10 Best Adventures of 1954

By:

September 15, 2019

Sixty-five years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Nineteen-Fifties (1954–1963) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- J.R.R. Tolkien‘s fantasy adventure The Lord of the Rings (w. 1937–1949, p. 1954–1955). Frodo Baggins, an unassuming hobbit, inherits a magical ring from his uncle, Bilbo; their wizard friend, Gandalf, discovers that it’s none other than the One Ring, forged by the Dark Lord Sauron thousands of years ago, and used to corrupt and control the elves, dwarves, and men who wore subsidiary rings of power. Accompanied by his loyal friends Sam, Merry, and Pippin, Frodo carries this terrible artifact to Elrond, one of the most powerful elves remaining in Middle Earth; en route, the hobbits are aided by the immortal Tom Bombadil, and by a mysterious and grim Ranger, Aragorn. Though Frodo is badly wounded by Sauron’s Black Riders, who are on the trail of the ring, the hobbits attend the Council of Elrond. It is decided that the ring must be destroyed by casting it into the fire of Mount Doom, in Sauron’s far-off and foreboding stronghold, Mordor; Frodo reluctantly but courageously volunteers to carry the ring. Accompanying him are his hobbit friends, Aragorn, Gandalf, Gimli the Dwarf, Legolas the Elf, and the human warrior Boromir. Forced to take a perilous path through the Mines of Moria, they are attacked by a host of orcs and an ancient demon; meanwhile, Boromir begins to desire the ring for himself — so Frodo decides to flee the fellowship. Orcs capture Merry and Pippin, and Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas pursue them. Gandalf rouses the King of Rohan to ride to the ancient fortress of Helm’s Deep; tree-people known as Ents lead an attack on the stronghold of a turncoat wizard; Gollum, a twisted hobbit-creature whom we’ve met before, guides Frodo and Sam via secret paths to Mordor… but leads them into the lair of a giant spider. Epic! I’ve written about The Return of the King, the rousing final volume of The Lord of the Rings, elsewhere. Fun facts: This three-part book, which began as a sequel to Tolkien’s 1937 fantasy novel The Hobbit, was the final movement of a larger epic on which the author had worked since 1917; it is probably the most influential work of fantasy of the 20th century. Half of the book was adapted by Ralph Bakshi as a creepy animated movie in 1978; it is now a cult classic. Peter Jackson’s live action adaptations (2001–2003) were a box-office smash.

- Rosemary Sutcliff’s YA Eagle of the Ninth historical adventure The Eagle of the Ninth. The story is set in Roman Britain in the early 2nd century AD. Some years earlier, the Ninth Legion of the Roman Army had marched into northern Britain, bearing a bronze eagle as their standard; they were never seen again. (Sutcliff was inspired to write the story by the disappearance of the Ninth Legion from the historical record following an expedition north to deal with Caledonian tribes in 117.) The son of the Ninth Legion’s commander, Marcus Aquila, who’s grown up to be a soldier, is discharged from the military after being wounded in battle. While recuperating, he forms friendships with Esca, a young Briton whom Marcus purchased as a manservant-slave, an orphaned wolf cub, and Cottia, a British girl being raised as a Roman. Marcus dreams of discovering the truth about the disappearance of the Ninth Legion, and restoring his father’s honor; finally, accompanied by Esca, he disguises himself as a Greek oculist and travels beyond Hadrian’s Wall into Caledonian territory. There, he learns that the titular eagle of the ninth has become a symbol of Roman defeat among the restive tribes along the border. Can he retrieve it? Sutcliff’s writing is gorgeous, the action is thrilling, and we come to care deeply about Marcus and his friends. Fun facts: The Eagle of the Ninth is the first in a sequence of novels tracing the history of a family, of the Roman Empire and then of Britain; these include — in series order — The Silver Branch (1957), The Lantern Bearers (1959), and Sword at Sunset (1963). A 2011 movie adaptation starred Channing Tatum as Marcus Aquila and Jamie Bell as Esca.

