LEAVE IT TO PSMITH (43)

By:

November 12, 2019

Leave It to Psmith (1923) is the last and most rewarding of four novels featuring the dandy, wit, and would-be adventurer Ronald Eustace Psmith, one of P.G. Wodehouse‘s most popular characters. (“One can date exactly,” Evelyn Waugh claimed, in reference to Psmith’s debut in the 1909 novel Mike, “the first moment when Wodehouse was touched by the sacred flame.”) Leave It to Psmith‘s copyright enters the public domain in 2019; HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize this terrific book here at HILOBROW. Enjoy!

The ability to sleep soundly and deeply is the prerogative, as has been pointed out earlier in this straightforward narrative of the simple home life of the English upper classes, of those who do not think quickly. The Earl of Emsworth, who had not thought quickly since the occasion in the summer of 1874 when he had heard his father’s footsteps approaching the stable loft in which he, a lad of fifteen, sat smoking his first cigar, was an excellent sleeper. He started early and finished late. It was his gentle boast that for more than twenty years he had never missed his full eight hours. Generally he managed to get something nearer ten.

But then, as a rule, people did not fling flowerpots through his window at four in the morning.

Even under this unusual handicap, however, he struggled bravely to preserve his record. The first of Baxter’s missiles, falling on a settee, produced no change in his regular breathing. The second, which struck the carpet, caused him to stir. It was the third, colliding sharply with his humped back, that definitely woke him. He sat up in bed and stared at the thing.

In the first moment of his waking relief was, oddly enough, his chief emotion. The blow had roused him from a disquieting dream in which he had been arguing with Angus McAllister about early spring bulbs, and McAllister, worsted verbally, had hit him in the ribs with a spud. Even in his dream Lord Emsworth had been perplexed as to what his next move ought to be, and when he found himself awake and in his bedroom he was at first merely thankful that the necessity for making a decision had been postponed. Angus McAllister might on some future occasion smite him with a spud, but he had not done it yet.

There followed a period of vague bewilderment. He looked at the flowerpot. It held no message for him. He had not put it there. He never took flowerpots to bed. Once, as a child, he had taken a dead pet rabbit, but never a flowerpot. The whole affair was completely inscrutable; and his lordship, unable to solve the mystery, was on the point of taking the statesmanlike course of going to sleep again, when something large and solid whizzed through the open window and crashed against the wall, where it broke, but not into such small fragments that he could not perceive that in its prime it, too, had been a flowerpot. And at this moment his eyes fell on the carpet and then on the settee, and the affair passed still further into the realm of the inexplicable. The Hon. Freddie Threepwood, who had a poor singing voice but was a game trier, had been annoying his father of late by crooning a ballad ending in the words:

It is not raining rain at all;

It’s raining vi-o-lets.

It seemed to Lord Emsworth now that matters had gone a step farther. It was raining flowerpots.

The customary attitude of the Earl of Emsworth towards all mundane affairs was one of vague detachment; but this phenomenon was so remarkable that he found himself stirred to quite a little flutter of excitement and interest. His brain still refused to cope with the problem of why anybody should be throwing flowerpots into his room at this hour — or, indeed, at any hour; but it seemed a good idea to go and ascertain who this peculiar person was.

He put on his glasses and hopped out of bed and trotted to the window. And it was while he was on his way there that memory stirred in him, as some minutes ago it had stirred in the Efficient Baxter. He recalled that odd episode of a few days back, when that delightful girl, Miss What’s-Her-Name, had informed him that his secretary had been throwing flowerpots at that poet fellow, McTodd. He had been annoyed, he remembered, that Baxter should so far have forgotten himself. Now, he found himself more frightened than annoyed. Just as every dog is permitted one bite without having its sanity questioned, so, if you consider it in a broadminded way, may every man be allowed to throw one flowerpot. But let the thing become a habit and we look askance. This strange hobby of his appeared to be growing on Baxter like a drug, and Lord Emsworth did not like it at all. He had never before suspected his secretary of an unbalanced mind; but now he mused, as he tiptoed cautiously to the window, that the Baxter sort of man, the energetic, restless type, was just the kind that does go off his head. Just some such calamity as this, his lordship felt, he might have foreseen. Day in, day out Rupert Baxter had been exercising his brain ever since he had come to the castle, and now he had gone and sprained it. Lord Emsworth peeped timidly out from behind a curtain.

