Listen, Hollywood! (9)

By:

September 21, 2019

One in a series of 10 posts suggesting novels (from Josh Glenn’s BEST ADVENTURES series) that really ought to be adapted for the big screen.

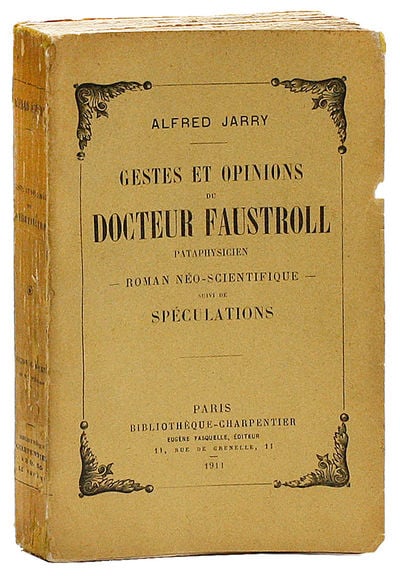

Alfred Jarry‘s picaresque adventure Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician: A Neo-Scientific Novel appeared on my list of the Best Adventures of 1911.

Elevator pitch:

The scientific method begins with precise observations of nature, conducted by a cautious researcher who has bracketed his imagination and blinkered his perspective; eventually, it results in a law or theory. Fuck that. Dr. Faustroll, a Paris-based scientist and inventor, instead practices a “science of imaginary solutions” which he dubs ’pataphysics. That is he to say, he embraces multiple perspectives, no matter how absurd they may seem — and recognizes no laws. The intrepid Faustroll flees his creditors in a high-tech amphibious “skiff” — accompanied by his Wookiee-like baboon-servant, Bosse-de-Nage; and also by Panmuphle, a tough repo man whom Faustroll has kidnapped and forced into service as a kind of galley slave. The trio embark upon a high-speed, slapstick, psychedelic metafictional odyssey which transports them from one bizarre fantasy island to another. This bawdy, high-lowbrow celebration of the imagination, artistic vision, and exploration — written by the infamous author of Ubu Roi — is the missing link between the myth of Jason and the Argonauts and New Wave sci-fi of the ’60s and ’70s! Why hasn’t it been adapted as a movie?

First act:

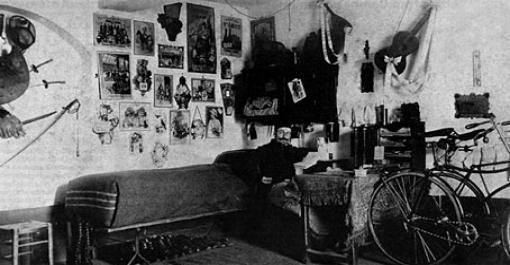

Meet Dr. Faustroll, whom one imagines resembling a time traveler from the future. He is smaller than his contemporaries; his hair and beard are startling; his skin-tight, space-suit-like costume is functional rather than decorative. He rides a bicycle everywhere, instead of driving. He fishes in the Seine for his dinner. Perhaps he carries a pistol.

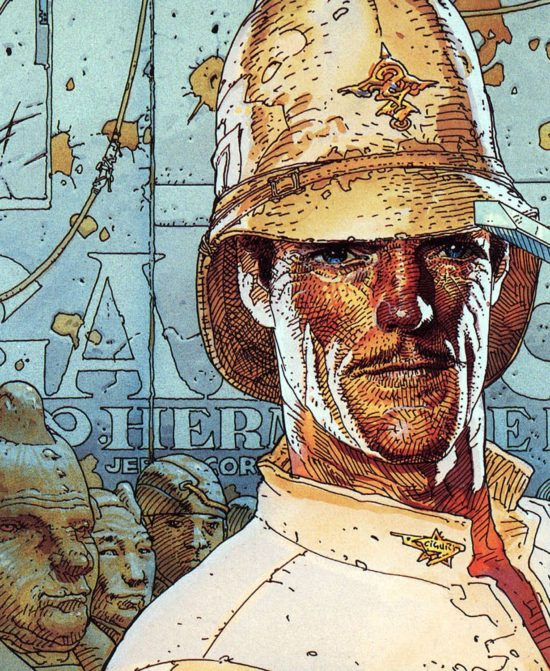

I’m describing Jarry himself, of course! Faustroll should be at least as eccentric in appearance — though note that he is every bit a scientist, and thoroughly rational. PS: Jarry describes Faustroll’s hair as alternately blond and black; his mustachios are green. He is a highbrow in a lowbrow’s body: He is muscular, virile, vigorous and athletic. When piloting his skiff, he wears an old-fashioned pith helmet — like Major Grubert’s, say.

Near the book’s end, we learn that Dr. Faustroll possesses a kind of philosopher’s stone — a ring that allows him to transmute matter. The ring works in conjunction with a stone set inside his skull — which can be observed through a clear watchglass window. So perhaps he really is some kind of cyborg or enhanced human from the future. Why is he here?

Faustroll’s crucial insight is that the virtual or imaginary nature of things as glimpsed by the heightened vision of far-out creative types, not to mention drug users, can be seized and lived as real. His scientific practice involves avidly pursuing such hypotheses; one imagines his laboratory as a shrine to the weirdest world-building of the moment: science fiction, fantasy, comic books, the discoveries of psychonauts and acid-freaks. Faustroll’s home laboratory is the site of many strange experiments — with soap bubbles, gyrostats, and so forth. It’s a playful, joyful, non-sterile space. It’s like the MIT Media Lab crossed with Sherlock Holmes’s home laboratory, as depicted in the Guy Ritchie movies. The fabric of reality is mutable — in motion — and Faustroll’s experiments are designed to allow him to perceive what he calls — borrowing the term from Vedic and Upanishadic texts — the Purusha, i.e., the unchanging and transcendent source of all that changes.

The only problem? Faustroll’s obsession with realizing the freaked-out fantasies of everyone from Coleridge, Mallarmé, and Beardsley to lesser-known poets and kooks has precluded his paying the rent on his laboratory for the past three years. Panmuphle, a debt collector sent to kick Faustroll out of his lodgings, winds up shanghaied aboard the skiff when the scientist takes flight.

The year — in Jarry’s novel — is 1898. However, as noted above, the movie could be set in almost any time period and major city. (The first question should be: What fictions do we want Faustroll to explore? Once we’ve answered this, we can set the action in London in the 1930s, New York in the 1950s, San Francisco in the 1970s, or…? If this were a TV series or trilogy of movies, one could choose all of the above.) Early on in the story, Faustroll’s home and laboratory are seized by Panmpuhple, who lists the books in the scientist’s collection: fantastical works by Poe, Bloy, Lautréamont, Rimbaud, Verlaine, and Jarry too. Each of these is a clue to the sort of adventure we’re about to embark upon.

Panmuphle shows up at the lab — not his first visit — to evict Faustroll once and for all. I imagine Panmuphle as tough, but not stupid; he’s a Jason Statham type, perhaps. Faustroll gets him drunk — in the novel, he hurls Panmuphle into a wine cellar whose barrels have all been breached — and into his skiff. He needs a man with Panmpuphle’s abilities….

Faustroll’s futuristic “skiff,” which can not only glide atop water but along streets and straight up walls, is capable of carrying passengers across the barriers of the imagination itself. Imagine the Millennium Falcon — jury rigged, perhaps, but awesome; the skiff is also an ancestor of the Heart of Gold — the prototype ship, in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, which uses the revolutionary Infinite Improbability Drive. To quote Karey Kirkpatrick, who with Douglas Adams adapted the novel for the screen in 2005, this ship is in fact a “plot contrivance machine”, making possible plotlines that would normally be too improbable to be believed. It’s cool and weird — visual references could include the Tardis, the Batmobile, Anakin’s podracer, and the Nautilus.

