10 Best Adventures of 1985

By:

February 3, 2020

Thirty-five years ago, the following 10 adventures from the Eighties (1984–1993) were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- Margaret Atwood‘s sci-fi adventure The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). In the not-too-distant future, perhaps 20 years from the time of the book’s writing, the United States has suffered a coup transforming an erstwhile liberal democracy into a theocratic dictatorship. Because the American population is shrinking due to a toxic environment and man-made viruses, the ability to have viable babies is at a premium. A puritanical Republic of Gilead, whose capital is Cambridge, Mass., has been established — and the regime’s elite have fertile females assigned to them as Old Testament-style “handmaids.” Drawing on historical atrocities from sumptuary laws, book burnings, the child-stealing of the Argentine generals, and the history of American polygamy, Atwood depicts a dystopia in which social control is perpetuated not only by violence but through everything from clothing to language. “Offred,” the central character, whose journal we are reading, used to be named something else; now she is “of” (belongs to) Fred, a former market researcher who has become one of the architects of the new republic; Fred’s wife, a former televangelist, is presumed barren — and bitterly resents Offred, while yearning for Offred’s child. Offred and some of her fellow handmaids attempt to reclaim their lost individualism and independence; some of this experimentalist novel’s sections describe the lives of handmaids who may or may not be Offred. Interspersed with these snapshots are Offred’s memories of her life from before and during the beginning of the revolution, including her indoctrination at the hands of government “Aunts.” The ending is ambiguous — will Offred escape? Will anyone? Fun facts: Gilead’s Secret Service is headquartered in Harvard’s Widener Library, where Atwood once researched the Salem witchcraft trials. The Handmaid’s Tale won the first Arthur C. Clarke Award; it has been adapted into a 1990 film, a graphic novel, and a much-discussed 2017–present TV show created by Bruce Miller. Atwood has announced a sequel, The Testaments, which appeared in 2019.

- Orson Scott Card’s sci-fi adventure Ender’s Game (1985). I found this book troubling, when I first read it — and that’s before I learned that the author is a right-wing homophobe. But it’s so influential that I must include it in this series! Card’s premise, that children playing videogames and laser tag in an orbiting battle school are training to fight alien invaders, seems designed to appeal to gamers whose grasp on reality is already a tenuous one. And the depiction of the protagonist, Ender Wiggin, as a genius warrior-child who has had the empathy trained out of him by adults looking for a savior is also disturbing: If you enjoy reading about kids who hospitalize and kill other kids, then this is the book for you. There’s also a sexist suggestion that females are inherently too empathetic to become true warriors; however, there are strong female characters. All of this having been said, it is thrilling to watch Ender master the tactics of his school’s antigravity war games — although it feels at times, like you’re watching somebody else play a videogame. There’s a subplot about Ender’s sister and brother, whose online screeds become incredibly influential: Again, one gets the sense that the author is pandering to Internet trolls with delusions of grandeur. The final chapter is, however, exciting — even moving. If you like Starship Troopers and The Forever War, then you’ll like this one. But don’t let your kids read it. Fun facts: Based on a 1977 story published in Analog, Ender’s Game won the Nebula and the Hugo; and its sequel, Speaker for the Dead, did as well. The novel has sold millions of copies, been translated into 25+ languages, and was voted onto both The Modern Library’s “100 Best Novels: The Reader’s List” and the American Library Association’s “100 Best Books for Teens” list. A film adaptation starring Asa Butterfield was released in 2013.

- Bruce Sterling‘s Shaper/Mechanist sci-fi adventure Schismatrix (1985). Humankind — now dwelling in off-world colonies, around the Solar System, far from their ruined home planet — has divided into two warring schisms. Shapers evolve themselves via genetic modification and mental training, Mechanists through cyborgian upgrades; together, these factions make up the Schismatrix: extraterrestrial humanity. Our protagonist, Abelard Lindsay, is an aristocratic Mechanist who has received Shaper training; seeking to preserve Earth-bound human culture, he and his friends lead a rebellion against the Mechanists. Lindsay is exiled to a lunar colony populated by criminals, dissidents, nomads, and “wireheads” who ignore or abandon their physical bodies in favor of virtual reality; this is the most cyberpunk part of the story, which otherwise is a Foundation-like, semi-psychedelic space opera taking place over the course of nearly two centuries. When an assassin comes after Lindsay, sent by a former insurgent comrade, he is rescued by Mechanist pirates. There is much more to the plot: espionage, murder, sabotage, not to mention the arrival of the “Investors,” an alien race who are only interested in making a profit off of humankind. There is also a Robinsonade plot — of the Unalienated Work variety — in which Lindsay works for decades to develop the richest and most powerful state in the solar system. And much more — for better and worse this is a sprawling, Asimovian novel of ideas. Many ideas! Fun facts: Sterling wrote five Shaper/Mechanist stories before this novel; together, they were collected in a 1996 edition entitled Schismatrix Plus.

- Larry McMurtry’s Western adventure Lonesome Dove. A revisionist Western that has been received, by critics and the American public alike, as “the great cowboy novel” — an idealization of the Old West. In the late 1870s, two retired Texas Rangers, Captain Woodrow F. Call and Captain Augustus “Gus” McCrae, decide to abandon the small Texas border town of Lonesome Dove and drive their herd of cattle to the wilds of Montana. Accompanied by Deets, an African American tracker and scout, Pea Eye, a former Ranger, Bolivar, a retired Mexican bandit, and the teenaged Newt, the crusty Call and philosophical Gus head north. They’re trailed by Jake Spoon (another former Ranger, who is wanted for murder) and the prostitute Lorena Wood; Jake, meanwhile, is being trailed by July Johnson, a sheriff from Arkansas, and his stepson; and Johnson is followed by Roscoe Brown, his inept deputy sheriff, and Janey — a girl who takes Roscoe under her wing. It’s a saga! There are sordid, thrilling, horrific encounters with: an Indian bandit named Blue Duck, and his gang; the murderous Suggs brothers; and Blood Indians. Characters drop like flies. Themes of old age, death, unrequited love, and friendship are explored — however, as in all the best sagas, there are no happy endings. The writing is rich, intelligent, entertaining, sorrowful — never sentimental. Fun facts: McMurtry and Peter Bogdanovich (whose 1971 movie The Last Picture Show was based on McMurtry’s novel) developed a screenplay for a Western written for John Wayne, James Stewart, and Henry Fonda. The movie was never made, so McMurtry reworked the script into Lonesome Dove, which won the Pulitzer Prize. It was adapted as a 1989 TV miniseries starring Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones as Gus and Call, as well as Rick Schroder, Danny Glover, Robert Urich, Diane Lane, Chris Cooper, and Anjelica Huston. The sequel is Streets of Laredo (1993); there are also two prequels.

- Gavin Lyall’s political thriller The Crocus List (1985). In his third outing, Major Harry Maxim — a former SAS man skilled in covert reconnaissance, counter-terrorism, and direct action — is assigned to head up a security detail at Westminster Abbey for a royal funeral. When an assassin fires on the visiting US president, killing a low-ranking British government minister instead, Maxim is the only witness as the man falls on a grenade. The gun, the grenade, papers found on the dead man’d person point to the KGB; but, since Britain is about to hold unilateral talks with the Russians over Berlin, why would Moscow order such a hit? Maxim and his friend and mentor at Defence, George Harbinger, investigate. The trail leads to: an ex-WWII British Intelligence officer, now retired in Gloucestershire, who is killed; adilapidated boatyard on the Thames; the British consulate in Washington, DC; a small town in the American midwest; and finally to Berlin. MI5 liaison officer Agnes Algar, whom we met in The Secret Servant (1980) and The Conduct of Major Maxim (1982), proves an invaluable ally in the escapade. Who is attempting to sabotage the prospects of peace in Europe — the KGB? the CIA? Or a clandestine group closer to home? Fun facts: If I haven’t included any of Lyall’s popular aviation thrillers, e.g., The Wrong Side of the Sky (1961), The Most Dangerous Game (1963), and Judas Country (1975), or his international crime thrillers, e.g., Midnight Plus One (1965), Venus With Pistol (1969), on my Best Adventures lists, before now, it’s not because I don’t enjoy them — I do! Alas, they’ve been crowded out by thrillers from the likes of John Le Carré, Len Deighton, Lionel Davidson, Victor Canning, Francis Clifford, Anthony Price, Adam Hall, Joseph Hone, et al. The BBC filmed The Secret Servant in 1984, with Charles Dance as Maxim.

