PLANET OF PERIL (41)

By:

August 23, 2019

One in a series of posts, about forgotten fads and figures, by historian and HILOBROW friend Lynn Peril.

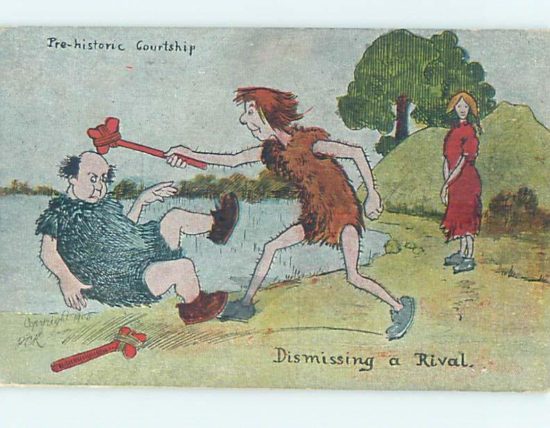

Los Angeles Times columnist Timothy Turner tried, though not very hard, to root out the beginning of the caveman meme in 1958. A caveman dragging a woman by the hair was “a cartoonist’s formula for a laugh, and not a bad one all things considered,” he wrote, noting that The New Yorker had recently run just such a cartoon. He thought the first such drawing was in an 1890s issue of the humor magazines Puck or Judge — he forgot which.

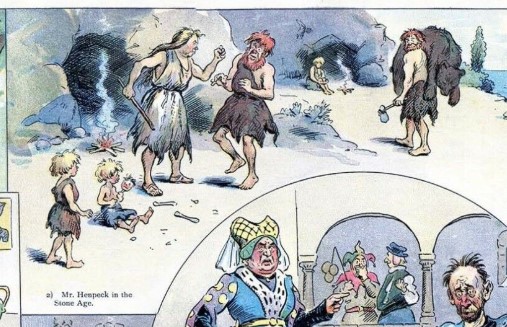

There is an 1897 cartoon in Puck that showed a paleolithic “Mr. Henpeck,” but he wasn’t dragging anyone by the hair, let alone his angry, club-wielding wife. An even earlier text reference comes from “The Romance of the First Radical,” Andrew Lang’s 1886 story set “shortly after the close of the last glacial epoch in Europe,” when “ladies who had been knocked on the head” were “dragged home, according to the marriage customs of the period.”

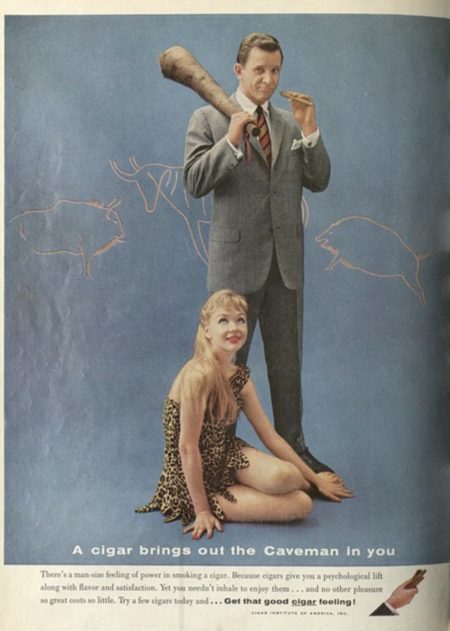

Via words or images, the caveman meme spread rapidly in the decades before and after the turn of the 20th century, probably because it struck a nerve. Gender roles were rapidly changing. The office was replacing the farm as the place most men worked. Was the modern businessman too effeminate? Did modern women yearn for a brute in the bedroom? Xenophobia was rampant as immigrants from Ireland, Italy, and Eastern Europe poured into the country. Were these “primitive” people more inclined to criminality than WASP-y American citizens?

A 1906 editorial in a New Jersey newspaper posited that the “average woman” couldn’t understand why business was more important to a “real man” than love. This made modern woman “inferior” to her Stone Age counterpart. “The caveman, after he had knocked the woman on the head whom he chose to swing over his shoulder and take home with him to do his housekeeping, brought to her the trophies of the chase, the treasures of the wood and stream,” and she appreciated them. She didn’t need him to tell her “that she had eyes like an antelope, and a throat like the swan on a dim woodland lake.” Poppycock!

Newspapers frequently used the term “cave man methods” to describe the abduction of a woman, with or without her consent, by a man who intended to marry her. The fall and early winter of 1912 saw a rash of such occurrences. On October 4, a fifteen-year-old girl in Detroit was “bound and partially gagged” by a “lovesick swain,” i.e., a boyfriend to whom her father objected. The police took the couple into custody after the boy pulled a gun on a taxi driver who refused to drive them after sizing up the situation. The newspaper quoted the girl’s mother in pidgin English. “You letta him go,” she told the cops. “He only want to marry my girl. He no hurt Rosa.” They were released. In their immigrant neighborhood, it was “considered a feather in the cap of a family to have one’s daughter taken from the home by cave man methods,” explained the newspaper.

On the 25th, Dominick Provenzano of Chicago used “cave man methods to drag away” 17-year-old Santa Lonandola. Her mother did not approve of him, so he “clapped his hand over the young woman’s mouth” and carried her off, aided by his brother-in-law. The two men drew revolvers and a knife when the crowd tried to stop them. At the police station, the young woman and her abductor demanded to be married at once, but the Dominick didn’t have a marriage license. The cops decided to postpone the matter until the girl’s father returned from a railway camp.

In December, “five Italians” entered the Detroit household of Pietra Pallazola, tied and gagged both Pietra and her sister, then left with Pietra. According to the sister, the mastermind was a man she knew only as Francesco. “When he became convinced his dream of happiness was not to be, if the decision was left to the girl,” he got a marriage license and enlisted his friends to assist in kidnapping her.

Perhaps not coincidentally, 1912 was the year D.W. Griffith’s silent film Man’s Genesis hit nickelodeon screens. In it, a pair of outrageously mugging cavemen, Weak-hands and Brute Force, compete for the love of Lillywhite (subtlety wasn’t a strong point). Caveman pop culture likely didn’t inspire the events in Chicago and Detroit, but it may have given newspaper reporters a way to frame the abductions as those of “primitive” immigrant culture.

Cave-man methods, as deployed by upper-crust WASPs, were at the heart of The Misleading Lady, a Broadway hit of 1913 described by the New York Times as “a crazy quilt of fun, surprise, and thrills.” In order to convince the producer of a play that she is right for the role of a siren, Helen Steele bets that she can get a man to propose to her during a long weekend at a country house. She picks “the wrong man for the experiment.” Jack Craigen is “a dominant, fearless gentleman, recently returned from Patagonia, who has definite theories about womankind that he isn’t afraid to put into practice.” He nevertheless falls for Helen’s ruse and proposes, only to be greeted by laughter from the producer and other guests. Humiliated, “he unceremoniously bundles her up, and, despite shrieks and struggles, carries her off” to his cabin in the Adirondacks. “There, after she has made various efforts to escape, he chains her up “ and “proceeds to teach her a few lessons.” Helen “doesn’t realize how much she loves him” until she renders him unconscious by means of a telephone receiver to the head. (An ad for the 1920 film version of A Misleading Lady, the second of three that were made, touched on the misogyny that was always more or less on display in the caveman meme: “It Wasn’t So Much WHAT She Said, as HOW She Said It — Nor Yet WHAT She Did as HOW She Did It — That Turned Jack Craigen from a Woman Hater to a Cave-Man Lover.”)

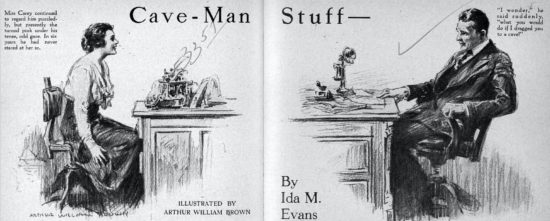

Ida M. Evans’s 1917 Redbook magazine story, “Cave-Man Stuff,” was a slightly more realistic take on forced abduction. After Mildred Gaversby turns down his eighth or ninth marriage proposal, Henry Watson, “a rising young broker, in this land of the free and the shrewd,” whines “but you’ve got to marry me!”

“‘I’ve got to,’ mocked Miss Gaversby. ‘Is that so? Oh, you cave-man!”

Thus, a “cave-man stunt” gets into his head. “He had read a lot of stories and seen several plays wherein a disdained, determined, love-driven gentleman picked up a lady, tucked her, shrieking, under his arm or into a taxi … and carried her to some secluded, remote place, apartment, tenement or prairie, and kept her there, sullen and rebellious — in extreme cases clubbing her in fond but brutal fashion — until she finally consented to be his loving, brainy better half.” However, this has never seemed feasible to Henry, who believed that even “a mild little shriek” would be overheard. “Moreover, he was sure that the average American woman, unless she were fingerless” could make a “quick exit with a hairpin or nail file.” He nevertheless borrows his buddy’s fishing cottage in Wisconsin and plans to kidnap Mildred and her friend, Alice, who he tells about the plot while they are already en route. A sullen Mildred still refuses to marry him, Alice becomes annoyed as the dainty food runs out, and then it starts to rain. The river rises and they are trapped at the cabin for weeks longer than Henry had planned. By the time a farmer comes to rescue them, they all hate each other. At the end of the story, Henry is back in his office and has a crush on his stenographer.

How did real women feel about modern cavemen and their brutish ways? Columnist Nixola Greeley-Smith opined in 1911 that young women were most susceptible to cave-man methods, no matter how rude. Mature women (“from twenty-five to forty”) simply had no use for the “poor old cave man with his claptrap thrills.” They preferred flattery.

“To Find Out How a REAL Cave-Man Makes Love” was the provocative title of a 1922 syndicated article. There was “a romantic fascination and mystery about the word ‘cave-man,’ which has found its way into the drama and the movies and the novel.” Now, the English novelist and explorer, Lady Dorothy Mills, proposed to visit the surviving “remnants of a tribe of Troglodytes” in Northern Africa to research what the cave-man’s “love-making is really like” for an upcoming novel.

She could have saved herself the trip. In 1919, the third installment of “How Men Make Love,” a newspaper series by June Elvidge, a silent film actress and allegedly “The Most Proposed-to Woman in the World,” was devoted to “The Cave Man Lover.” According to Elvidge, this was the “most thrilling” type of man, as long as you liked being “mastered and dominated.” A woman who was “self-reliant,” no doubt like the globetrotting Lady Mills, needed to “beware of the cave man lover. He is not for you.”

PLANET OF PERIL: THE SHIFTERS | THE CONTROL OF CANDY JONES | VINCE TAYLOR | THE SECRET VICE | LADY HOOCH HUNTER | LINCOLN ASSASSINATION BUFFS | I’M YOUR VENUS | THE DARK MARE | SPALINGRAD | UNESCORTED WOMEN | OFFICE PARTY | I CAN TEACH YOU TO DANCE | WEARING THE PANTS | LIBERATION CAN BE TOUGH ON A WOMAN | MALT TONICS | OPERATION HIDEAWAY | TELEPHONE BARS | BEAUTY A DUTY | THE FIRST THRIFT SHOP | MEN IN APRONS | VERY PERSONALLY YOURS | FEMININE FOREVER | “MY BOSS IS A RATHER FLIRTY MAN” | IN LIKE FLYNN | ARM HAIR SHAME | THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE FLAPPER | THE GHOST WEEPS | OLD MAID | LADIES WHO’LL LUSH | PAMPERED DOGS OF PARIS | MIDOL vs. MARTYRDOM | GOOD MANNERS ARE FOR SISSIES | I MUST DECREASE MY BUST | WIPE OUT | ON THE SIDELINES | THE JAZZ MANIAC | THE GREAT HAIRCUT CRISIS | DOMESTIC HANDS | SPORTS WATCHING 101 | SPACE SECRETARY | THE CAVE MAN LOVER | THE GUIDE ESCORT SERVICE | WHO’S GUILTY? | PEACHES AND DADDY | STAG SHOPPING.

MORE LYNN PERIL at HILOBROW: PLANET OF PERIL series | #SQUADGOALS: The Daly Sisters | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: BLOW-UP | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA series | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Waiting Man | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Young Romance | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife | HILO HERO ITEMS on: Tura Satana, Paul Simonon, Vivienne Westwood, Lucy Stone, Lydia Lunch, Gloria Steinem, Gene Vincent, among many others.