10 Best Adventures of 1979

By:

December 15, 2019

Forty years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Nineteen-Seventies (1974–1983) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

I’m dedicating this post to Tom Nealon, whose enthusiasm for several of these adventures is palpable. In the years since we met, he has inspired me to revisit Adams, Sorrentino, and Calvino; and it was he who first introduced me to the writings of Octavia E. Butler. Alas, he associates the film adaptation of The Neverending Story with his parents’ divorce. (Sorry, Tom.)

- Douglas Adams’s absurdist science fiction adventure The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. When a Vogon constructor fleet arrives to destroy Earth (in order to make way for an intergalactic bypass), Arthur Dent, an ordinary Englishman, is rescued just in time by Ford Prefect — a human-like alien writer for the eccentric, electronic travel guide The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Clad only in his pajamas and dressing gown, Arthur stumbles into a grand misadventure. He and Ford wind up traveling in the Heart of Gold, a spacecraft equipped with the experimental Infinite Improbability Drive, along with Ford’s cousin, the two-headed President of the Galaxy Zaphod Beeblebrox; Marvin, the Paranoid Android; and Trillian, an Earthling formerly known as Tricia McMillan. It seems that Earth is (was) an organic supercomputer, created by another supercomputer, Deep Thought — which was created in order to calculate the “Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything.” (The number 42, which mathematician and fatasy writer Lewis Carroll seemed to find particularly funny, is — according to Deep Thought’s non-organic calculations — the Question’s answer.) Arthur becomes the target of the descendants of the Deep Thought creators, who believe his mind must hold the Question. Along the way, we meet excellent characters like Slartibartfast, the planetary coastline designer responsible for the fjords of Norway…. Fun facts: The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was a 1978 BBC Radio 4 broadcast; the novel was adapted from the first four episodes. The story was adapted for TV’s BBC Two in 1981, and as a 2005 movie starring Martin Freeman as Arthur, Mos Def as Ford, Sam Rockwell as Zaphod, and Zooey Deschanel as Trillian. Sequels include The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (1980), Life, the Universe and Everything (1982), and So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish (1984).

- Octavia E. Butler‘s New Wave sci-fi adventure Kindred. In this realistic (visceral, even) sci-fi/fantasy hybrid yarn, which Butler modeled on grim North American slave narratives by the likes of Harriet Tubman, Dana, a young, educated African-American woman in contemporary Los Angeles, finds herself shunted back in time to an antebellum Maryland plantation. (Unless she’s just hallucinating?) Dana, who is married to a white man in the present, discovers in the past her own ancestors — a white planter and a black freewoman who has been forced into slavery. Her ontogeny — as a black woman fully conscious of slavery’s legacy in contemporary America — recapitulates the phylogeny of her ancestor, who loses her innocence, faces harsh punishment, develops strategies of resistance, and ultimately develops the ability to escape from a repressive, racist white society. Kindred unflinchingly interrogates the intersection of power, gender, and race, but the narrative is far from simple: Dana’s ancestors, Rufus and Alice, were childhood friends, and Dana ends up developing sympathy for Rufus, despite the fact that he grows up to be a monster. She also encounters Sarah, an angry slave who only appears to be a submissive “mammie,” and other characters who fail to conform to previous depictions of slavery, from Gone with the Wind to Roots. The time travel narrative is also complex, as Dana — and, sometimes, her husband — ricochets back and forth from the present to various points in Alice and Rufus’s life stories. Fun facts: Kindred was a bestseller, and remains popular today; it is often chosen as a text for community-wide reading programs and high school and college courses. It was adapted as a 2017 graphic novel by Damian Duffy and John Jennings.

- John le Carré’s espionage adventure Smiley’s People. At the end of The Honourable Schoolboy (1977), the second installment in the so-called Karla Trilogy, spymaster George Smiley is forced out of the Circus — the British intelligence service to which he’d returned (see 1974’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy), in order to root out a mole — and into premature retirement. Here, he’s lured back into action when he learns that Karla, the Soviet Intelligence mastermind who’d planted the Circus mole, may have a secret weakness that can be exploited. Like Call for the Dead (1961), in which we first meet Smiley, this story begins with a murder investigation: Why did Karla have General Vladimir, one of Smiley’s contacts during the war, killed in London? The investigation leads Smiley’s people to Paris, Germany, Switzerland… and it takes Smiley back to Berlin, in the end. In order to capture Karla, Smiley will have to allow himself to be possessed by the very evil he has fought against; he must be utterly ruthless, remorseless. “Hunter, recluse, lover, solitary man in search of completion, shrewd player of the Great Game, avenger, doubter in search of reassurance,” Le Carré writes of his protagonist, “Smiley was by turns each one of them, and sometimes more than one.” Connie Sachs, Toby Esterhase, Peter Guillam, all play a role: Those of us who enjoy getting-the-gang-back-together adventures will recognize this slow-moving, but gripping story as falling into that category. Fun facts: The General Vladimir character was partly modeled on Colonel Alfons Rebane, an Estonian émigré who led the Estonian portion of SIS’s Operation Jungle in the 1950s. Smiley’s People was dramatized as a very good six-part TV miniseries for the BBC in 1982, starring Alec Guinness as Smiley.

- Michael Ende’s epic fantasy The Neverending Story (trans. 1983, Ralph Manheim). While escaping from bullies, the overweight and neglected Bastian hides out in an antiquarian book store… where he stumbles upon a book titled The Neverending Story. Reading it, he learns of Fantastica, an Oz-like land ruled by the benevolent, but dying Childlike Empress… and threatened by a formless entity known as “the Nothing.” To make an (epically) long story short, a boy warrior named Atreyu and Falkor, a “luckdragon,” seek a human child who will save the Empress by bestowing upon her a new name; the two encounter every manner of monster and marvel, and begin to apprehend Fantastica’s indirect relationship with the human world. (Fantasticans who voluntarily leap into the Nothing, for example, become human lies.) Bastian is brought to the Empress, but he cannot bring himself to believe that he is the human child described in The Neverending Story… so the Old Man of Wandering Mountain reads aloud from The Neverending Story, demonstrating that Bastian is now one of its characters. The Empress is saved… but this, we discover, is only the first stage of Bastian’s adventures in Fantastica! It’s a trilogy, or a quadrilogy, compressed into a single volume. Fun facts: Wolfgang Petersen’s 1984 adaptation of the novel’s first half starred Barret Oliver as Bastian, Noah Hathaway as Atreyu, and Tami Stronach as the Childlike Empress; Ende was unhappy with the adaptation. The title song, composed by Giorgio Moroder, became a chart success for Limahl, the former singer of Kajagoogoo; Dustin and his girlfriend cover the song in a metafictional moment during the third Stranger Things season. There were two sequels to the movie, one released in 1990, and another in 1994.

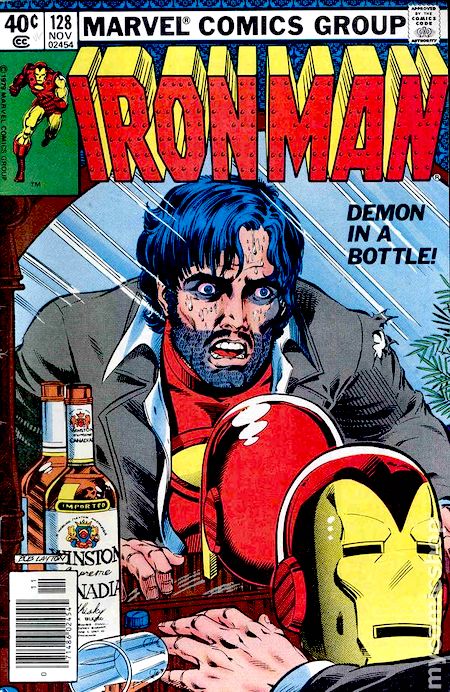

- The IRON MAN story “Demon in a Bottle” (serialized March–November 1979). The nine-issue story arc of Iron Man #120-128, plotted by David Michelinie and Bob Layton, with script by Michelinie, introduced readers to the armor-clad superhero’s most insidious foe yet: his own alcoholism. Illustrated by John Romita, Jr. and Bob Layton, with an assist on one issue from Carmine Infantino, “Demon in a Bottle” begins with the usual sort of action: Prince Namor hurls a tank through the air, which clips a passenger jet carrying Tony Stark — who dons his Iron Man suit and saves the day. He confronts, then teams up with Namor — once he discovers that Namor is defending an island’s inhabitants against an oil company. Stark’s Iron Man suit begins to malfunction, mysteriously; he ends up accidentally killing a foreign ambassador, and is forced to step down as the Avengers’ leader. It turns out that Justin Hammer — an evil version of Stark, who makes his first appearance here — is the saboteur, but that’s almost beside the point. Stark’s drinking is out of control! He’s confronted by his girlfriend, the badass Bethany Cabe (later, head of security for Stark Enterprises), who offers him some much-needed emotional support. With Bethany’s encouragement, Stark gains the confidence to overcome his drinking problem, maintain control of his company, and return to action. Fun facts: “Demon in a Bottle” has been recognized by critics as “the quintessential Iron Man story,” and “one of the best superhero sagas of the 1970s.” “Demon in a Bottle” was originally the title of the story’s final issue; when the story was first collected in paperback form, it was instead titled “The Power of Iron Man.”

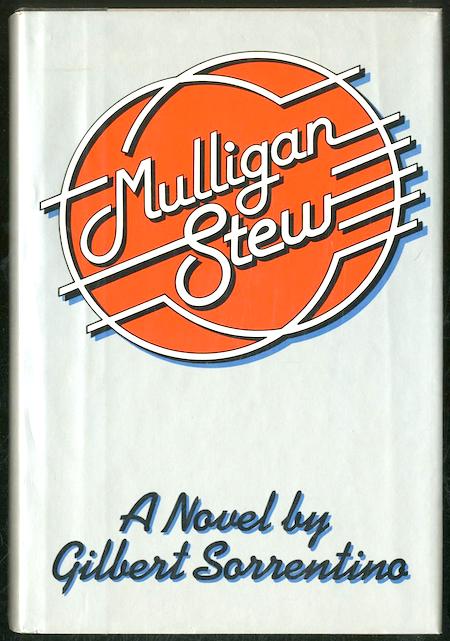

- Gilbert Sorrentino’s meta-fictional adventure Mulligan Stew. In Flann O’Brien’s 1939 metafictional masterpiece At Swim-Two-Birds, Antony Lamont is a character invented by Dermot Trellis, a cynical writer of Westerns and himself a character invented by O’Brien’s unnamed protagonist; Lamont and some of Trellis’s other characters become resentful of his godlike authority over their lives, and work to subvert his control. Here, Lamont reappears as the pompous, self-deluded, Sorrentino-esque author of Three Deuces, an avant-garde but poorly written crime novel. Struggling to write a new-wave murder mystery, currently titled Guinea Red, Lamont doesn’t at first comprehend that his own characters — whom he’s borrowed from F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, and Dashiell Hammett — have lives of their own. They’re not fans of the roles they’ve been forced to play; they’re particularly unhappy with being forced to mouth and enact unspeakable clichés. Sorrentino’s MS is a brilliant, witty, weird farrago; it helps to know something about the authors being referenced, not to mention the New York literary scene of the 1960s–1970s. Yes, it can be bewildering to navigate the journal entries, love letters, interviews, erotic poetry (for Lamont to review), parodies, advertisements, academic journal writing, and interminable lists, but stick around for the intentionally, hilariously poor writing. Is it an adventure? Not exactly — though it’s about reading and writing adventures, which is close enough for me. Fun facts: The Joycean literary critic Hugh Kenner wrote, of Mulligan Stew, “for another such virtuoso of the List you’d have to resurrect Joyce.” The book’s title is a punning allusion to the character Buck Mulligan in Ulysses. Sorrentino began the novel in late 1971 (it’s very much a product of the Sixties, that is) and finished it in early 1975; after many rejections, he sold the book to Grove Press in 1978.

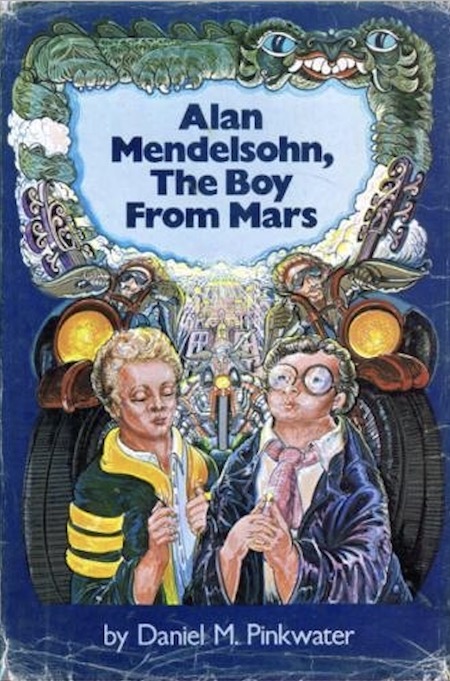

- Daniel Pinkwater’s YA sci-fi/fantasy adventure Alan Mendelsohn, The Boy from Mars. The first Pinkwater novel I ever read, and still my favorite. Leonard Neeble is an awkward, nerdy social outcast at Bat Masterson Junior High; his family has moved from the Bronx to the suburbs, where Leonard is miserable. His psychiatrist is worse than useless, his parents and teachers neglectful. So far, so Judy Blume. Then Alan Mendelsohn shows up. Entirely unconcerned about social status, Alan befriends Leonard — and starts a school-wide quarrel when he claims to be a Martian. Both boys are suspended, during which time they explore funky downtown Hogboro, where the owner of an occult bookstore sells them a bogus kit meant to enable telepathy and psychokinesis. Mirabile dictu, Leonard and Alan develop these powers — which they deploy subversively, back at school. Soon, the two are studying lost civilizations such as Atlantis and Lemuria, along with a copy of Yojimbo’s Japanese-English Dictionary… which helps them increase their newfound powers. An encounter with Yojimbo himself reveals that the true purpose of his Dictionary is to enable travel to Waka-Waka, a parallel Earth/lost continent… whose inhabitants have fallen under the control of invisible extraterrestrials! I enjoy the whole yarn, as silly as it gets — but particularly the boy’s escape from the suburbs, and exploration of Hogboro — with its eccentrics, comic book shop, and Bermuda Triangle Chili Parlor, and overgrown Hergeschleimer’s Oriental Gardens. Pinkwater’s message: Break free, and things will get better. What kind of adventure is this? A survivalist one: about making it through adolescence. Fun facts: Pinkwater sets a number of his stories in Hogboro-like neighborhoods reminiscent of Chicago, where he grew up. Also recommended: Lizard Music (1976), Yobgorgle: Mystery Monster of Lake Ontario (1979), and The Snarkout Boys and the Avocado of Death (1982).

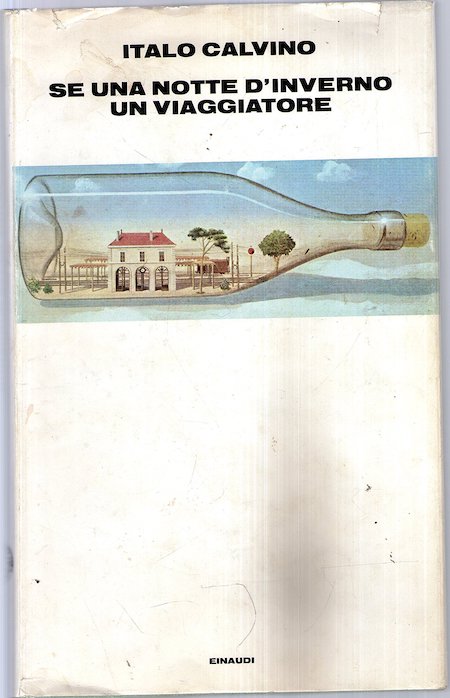

- Italo Calvino‘s postmodernist adventure Se una notte d’inverno un viaggiatore (If on a winter’s night a traveler). A reader — you, the reader — is trying to read a book called If on a winter’s night a traveler, but instead keeps finding himself reading the first chapter of other books… each of which ends on a cliff-hanger of sorts. Each chapter begins by describing the reader’s efforts to read the next chapter; and each ends by recounting the first part of a new book, each time from a completely different genre. He (you) meets a woman, Ludmilla, who’s experiencing the same problem; she has a sister, who has her own ideas about the purpose of reading. There is an adventure, of sorts, here, the telling of which is influenced by the various literary genres encountered: Our protagonists are on the track of an international book-fraud conspiracy; they encounter reclusive novelist Silas Flannery, a translation scammer; there’s a political angle, too. Calvino would later explain that the book’s structure was inspired by linguist and semiotician A.J. Greimas’s “semiotic square,” which explores three types of relationship — contrary, contradiction, implication — between opposed concepts. Fun facts: Published in an English translation (by William Weaver) in 1981. Calvino’s decision to write an experimental book based on Greimas’s semiotic-square model was influenced by his membership in Oulipo.

- J.G. Ballard‘s fantasy adventure The Unlimited Dream Company. “If the doors of perception were cleansed,” declaimed William Blake, in a phrase that would inspire everyone from Aldous Huxley to Jim Morrison, “every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite.” Bidding farewell to the transgressive sci-fi — e.g., Crash (1973), Concrete Island (1974), High Rise (1975) — for which he’d become infamous, here Ballard explores the tenuous, constructed nature of reality and the self. Blake, a failed writer and would-be mercenary, steals a light aircraft… and crashes it into a river by Shepperton, the London suburb where Ballard himself was living. As with all Ballardian catastrophes, the crash liberates our protagonist from repressive British forms and norms; the possibilities of the Shepperton into which Blake staggers are limited only by his own (sociopathic, pornographic, increasingly messianic) imagination. He wanders from hallucinatory scenario to hallucinatory scenario, remaking the world as he goes. He enjoys sexual congress with men, women, flora and fauna; he evolves into a godling equally capable of destruction and creation. The writing is often lyrical, while some of Blake’s fantasies are disturbing or downright sick. Why can’t he escape Shepperton? What are his responsibilities to others? Will he ever reunite with Miriam St. Cloud, the woman he loves? Fun facts: Nominated for the John W. Campbell Memorial Award, The Unlimited Dream Company won the British Science Fiction Association Award. Malcolm Bradbury said, at the time, that it is “heady stuff, a dreamy pastoral, but Mr. Ballard sustains it from a well-funded imagination, a prolix style and a great mythical sense.”

- John Crowley’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Engine Summer. A beautifully written, trippy novella set in a post-apocalyptic America, where relics of the past confound and amaze our protagonist, young Rush That Speaks. He’s grown up in Little Belaire, an idyllic, tribalist community of “true speakers” who fled society’s collapse (specifically, they appear to have fled Bel Air, California) in the distant past. This reader could have happily explored Little Belaire and its traditions along with Rush That Speaks for a longer stretch, but when Once a Day, the girl he loves, absconds to live with a cat-like society called Dr. Boots’s List, Little Rush heads out after her. First, however, he spends time living with Blink, a “saint,” in a treehouse, gathering more intel about the high-tech, unhappy prelapsarian world of the vanished “angels.” Once he’s taken in by Dr. Boots’s List, Rush That Speaks undergoes a mind-meld with Dr. Boots — from which he will never fully recover. At which point, an “angel” drops from the sky, and much is made clear to us. As with Riddley Walker, published the following year, Engine Summer is among other things a riddle, requiring readers to puzzle out secrets of the past (our near-future, perhaps) that the book’s characters themselves will never truly understand. The book’s ending is a deeply poignant one. Fun facts: Crowley is best known as the author of Little, Big (1981), a much-admired fantasy novel, and for his Ægypt series of novels (1987–2007). I like these books, too, but strongly urge science fiction fans to revisit his early work.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.