OFF-TOPIC (13)

By:

January 3, 2020

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This month, we open one of vintage sci-fi’s favorite years by recalling one of its most perceptive prophets, with one of his most imaginative interpreters…

Old heroes don’t fade away — they were like that to begin with. A mythic golden age of rockstar gods, Hollywood giants, immortal superbeings and legendary real-world leaders shone out to my generation through the haze of graying newsprint, creased and crumpled photography, scratching popping vinyl and film, and posters ripped and repasted over from before we were born. Psychedelic color-spirals in print ads for record-clubs you couldn’t order from anymore, dogeared comics from older siblings, echoes of political martyrs our parents could only try and tell us about, the inconceivable phantom-land of hand-printed rock posters and molding album-covers. Ziggy Stardust himself struck a defiant stance amid anonymous alleyway garbage, in a photo portrait tinted to look like off-register industrial printing, ancient before it started. And thus eternal. Ziggy’s creator, David Bowie, had earlier sung about mystic tomes found in the future by the young; the remnants left behind by truly advanced humans — prophets, the framers of nations or pioneering artists — make you feel like you are the missing, next piece.

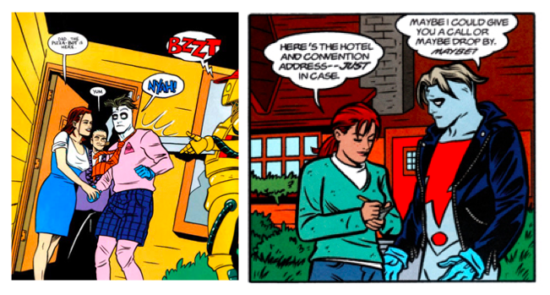

Artist Michael Allred was one of those kids who inherited a slightly-used future and carried it away to form a new world. His signature comic, Madman, rebirthed the groovy heritage of midcentury youth-culture while drawing in influences and sending out ideas that were of-the-minute and always five ahead. His innocent, insightful pop-art progressed through a definitive run on the cosmic divinity Silver Surfer (with Dan Slott), the medium-changing supercelebrity farce X-Statix (created with Peter Milligan), and the cult-famous, seen-on-TV iZombie (created with Chris Roberson). The personas of Bowie in particular hovered like an interplanetary patron saint over all of Allred’s hip, ever-evolving work, and perennially in it, especially the rock-space-opera epic Red Rocket 7, shaped like an old-school vinyl LP and starring a redheaded musician from beyond.

