Best YA & YYA Lit 1970

By:

November 1, 2019

The following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Sixties (1964–1973) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite YA and YYA adventures published in 1970. Enjoy!

- Peter Dickinson’s YA fantasy adventure The Devil’s Children. When a mysterious enchantment settles over England, many of its white, working-class inhabitants revert to an ignorant, xenophobic way of looking at the world. They become technophobes, persecute anyone who isn’t perturbed by machinery as witches, and return to farming and an old-fashioned life. Nicky, a 12-year-old girl living in London, loses her parents when they — and nearly every other adult in the city — smash their TVs and refrigerators, cars and buses, and every other sort of machine. Nicky, too, is affected by the Changes, to some extent — machinery makes her uneasy, though not violent. When a group of Sikhs — who, in post-Changes England, are considered “devil’s children” — travels through the city en route to finding a safe, permanent home in the countryside, Nicky joins their caravan. (Note that Dickinson’s use of Sikhs as central characters is, one assumes a commentary on the cultural moment: In 1967, a Sikh bus driver, Tarsem Singh Sandhu from Wolverhampton, was sacked from his job after he refused to remove his turban and shave his beard. Six thousand Sikhs marched in protest. Wolverhampton MP Enoch Powell made a now infamous 1968 speech defending discrimination on the grounds of race in certain areas of British life.) Nicky learns to love and respect her adopted family, who prove to be courageous, smart, and adaptable. After some adventures, the group establishes themselves in a new home near a farming community — the leader of which is a fat, hate-mongering populist reminiscent of Donald Trump. When a group of raiders attacks the community, Nicky and her brave friends rush to their rescue. There’s a climactic neo-medieval battle scene…. Fun facts: Although it was published third in the Changes series, The Devil’s Children is chronologically the earliest. I have suggested elsewhere that this book and the others in the series — really should be adapted as a movie or TV show.

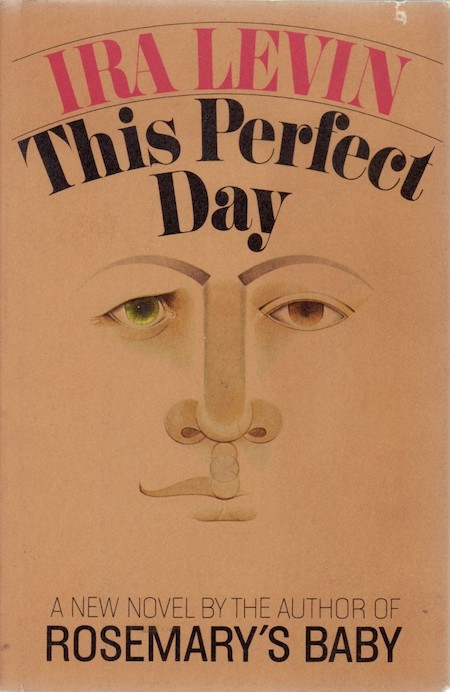

- John Christopher’s sci-fi adventure The Guardians. A century in the future, England is divided into the modern, overpopulated, high-tech Conurbs and the leisurely, aristocratic County. Thirteen-year-old Rob grew up in the Conurbs, but his mother was from the County; so when his father dies suspiciously, he flees the state boarding school and sneaks under the barrier separating the two areas. There, he’s befriended by Mike Gifford, a boy his own age, and eventually taken in by the Gifford family. They’re kind to him, though Mr. Gifford is strangely obsessed with bonsai — and little else. Chastened by what he learns about the outside world from Rob, Mike falls under the influence of seditious types — who question England’s authoritarian regime and social injustice. Rob, meanwhile, doesn’t want to rock the boat. When Oxford and Bristol are taken by armed rebels, Mike and Rob find themselves on opposing sides of the conflict. Now it’s Mike’s turn to flee across the border — into the Conurbs, as a refugee from justice. Rob, meanwhile, is recruited by the Guardians — a secret group of overseers (a sinister version of H.G. Wells’s “Samurai”) who will do whatever is necessary to maintain the status quo. If Mike is caught, Rob learns, he’ll be subjected to a surgical procedure to render him docile… like Mr. Gifford. Where do his true loyalties lie? PS: Interesting to note the parallels between this story and Ira Levin’s This Perfect Day, published the same year. Fun facts: Written at the height of the author’s powers, between the Tripods trilogy (1967–1968) and the the Sword of the Spirits trilogy (1979–1972), The Guardians won the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize.

