STUFFED (37)

By:

August 31, 2019

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste. STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s collection of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

A thousand years ago it was hip to put piles of expensive spices in your dishes, a way of expressing that you were at the center of the grand caravan of goods traveling around the world, and not just some beer soup-eating ding-dong.

In ancient Rome, you were judged by the sophistication of the garum in your larder. Aulus Umbricius Scaurus, the Pompeiian garum mogul, made versions for various tastes and budgets, for example, and dispensed them in branded amphorae. In the 17th century, wars were fought over the islands where cloves were grown, and the British East India company drew ton after ton of turmeric out of Indian soil. In the 19th century, the first product marketed around the globe was Worcestershire sauce; bundled up and taken on early cruises and then handed or sold out by the ship’s steward at the end of the voyage. Now it waits in your refrigerator to be dispensed in sad shakes into Bloody Marys, soups, meat stew — or maybe you use it all the time, I don’t know your life. The point is, it’s there, along with some standards: ketchup, mustard, four hot sauces (only one of which you use), barbecue sauce, taco sauce, HP Sauce in case your anglophile cousin Jerry visits again, a pot of Tewkesbury mustard that Jerry left last visit, a few odds and ends.

These are clutter, yes — dumb purchases, vague intentions, dishes made once and discarded now just a condimental synechdoche. But they also form a counterweight to the long-ago ravages of the spice trade, an egalitarian balance made up of squeeze bottles and funny little jars. The profusion of 20th century condiments in the US means that while we may not have saffron, whole nutmeg, cardamom, and vanilla beans laying around, even after all these years, we do have 14 jars of things that seemed like a good idea at the time. The unifying element to all of these condiments? The sloppy joe.

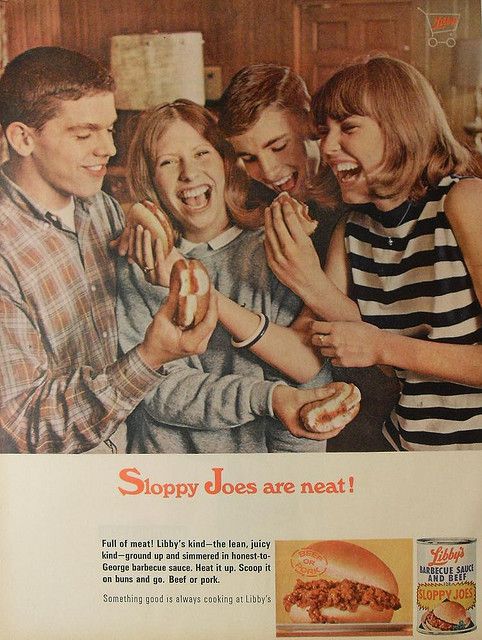

The sloppy joe injects some order into our cluttered refrigerator doors: this array of purchases, good, bad, and indifferent, suddenly can make a sort of sense. At least, until Manwich came out in 1969 and buggered the whole dream.

For decades, sloppy joes were a muddled memory of things we have eaten recently, or thought we might eat — or not even that, the things that we meant to put on the things we were going to eat, but maybe didn’t. At least I always thought that’s what they were meant to be — assembled yourself from these condiments both loved and unloved, whatever you found in your refrigerator was fair game for mixing together with that meat (fresh, freezer grey, or in between), into a riotous bouquet. Sure you’d screw it up now and again, have to sweep your mistakes under the rug with extra worcestershire and ketchup, but it was your mess, at least, where you could stage your own condiment triumphs and catastrophes within the broad confines of what constitutes a sloppy joe: ground meat, tomato sauce of some sort, spices.

If condiments are how we express our freedom as we eat, free from the tyranny of restaurants, then sloppy joes are an ecstatic version of that, an outpouring; messy, ocasionally stupid, overwrought and ill advised, but often delicious. Just like America.

At first blush, sloppy joes do seem like the most American thing this side of baroque jello salads, and there are reasons it emerged as such an American, and 20th-century, phenomenon. For centuries, most ground meat (it took awhile for technology to make grinding meat an industrial-scale affair) found its way into sausages, especially across the Atlantic. For example, Hannah Glasse had a couple recipes in her famous 1747 cookbook: Hamburgh Sausages (minced beef, pepper, cloves, nutmeg, a great quantity of garlic, vinegar, salt, red wine, rum stuffed into a casing) and another for a similar mixture stuffed inside a turkey and roasted (nice one, Hannah Glasse, using a turkey as a sausage casing). If it wasn’t sausage, most ground meat ended up as a meatball or in a pie, leaving the bulk of free ground meats for America.

Around the country there are parallel sandwiches to sloppy joes, especially in the midwest where they specialize in a dry variety grouped (notice I won’t say loosely) under the “loose meat” moniker. Bunched up together, they include sandwiches called: Loose meat, “rubble”, maid-rite, tavern sandwich, barbecue, dynamite, hot tamale, yip yip, slush burger, steamer and wimpie. Adjacent to loosemeat and sloppy joe style sandwiches are similar but not quite identical varieties like the chop cheese of the Bronx (lacking some of the meat spices but adding cheese and panache), and Cincinnati chilli (noodles in lieu of a bun — or, in even more pleasing fashion, used as a condiment itself). Loose meat sandwiches are traced to Sioux City, Iowa in the 1920s (some try to trace sloppy joes there as well, even though they were never popular there as near as anyone can tell). Loose meat sandwiches are sloppy joes’s more earnest cousin — a little less crazy, delicious maybe, but cautious, sensible: it’s surprising they didn’t catch on in New England. Because you can’t really can the ingredients of loose meat, they were never aggressively co-opted — though there is still a small chain of loose meat restaurants called Maid-Rite founded in 1926 with 33 restaurants across the midwest.

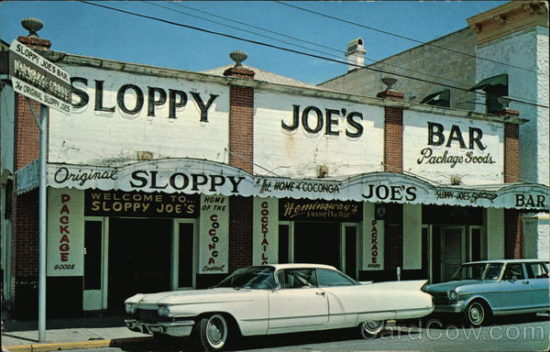

Sloppy Joes, on the other hand, are traced to the eponymous restaurant in Key West which opened in 1933. Before that, Jose Abeal Otero ran the original Sloppy Joe’s in Havana from around 1917 until it closed following the revolution in 1959. They served a sandwich, a sort of regular man’s mash-up of ropa vieja and picadillo on a bun, that was quite popular and carried the bar’s name with it when it washed ashore in the U.S. The Key West bar, originally called the Silver Slipper, was changed to Sloppy Joe’s, the story goes, at the urging of Ernest Hemingway, in honor of his favorite Havana joint — and it’s no effort to imagine Ern drinking mojitos and socking away a half dozen or so sloppy joes. Hemingway famously called Key West “the St. Tropez of the poor,” so his part in importing the sloppy joe there is certainly on point.

Like the regional sandwiches, ropa vieja and picadillo vary, but typically contain onions, garlic, tomato, spices and, sometimes for ropa vieja and generally for picadillo, raisins, and capers or olives. Ropa vieja is made with ragged strips of flank steak (thus the name – old clothes), picadillo with ground meat (usually beef). Simplified slightly, Worcestershire instead of capers or olives, for example, it’s basically a sloppy joe. But no one would have been bothered in the ’30s, ’40s, or ’50s that a widespread American sandwich, and one that was enlivened by proletarian sensibilities commingled with democratic ideals, originated in Cuba. It wasn’t until the revolution that the sloppy joe would have even begun to attract scrutiny.

The original Sloppy Joe’s closed right after the end of the Cuban revolution and the Cuban people, who presumably had other things on their mind, lost touch with the sloppy joe sandwich. But in the U.S. it gained in popularity, becoming a staple of home cooking — through the ’60s it appeared frequently in community cookbooks and on school lunch menus, but by the end of the decade it had attracted the attention of Norton Simon, a major player in both the food and media businesses. Simon had made a fortune with Val Vita foods and merged it with Hunts in 1943. Purchasing undervalued businesses post WWII, he eventually rolled them up with Wesson-Snowdrift, Canada Dry and McCall’s Publishing into Norton Simon Inc. in 1968. The following year, Hunts launched Manwich brand sloppy joe sauce.

All of a sudden, Hunts was bumped up against the publishing world —which at the time was a hotbed of mind control and CIA operations both obvious and clandestine. California, where most of these businesses were located and founded, was itself a weird vortex of CIA ops and public opinion manipulation. UCLA had, also in 1969, just lured Louis Jolyon West to be head of their psychiatry department. West had been at the University of Oklahoma where he worked with the CIA on MK-Ultra and became infamous for overdosing an elephant with LSD to see if he could make it more tractable. Norton Simon board member Franklin Murphy, already well known for his work with the CIA, was chancellor of UCLA from 1960–68 and still has buildings there named after him. So did the CIA create Manwich to commodify this freewheeling cuban sandwich? Impossible to say, but certainly, this was the sort of thing that they did routinely. After all, they had recruited Gloria Steinem in the 1950s to work for their Independent Research Service which sought to disrupt leftist youth festivals. Many of Steinem’s early feminist articles were published by Independent Research Service associated persons (notable Clay Felker) and when she was named McCall’s Woman of the Year in 1971 it declared that the feminist movement was now in “Phase II” and that “radicals were necessary for getting the thing started … but the ‘moderates’ were now in control.”

There was a great deal of CIA money and ideas floating around publishing, advertising and marketing in these years, some of it guiding, some pushing, and some shoving things into an order that they preferred. So many people were in bed with the CIA in some fashion that you could assume lots of things were influenced by the CIA, and maybe you should. Whether it was the CIA, the industrial marketing machine, or the invisible hand of the condiment-hating prepared meals sector (and who is to say they aren’t all the same people?), it happened.

In any case, sloppy joes began in 1969 on the path they remain on today: codified, trapped in a can and defined by their confinement. They live on, but sadly. While in the decades previous to the 1970s recipes show up regularly in fundraiser cookbooks, magazine and newspaper stories, in the decades after, it is mostly ideas for school cafeteria lunches and strategies for slipping in some textured vegetable protein. Someone had succeeded in hobbling the great sloppy joe. And it limps on still. But if everyone of you will go to your refrigerator now and then and look around, pick a few ingredients that speak to you (making sure one is tomato-based), and slam them together, we might be able to bring the sloppy joe back as it once was: brave and sloppy and free.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.