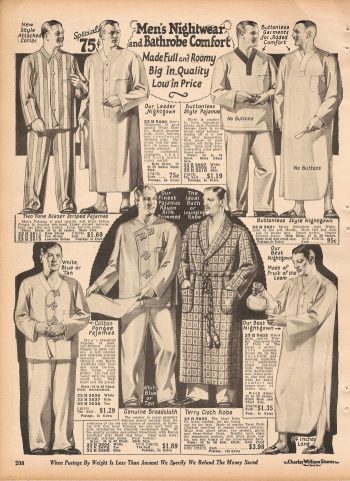

His worst fears were realized. It was Baxter, sure enough; and a tousled, wild-eyed Baxter, incredibly clad in lemon-colored pajamas.

Lord Emsworth stepped back from the window. He had seen sufficient. The pajamas had in some curious way set the coping stone on his dismay, and he was now in a condition approximating to panic. That Baxter should be so irresistibly impelled by his strange mania as actually to omit to attire himself decently before going out on one of these flowerpot-hurling expeditions of his seemed to make it all so sad and hopeless.

The dreamy peer was no poltroon, but he was past his first youth, and it came to him very forcibly that the interviewing and pacifying of secretaries who ran amuck was young man’s work. He stole across the room and opened the door. It was his purpose to put this matter into the hands of an agent.

Keeping to the corridor in which his bedroom was situated, his lordship had the choice of about a dozen rooms to which to apply for assistance. He stood there hesitating for a moment, wondering on which door to knock; and his selection was finally determined by a brain wave which, as being the only one he had ever had in his life, should be noted and spread upon the records. It was probably due entirely to fear; but there it is; he had it, and should be given the credit.

The corridor in which he stood was dotted at intervals along its length with pairs of boots, placed there by the occupants of the various rooms to be ready for early morning collection by the official cleaner. With superb common sense Lord Emsworth simply made a bee line for the door before which reposed the largest pair. And so it came about that Psmith, who was two inches over six feet in height and wore footgear in proportion, was aroused from slumber by a touch on the arm and sat up to find his host’s pale face peering at him in the weird light of early morning.

“My dear fellow,” quavered Lord Emsworth.

Psmith, like Baxter, was a light sleeper; and it was only a moment before he was wide awake and exerting himself to do the courtesies.

“Good morning,” he said pleasantly. “Will you take a seat?”

“I am extremely sorry to be obliged to wake you, my dear fellow,” said his lordship; “but the fact of the matter is, my secretary, Baxter, has gone off his head.”

“Much?” inquired Psmith, interested.

“He is out in the garden in his pajamas, throwing flowerpots through my window.”

“Flowerpots?”

“Flowerpots!”

“Oh, flowerpots!” said Psmith, frowning thoughtfully, as if he had expected it would be something else. “And what steps are you proposing to take? That is to say,” he went on, “unless you wish him to continue throwing flowerpots.”

“My dear fellow ——”

“Some people like it,” explained Psmith. “But you do not? Quite so, quite so. I understand perfectly. We all have our likes and dislikes. Well, what would you suggest?”

“I was hoping that you might consent to go down — er — having possibly armed yourself with a good stout stick — and induce him to desist and return to bed.”

“A sound suggestion in which I can see no flaw,” said Psmith approvingly. “If you will make yourself at home in here — pardon me for issuing invitations to you in your own house — I will see what can be done. I have always found Comrade Baxter a reasonable man, ready to welcome suggestions from outside sources, and I have no doubt that we shall easily be able to reach some arrangement.”

He got out of bed, and having put on his slippers and his monocle, paused before the mirror to brush his hair with extreme care.

“For,” he explained, “one must be natty when entering the presence of a Baxter.”

He went to the closet and took from among a number of hats a neat Homburg. Then, having selected from a bowl of flowers on the mantelpiece a simple white rose, he pinned it in the coat of his pajama suit and announced himself ready.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.