LEAVE IT TO PSMITH (45)

By:

November 25, 2019

Leave It to Psmith (1923) is the last and most rewarding of four novels featuring the dandy, wit, and would-be adventurer Ronald Eustace Psmith, one of P.G. Wodehouse‘s most popular characters. (“One can date exactly,” Evelyn Waugh claimed, in reference to Psmith’s debut in the 1909 novel Mike, “the first moment when Wodehouse was touched by the sacred flame.”) Leave It to Psmith‘s copyright enters the public domain in 2019; HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize this terrific book here at HILOBROW. Enjoy!

The hands of the clock over the stables were pointing to half past five when Eve Halliday, tiptoeing furtively, made another descent of the stairs. Her feelings as she went were very different from those which had caused her to jump at every sound when she had started on this same journey three hours earlier.

Then, she had been a prowler in the darkness, and, as such, a fitting object of suspicion; now, if she happened to run into anybody, she was merely a girl who, unable to sleep, had risen early to take a stroll in the garden. It was a distinction that made all the difference.

Moreover, it covered the facts. She had not been able to sleep, except for an hour when she had dozed off in a chair by her window; and she certainly proposed to take a stroll in the garden. It was her intention to recover the necklace from the place where she had deposited it and bury it somewhere where no one could possibly find it.

There it could lie until she had a chance of meeting and talking to Mr. Keeble and ascertaining what was the next step he wished taken.

Two reasons had led Eve, after making her panic dash back into the house after lurking in the bushes while Baxter patrolled the terrace, to leave her precious flowerpot on the sill of the window beside the front door. She had read in stories of sensation that for purposes of concealment the most open place is the best place; and secondly, the nearer the front door she put the flowerpot the less distance would she have to carry it when the time came for its removal.

In the present excited condition of the household, with every guest an amateur detective, the spectacle of a girl tripping downstairs with a flowerpot in her arms would excite remark.

Eve felt exhilarated. She was not used to getting only one hour’s sleep in the course of a night, but excitement and the reflection that she had played a difficult game and won it against odds bore her up so strongly that she was not conscious of fatigue.

So uplifted did Eve feel that as she reached the landing above the hall she abandoned her cautious mode of progress and ran down the remaining stairs. She had the sensation of being in the last few yards of a winning race.

The hall was quite light now. Every object in it was plainly visible. There was the huge dinner gong; there was the long leather settee; there was the table which she had upset in the darkness; and there was the sill of the window by the front door. But the flowerpot which had been on it was gone.

In any community in which a sensational crime has recently been committed the feelings of the individuals who go to make up that community must of necessity vary somewhat sharply according to the degree in which the personal fortunes of each are affected by the outrage. Vivid in their own way as may be the emotions of one who sees a fellow citizen sandbagged in a quiet street, they differ in kind from those experienced by the victim himself.

And so, though the theft of Lady Constance Keeble’s diamond necklace had stirred Blandings Castle to its depths, it had not affected all those present in quite the same way. It left the house party divided into two distinct schools of thought — the one finding in the occurrence material for gloom and despondency, the other deriving from it nothing but joyful excitement.

To this latter section belonged those free young spirits who had chafed at the prospect of being herded into the drawing-room on the eventful night to listen to Psmith’s reading of Songs of Squalor. It made them tremble now to think of what they would have missed had Lady Constance’s vigilance relaxed sufficiently to enable them to execute the quiet sneak for the billiard room, of which even at the eleventh hour they had thought so wistfully. As far as the Reggies, Berties, Claudes and Archies at that moment enjoying Lord Emsworth’s hospitality were concerned, the thing was top-hole, priceless, and indisputably what the doctor ordered. They spent a great deal of their time going from one country house to another, and as a rule found the routine a little monotonous. A happening like that of the previous night gave a splendid zip to rural life. And when they reflected that, right on top of this binge, there was coming the County Ball, it seemed to them that God was in his heaven and all right with the world. They stuck cigarettes in long holders and collected in groups, chattering like starlings.

The gloomy brigade, those with hearts bowed down, listened to their effervescent babbling with wan distaste. These last were a small body numerically, but very select. Lady Constance might have been described as their head and patroness. Morning found her still in a state bordering on collapse. After breakfast, however, which she took in her room and which was sweetened by an interview with Mr. Joseph Keeble, her husband, she brightened considerably. Mr. Keeble, thought Lady Constance, behaved magnificently. She had always loved him dearly; but never so much as when, abstaining from the slightest reproach of her obstinacy in refusing to allow the jewels to be placed in the bank, he spaciously informed her that he would buy her another necklace, just as good and costing every penny as much as the old one.

It was at this point that Lady Constance almost seceded from the ranks of gloom. She kissed Mr. Keeble gratefully and attacked with something approaching animation the boiled egg at which she had been pecking when he came in.

But a few minutes later the average of despair was restored by the enrollment of Mr. Keeble in the ranks of the despondent. He had gladsomely assumed overnight that one of his agents, either Eve or Freddie, had been responsible for the disappearance of the necklace. The fact that Freddie, interviewed by stealth in his room, gapingly disclaimed any share in the matter had not damped him. He had never expected results from Freddie. But when, after leaving Lady Constance, he encountered Eve and was given a short outline of history, beginning with her acquisition of the necklace and ending — like a modern novel — on the somber note of her finding the flowerpot gone, he, too, sat him down and mourned as deeply as anyone.

Passing with a brief mention over Freddie, whose morose bearing was the subject of considerable comment among the younger set; over Lord Emsworth, who woke at twelve o’clock disgusted to find that he had missed several hours among his beloved flower beds; and over the Efficient Baxter, who was roused from sleep at 12:15 by Thomas the footman knocking on his door in order to hand him a note from his employer inclosing a check and dispensing with his services; we come to Miss Peavey.

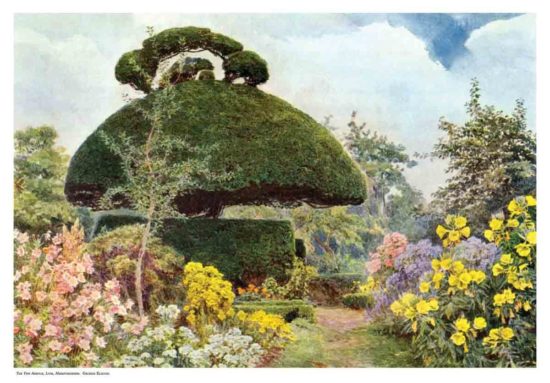

At twenty minutes past eleven on this morning when so much was happening to so many people, Miss Peavey stood in the Yew Alley gazing belligerently at the stemless mushroom finial of a tree about halfway between the entrance and the point where the alley merged into the west wood. She appeared to be soliloquizing. For, though words were proceeding from her with considerable rapidity, there seemed to be no one in sight to whom they were being addressed. Only an exceptionally keen observer would have noted a slight significant quivering among the tree’s tightly woven branches.

“You poor bone-headed fish,” the poetess was saying with that strained tenseness which results from the churning up of a generous and emotional nature, “isn’t there anything in this world you can do without tumbling over your feet and making a mess of it? All I ask of you is to stroll round under a window and pick up a few jewels, and now you come and tell me ——”

“But, Liz!” said the tree plaintively.

“I do all the difficult part of the job. All that there was left for you to handle was something a child of three could have done on its ear. And now ——”

“But, Liz! I’m telling you I couldn’t find the stuff! I was down there all right, but I couldn’t find it!”

“You couldn’t find it!” Miss Peavey pawed restlessly at the soft turf with a shapely shoe. “You’re the sort of dumb Isaac that couldn’t find a bass drum in a telephone booth. You didn’t look!”

“I did look! Honest, I did!”

“Well, the stuff was there. I threw it down the moment the lights went out.”

“Somebody must have got there first and swiped it.”

“Who could have got there first? Everybody was up in the room where I was…. Am I sure? Am I ——” The poetess’ voice trailed off. She was staring down the Yew Alley at a couple who had just entered. She hissed a warning in a sharp undertone. “H-s-st! Cheese it, Ed! There’s someone coming.”

The two intruders who had caused Miss Peavey to suspend her remarks to her erring lieutenant were of opposite sexes — a tall girl with fair hair and a taller young man irreproachably clad in white flannels who beamed down at his companion through a single eyeglass. Miss Peavey gazed at them searchingly as they approached. A sudden thought had come to her at the sight of them. Mistrusting Psmith as she had done ever since Mr. Cootes had unmasked him for the impostor that he was, the fact that they were so often together had led her to extend her suspicion to Eve. It might, of course, be nothing but a casual friendship, begun here at the castle; but Miss Peavey had always felt that Eve would bear watching. And now, seeing them together again this morning, it had suddenly come to her that she did not recall having observed Eve among the gathering in the drawing-room last night. True, there had been many people present; but Eve’s appearance was striking, and she was sure that she would have noticed her if she had been there. And if she had not been there, why should she not have been on the terrace? Somebody had been on the terrace last night, that was certain. For all her censorious attitude in their recent conversation, Miss Peavey had not really in her heart believed that even a dumb-bell like Eddie Cootes would not have found the necklace if it had been lying under the window on his arrival.

“Oh, good morning,” she cooed. “I’m feeling so upset about this terrible affair. Aren’t you, Miss Halliday?”

“Yes,” said Eve, and she had never said a more truthful word.

Psmith, for his part, was in more debonair and cheerful mood even than was his wont. He had examined the position of affairs and found life good. He was particularly pleased with the fact that he had persuaded Eve to stroll with him this morning and inspect his cottage in the woods. Buoyant as was his temperament, he had been half afraid that last night’s interview on the terrace might have had disastrous effects on their intimacy. He was now feeling full of kindliness and good will towards all mankind — even Miss Peavey — and he bestowed on the poetess a dazzling smile.

“We must always,” he said, “endeavor to look on the bright side. It was a pity, no doubt, that my reading last night had to be stopped at a cost of about twenty thousand pounds to the Keeble coffers; but let us not forget that but for that timely interruption I should have gone on for about another hour. I am like that. My friends have frequently told me that when once I start talking it requires something in the nature of a cataclysm to stop me. But, of course, there are drawbacks to everything, and last night’s rannygazoo perhaps shook your nervous system to an extent greater than we at first realized.”

“I was dreadfully frightened,” said Miss Peavey. She turned to Eve with a delicate shiver. “Weren’t you, Miss Halliday?”

“I wasn’t there,” said Eve absently.

“Miss Halliday,” explained Psmith, “has had, the last few days, some little experience of myself as orator, and with her usual good sense decided not to go out of her way to get more of me than was absolutely necessary. I was perhaps a trifle wounded at the moment, but on thinking it over came to the conclusion that she was perfectly justified in her attitude. I endeavor always in my conversation to instruct, elevate and entertain, but there is no gainsaying the fact that a purist might consider enough of my chit-chat to be sufficient. Such, at any rate, was Miss Halliday’s view, and I honor her for it. But here I am rambling on again just when I can see that you wish to be alone. We will leave you, therefore, to muse. No doubt we have been interrupting a train of thought which would have resulted but for my arrival in a rondel or a ballade or some other poetic morceau. Come, Miss Halliday. A weird and repellent female,” he said to Eve as they drew out of hearing, “created for some purpose which I cannot fathom. Everything in this world, I like to think, is placed there for some useful end; but why the authorities unleashed Miss Peavey on us is beyond me. It is not too much to say that she gives me a pain in the gizzard.”

Miss Peavey, unaware of these harsh views, had watched them out of sight; and now she turned excitedly to the tree which sheltered her ally.

“Ed!”

“Hello!” replied the muffled voice of Mr. Cootes.

“Did you hear?”

“No.”

“Oh, my heavens!” cried his overwrought partner. “He’s gone deaf now! That girl — you didn’t hear what she was saying? She said that she wasn’t in the drawing-room when those lights went out. Ed, she was down below on the terrace; that’s where she was, picking up the stuff. And if it isn’t hidden somewheres in that McTodd guy’s shack down there in the woods I’ll eat my Sunday rubbers.”

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.