white volumes produced by Kirby alone (to fill his own contract) and distributed almost nowhere and without even the DC logo on them. One issue each of In the Days of the Mob (about 1930s gangsters) and Spirit World (about paranormal activity) made it out, cancelled a year or two before The Godfather and The Exorcist movies would transform American pop culture; True-Life Divorce died on the drawing board.

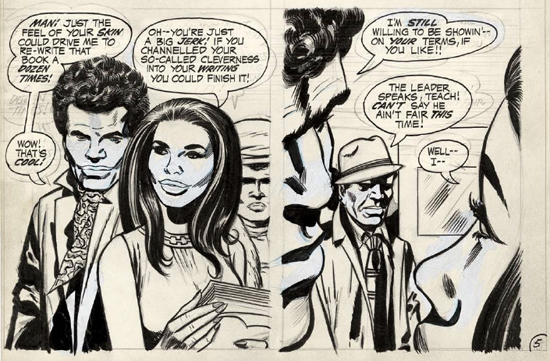

DC did try to rob its grave a bit, though. Kirby, the co-creator of Marvel’s Black Panther, had included one story starring African American characters in True-Life Divorce; the bean-counters picked this one out and put Kirby to work on a book’s-worth of Black-interest stories, with grandiose plans of involving pop-star Roberta Flack as a celebrity tie-in (“free giant poster!”) and their eyes on poaching some of the audience for Ebony and Jet. Kirby tried to back off and refer DC to promising Black comic artists he knew, but this inclusive outlook, now as commonplace as the novelists and TV-showrunners who regularly write comics, was just as alien to Management, and Kirby had a contract to be stuck to. In due course the powers that be deemed the characters’ faces “too realistic” and had them redrawn closer to acceptability and/or stereotype; Flack’s people enthusiastically passed; and Soul Love was shelved forever.

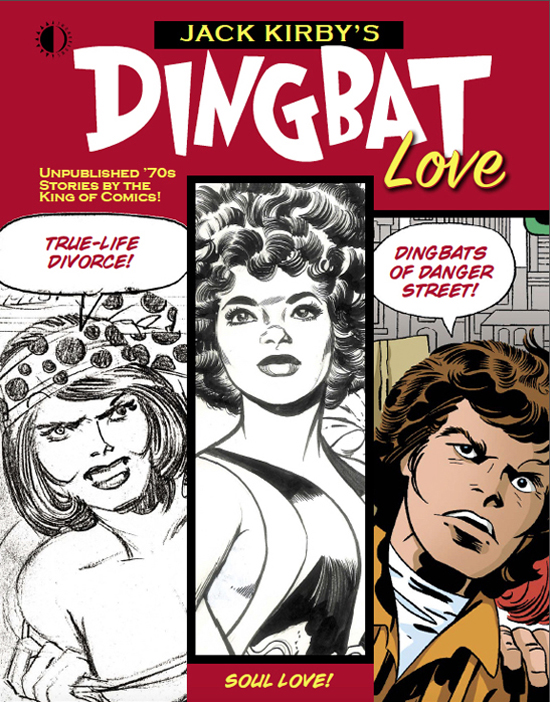

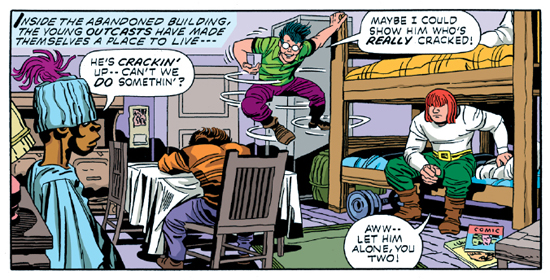

But forever only lasts so long, and all existing remnants of both Soul Love and True-Life Divorce — as well as two never-published issues of another Kirby rarity, The Dingbats of Danger Street — have just surfaced in the loving reconstructions of Jack Kirby’s Dingbat Love from TwoMorrows Publishing (for whom, full-disclosure, I am a columnist — but not a fifth-columnist; I wrote nothing for the book). The Dingbats is a long story in itself; unlike the stillborn Speak-Out books, this was slated as an ongoing, conventional-format comicbook, but got caught up in a general contraction of DC and the industry in the mid-1970s. Still, it intersected with the kinds of issues Kirby’s cultural radar was always sweeping for; an update of another genre Simon & Kirby had brought to comics in the 1940s, the “kid gang” form (adapted from urban-urchin movie franchises like The Dead End Kids), Dingbats was about a band of homeless, squatter street-kids, getting into absurd scraps and living at the opposite dead-end of various traumas and abandonments. It was Kirby’s channeling of his own warlike tenement childhood, seemingly filtered through the sassy “delinquents” of West Side Story; a genealogy of slapstick tragedy left to fend for itself in the socially-unconscious mid-’70s.

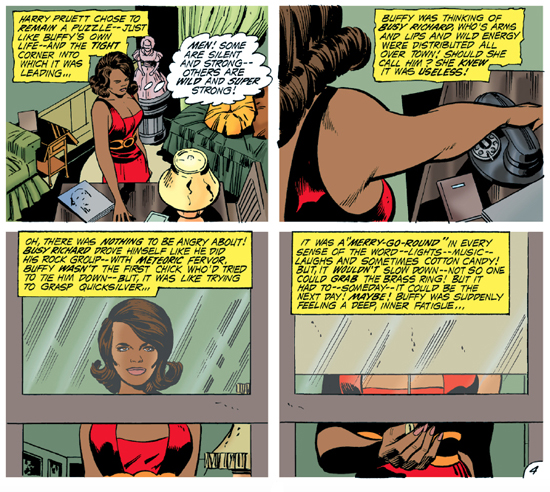

In Dingbat Love’s inspired curatorial design, these recovered memories of Kirby waver in and out of resolution; most of True-Life Divorce’s pages remain in their original, pure-pencil state of nature; some of The Dingbats is seen in its prototype pages side-by-side with counterparts fully worked up from the inks that were actually applied before the whole book went into hiding; Soul Love (perhaps judged the content needing most help) is reconstructed in a full simulation of what the first, high-end 1971 issue could have looked like.

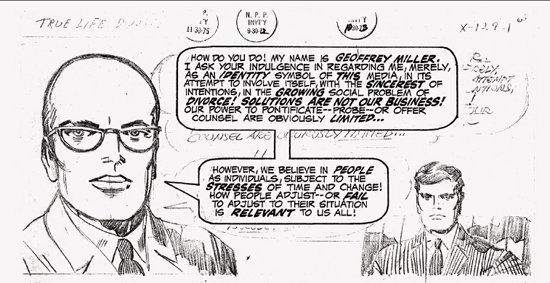

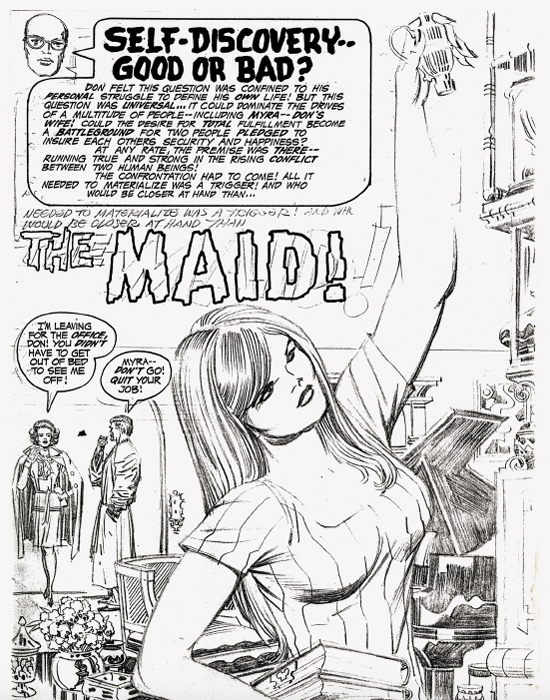

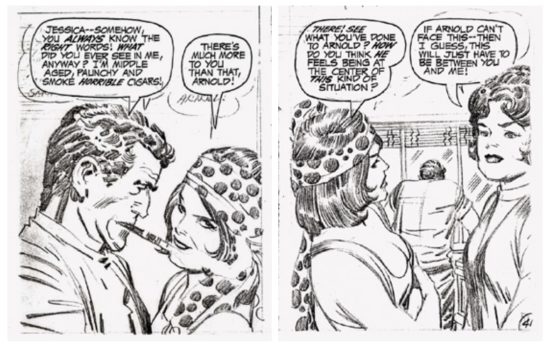

The True-Life Divorce pages are a fascinating chapter of missing history, at a crossroads between the authoritarian control-voice of pre-’60s society and the therapeutic inner voice of its “liberated” aftermath. In this higher-order form of storytelling, Kirby is astonishingly meta from the opening line, with a guide who seems self-aware of his nature as a narrative construct, counselor Geoffrey Miller: “I ask your indulgence in regarding me, merely, as an identity symbol of this media.” He’s a valuable counterbalance to characters who don’t even seem to know the details of their own story, let alone what tracks they’ve gotten trapped in. The erasures are disorienting, but seem advised — watching midcentury sitcoms as a kid, we made a running joke of the mysteriousness of whatever it was the dads actually did; fathers like Ward Cleaver were seen shifting paper at desks and sending commands into intercoms whose purpose was never detailed. Kirby, who went from poor slum kid and army draftee to a lifetime in precarious freelance art, seems to have seen the corporate work of the conformist 1950s and ’60s as an interchangeable blank that masses of people sleepwalked through; in True-Life Divorce’s first story, “The Maid,” suburban husband Don has “quit the rat-race” and lingers in his bathrobe while wife Myra has “taken a job with a large firm”; Don is waiting for a “deal” to work out, and later his “proposition” is accepted, but Myra is absorbed with her executive position, “the ‘log jam’ that tied us up in conference all day,” and a “plan” which then “goes over big.” The dreamlike lack of detail, though, gives Kirby the space for sharp insights into changing human circumstance and unchanging human nature; Don is aware that Myra’s job has “given her challenges she never had as a housewife,” and Kirby (or, y’know, “Geoffrey Miller”) is aware of Don’s self-deceptions: shortly before making a pass at the couple’s 22-year-old cleaning lady, Ingrid, a caption observes that “Unlike Myra, Don treated Ingrid as a friend rather than an employee. He was at war with the status game — and Ingrid was his way of proving it! At least, this was Don’s rationale at that moment…”

The crisis of Myra coming home with her boss as a houseguest as she’d told Don in a phonecall he wasn’t listening to (or was he?) and catching Don and Ingrid making out cuts right to Don in Miller’s office, post-divorce. Miller reminds him of Myra’s feelings and Don acknowledges their mutual parting of life ambitions (“We both became different people… what each of us wanted, now, outweighed what we once had at the beginning!”). Kirby, scarred for life by memories of war, had no appetite for the ones then said to be going on between the generations and the sexes; Miller, bald, slim, a tabula rasa of pure intellect, is a genderless entity seeking balance — though it’s noticeably the men who are the problem in each of these “cases.”