- Richard Matheson’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure I Am Legend (1954). Though it has inspired more thrilling novels (Stephen King is a Matheson fan) and movies, I Am Legend is less an adventure than it is a novel of ideas (about the psychology of social isolation), a bleak Robinsonade (set in a vampire-infested Los Angeles of 1976, with no hope of rescue), and a scientific mystery (valorizing painstaking inductive reasoning). What action there is largely occurs in flashbacks — as we learn about the devastating spread of a zombie-ism/vampirism-like pandemic. Even our hero, Robert Neville, is less creative and brilliant than he is merely dogged; and he’s a drunk. Still, there is much to enjoy here. Neville stakes vampires by day, and by night — as the vampires howl outside his door — he attempts to unravel the cause of the plague (are the vampires physically, or just psychologically transformed?), and muses about the overlap between legend and history. Then he meets — and pursues, and captures — Ruth, who might be a survivor of the plague. Or is she something else? Are there non-feral vampires? Is he, himself, a legend? Fun fact: The excellent 1971 science-fiction movie The Omega Man, starring Charlton Heston, is loosely based on I Am Legend. Other movie adaptations have been less entertaining.

- Agatha Christie’s espionage adventure Destination Unknown (US title: So Many Steps to Death. Just before she overdoses on sleeping pills in a Moroccan hotel, Hilary Craven is approached by Jessop, a British secret agent who talks her out of killing herself… and persuades her to instead undertake a dangerous mission, impersonating the wife of a young boffin who’s invented ZE Fusion — and who may have defected to the Soviets. The scientist’s wife was apparently en route to a rendezvous with her husband when her plane to Casablanca crashed; she won’t live long. Hilary’s daughter has died, and her husband has left her — so why not, she figures. Heading to a secret scientific research facility in the Atlas Mountains, which is disguised as a medical research center, she meets a Hitchcockian-esque assortment of characters, none of whom can be trusted to actually be who they claim to be. (One of them, a handsome young American, is particularly compelling.) Hilary’s putative husband is indeed at the facility — which turns out not to be a Soviet operation, after all. With the help of clues that Hilary has left behind, Jessop pursues her to the facility. An ingenious escape plan is concocted, but is it too late? Destination Unknown asks us to grapple with questions — is pure scientific research immoral, if it could lead to death and destruction? should the younger generation use its energy to overthrow accumulated wealth and prestige? — less vexing, perhaps, to earlier and later readers. I prefer the absurdity of Michael Innes’s Operation Pax (1951), but this is fun stuff. Fun facts: Christie was writing in the wake of the Fuchs/Pontecorvo affairs. In 1950, Klaus Fuchs, a German theoretical physicist who’d worked on the Manhattan Project during WWII, was arrested for espionage; it seems he’d been supplying information to the Soviet Union. Bruno Pontecorvo, an Italian nuclear physicist who’d worked with Fuchs after the war at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment in Harwell, England, defected to the Soviet Union that same year.