- Glendon Swarthout’s YA adventure Bless the Beasts and Children. At a boys’ camp in Prescott, Arizona, six emotionally troubled adolescents find themselves bunking together… because the well-adjusted assholes have rejected them. Their ragtag group — John Cotton, Sammy Shecker, Lawrence Teft III, Gerald Goodenow, and quarrelsome brothers Lally 1 and Lally 2 — is dubbed the Bedwetters. They’re treated cruelly not only by their peers, but by the camp’s counselors; via flashbacks, we discover how lazy and inattentive their wealthy parents are. Having discovered their cabin counselor’s stash of pornography and booze, they blackmail him into taking them for a jaunt offsite, to a nearby ranch… where, alas, things get even darker. There, they witness a grim scene of surplus bison being “hunted” for sport; it’s a slaughter. Determined to rescue the remaining animals, Cotton and his crew of empathetic misfits steal horses, then a pickup truck, and make their way back to the ranch that night. It’s a harrowing journey, and at its end they discover that the nearly tame bison can’t be moved — even when the exit gate is opened. The ending is truly tragic; children should not watch this movie. Fun facts: Several of Swarthout’s novels were adapted as movies, including Where the Boys Are (1960) and The Shootist. The tragic 1971 adaptation of Bless the Beasts and Children, the authors bestselling book, was directed by Stanley Kramer and starred Billy Mumy (Will Robinson from Lost in Space). In response to the book’s popularity, the Arizona legislature mandated changing the regulation of their annual buffalo hunt to more humane practices.

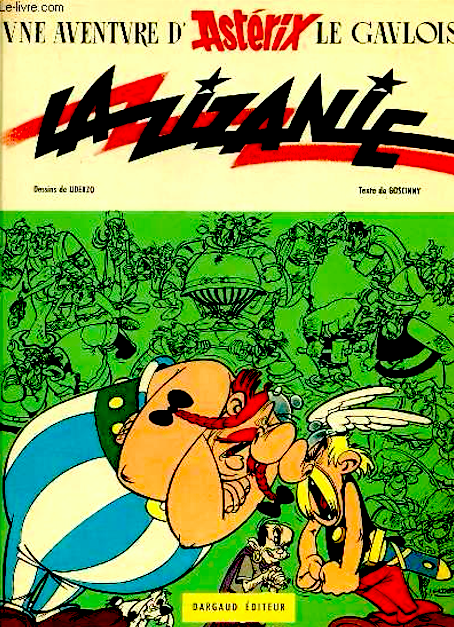

- René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s La Zizanie (English title: Asterix and the Roman Agent). As the 15th Asterix adventure begins, Julius Caesar releases Tortuous Convolvulus, a seditious troublemaker, from prison — and sends him to Gaul. Wherever this fellow goes, it seems, jealousy and discord (the book’s original title was Strife) follow. (Earlier, he’d been sentenced to the lions in the circus, but somehow he persuaded the lions to eat one another instead.) En route to Gaul, Convolvulus causes dissension among Romans, galley slaves, and the pirates. Once he arrives at Asterix’s village, Convolvulus gives a valuable vase to Asterix, whom he describes as the “most important man in the village,” which naturally causes dissension. He also starts a rumor that Asterix has been feted by the Romans because he’s given them the secret of Getafix’s magic potion. Meanwhile, the soldiers in the nearby Roman camp of Aquarium begin to turn on one another. When Asterix and Obelix declare their intention of leaving forever, the Romans prepare to wipe out the village once and for all. Fun facts: The story was serialized in Pilote magazine in 1970; it was translated into English in 1972.

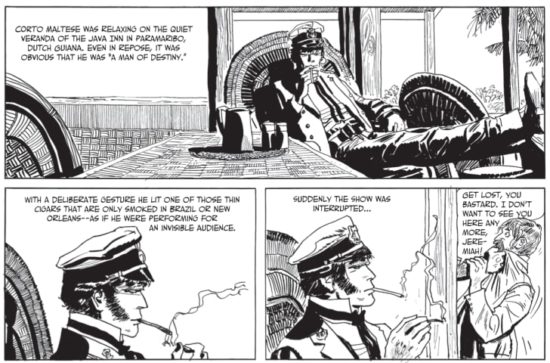

- Hugo Pratt‘s Corto Maltese stories (serialized 1970–on). Pratt’s now-iconic adventurer character debuted in the graphic novel “Una ballata del mare salato” (serialized 1967). In 1970, Pratt began publishing 20-pp. Corto Maltese stories in the French magazine Pif Gadget; set on the eve of World War I, they are cinematic, allusive, hallucinogenic, elegant, thrilling. In “Tristan Bantam” (“The Secret of Tristan Bantam”), Corto first meets the scholar Steiner, in Paramaribo; Steiner diagnoses our hero as a “frustrated Boy Scout,” before joining him and the titular English orphan, Tristan, on a treasure hunt — which involves a cryptic map and the myth of Mu, a lost continent. In “Rendez–vous à Bahia” (“Rendez-Vous in Bahia”), the trio encounter Tristan’s half-sister, the voodoo practitioner Morgana. They confront the villanous Milner, who plots to steal the orphans’ inheritance; and Tristan retrieves Tezcatlipoca’s skull from another dimension. In “Samba avec Tir Fixe” (“Sureshot Samba”), we arrive in Brazil, where Gold Mouth, an apparently ancient voodoo practitioner, sends Corto upriver to deliver guns and money to anti-colonialist rebels; they fall in with Sure Shot, teenage leader of a group of cangaceiros — peasant bandits — whom Corto inspires to bring down an exploitative colonial administrator. In “L’aigle du Brésil” (“The Brazilian Eagle”), Corto and crew stumble upon a German gunboat disguised as a banana cargo boat — and learn that Gold Mouth and Morgana are not what they seem. In “…et nous reparlerons des gentilshommes de fortune…” (“So Much for Gentlemen of Fortune”), “A cause d’une mouette” (“The Seagull’s Fault”), and “Têtes et champignons” (“Mushroom Heads”), the hunt for long-lost treasure continues — and Corto’s nemesis, Rasputin, returns! Fun facts: “When I want to relax, I read an essay by Engels,” Umberto Eco once wrote. “When I want something more serious to read, I read Corto Maltese.” The publisher NBM collected the 1970 Pif Gadget stories in two albums: The Brazilian Eagle (1979) and Banana Conga (1979; the title story is from 1971.) In 2015, the publisher IDW began reissuing all the Corto Maltese stories.

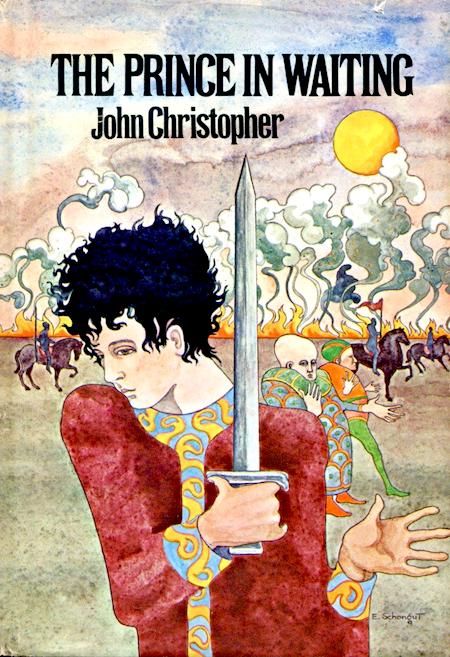

- John Christopher’s Sword of the Spirits sci-fi adventure The Prince in Waiting. The first installment in one of my favorite YA sci-fi trilogies. Thirteen-year-old Luke is the son of an army captain in Winchester, a walled and fortified city-state whose prince regularly leads an attack on neighboring city-states for honor and glory. Although at first we may think the story is set in medieval England, we soon figure out that this is a post-apocalyptic future. There has been some sort of autochthonic catastrophe, which decimated the 20th-century population and released radiation — which has created “polymufs” (mutants), and even a monster or two. Dwarfs are second-class citizens, in the neo-medieval world of Winchester and its neighboring cities; so are Christians, for that matter, who are widely regarded as weak and worthless. (As in Cicely Hamilton’s 1922 sci-fi novel Theodore Savage, science and technology is regarded with superstitious horror, the cause of humankind’s downfall.) Machinations by the prince’s captains, as well as by the Seers — the dominant religious order, who condemn science and technology while communing with spirits — results in Luke’s father becoming Winchester’s new prince. The adolescent Luke — not his illegitimate older brother, Peter — becomes the titular prince in waiting. The King Arthur mythos is somewhere in the background, here: Will Luke’s father, or Luke himself, unite England’s fractious city-states into one kingdom? Like all of Christopher’s protagonists, Luke is a complex character — not entirely sympathetic. We root for him to succeed, and also to overcome his own demons. Fun facts: A sequel, Beyond the Burning Lands, was published in 1971. The trilogy’s third installment, The Sword of the Spirits, was published in 1972.

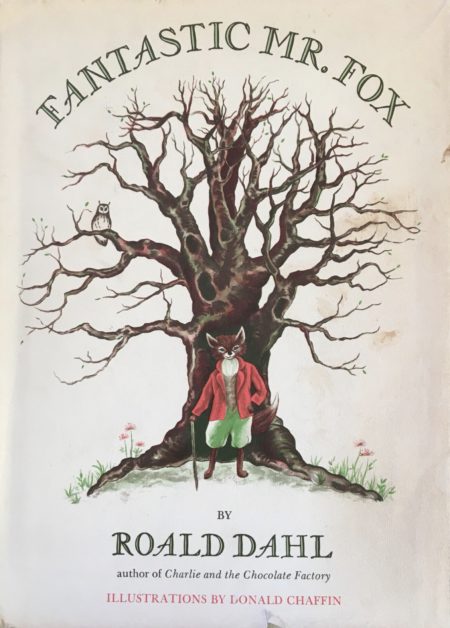

- Roald Dahl‘s children’s adventure Fantastic Mr Fox. The wily Mr. Fox, who lives in a hillside den, supports his wife and children by making nocturnal raids on the farms and storehouses of Boggis, Bunce and Bean — wicked, cruel, stupid farmers. When the farmers unite to kill our hero, they manage to shoot off his tail — then dig up his burrow, with spades and eventually heavy excavation machinery. Mr. Fox and his family retreat further underground, where they’re trapped; as long as the siege lasts, not only they but their neighbors will slowly starve to death. Finally, Mr. Fox and his children tunnel underground to Boggis’s, Bunce’s and Bean’s farms — and they invite their fellow animals along for the fun. They steal ducks, geese, hams, bacon, carrots (for their rabbit neighbors), even hard cider. Mr. Fox and his neighbors establish an idyllic underground commune, where no one will ever go hungry. Dahl strongly suggests that the animals have a right to prey on the humans because whereas the animals create delicious meals, the farmers are disgusting: one eats endless chickens, another drinks only alcoholic cider, and a third subsists on doughnuts stuffed with goose liver paste. Wit triumphs over shit; Zivilisation over Kultur. Fun facts: Wes Anderson’s 2009 film adaptation takes liberties with the original story, but it’s an excellent evocation of Dahl’s sensibility: Beastly people must be punished.

- Ira Levin’s YA sci-fi adventure This Perfect Day. In the far future, the things that divide humankind — race, class, nationality — no longer do. Thanks to the visionary leadership of Wei Li Chun and Bob Wood, all nations have unified into one world state; all races and ethnicities have merged into one “family”; and everyone has a job, a place to live, and enough to eat. Although there are downsides to this utopian state of affairs — there is very little freedom to choose what you’ll do, where you’ll live, or who you’ll marry; instead of surnames, everyone is issued a “namenumber”; people eat “totalcakes” and drink “cokes” for each meal; and so forth — nobody complains, thanks to mandatory monthly administrations of mood-altering drugs. We’ve seen this sort of dystopia before, and for a while Levin’s book follows a familiar plot. Chip, a youthful rebel, stops taking his meds, and discovers that “UniComp,” the computer that regulates the activities of everyone on the planet, is administered by a caste of Programmers who live in a luxurious underground kingdom. (Even more shocking is the revelation that Wei Li Chun is still alive, thanks to his practice of having his head transplanted every so often onto a young body!) Our hero escapes to a commune-like settlement, only to discover that it, too, is under the control of the world-state. When he joins with other rebels in an effort to overthrow the Programmers, he learns the most shocking secret of all. A decent potboiler, though seriously marred by sexism and homophobia. Fun facts: Ira Levin is best known as author of the novels A Kiss Before Dying (1953), Rosemary’s Baby (1967), The Stepford Wives (1972), and The Boys from Brazil (1976), all of which were adapted into successful movies. This underappreciated novel hasn’t been adapted.

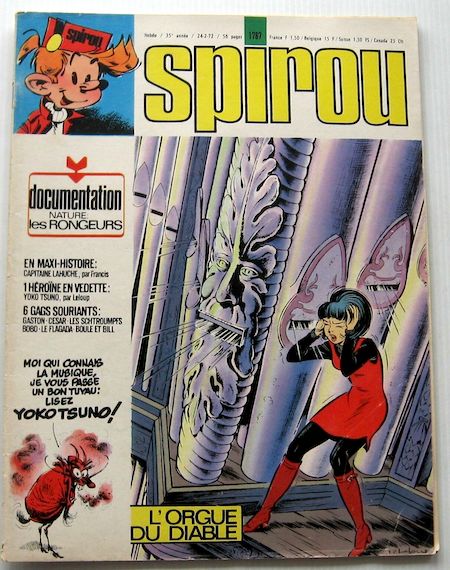

- Roger Leloup’s sci-fi comic strip Yoko Tsuno (serialized 1970–2012). The protagonist of this long-running Franco-Belgian strip Yoko Tsuno is a brilliant young Japanese engineer who can do everything from programming a computer to flying a plane; she also speaks several languages, and is proficient in several martial arts. Along with her Belgian friends Vic Video and Pol Pitron, Yoko travels around Europe and Asia solving mysteries and getting into and out of futuristic scrapes. Some of the adventures of the “curious trio” are Scooby Doo-ish — a supposedly haunted castle, say, the “ghosts” of which are created by holographic projectors. But right from the beginning, there’s also a sci-fi aspect to the series: In the first story, Le Trio de l’étrange (The Curious Trio), while making a documentary about a river, the three friends are captured by a humanoid alien race, the Vineans… who are themselves at the mercy of their rogue central computer and security chief. Subsequent tales involve a destructive infrasonic instrument named the Devil’s Organ, a strange magnetic ore harvested by the Vineans, a corrupted artificial intelligence on the planet Vinea, a giant insectoid race, artificial tornadoes, and a giant lizard bred for a movie project. The Yoko Tsuno stories first appeared in Spirou magazine, and were originally drawn in the “Marcelline” style — think Franquin and Morris. Later, they were drawn in the Hergé-esque, schematic ligne claire style. Fun facts: Leloup worked in Hergé’s studio, creating detailed backgrounds and vehicles for The Calculus Affair, Flight 714 to Sydney, and other Tintin adventures. Later, while collaborating with the cartoonist Peyo on the series Jacky and Célestin, Leloup created a female Japanese female character who’d become the inspiration for Yoko Tsuno.

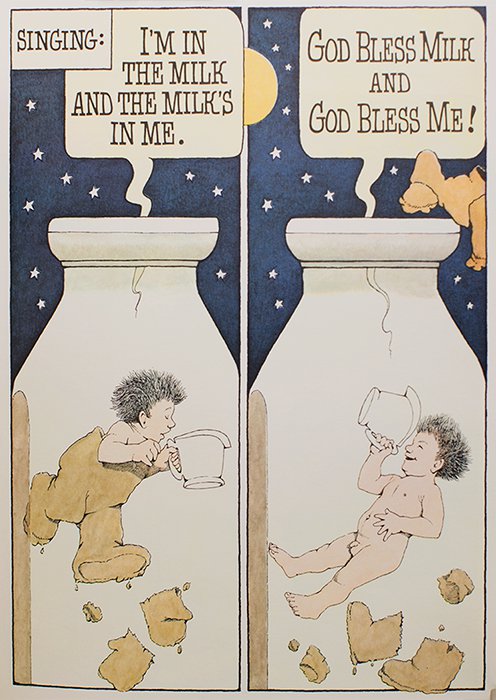

- Maurice Sendak’s children’s dream adventure In the Night Kitchen. A young boy named Mickey wakes up in the night, hearing a thumping sound coming from below his room. “Quiet down there!” he shouts — before falling out of his clothes and into the Night Kitchen, where enormous bakers (who look exactly like the silent-film comedian Oliver Hardy, though some commentators insist that they resemble Hitler) accidentally stir him into the batter for a cake and pop him into an oven. The artwork is miraculous: vintage-looking, with fond references to Winsor McCay’s early 20th-century strip Little Nemo In Slumberland, while also evoking Claes Oldenburg’s Pop Art “soft sculptures” of saggy hamburgers and baggy slices of cake. This is visual storytelling at its finest; as a child, I wanted to sink into the book’s oversized pages the way that Mickey sinks through the bedroom floor. Unlike Little Nemo, Mickey is an action hero — he isn’t at the mercy of his own subconscious. He pops out of the cake batter, shapes it into an airplane, and flies to the top of a skyscraper-like milk bottle towering over the Night Kitchen’s cityscape. Diving boldly into the milk, which dissolves his batter-jumpsuit, he delivers to the bakers the crucial ingredient they’d lacked for their cake. Then it’s back to bed. An empowering lucid dream, and a fine escapade. Fun facts: Sendak would later explain that Mickey’s escape from the oven is a reference to the Holocaust. Because of Mickey’s (innocent, exuberant) nudity, the book remains one of the most frequently challenged books in American libraries. Winner of the 1971 Caldecott Honor.

BEST SIXTIES YA & YYA: [Best YA & YYA Lit 1963] | Best YA & YYA Lit 1964 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1965 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1966 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1967 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1968 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1969 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1970 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1971 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1972 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1973. ALSO: Best YA Sci-Fi.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.