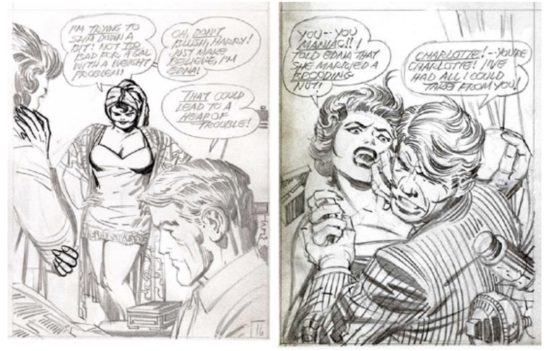

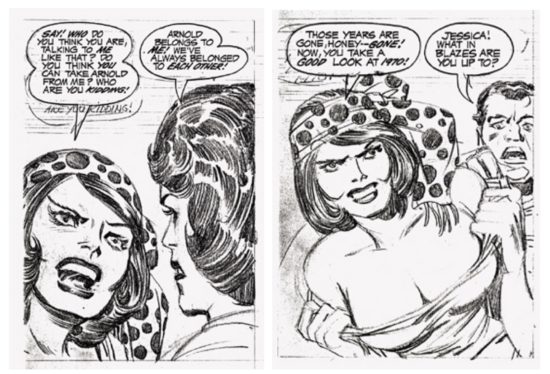

In “The Twin,” suburban husband Harry’s projection of his desires and anxieties onto women, no matter their interior life, is made manifest when his wife Edna’s identical twin Charlotte comes to stay over unannounced. She reminds him of an earlier, adventurous Edna, unnerving him with a material fantasy of the past. He’s jittery as she exercises in the living room with Edna and shows off her new body to her sister (“I’ve been a widow for three years, and it’s time to be a woman again!” — the female sexuality in all these stories is remarkably unashamed, and un-shamed). When he comes home late from “work” one night (once again, at who-knows-what), he walks in on Charlotte making out with a date, and assuming she’s his wife (or does he?), starts beating up on the guy. When Charlotte shows herself capable of decking Harry instead (before Edna gets home and breaks it up), it starts to be clearer why DC’s old guard couldn’t comprehend what they were reading in 1971.

Two more men seek to hold onto youth with more devotion than they show to any actual person, in “The Model” and “The Other Woman.” “The Model” is married to a classic Peter Pan who wants to blow all his money, and hers, on expensive toys and entertainment, while the sickly daughter she wishes to move to the country languishes in their unhealthy city apartment. Christine, working for a fledgling modeling agency, is the only character in all of True-Life Divorce whose occupation we actually know, and her self-centered husband devalues it. Or as Miller tells us in deliciously Ed Wood-ian dialogue, “The future of her marriage and her child hung upon the predictable, irrevocable path taken by a husband on an age-old ego-trip!” Equally fiery language opens the next story: “This case concerns that classic principal in every marital triangle brought to judgement! — She is the one most deeply involved! She is the one who stands alone in the naked light of the arena to face the wrath of moral society! You’ve seen her — but do you know — THE OTHER WOMAN!”

The latter story is the best of the bunch, with a twist premise too good to spoil here. “The Model” was the one that got carved off to be the seed of Soul Love; destiny (and the carelessness of vintage DC editors and greed of collectors) has done this tale the further indignity of leaving one early and two middle pages un-rediscovered, and missing from this volume. But the melodrama is easy enough to follow, and though Kirby’s ear for contemporary Black speech is just as good as he tried to warn his publisher of, the circumstances ring true and the characters’ portrayal is remarkably free of condescension. (Its context among White comic writers of the time, convinced of their relevance and benevolent intentions, brimmed with stereotype, self-consciousness and -congratulation.)

In fact, my biggest surprise in finally reading the full Soul Love was how less jive it reads than I had expected. (The only time I had to hide under my seat alone at my desk was the misidentification of Bessie Smith as “Bessie Jones” in a photo-caption for a historical article added by the current book’s producers.) “Fears of a Go-Go Girl! (Can Come True)” is top-drawer all-that-glitters soap opera (with, again, zero condemnation of the title character’s occupation), colored with suitable psychedelia by Tom Ziuko (Soul Love got closer to publication than True-Life Divorce, so the stories were already inked, mostly by Vince Colletta and one by Tony DeZuniga). DeZuniga’s inks make “Diary of the Disappointed Doll!” look especially lovely, as do Glen Whitmore’s vibrant, modern colors; in this harmless (though again pretty tin-eared) farce about the then-novel phenomenon of “computer dating,” Kirby’s intro-text even veers into a brief seizure of what seems like proto-rap: “Cupid plays it CUTE when he decides to REFUTE what the computer COMPUTES!”