- Greg Bear’s sci-fi adventure Blood Music (1985). Transhumanism — the premise that humankind can/will evolve beyond our current physical and mental limitations — had previously been explored by sci-fi authors such as S. Fowler Wright (The Amphibians), Olaf Stapledon (Odd John), and Arthur C. Clarke (Childhood’s End); Bear was among the first to explore — in the 1983 story that was developed into this novel — the role of “wet” nanotechnology in accelerating our evolution. Ordered to destroy the “noocytes” (simple biological computers) that he’s created from his own lymphocytes, the biotechnologist Vergil Ulam instead injects them into his own bloodstream. Inside his body, the noocytes become self-aware, alter their own genetic material, form a nanoscale civilization… and begin to transform their host. What begins as a kind of horror story along the lines of David Cronenberg’s The Fly (which appeared the following year) rapidly turns into a post-apocalyptic dreamscape, as all life in the North American biosphere is infected and assimilated. There’s an amazing chapter in which a news reporter flying over America reports on the surreal scene; it’s worth noting that Bear began as a sci-fi artist. As if all of this weren’t enough, Bear trots out a pet theory that the nature of reality is affected by its observers… so the sudden introduction of billions of new intelligences throws reality out of whack. Fun facts: Originally published as a novelette in 1983 in Analog Science Fact & Fiction, winning the Nebula and Hugo Awards.

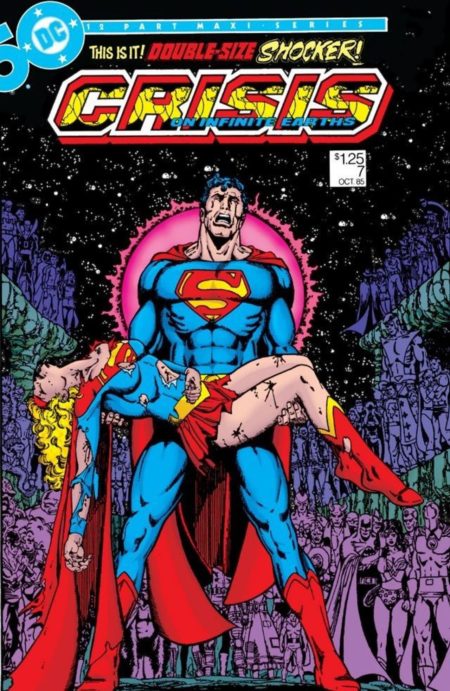

- Marv Wolfman and George Pérez’s Crisis on Infinite Earths (DC Comics, serialized 1985–1986). Since 1963, DC has frequently used the word “Crisis” to describe important crossovers within its Multiverse — that is to say, within the unwieldy agglomeration of “Earths” spawned by writers who, over the course of half a century at that point, had made only cursory attempts to align their story-lines. After two years of research, writer Marv Wolfman and artist George Pérez, whose 1980 New Teen Titans series was a hit, produced a 12-issue limited series with the ambitious goal of unifying DC’s universe. The series — which concerns the destruction of the Multiverse’s many Earths, by the Anti-Monitor, as well as Brainiac’s efforts to conquer the remaining Earths — is infamous for its death count. Wolfman killed off DC icons Kara Zor-El (the original Supergirl), Barry Allen (the Flash of the Silver Age), and many other heroes and villains. There is time travel; there is a portal between the positive and antimatter universes; Superman and Darkseid team up. The series concludes with the creation of a single, unified Earth. DC’s history would henceforth be divided into “Pre-Crisis” and “Post-Crisis.” Fun facts: Followed by the stories Infinite Crisis (2005–2006) and Final Crisis (2008–2009), Crisis on Infinite Earths popularized the idea of a large-scale comic book crossover. The DC Universe has never been the same.

- Philip K. Dick‘s sci-fi adventure Radio Free Albemuth (1985). Unlike Dick’s many stories set in a dystopian future, this one is set in a dystopian present — one in which an opportunistic incompetent, the mouthpiece for a crackpot conspiracy theory and front-man of a right-wing populist movement, becomes president of the United States with the secret support of the KGB and the FBI. (“Why should disparate groups such as the Soviet Union and the U.S. intelligence community back the same man? … They both like figureheads who are corrupt. So they can govern from behind.”) As he wages war against “Aramchek,” an imaginary subversive organization, President Fremont abrogates American civil liberties; this leads to the emergence of a resistance movement… organized through transmissions from a superintelligent, extraterrestrial being or network known as VALIS. (See Dick’s 1981 novel VALIS.) Nicholas Brady, a record store employee, is the recipient of these transmissions, and a kind of subliminal organizer of the resistance; his experiences are a lightly fictionalized version of Dick’s own infamous “2–3–74” gnostic freak-out. As Brady becomes a successful record producer (encoding anti-Fremont messages into folk songs), his best friend, science-fiction writer Philip K. Dick, struggles in vain to stay out of the clutches of the right-wing populists. Brady’s ultimate song-message is written by a woman named Aramchek; it is recorded by a band called, yes, Alexander Hamilton. Fun facts: Drafted in 1976, published posthumously despite not being finalized. The novel was adapted by John Alan Simon in 2010; the film stars Jonathan Scarfe as Brady, Shea Whigham as Dick, and Alanis Morissette as Sylvia Aramchek.

- Ursula K. Le Guin‘s sci-fi adventure Always Coming Home (1985). A difficult but rewarding post-apocalyptic text reminiscent of Engine Summer (1979) and Riddley Walker (1980), Le Guin’s Always Coming Home isn’t exactly a novel; instead, it’s the coming-of-age story of a young Kesh woman, Stone Telling, interleaved with a Silmarillion-esque ethnological account of the cultural facts, legends, poetry and song of the Kesh people. The Kesh are a peaceful community who inhabit an isolated island in what used to be California’s Napa Valley; at some point in the distant past, they seceded from the rest of America in order to cultivate a mindful approach to technology use, ecological systems, and everything else. An Internet-like computer system survives whatever catastrophe befell America; so does solar power, California’s Route 29 (“the old straight road”), steam engines, modern medicine, and flotsam and jetsam like styrofoam. As with the social order depicted in the author’s The Dispossessed (1974), Kesh society is an ambiguous utopia: Stone Telling rebels against the culture’s taboo against scientific and technological progress. Although she recognizes the flaws of the patriarchal, hierarchical, militaristic neighboring society in which she spent some years growing up, she is attracted to some aspects of that culture. Fun facts: Le Guin’s parents were noted anthropologists who studied the native peoples of Alta California; this book — early editions of which included a cassette tape of Kesh music — is a tribute to their life’s work. It is also, according to one character,”a mere dream dreamed in a bad time, an Up Yours to the people who ride snowmobiles, make nuclear weapons, and run prison camps by a middle-aged housewife, a critique of civilization possible only to the civilized, an affirmation pretending to be a rejection, a glass of milk for the soul ulcered by acid rain, a piece of pacifist jeanjacquerie, and a cannibal dance among the savages in the ungodly garden of the farthest West.”

- Cormac McCarthy’s western adventure Blood Meridian or the Evening Redness in the West. McCarthy’s first Western — his previous four novels were in the Southern Gothic genre — is an extraordinary piece of writing. A teenager described only as “the kid,” a runaway from Tennessee, winds up in southeastern Texas in the late 1840s. There, our protagonist encounters Judge Holden — a physically massive, highly educated, completely bald socipath who eventually becomes the novel’s antagonist. (This reader is strongly reminded of Marlo Brando’s turn as bounty hunter Robert E. Lee Clayton, in the now-forgotten 1976 Western movie The Missouri Breaks.) The kid joins a party of Army irregulars on a mission to claim Mexican land; their party is wiped out by Comanche warriors. Arrested in Chihuahua, the kid — along with a cellmate named Toadvine — join a scalp-hunting operation, financed by Mexican authorities and led by a violent owlhoot named Glanton. Glanton’s gang is paid by the scalp, so soon enough they begin killing peaceful agrarian Indians, unprotected Mexican villagers, even American soldiers. Judge Holden, a member of Glanton’s gang, becomes a kind of mythic figure — all-knowing, omnicompetent, evil. There are many more killings, and a flight through the Arizona desert during which the kid and a fellow gang member are pursued relentlessly by the judge. Some years later, the kid — now described as “the man” — encounters the judge one final time. Fun facts: Blood Meridian was initially met with a lukewarm reception by critics; but it has since been described as McCarthy’s masterpiece. Harold Bloom has compared the book favorably with Moby-Dick; and it has appeared on numerous lists of the best 20th-century American novels.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.