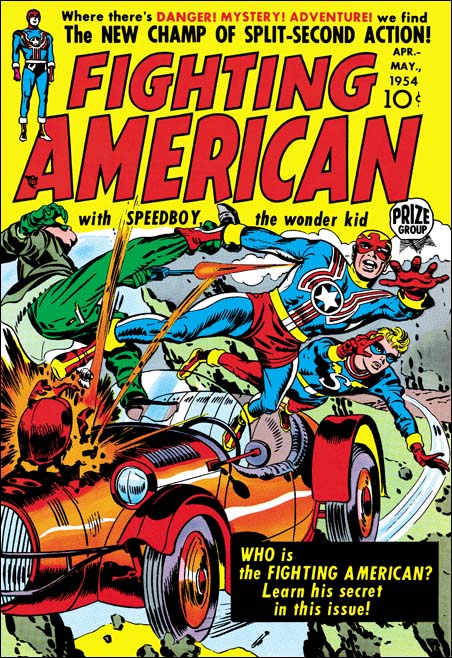

- Joe Simon and Jack Kirby‘s Fighting American comic (1954–1955). When Joe Simon and Jack Kirby created Fighting American, first published by Prize Publications, they did so as a gag; note that Harvey Kurtzman and Wally Wood‘s “Superduperman” had appeared in MAD Magazine the previous year. What makes this comic so interesting and enjoyable to read is the fact that Simon and Kirby were parodying their own creation. Back in 1941, they’d introduced Captain America to the American public with a first-issue cover on which the titular patriotic supersoldier punches Hitler in the face. Captain America, which became a best-selling title for Timely (eventually, Marvel), helped revolutionize the comic-book layout with dynamic action splashed across full and sometimes double pages. In the years following WWII, Simon and Kirby’s studio would crank out all sorts of titles — romance, crime, western, sci-fi, war — but superhero comics were on the wane. Fighting American is an absurdist effort: Our hero’s alter ego is Johnny Flag, a McCarthy-esque TV commentator who denounces Communist supporters; weirdly, his true identity is the unathletic younger brother of the dead Johnny. His enemies have monikers like Poison Ivan, Deadly Dolittle, Invisible Irving, and the Sneak Of Araby; his sidekick is Speedboy. But the action is truly spectacular — much more so than Simon and Kirby’s work on Captain America. It’s as though the pioneering comics duo was demonstrating what superhero comics could become; in 1961–1963, when Kirby and Stan Lee co-created The Fantastic Four, The Avengers, et al., everybody else finally got the message. Fun facts: In 1966, Simon packaged a single issue of Fighting American consisting of reprints and unpublished material, for Harvey Comics. The 2010 collection Simon and Kirby: Superheroes, a gorgeous doorstopper from Titan Books, is probably the best source for Fighting American‘s original run.

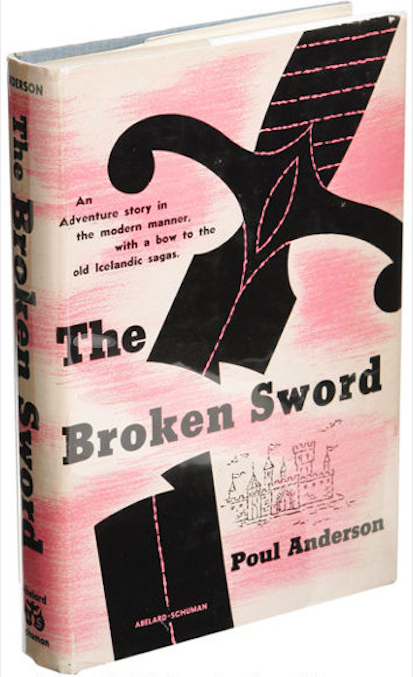

- Poul Anderson’s fantasy adventure The Broken Sword. In the 11th century, when the Danes held sway over northern and eastern England, but the “White Christ” as the Vikings called Jesus) was threatening the power of the Norse, English, and Irish gods, Skafloc, son of the half-Christian Viking chieftan Orm the Strong, is kidnapped and raised by elves; in his place, the elves leave a troll-born changeling called Valgard. Alfheim, homeland of the elves, trolls, sprites, sidhe, goblins, etc., is everywhere apparent… but as Christianity spreads, Alfheim is diminishing, vanishing. Meanwhile, a troll army is massing to destroy Alfheim forever. The Norse gods, engaged in a war with the Frost Giants, set the story in motion thanks to their strategic maneuvers. Skafloc, who grows up to be a warrior and wielder of elf magic, is presented with a broken iron sword; a gift of the Norse gods, it can only be repaired by the frost giant Bolverk. Valgard, meanwhile, grows up to be a brutish Viking berserker; when he discovers the truth of his own origins, he joins the trolls. Anderson, whose Hrolf Kraki’s Saga (1973) would retell Danish sagas, remains true to Norse stories of heroic achievement: the action is brutal, everybody loses. Fun facts: Reviewers of The Broken Sword often note the similarities between its plot and that of The Lord of the Rings, published the same year. Both Anderson and Tolkien mined “the Northern thing” as they developed their own modern versions of epic fantasy; Anderson’s version was less hopeful, and less successful. Michael Moorcock declared The Broken Sword the superior effort, and noted its influence on his Elric saga.

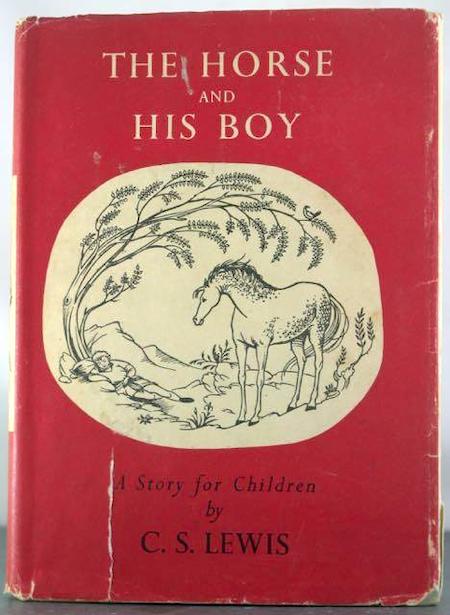

- C.S. Lewis’s Narnia fantasy adventure The Horse and His Boy. During the reign of the four Pevensie children as kings and queens of Narnia, two Narnian talking horses, Bree and Hwin, both of whom were stolen by the Calormenes as foals, escape from Calormen — a Middle Eastern-esque country to the southeast of Narnia, and separated from it by the country of Archenland and a large desert — and head home. Riding Bree is an orphan named Shasta, who wants to avoid being sold into slavery; riding Hwin is Aravis, a young Calormene aristocrat, who is running away to avoid being forced to marry Calormen’s vizier. The group passes through Calormen’s capital city, Tashbaan, where they learn of the ruler’s plan to invade Archenland and raid Narnia; they also encounter Narnian visitors who mistake Shasta for an Archenland prince to whom he bears a striking resemblance. They flee into the desert, heading for “Narnia and the North!” Along the way, they encounter vicissitudes which turn out to have been blessings in disguise orchestrated by Aslan; this is Lewis’s religious message. Will they warn Archenland of the invasion in time? And will Shasta discover his true identity? Fun facts: Of the seven novels that comprise The Chronicles of Narnia (1950–1956), The Horse and His Boy was the fourth to be written and the fifth to be published; according to the series’ internal chronology, however, it is the third book. It’s the only series installment to take place entirely within Narnia.

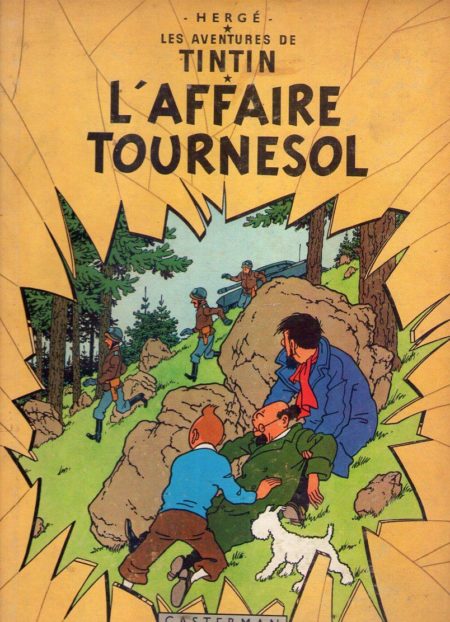

- Hergé’s Tintin adventure L’Affaire Tournesol (The Calculus Affair, 1954–56; as an album, 1956). Glass and porcelain items at Marlinspike Hall begin to shatter inexplicably; the next day, Professor Calculus leaves for Geneva to attend a scientific conference. Tintin and Haddock follow him there, only to be run off the road into Lake Geneva… then nearly blown up! We discover that intelligence agents from Syldavia and Borduria — the fictional Balkan nations we’ve already visited in King Ottokar’s Sceptre and Destination Moon — are seeking to obtain an ultrasonic device, capable of being used as a weapon of mass destruction, which Calculus has recently developed. This is espionage thriller along the lines of Ambler’s The Dark Frontier or Cause for Alarm, say, or — closer to home — Edgar P. Jacobs’s Blake and Mortimer comic Le Secret de l’Espadon (1946–1949), and it’s a fun ride. Tintin and Haddock remain one step behind as Calculus is kidnapped by first Bordurians, then Slydavians, then Bordurians again; when they arrive in Borduria’s capital, Szohôd, they’re monitored by Colonel Sponsz’s secret police. Meanwhile, back in Marlinspike, for comic relief, insurance agent Jolyon Wagg and his family move in for a holiday. Will Tintin and Haddock rescue Calculus, and get him home? Fun facts: The 18th Tintin adventure was serialized in Belgium’s Tintin magazine. Hergé’s depiction of Borduria was based on Eastern Bloc countries; Hergé named the country’s leader Plekszy-Gladz, a pun on Plexiglas, although the comic’s English translators renamed him Kûrvi-Tasch, a mustache joke.

- Jack Finney’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure The Body Snatchers (1954; as a book, 1955). Why, wonders psychologist Miles Bennell, are so many of his patients — in bucolic Mill Valley, California — suddenly convinced that their loved ones aren’t really who they’re supposed to be? These doppelgängers, according to their spouses, relatives, colleagues, and friends, look exactly like the people they’ve replaced; they share their victims’ memories and mannerisms. But they’re not them! A case of mass hysteria, Bennell decides… until he discovers a curiously “blank” body, without features or fingerprints, concealed in a basement cupboard. He and his ex-girlfriend, along with others convinced that something uncanny is going on, begin to wonder whether there is an alien invasion going on. And if so, who can they trust? The aliens — and the science behind how they operate — aren’t particularly believable… but the dramatic tension is incredible. How much evidence of the impossible is required until we see the truth? Fun fact: Serialized in Colliers in 1954. (Philip K. Dick’s pod-people story, “The Father-thing,” was published a few months later.) Memorably adapted as a movie in 1956, by director Don Siegel; and again in 1978, by director Philip Kaufman — with an extraordinary cast that includes Donald Sutherland, Brooke Adams, Veronica Cartwright, Jeff Goldblum, and Leonard Nimoy.

- William Golding’s sardonic Robinsonade Lord of the Flies. In the midst of a wartime evacuation, a British airplane carrying boys in their middle childhood or preadolescence crashes near an uninhabited island in a remote region of the Pacific. Ralph and an overweight, bespectacled boy nicknamed “Piggy” convene all the survivors; among them are the members of a boys’ choir, led by the red-headed Jack. Ralph establishes a policy of having fun, surviving, and maintaining a smoke signal that could alert passing ships to their presence; Jack, whose choirboys become the group’s hunters, and a semi-epileptic boy named Simon become Ralph’s lieutenants. Poor Piggy, whose glasses are used to start a fire, becomes a laughing-stock. When Jack lures the signal fire crew away for a hunt, a ship passes the island without rescuing them; this leads to a rift between Ralph and Jack. Meanwhile, when Simon encounters a pig’s head that the hunters have mounted on a stake, he conducts an imaginary dialogue with the “Lord of the Flies,” which warns him that the increasingly savage hunters and their breakaway tribe will kill him. Things rapidly get worse, and soon Ralph is fleeing for his life through the forest, worried that his own head will end up on a stake! Fun facts: Lord of the Flies, Golding’s first novel, which is to the 1858 young castaway’s novel The Coral Island what The Borribles is to Elisabeth Beresford’s Wombles books, became a bestseller — and has been called one of the best English-language novels of all time. It has been adapted more than once for the screen, but never successfully.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.