Faustroll explains the nature of his research, and the capacities of his vehicle, to Panmuphle. He also shows him evidence of his explorations — objects he’s managed to snatch from the fantastic realms he’s visited so far. For example, the ancient mariner’s crossbow, from Coleridge’s poem; the prince’s eyeball poked out by a horse’s tail in The Thousand and One Nights; a scarab from Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror; etcetera. For the movie’s purposes, these objects could derive from a different set of fictions: A Scanner Darkly, Lanark, V for Vendetta, Dhalgren….

The skiff’s other crewmember: Bosse-de-Nage is a hideous ape-like creature — his name means, more or less, “Buttocks Face” — who speaks in grunts only his master understands. He is a comical Chewbacca to Faustroll’s Han Solo (or Groot, say, to Faustroll’s Peter Quill). Bosse-de-Nage carries the skiff through a secret passageway and deposits it upon the pavement of a back street in Paris. Panmuphle is locked into position — he’s a kind of oarsman — and off they go! Visuals become foggy, and there is a pervasive tearing sound, as the skiff leaves behind quotidian reality for various invented worlds.

This is a revelatory and also hallucinatory, terrifying moment, for Panmuphle: He suddenly realizes that consensus reality is merely that which everyone has somehow consented to….

Second act:

In Jarry’s short novel about Faustroll, the skiff visits fourteen imaginary worlds. In some cases, Jarry is celebrating the imagination of artists or writers whom he admires; in other cases, he is mocking or criticizing someone’s world-building efforts. Each chapter is dedicated to the imaginative creator of this weird and wonderful, or terrible space.

The picaresque nature of Faustroll’s exploits allows this movie (or TV series) to switch between genres. Although all of the adventures have an absurd, comical edge, some of them are sci-fi, or fantasy, or horror, and so forth.

For example:

- The Isle of Cack — inspired by Louis L

- The Land of Lace — inspired by Aubrey Beardsley

- The Forest of Love — inspired by Emile Bernard

- The Amorphous Isle — inspired by Franc-Nohain; the inhabitants of this one reminds me of Iain M. Banks’s Minds: sapient, hyperintelligent machines originally built by biological species, which have evolved, redesigned themselves, and become many times more intelligent than their original creators.

- The Fragrant Isle — inspired by Paul Gauguin

- The Castle Errant — inspired by Gustave Kahn

- The Isle of Ptyx — inspired by Mallarmé. Here, one can perceive the true substance of the universe, unmediated.

- The Isle of Cyril — inspired by Marcel Schwob’s Imaginary Lives, a collection of semi-biographical short stories mixing known and fantastical elements. Here we encounter Captain Kidd — or Schwabb’s version of Kidd.

- The Great Church of Snoutfigs — inspired by Laurent Tailhade. A Cthulhu-like horror show, involving a monster conjured up during a church service.

These are amusing interludes, but today’s reader (or moviegoer) will have no clue what’s being celebrated and/or mocked. So it will be important that this movie send Jarry and his intrepid crew to islands evoking contemporary literature and entertainments.

For example:

- The Isle of Ironic Gore — inspired by Q. Tarantino

- The Isle of Nested Irreality — inspired by C. Nolan

- The Isle of Unpacked Identities — inspired by Z. Smith

- The Isle of Brain-Splittery — inspired by S. Jonze

- The Isle of Subverted Fairytales — inspired by H. Oyeyemi

- The Isle of Woke Horror — inspired by J. Peele

- The Isle of Lost Illusions — inspired by J. Offill

- The Isle of American Middle-ness — inspired by J. Franzen

- The Isle of Loathsome Wit — inspired by M. Houellebecq

One could have a great deal of fun mapping out this meta-fictional voyage extraordinaire.

Third act:

In Jarry’s novel, a third character now joins us. A merman, of sorts: Bishop Mendacious. This is “the Sea Bishop,” a marine monster in a bishop’s habit spotted in Poland in 1531; one pictures a malignant, religiously garbed version of Mike Mignola’s Abe Sapien. (Sapien began his life as Caul, a Victorian scientist who became involved with the Oannes Society, an occult organization who believed in life and all knowledge having come from the sea. After retrieving a jellyfish-like deity from an underwater ruin, Caul and the other members performed an arcane ritual that inadvertently ended with the creature’s release and Caul being turned into a merman.)

We also learn that Faustroll becomes uncontrollably murderous when he sees an image of a horse’s head.

Bishop Mendacious reveals a horse-head sign to Faustroll, who winds up releasing a poisonous fog in Paris — and killing Bosse-de-Nage.

Here is where I’d strongly suggest deviating from Jarry’s original text. In fact, at this point in the story, Jarry seems to have given up on his original plan. There is an extended sequence in which the Bishop encounters a kind of Weeble — a man-shaped toilet paper holder, that rocks back and forth on a hemispherical based — and throws it down the toilet, then shits on top of it. Why?

Bosse-de-Nage then reappears — somehow, he isn’t dead. Faustroll sets some sort of monstrous automatic painting machine into motion. Kinda like Damien Hirst’s “spin painting” device, only this one occasionally creates great works of art. Faustroll sleeps with the Bishop’s daughter.

There’s a kind of apocalyptic ending. Faustroll and Panmuphle die — but they don’t really die. They dissolve into what Faustroll calls “Aethernity” — one thinks of the Force.

While a traditional happy ending would be pointless, I’m not sure that the movie needs to devolve into pure toilet humor or mysticism. Let’s have a think about this.

Hollywood, this is one of the great absurdist adventures. Before Dr. Strangelove, Delicatessen, Monty Python’s Life of Brian, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, Zelig, The Jerk, Blazing Saddles, Synecdoche, New York, The Exterminating Angel, Birdman, Eraserhead, Brazil, or The Lobster, to name a few great absurdist movies, there was Dr. Faustroll. Let’s do this!

LISTEN, HOLLYWOOD: Michael Innes’s FROM LONDON FAR | P.G. Wodehouse’s LEAVE IT TO PSMITH | Peter Dickinson’s CHANGES TRILOGY | Robert Heinlein’s GLORY ROAD | Poul Anderson’s THE HIGH CRUSADE | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s TARZAN AND THE FOREIGN LEGION | G.K. Chesterton’s THE NAPOLEON OF NOTTING HILL | Michael Innes’s THE JOURNEYING BOY | Alfred Jarry’s EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN | André Gide’s THE VATICAN CAVES [LAFCADIO’S ADVENTURES].

Also see Josh Glenn’s SHOCKING BLOCKING series: It Happened One Night (1934) | The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) | The Guv’nor (1935) | The 39 Steps (1935) | Young and Innocent (1937) | The Lady Vanishes (1938) | Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) | The Big Sleep (1939) | The Little Princess (1939) | Gone With the Wind (1939) | His Girl Friday (1940) | The Diary of a Chambermaid (1946) | The Asphalt Jungle (1950) | The African Queen (1951) | A Bucket of Blood (1959) | Beach Party (1963) | For Those Who Think Young (1964) | Thunderball (1965) | Clambake (1967) | Bonnie and Clyde (1967) | Madigan (1968) | Wild in the Streets (1968) | Barbarella (1968) | Harold and Maude (1971) | The Mack (1973) | The Long Goodbye (1973) | Les Valseuses (1974) | Eraserhead (1976) | The Bad News Bears (1976) | Breaking Away (1979) | Rock’n’Roll High School (1979) | Escape from Alcatraz (1979) | Apocalypse Now (1979) | Caddyshack (1980) | Stripes (1981) | Blade Runner (1982) | Tender Mercies (1983) | Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life (1983) | Repo Man (1984) | Buckaroo Banzai (1984) | Raising Arizona (1987) | RoboCop (1987) | Goodfellas (1990) | Candyman (1992) | Dazed and Confused (1993) | Pulp Fiction (1994) | The Fifth Element (1997) | Nacho Libre (2006) | District 9 (2009).

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.