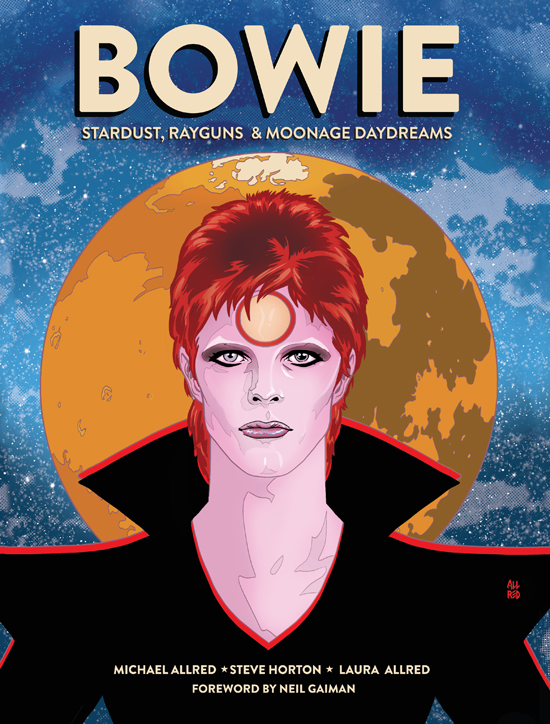

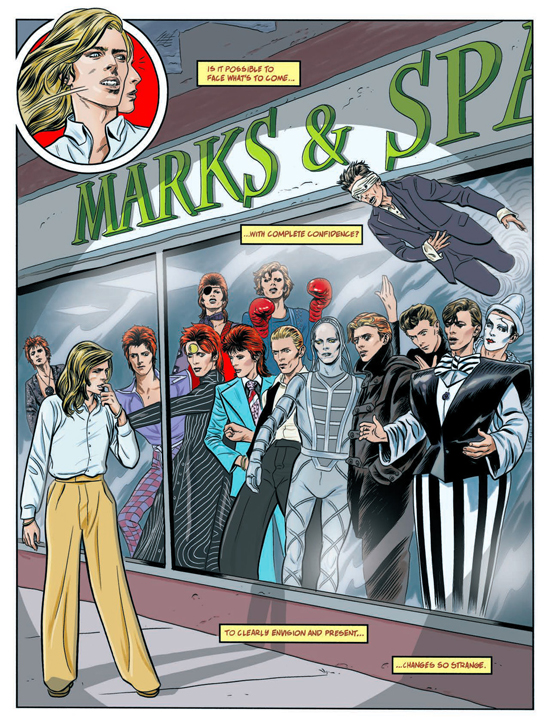

This was one of the ghost-Bowies that have inhabited Allred’s books, and in the graphic biography BOWIE: Stardust, Rayguns & Moonage Daydreams (debuting a day before what would have been his 72nd birthday from Insight Comics), the man fully materializes. Co-written with respected fantasy and sci-fi comics author Steve Horton, drawn by Michael and rendered in larger-than-living color by Laura Allred, the book is a euphoric hallucination of history, a dance into the cartoon-world of rainbow glam and hi-res fantasy. Covering the climb and dive of Bowie’s Ziggy alias, it’s like being jacked directly into, not Bowie’s memories or even legend exactly, but the shared dream — his own and the one he instilled — of what this wild ride would be like. Up to now Allred’s had a starman waiting in the sky, and we sat down to discuss what has happened since he finally came to earth.

HILOBROW: In the book’s “Afterall” you describe the inspired call-and-response by which you and Steve Horton duetted on this book. How much (and what kind of) space was left in his script for your imagery to “tell”?

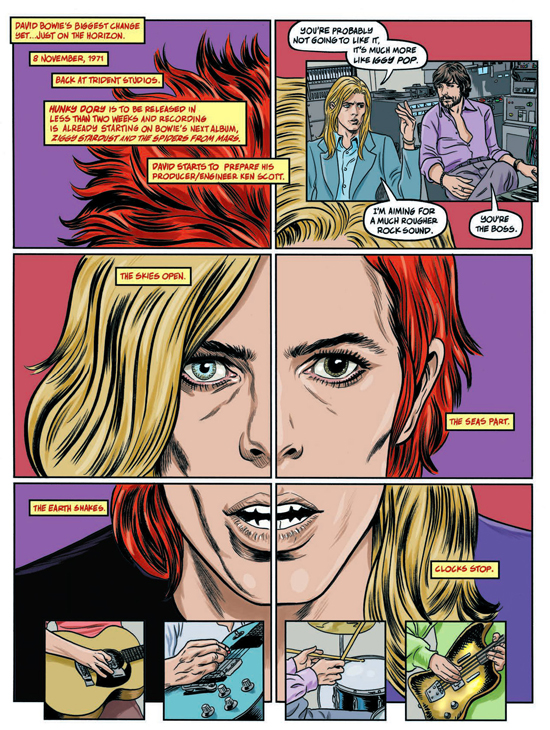

ALLRED: I knew we had around 160 pages to play with, and what Steve presented would have made for several more full-page illustrations. I felt there was so much more that needed to be included in the period, and wanted the book to feel richer, more dense, and as definitive as possible. So I listed additional events and milestones that I wanted added in. Stuff like the girl who gave Bowie the “Ziggy haircut,” Suzi Fussey, and how she ended up marrying his guitarist Mick Ronson. Or how he ended up shaving off his eyebrows, and as many threads of celebrity interconnectivity as possible. I dug up everything I could and then went about cutting off the fat. I needed to find the balance of rich content but also letting it breathe. And then of course musical interpretations, which is the trickiest thing because it can be so personal. In fact, the earliest dispute Steve and I had was how we interpreted a song. The imagery that a song inspires can be so varied. It’s easy to assume we’re seeing the same thing when listening to a song. It’s wild to learn how very different our filters see something. Bowie’s lyrics can be very detailed and specific. Or so you’d think. They are wide open to interpretation.

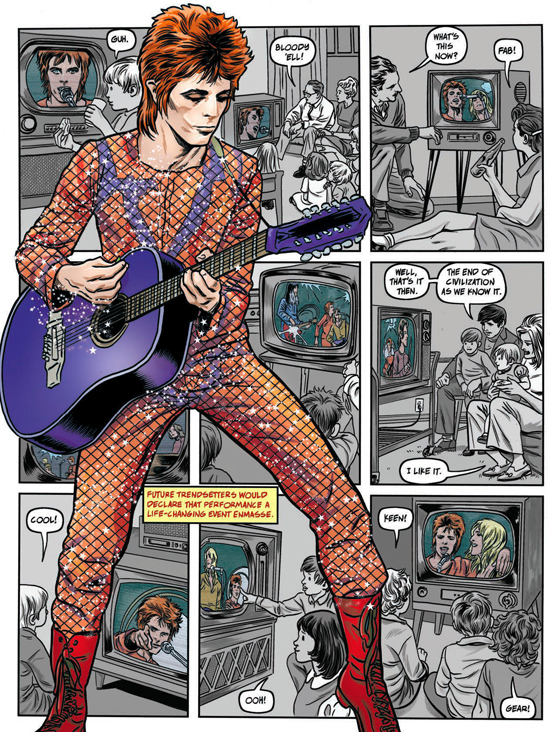

HILOBROW: This is one of the most lush comic experiences I’ve ever had — very much feels like poring over an old-school gatefold record-sleeve full of imagery, only for 160 pages. How do you achieve that luxurious overload from a process of decision-making about each piece of it?

ALLRED: This project is just so very personal for me. My passion for it was unbridled. I very much tapped into that enthusiasm I had as a kid when I spent all my money building my record collection. I’d drink in all those super cool album covers, often copying them, or photos from rock magazines, or just let my imagination run wild and just let my pencil go insane from all the imagery that was rolling through my brain. I knew this was my chance to spill all of that into this beautiful production. Rocket fuel!

HILOBROW: You use a very new style for this story — as if all reality is cast in a filter of those color-hold shadings from ’70s poster-art. (This approach provides a particularly fitting platform for a whole new level of Laura’s modeling of light and color too.) And yet meticulously rendered also — as if this is how life looks within a 1970s poster. What does this say for you, about the vividness of legend and the elusiveness of memory?

ALLRED: Laura and I talked about approach constantly, and the opportunities we had to play and pull and push. After I locked down the final script it all just kind of flew from there. I committed to hand-lettering the pages to pull the layouts together and help give it a hand-crafted structure. By the time I started inking and throwing pages at Laura we were in the zone, and everything after ran on pure energized instinct. I look at it now printed up and I barely remember drawing most of the pages. Laura says it’s like giving birth, almost forgetting the labor, and just holding the baby, drunk with love.

HILOBROW: In a fascinating way you move from homage to re-creation — all the album-covers and other ephemera are note-perfect yet clearly the work of a natural hand. It’s the kind of thing that many artists might just collage in from photographic/reproduction references. Did you feel this was the best way to bring Bowie’s world back to life from the atomic level on up?

ALLRED: Absolutely! I wanted everything documented to have that rush of affection that you’d find in a fanzine, but with my accumulated professional skills and experience “turned up to eleven.”

HILOBROW: The way to depict music in the visual artfom of comics has been wrestled with in many different ways. You use a technique I don’t think I’ve ever seen, the pictorial montage of scenes suggested by a song rather than necessarily including any of its words (let alone sound, which is less possible). You’ve created comics on musical themes many times; how did this mode of expressing it come about?

ALLRED: It was important to us to let it be open to discovery. The images need to stand on their own and be interesting to look at, but at the same time, be recognizable. I’ve already heard from folks who are going to discover Bowie for the first time through this book beyond a peripheral accidental knowledge. I hope this will take them on a thrilling journey of discovery with my imagery filling in the blanks when they take that deep dive. But more likely the experience will be fans who will recognize the references. Maybe sometimes too obvious and on-the-head, like showing Bowie literally kissing a viper’s fang. Fortunately, I’ve been doing this enough, most of my life as a crazed fan, and professionally, like in Red Rocket 7, to have a pretty good understanding of what works and maybe more importantly, what doesn’t work.

HILOBROW: There are only hints of “backstage musical,” with the Spiders’ growing discontent and Bowie’s less-than-perfect management style. It only pokes through the surface occasionally. We see even less of Bowie’s thinking on this, though then there’s that remarkable part where you isolate his singing of the word “sorrow” in a single panel during the serial death of the Spiders in a handful of one-off concerts and TV shows. Did you and Horton want Bowie’s interior to be something we have to look for?

ALLRED: Speaking for myself, I did. If someone wants to dig for ugly, they are welcome to it. You can come at it from the anger of drummer Mick “Woody” Woodmansey, or the complete avoidance and isolation of David Bowie, who was being placed in a bubble of ignorance, which he may have been fine and comfortable staying in. And he eventually paid for it mightily himself. But that’s the sequel. Ultimately, for me, this is a ridiculously elaborate love letter, not a hit job. But at the same time, some things cannot be avoided, and I think we struck the right balance for each reader to put the pieces together and choose different perspectives.

HILOBROW: In general, the book seems to follow an arc from the mind of Bowie to his surface –—the song-montages feel like the raw material of his thoughts, but as of the Ziggy era these mostly evaporate as we’re caught up in the external whirl of his concerts and exploits and costumes and guises. Did you and Horton mean to trace a kind of closing-in of Bowie the person? (I guess we do see his future self breaking through those walls at times…)

ALLRED: That’s the whole driving force, right? The surface personas, the trademark changes, are the only constant thread through his career, right? We see the “real man” in the first chunk of the book take shot after shot after shot after shot at stardom, at any kind of success. We see his influences as puzzle pieces, and he puts all the pieces together through his mixer. Alice Cooper was a huge breakthrough for him in creating an alter ego for the stage. And like all of Bowie’s influences he amped everything up. When superstardom finally hits he consumes it in full, and we present it as a series of thrilling rapid-fire images. He quickly discovered that he could maintain a personal mystique by creating facades for the public, and be more interesting than David Jones, the real man.

HILOBROW: I love the signaling of character through style — like the way Tony Defries’ face is always the same rubber-stamp-like mask. Almost like a visual equivalent of how grownups’ voices sound in Peanuts TV specials. Does the repertoire of graphic possibility give you the tools to tell a story like this most fully?

ALLRED: It does. There are so many tricks you can collect in your bag over the years. Shortcuts to storytelling clarity. My presentation of Tony Defries suggests he has a mask of his own. A dull, predictable, shallow mask of deception. You think you know what you’re getting with the one face, but his agenda is his own, and it’s hidden behind that mask of reliability.

HILOBROW: There is no account of Bowie’s life that has as few explicit, or even passing, references to his non-normative sexuality as this book. In the period it covers, male lovers including Lindsay Kemp and Ken Pitt are a matter of record or at least reasonable surmise. On the other hand, of course Bowie’s flamboyance and androgyny are on full display — even fuller than in real life sometimes; I love that you have David be the mum in illustrating “Life on Mars?”. In fairness he changed his story several times over the decades (which you do depict), and the LGBTQ community has gone back and forth about how much to claim him and how much he truly embraced them… and as in all your work, the male face and form are presented at least as joyously, erotically and idealized as the female. What was the thinking on how to address or incorporate queerness into this telling?

ALLRED: I wanted it to be as matter of fact as possible. Given the time, the early 1970s, it was incredibly ballsy to make the statement he was making. Even cynically, or exploitively, it was potentially a very dangerous thing to do. Certainly there was no model of success to follow. A seemingly happily married man with a child casually claiming to be gay was an astonishingly bold statement to make. Even today it would spin heads around. Though today, arguably, more accepted by the masses. That it created a sensation of confusion may be the controversy. That it was a lie or thrown out with the intention of creating headlines would certainly be upsetting to people who try to live an honest lifestyle without the perceived protection of wealth and celebrity. But David had yet to solidly acquire either. It could easily have been the final nail in the coffin of his career.

From my perspective, it drew a line in the sand that I fought, literally, to cross. When I discovered Bowie and became completely intoxicated with his music and the idea of a Rock Star from outer space, I was completed surrounded by dolts who would have you believe that being gay was the worst thing you could possibly be and should have the crap kicked out of you if you were. Choose your insult, but any gay slur thrown at you was an instant fighting word. Throw down and start swinging or you were what you were being called.

Being told he was gay was supposed to make me give him up. Not gonna happen. I was a massive Bowie fan, gay or not. So, at twelve, I learned about homophobia, and the seeds of tolerance were planted. If he was in fact a homosexual, or bisexual, or cosmicallysexual, it was A-okay with me. I didn’t and still don’t care. He carved out his happy place. Good for him! I even had to ask myself if finding him fascinating and drawn to his imagery made me a homosexual. A powerful thing to be confident in your sexuality. To acknowledge that beauty and/or attraction can be found in anyone.

I found my perfect partner no question. I see a beauty inside Laura that will never fade. An ageless attraction. And I’d wish that for anyone, no matter their sex.

Now I haven’t had to struggle the way folks in the LGBTQ community may have, so I’ve no right to say whether they should embrace or claim Bowie as a groundbreaker of acceptance. But again, from my perspective, he inspired me to want anyone and everyone to be who they want to be and be with who they want to be with. I’d like to think I’m a better person because of that kind of thought-provoking inspiration.

HILOBROW: Has there been any response from Bowie’s family, or any of the other people portrayed here?

ALLRED: Honestly, the most heartbreaking criticism I could imagine from this project would be harsh criticism coming from David Bowie’s family, so I’ve not for a second entertained presenting it to them out of pure fear of rejection. But just last week a troll on twitter threw a “twitter rock” at an artist friend who was lovingly praising the book. And Neil Gaiman, who I know is friendly with David’s son, Duncan Jones, stepped up in defense with the glorious statement, “The Bowie Estate love it. It’s made by craftspeople who are all Bowie fans.” Meant the world.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE