OFF-TOPIC (12)

By:

December 13, 2019

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This month, we close the year in digression with a mind’s-eyewitness account of two revered and remote artists’ collaborative friendship…

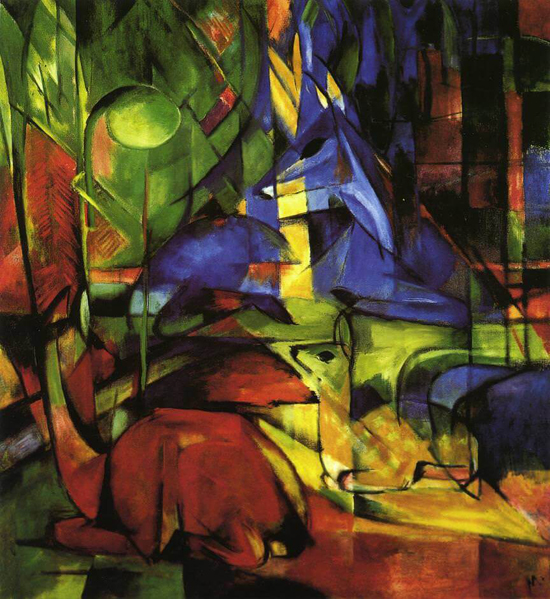

What’s never been seen before was created with no model to work from, and artist/playwright Ran Xia turns her gaze away from the artifacts of existence to the vivid, vibrant void. Her new play In Blue, a conjectural biography built from vestiges of the painter Franz Marc and poet Else Lasker-Schüler’s lives, shows us none of Marc’s canvasses, and centers on Lasker-Schüler’s search for the one that nobody now can see. The Tower of Blue Horses got mounted in the Nazis’ “Degenerate Art” exhibition until military veterans complained that, since Marc had died in WWI, he was a patriot, so it was removed; but since the “curators” thought Marc’s friendship with Lasker-Schüler made him a Jewish sympathizer, the painting disappeared altogether. Xia looks through the empty frame at the friendship the two maintained, echoed in the words of their deep (often epistolary) relationship, Lasker-Schüler’s aching, sublime verse, Marc’s letters from the battlefield, and the fertile, intensely felt spaces between every line.

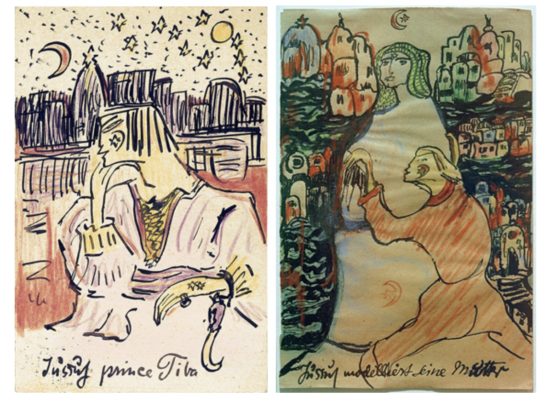

Marc was a painter of subjective, mystical scenes of nature, usually totemic animals in a visionary, psychological palette; carved from the elements, faceted like the rainbow light cast from jewels. Graphic, jagged planes, otherworldly veils of mist, and quantum/cubist segmentation of space were passed on his perceptual journey, which ended at age 36 when shrapnel killed him instantly. Lasker-Schüler was a figure of legend in Expressionist Berlin, acclaimed in her lifetime as the greatest of Germany’s lyric poets, and gifted in visual arts herself, with a wardrobe of public and literary identities, a lifetime of loss and an oeuvre of wrenching insight and cosmic perspective; a single mother and singular independent female presence, she would lose her son to TB and her country to fascism, dying at 75, impoverished and obscure, as an exile in Jerusalem.

Lasker-Schüler and Marc corresponded in-character, she as “Yussuf, Prince of Thebes” and he as “The Blue Rider”; they investigated the mysteries of each other as Xia folds back the layers of time and awareness between our reality and theirs. The private Lasker-Schüler matches her serial loss with an incantatory repetition; when alone, calling for the “five missing horses” in the painting first sent to her as a study on a postcard, it can seem a mad echo; when addressing questions to the Franz of her relived past (or personified contemplation), as in her recurrent question, “Why horses?”, it represents Marc’s unreachable secrets and her unquenchable inquiry — there is a different, valid reason each time, and in lives of limited length this can’t bring contentment.

Finn Kilgore is radiantly contained as the earnest, searching Marc, and Alyssa Simon outsize in life-performance and heartbreaking in personal solitude as Lasker-Schüler; a lone cellist, Luke Santy, provides counterpoint, with somber classical intonations and spectral, processed effects. As much of Xia’s work remains submerged as visible; script directions prime the canvas in swaths of emotion rather than specifics, as when the actors are advised, “FRANZ paints a stroke of blue. It blossoms, like bloodstreams on a sheet of glass. They watch.” — we can guess at the iceberg underneath these characters’ narrow peak of common ground, but we aren’t meant to know everything, or think everything can be known. I got in touch with Xia to talk about the scenes painted and evaporated nightly on her story’s stage.

HILOBROW: Your script and direction take consideration of the visual in ways that are exceptional — that marvelous phrase in the script, “The decorations are austere. It should seem as though there’s something incomplete about this picture,” and the inventive “effects” that are very minimal furnishings, like the string of lightbulbs that Franz screws in to illuminate letters hung behind them, or the roll of iridescent fabric that Else unfurls to transmute into an ocean around her. Design could have overwhelmed drama, and character dynamic could have impoverished the seen environment, but instead it was like watching a kinetic painting (again from the script: “In this play, time is like layers of paint on a canvas: they blend into one another.”). Were you a graphic designer first, and this informed your writing, or have the two gifts always been simultaneous and thus naturally interplayed?

XIA: I dabble in graphic design occasionally (or rather, I have specific tastes in graphics that represent my own work so I usually just end up designing my own posters) but it’s not necessarily an initial career choice. My dad is a painter. Life didn’t work out that way for him but he had initially wanted to go to art school and become a professional artist. He ended up becoming a scenic painter for films and working for decades in the film industry as an editor and writer. Now, ever since his retirement he’s been creating new oil paintings in abundance. He’s marvelous at using pigments to capture light. Growing up I never took serious lessons from him, and spent the entirety of my afterschool/weekend/summer vacations practicing the piano, so I suppose my first identification as an artist would be through music. Still, we’ve always been a museum/gallery family. I remember going to those touring Van Gogh, Dali exhibitions and my father and I would spend hours in those tastefully lit halls while my mom sat on a bench somewhere drinking tea (she now draws illustrations herself as well). In college I was a psychology major with a minor in fine art. I did my thesis on cognitive functioning processes in performance art and created illustrations in the style of stained-glass windows for theatre works I enjoyed during those years. One of my graduation projects was actually an art exhibition of my works. An ink on photo paper interpretation of Franz Marc’s The Tower of Blue Horses was in the exhibition.

I have never been interested in strict realism, as I always crave a bit of magic when it comes to storytelling. I’m glad you noticed the iridescent fabric and the letters lit by lightbulbs. Of course the use of simple sets and props is partially because of a modest budget, but I truly don’t believe theatre should ever need to recreate anything elaborate. I like to put trust in the audience that they’ll see, like I do, an entire ocean in a piece of fabric, and the hope Franz’s letters represent for him during the war. The wire that connects the light bulbs also conveniently provides a path for him so that’s an additional bonus. During rehearsal we also discussed how objects carry memories and letters don’t need to be words. Marc was all about seeing what’s possible, beyond visible, which is a very childlike view of the world. We needed so little to create entire worlds when we were kids, and I really love to embrace that when making theatre.

HILOBROW: At times Else alternates between first-person and third-person pronouns in speaking of herself. This of course in part denotes the “character” she’s showing to the world (and reminds me of how Ringo Starr now always refers to the Beatles as “them” not “we”), but also makes a connection to me of a mindful dissociation I witnessed in my late wife when she was close to leaving this world, an alternation of vantage-point between body and spirit. Is Else trying to see herself and her misfortunes at a merciful distance? Was she memorializing herself before she was gone?

XIA: I think you’ve accurately captured Else’s point of view. I believe it’s a coping mechanism when people use third person to refer to themselves or certain experiences they’ve endured. There’s sort of an innate performative nature when Else does that. It’s a lot easier to insert an objective filter when processing something traumatic.

HILOBROW: Your Franz Marc very much felt to me like the troubled, yet gentle personality my mind assembled from his writings. This, as Else knows well and says often, can be as much a creation as any play or painting. Yet there was a stoic center to your conception (and Finn Kilgore’s portrayal) of him that rings true. (Just as there is a core sadness to your and Alyssa Simon’s Else that makes all her facades feel transparent and trustworthy.) You’ve said this is not a biography — did you feel there was a way, not to tell their whole life story yet in a profound sense, meet them?

XIA: I met Franz early on (through his paintings) and Else halfway through creating this piece. Discovering her knocked the initial idea of this play out and is why this is now a two-hander. We talked a lot about unrequited love during rehearsals and whether or not we should interpret this relationship with elements of romance or not. I’d like to leave that up to each audience member.

There is a core sadness to Else because I finished up this work during a time of upheaval in my life. The sense of not being able to experience security was what I felt during my 11 months of not being able to work, waiting for my O1 visa approval, and surviving on odd gigs, people’s kindness (which can be embarrassing for someone with a lot of pride.)

Franz was sort of Else’s rock before WWI but she’s not the easiest person to hang out around. I still don’t know her very well after spending so much time conversing with her in my head, and I still don’t know if I like her or not as a person. We discovered that she and I are both earth snakes in Chinese zodiacs. Perhaps that makes sense. She’s also extremely hurt by constant loss. It’s actually quite understandable how guarded she became, underneath that brandished facade.

Franz was easy to identify with. I too was a quiet gentle kid with a storm cooking up inside. The rebellion we choose (Franz and myself, and I believe, you!) isn’t lashing out as a teenager, but rather subtle. I first started working with Finn in 2017, on a different project, but around that time was when I picked this piece back up again. Perhaps I wouldn’t have done this production so quickly had I not found the perfect Franz.

HILOBROW: Related to that, the art of historical reclamation always involves a blend of incorporated quotes with words and actions the person “would have” said and did. You seem to have absorbed Lasker-Schuler’s poetic voice very pervasively — “You could hear the opera of light bouncing off pigments,” etc. — how do you yourself start “hearing” and recognizing what words and actions fit the people, and what interactions and incidents fill in parts of the picture that are lost to us?

XIA: In middle school, our music teacher gave us a lesson on impressionism in music (Debussy, etc.). And our assignment was to pair up a painting and a piece of music and explain why. I don’t remember which piece I chose but the assignment stayed with me. My piano teacher was also big on “seeing the music.” She’d ask me to describe the events within a piece of a sonata. I think those things have always stayed with me. The direct quotes from Else and Franz in my script are within double quotation marks, and everything else is either rewritten, or speculative. [At a few points in the play] I did put Franz in deep space so we’re departing a bit from historical reclamation and more of an expressionistic representation, to tell a story with a version of Franz and Else. I’m extremely dramaturgically oriented in the early process too. I believe I read a dozen or so books on them before hitting the page.

HILOBROW: The past is not entirely static; it changes with what it means to us. In this play both Franz and Else are at many times reflecting on their lives from after it’s over. There are layers of understanding added by the years Else has to reflect on him, and the historical distance at which you reflect on both of them. This stems from each one’s life being a now finished story. Franz doesn’t live long enough to have the kind of regrets he expresses here; Else survives to mourn much more than anyone deserves to. How do you think different lifespans for either might have changed the story they left behind for you to interpret?

XIA: They lived during a time when life wasn’t documented as well as now. They didn’t have texting. Or social media. Or easy access to photography. From what I’ve read I believe Franz Marc is inherently a kind person who does not have cruelty in his marrow, but he did also willingly join the army, through almost romanticism. If he had survived WWI, he might have been fundamentally changed, and abstract expressionism would’ve been quite different. There is no way for us to know. I try not to think about what could’ve been, but rather, with the knowledge of what has happened, how do we do better.

In Blue continues its world premiere at The Tank in NYC, through Dec. 15, 2019.

Images, top to bottom: photo by Asya Gorovits; The Tower of Blue Horses, 1913, Franz Marc; two more photos by Asya Gorovits; Yussuf, Prince Of Thebes, 1913, and Yussuf Models His Mother, 1920, each Else Lasker-Schüler; Deer in the Forest, 1914, Franz Marc

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE