OFF-TOPIC (11)

By:

November 16, 2019

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This month, two recurring dreams of the industrial heartland converge, in remembrances of lives lived and left by native sons of the iron wilds, just towns and worlds apart…

How do we do the things we do? We could have been anything…and when anything doesn’t happen, how do we go on, and how could we have done, said, acted the way we did? How could anything have been different?

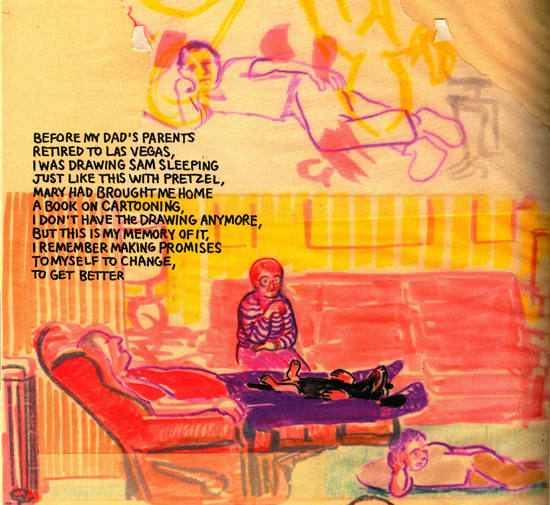

The Temptations’ refrain runs through much of Frank Santoro’s masterful graphic memoir Pittsburgh, sometimes with accompanying cartoon musical-note symbols, sometimes just as a stage-direction for what’s happening in the background — a chorus come loose from the drama it’s witnessing, seeping away into the horizon, in quiet contrast to those licensed standards that blare over period-piece movies to let you know you’re in the past.

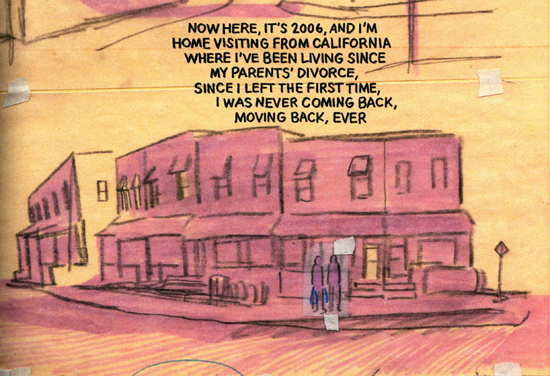

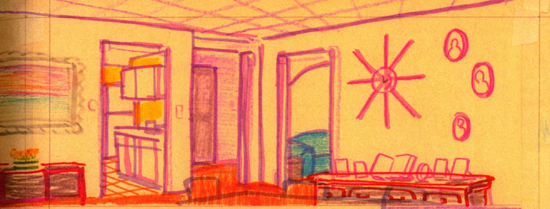

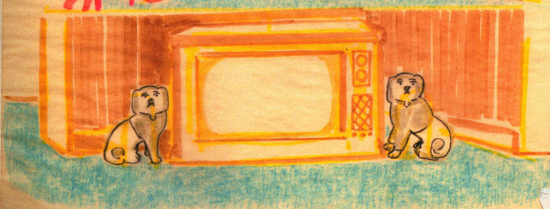

Santoro titles his reminiscence after his home town perhaps because he knows he will fade from the scene one day as well. Schooled in temporariness by divorced parents and a long family history of comings and goings (either off to war or not very far, between battling relatives’ different houses), Santoro’s stupendously assured style is made to seem sketchy, preliminary, transient. Often characters are taped into the scene, like paper dolls, rearrangement of possible realities, rough drafts of our own life stories; the figures themselves are just as often modeled with full flesh, but it’s the backdrops that will endure.

This itself invokes a kind of movement; the positive propulsion of existing, whether or not you get out of your declining town (as many people in this book do, and even more dream). The streets and alleyways and factories and stores of Pittsburgh, and the wilderness still left beyond and around them, are what stay still, and Santoro’s pans around the industrial vistas and timeless rivers are majestic as well as melancholy. Yet in their stillness, filled with life, even when empty of people and neighborhood dogs — this is not the modern cliché of “setting as character,” but more like the Native American idea of the land being a kind of outer skin for those who exist on it; no matter how ephemeral Santoro’s marks are, the mark of his life and his community’s will remain upon this silent scene.

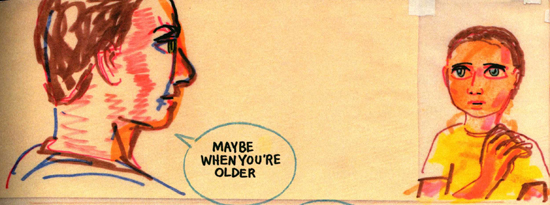

The landscape is pictured at a distance that Santoro seems no longer to desire, and which in any case he can no longer count on; Pittsburgh is like a message-in-a-bottle rolled out on dry land, a time-capsule left aboveground for everyone to see while its sender and main recipients are all still in this world. At one point 6-year-old Frank comes upon his 28-year-old dad journaling in a yellow pad, and begs to read it. His dad has been writing down a nightmare from his time in Vietnam, and misgivings about his homelife that, to his son, might be even more disturbing. “Junior,” as he’s known by everyone, assents to his dad’s plea not to read it; forbidden knowledge in the eden of his youth.

We can assume that the grown-up Santoro was shown every word, though there are some things in this book it’s surprising that he’d leave out in the open for himself to read — at one point he tells us, “Even my closest friends know that I’m just a tourist passing through the little town that is our acquaintance” — though he may also be showing us (and himself) that there’s only one way to break the locks on the truth, even if getting ourselves set free is still a work in progress.

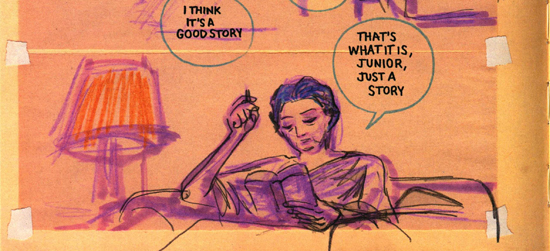

Admissions like that perhaps redeem the unfilled space of what his dad would not show him. Still, collecting the facts is different than solving the mysteries; as he reads back through his life to make sense of the story, we see some of the unbreakable circles it moves in: Toward the front of the book, Frank’s voiceover remarks that his mom and dad only even speak to each other anymore at funerals, or, “maybe at my wedding, if that ever happens”; more than a hundred pages later, on a drive with his mom when he asks about her and dad speaking again “more than just to say hello at a funeral,” she answers, “Maybe at your wedding, if that ever happens” — and we see how much of our story is pre-written for us; the unknowing echoes of what our elders put in our mouths, and heads.

In one remarkable scene, Frank is trying to process revelations from his dad (which cover much of the ground in that long-ago unshared diary entry about his domestic unhappiness); in Frank’s mind’s-eye we’re seeing a row of houses on fire (itself a reference to some disaster his mom mentions briefly but which, in this narrative, remains repressed). As he steadies himself with an internal monologue, we see the houses whole again, as flames rise from Frank’s figure; the fire contained, breathed back into himself, but neither extinguished nor warming.

It gives nothing away to note the surrounding, unpopulated portraits of Pittsburgh that end the book; panoramas in a petroleum rainbow, a reverse arcadia to the Hudson River School’s ideals, but home. There are stories yet to end, and futures of uncertainty ahead. But art like Pittsburgh makes the world worth staying in, and the life it records is a book its author is doing his best to keep open.

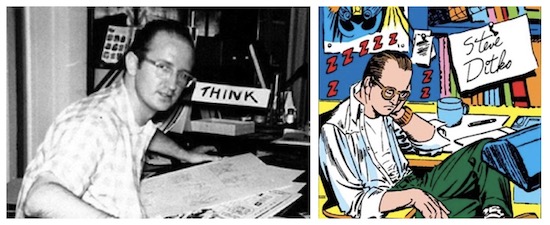

One artist whose journey into himself remained a solitary one was Steve Ditko, admired and enigmatic creator or co-creator of Spider-Man, Doctor Strange, Shade the Changing Man, Hawk & Dove and Squirrel Girl among many more. He closed the book behind him when he died at age 90 last year, but the quest to paint his portrait from memory has begun, with Lenny Schwartz’s play titled simply Ditko, which had a brief showcase a few days before the start of New York Comic Con 2019.

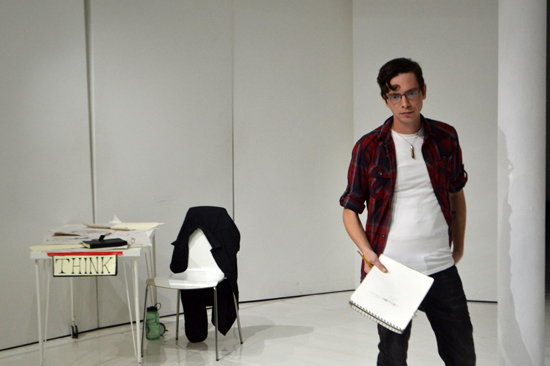

The artist was famous for being elusive, a face not seen in photographs since the early 1960s and seen by most in-person through the sliver of his studio door in an office building near Times Square, where fans and younger fellow professionals would make pilgrimages to discuss the past and typically be turned away while Ditko got back to work. In the play, which is set in his mind but after his death, we enter at the point where the last page will be left blank; the stark white box in which his life replays, sometimes fully within the frame, so to speak, with straight reenactments of events, and sometimes with Ditko commenting from the borders, assessing the moments of his life.

Those flash before us — there is a lot to cover in this brisk play — but Ditko himself is an island of calm, dedicated to his craft and stoic in his principles. A native of Johnstown, PA, the genesis of his ceaseless work ethic is clear and well-summarized in the play’s scenes of his modest upbringing (and it is one that viewers will recognize from his fellow rust-belt changeling, Andy Warhol). Disputes with perceived overseers like Stan Lee and dialogues with imagined idols like Ayn Rand define the course of his life as we see it here, and in the end the real Ditko, whoever he may be, disappears back to his drawing board.

Derek Laurendeau is deeply moving in the title role, though like the disputed portrayal of Bela Lugosi by Martin Landau in Ed Wood, the feelings may be closer to the truth than to the facts. Those few people I know who knew Ditko paint quite a different picture than the masses had to fill in for themselves, but Laurendeau’s characterization, solitary while not superior, sad yet serene, is a study in decent individuality, whatever the limitations and loneliness, which seems to do an honest honor to the subject.

Many think of Ditko as hard to get close to, but the playwright relied on surviving relatives of the artist, none more than his nephew Mark, who is said to have called the role as Schwartz has written it “close enough.” What most of us have to go on from Ditko’s own words are his intricate screeds on creative credit and social ethics. The play often has him embody and orate the positions he took, though Ditko’s colleague and former Marvel Editor in Chief Tom DeFalco, who was in the audience the same night as I, reported that Ditko did not talk the way he wrote: “I always found him very friendly, very open… Steve was a regular guy. I had a coffeepot in my office, and he’d come in, pour himself a cup of coffee, and we would talk about… anything. An article in the newspaper, that sort of thing. Nothing ever personal. I thought back on it, and the strange thing is, he’d come in and we’d talk for an hour or two and then he’d go back to work, and we never once discussed comics!”

Though DeFalco’s not depicted in the play, he was the one who brought about the least disputed incident in it, when Ditko and Stan Lee reunited at the Marvel offices to discuss the project which became Lee’s Ravage 2099. Ditko passed, but DeFalco confirms that the spirited idea-session and affectionate reunion we see here was real. As Lee, Geoff White largely leans (quite amusingly) on the public, circus-barker Stan, but at moments like this last meeting (and earlier disputes, even though those may be happening just in Ditko’s head), White also nails the wistful, sentimental Stan behind the curtain, the man who could never understand the ill-will some of his most legendary partnerships ended in.

The play doesn’t follow Ditko through much of the long years after, when he was a kind of Salinger-in-plain-sight, profusely turning out his strange, hieroglyphic-like philosophical indie comics; rumored to be living in his studio; reportedly getting generous royalty checks from the Spider-Man movies (which he deserved but denied); and being visited by a steady procession of (often rebuffed) acolytes, well-wishers and gawkers. Part of that story was picked up by another theatregoer the night I was there, comics writer-artist (and my eternal friend and occasional collaborator) Dean Haspiel. “I think…it was four or five times? I went [to see Ditko] not only as a fan, but also to show my work, to just get a review or a thought or something. And I had been working on Cuba: My Revolution at the time for Vertigo. I don’t remember what he said, but he was really intrigued with Castro, and Cuba. And I told him how it was my mom’s friend who had written this story, and he was really interested in that. So I was able to get to talk with him — in the front of his door. He had it cracked open, and he always looked a little disheveled, like he had just buttoned up his shirt, and maybe had one shoe on. The sense you would get was that he was always working, ’cuz that’s what he did. The last time I was near his studio, I elected to not go, because I felt like I would have bothered him at that point. I was just trying to say thank-you. Thank you for all the great work, and for influencing me in some way. And then just trying to talk to a person; get to know this person that famously no one really knows about. … And that’s his right. In a world where everyone is just exposing themselves, 24/7 — he didn’t need to do that.”

Now that Ditko is himself a story, those who need to know him will travel back often, and without any more fear of him or his legacy being disturbed. Ditko is a welcome first trip.

Images: Uncredited photo of the artist, circa 1959; self-portrait (detail) from Amazing Spider-Man Annual #1 (1964); Ditko production photos by Duncan Pflaster

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE