AFROFUTURISM (10)

By:

July 18, 2019

We are pleased to present a 10-part series exploring the aesthetics and visual rhetoric of Afrofuturism, by HILOBROW friend Adrienne Crew — who previously brought us an exploration of P-Funk’s Afrofuturism.

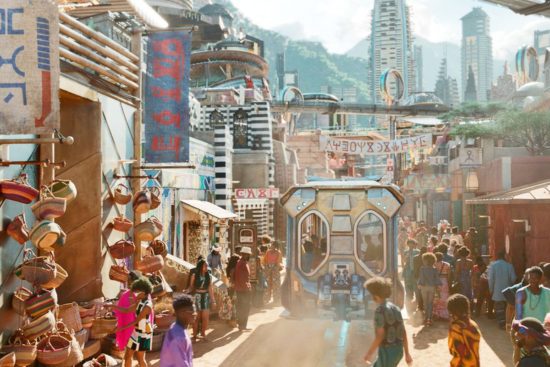

Wakanda 2019 is around the corner! Held in Chicago at the end of July, Wakandacon is a three-day celebration of Afrofuturism in pop culture, gaming and tech. But the biggest attraction is the encouragement of black cosplay inspired by the 2018 blockbuster film Black Panther.

Black Panther resonated with film-goers due to its eye-catching production design and depiction of a utopian African nation, Wakanda. Wakanda revives black viewers’ longing for an alternate African history untainted by the trauma of the slave-trade, colonialism and European imperialism. Wakanda embodies the fantasy of an African nation that has enjoyed the liberty to actualize its full potential.

This idea of a black utopia, protected from European interference, is not new. In fact, most oppressed peoples — Jewish people, Pakistanis, Indians, Celts, Palestinians, Native Americans, Central Europeans, Slavs, Pacific Islanders, Asians — share a similar fantasy narrative where their culture remains intact and unmolested by outsiders.

My favorite recent version of the African American version of this ideal is a Key & Peele sketch called “Negrotown”. A harbinger of Jordan Peele’s prowess in juggling complex tones, “Negrotown” starts with Keegan-Michael Key being harassed by a white cop. Hitting his head while struggling with the cop, Key finds himself transported to a magical, musical land called Negrotown. Peele, acting as a sort of Music Man/Professor Howard Hill cum psychopomp, guides Key into this world with a song that begins with these words:

Follow me to a place I know

It’s a place to

Be if your skin is brown.

I’m talking about Negrotown.

“Negrotown” is not that far-fetched! There’s historical precedent for this fantasy.

The Republic of Liberia, a country on the West African coast, began as a settlement of the American Colonization Society — the members of which believed black people would face better chances for freedom and prosperity in Africa than in the United States. (The ACS was founded by white people, many of whom wanted to get free people of color out of the South; but abolitionists joined, as well. The group met with objections from those African-Americans who wished to remain in the land of their birth, and saw colonization as a racist strategy.) Liberia declared its independence in 1847. In the early 1920s, in response to growing xenophobia, anti-black discrimination, and state-sanctioned segregation in the United States, the Jamaican-born American political activist Marcus Garvey sought to develop Liberia as a homeland in Africa.

Black Panther is just the latest representation of a utopian ambition long held by the African diaspora.

From 1936–1938, the African American author and social critic George Schuyler serialized his novel Black Empire in a black weekly newspaper, The Pittsburgh Courier. A black conservative who loathed Communism and the New Negro movement promoted by members of the Harlem Renaissance, Schuyler’s tale — a satire of Marcus Garvey and his black nationalist devotees — follows the adventures of a radical, racist African American leader who uses high technology like solar power, hydroponics and death ray weapons to found an independent African country and expel white colonists.

The black utopia ideal animated the development of Pan-Africanism, a belief that all Africans and people of African descent shared a common destiny as well as an interconnected history. In the 18th and 19th centuries, religious institutions like Philadelphia’s Free African Society and its progeny — the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, the Bethel African Methodist Episcopalian Church — developed Pan-African concepts. The Bethel AME was an important way station in the Underground Railroad.

Building on the activities of African diasporic activists who convened the first Pan-African conference in Chicago in 1893, and the Pan-African Association (PASS) in London, Pan-Africanism exploded in the 1960s and ’70s. Delegates from the United states, African nations, Europe, India, the Middle East and the Caribbean met frequently to discuss strategies for fighting discrimination and liberating African nations from European colonial rule. In the 1970s and ’80s exiled black American radicals, like Pete O’Neal, found refuge in African nations.

W.E.B. Du Bois convened the fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester in 1945. After the end of World War II, Pan-Africanism reached critical mass. Du Bois and Trinidadian journalist George Padmore emigrated to Ghana; and prominent African nationalist leaders like Kwame Nkrumah, Sékou Ahmed Touré, Ahmed Ben Bella, Julius Nyerere, Jomo Kenyatta, Amilcar Cabral, and Patrice Lumumba gathered to form the Organization of African Unity in 1963. Ryszard Kapuściński’s 1998 book Shadow of the Sun does a good job documenting the Pan-African movement; particularly his memories of hanging out at the New Africa Hotel in Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), where African nationalists like Nelson Mandela resided with other nationalist exiles. The spot attracted intellectuals and celebrities eager to build a Pan-African movement.

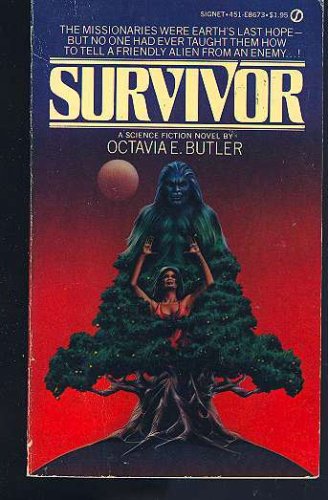

Octavia E. Butler explored the tricky legacy of colonization in her 1978 novel Survivor, which focuses on Alanna Verrick, adopted daughter of white missionaries, who travels to another planet to form an earth colony on a planet already inhabited by a local species. Alanna confronts and reframes history of imperialism by helping the warring indigenous citizens find a sustainable peace. In later years, Butler would disavow this novel and withdraw it from publication: In interviews, she said that she felt it still held a “colonialist gaze,” and dismissed it as her “Star Trek novel.” The similarly themed space colonist movie Avatar (2009) demonstrates that Butler had the right idea to disavow Survivor.

In 2009, William Hayashi took the black utopia concept to the moon. His Dark Side trilogy starts with the novel Discovery, in which a black astrophysicist discovers how to control gravity in the mid-1960s and recruits like-minded African Americans to build a spacecraft to take them to the moon — where they establish a hidden underground colony years before NASA’s arrival. Hayashi published two more novels in a planned seven-part series: Conception (2013) and Confrontation (2015).

While Hayashi’s work is self-published, it’s comforting to know that African Americans are telling the stories that re-frame mainstream science fiction tales about space exploration and colonization and recount the costs involved in such endeavors. Indeed, pulp fiction’s origins were always based on adventure tales of conquest at the expense of indigenous peoples: whether the Dark Continent, as Africa’s impenetrable interior was called, or the American West.

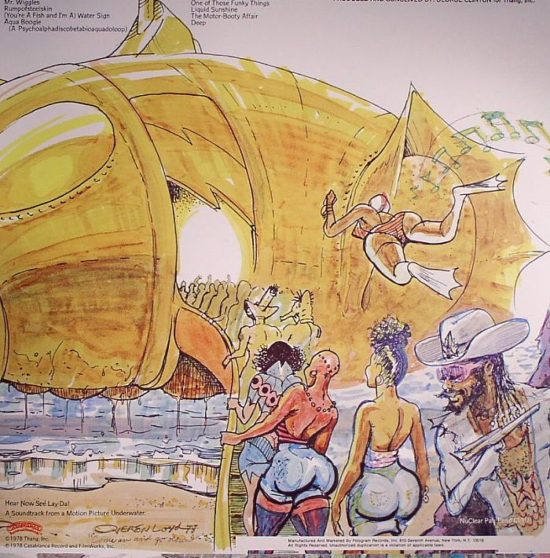

Given the disastrous outcomes of exploration and colonialization, it’s not surprising that indigenous cultures hide from newcomers. Musicians have been especially adept at articulating the impulse to evade conquers. Parliament explored the idea in depth in their 1978 concept album, Motor Boogie Affair. The album explores the idea of a black Atlantis — populated by sexy, funky residents evading Sir Nose D’VoidofFunk. These Afro Aquamen equate swimming with dancing.

The master of ceremonies, for Motor Boogie Affair, is Mr. Wiggles — who introduces this world in the song “Aquaboogie”:

Comin’ to you from #1 Bimini Road, (I got a string on my thang)

In beautiful downtown Atlantis (Rhythm in my thang)

Where you might see the jellyfish jammin’ with the salmon (I can do my thing underwater)

Come face to face with a mouth named Jaws (I got a string attached to my thang)

Freak out with a Mermaid named Rita (When you pull my string)

And meet Mr. Wiggles the Worm (I can do my thang like I oughta)

George Clinton envisioned Motor Boogie Affair as a transmedia product: Designed by Overton Loyd, the album came with paper doll cutouts and a pop-up gatefold. A short TV commercial starring Bootsy Collins accompanied the album’s release.

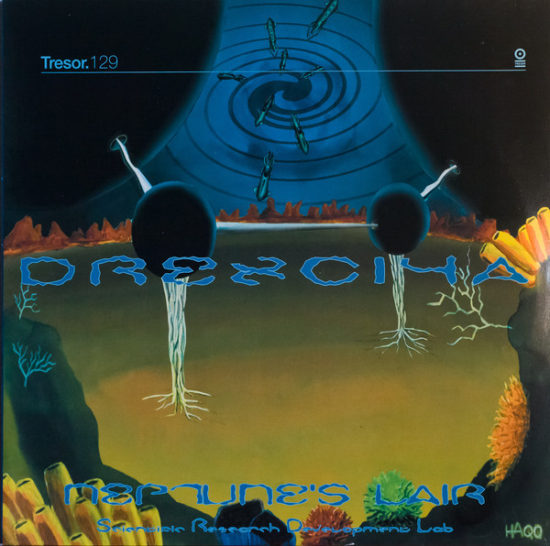

Clinton’s genius inspired other musicians to explore the black Atlantis concept at a deeper level. In the late ’90s Detroit, the techno duo Drexciya released several albums that explored the mythology of an underwater country populated by the unborn children of pregnant African women thrown from slave ships. The children evolved to become water-breathing humanoids.

In 2017, Clipping, an experimental hip hop group — composed of rapper/actor Daveed Diggs and producers William Hutson and Jonathan Snipes — took the idea further in their song “The Deep,” produced as part of a This American Life episode entitled “We Are In The Future.” Like Drexciya’s work, the song also explores an underwater society built by water-breathing descendants of African slave women tossed overboard slave ships during the Middle Passage. The song was nominated for a Hugo Award in 2018; in 2019, Simon & Schuster published a fictionalized adaptation authored by Rivers Solomon.

The trope of hidden Afrocentric worlds give me hope. I’d like to see more media explore science fiction from a culturally sensitive perspective. As global warming kills our planet, space exploration is an inevitable alternative. I hope Black Panther and its imitators awaken a new paradigm, encouraging people to reconsider the harmful effects of capitalist-based exploration and colonization. Like Zion’s revolution in The Matrix franchise, a new world awaits us.

AFROFUTURISM: INTRODUCTION | HAIR POLITICS | BODY HORROR | TIME TRAVEL | SWEET CHARIOTS | ALIEN NATION | A WAY OUT OF NO WAY | ROBOT LIBERATION | ADAPTATION & HYBRIDISM | STARSEEDS | BLACK UTOPIA. ALSO SEE: P-FUNK AFROFUTURISM | SAMUEL R. DELANY | OCTAVIA E. BUTLER | W.E.B. DUBOIS’S “THE COMET”.