“Dedicated Nurse,” about a caregiver who falls in love with an elderly patient’s son and fruitlessly implores him to go back to the law studies he abandoned to look after the old man’s health, has a horrid leitmotif of fat-shaming at the nurse’s expense (Kirby was clearly not clued into the standards of body-type and beauty outside the you-can-never-be-too-thin-and-white world). Though at the end we get a bizarre and almost-heartwarming look into Kirby’s code of cross-gender fairness: Nurse Aleda, broken-up with her beau Slater and rotated off of his dad’s ward for two months, has dropped half her weight to show Slater that change is possible and he can leave his day-laborer job for law school. Back in Aleda’s arms, Slater exclaims: “You went into the sweatbox for ME! You starved yourself for ME! What could I do for YOU, except to love you and just let you run my life!”

A maybe more well-adjusted pact closes out “Old Fires,” in which two long-ago lovers wonder if they can pick up where they left each other years before. Regrets and recriminations fly between Cleve and Clara in a secluded nature setting made for romance, until they leave with their issues unresolved and Cleve saying, “Come on! This place wasn’t made for fighting or talking! But if we can make it beyond that — we’ll be back!” A closing caption from Kirby, who endearingly signs the last panel, tells us, “It could happen, good friends! It could happen to any couple that takes their leave — holding hands!!” Open-ended and real, Kirby’s basic ethic of equal footing, between man and woman, Black and White, human and human, may save Cleve and Clara’s love — and almost saves even Soul Love.

Giving him help, John Morrow’s brilliant page design, period-perfect logo and convincing production values and replica ads and articles elevate the enterprise and illuminate what could have come of it. “The Teacher,” by far the lamest story in the entire book, is wisely left outside this fine facsimile edition in its drawing-board form to display, among other incriminating artifacts, the grotesque whiting-out and redrawing of almost every face’s features.

At the end of “The Model” Geoffrey Miller had admonished us, “It is the children who are the pawns in this emotional chess game — they feel the slings and arrows and bear the unwarranted scars!” Childhood trauma was a preoccupation of Kirby’s, and to round out his dramas of self-help and social-service in this volume, The Dingbats #2 starts by saying of its stars, “Each of them has a story to tell about the strange and sinister things that can happen to the young.”

These were Good Looks, Krunch, Non-Fat and Bananas, four “forgotten and unwanted” lost-boys whose respective real-life superpowers were handsomeness, muscles, anorexia and insanity. The series’ one published issue had been a more madcap actioner, but bad memories start surfacing in the second and third, with Good Looks confronting the mob enforcer who killed his parents over a debt (and doesn’t know the boy survived), and Krunch being kidnapped back by the legal guardian whose dungeon he fled and who wants to finish driving him mad so he can claim the rest of an inheritance Krunch doesn’t even want. There are some grim, grand panoramas of the kids’ “Danger Street” locale (of which the book provides gorgeous foldouts), and the crowds and situations seem to have converged into the urban landscape from as far back as Dickens’ London to as then-recent as Kirby’s Lower East Side and as far ahead as struggling 2000s Detroit; by its 1975 publication the Dingbats’ world was both antiquated and eternal. Kirby was superimposing his own formative hardship on the present day; whatever was behind him in time was right with him in his mind — not for nothing is the Dingbats’ town called “Inner City.”

Some times, trials, hopes and testaments make a mark so indelible they can never truly be gone. Once in a fortunate while a compendium like Dingbat Love helps make sure that they also can’t be lost.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE