10 Best Adventures of 1939

By:

July 15, 2019

Eighty years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Nineteen-Thirties (1934–1943) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from 1939 that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

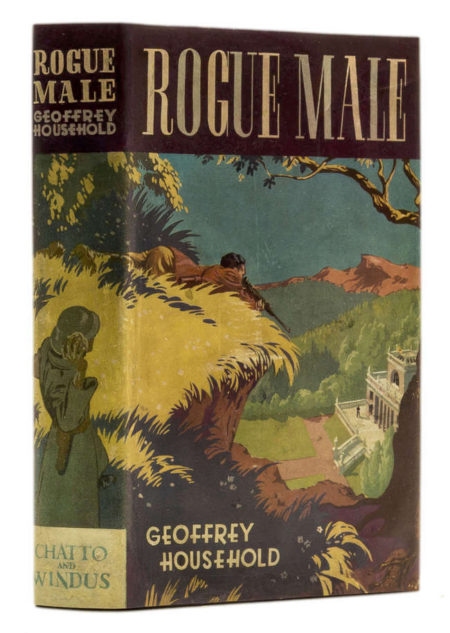

- Geoffrey Household’s hunted-man adventure Rogue Male. One of my favorite thrillers — and, along with The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915) and “The Most Dangerous Game” (1924), one of the top-three most excellent hunted-man stories of all time. Our protagonist, an unnamed British professional hunter, is passing through a Central European country that is in the thrall of a vicious dictator; on a whim, he uses his stalking skills to penetrate undetected into the dictator’s private compound — then gets his target lined up. Before he can decide whether or not to pull the trigger, he’s captured. Tortured by the dictator’s secret service, then left for dead, the hunter flees through enemy territory back to England. This ordeal is already an amazing one, well worth the price of admission. But our protagonist isn’t safe, in London; agents of the dictator are after him. After a harrowing pursuit through the London Underground, he sneaks off to rural Dorset and goes underground — literally. This time, he’s the one being stalked — by a relentless, sadistic hunter, Major Quive-Smith (George Saunders, in the 1941 film version: perfect casting), who is in the pay of the enemy. When Quive-Smith tracks our man to his “holloway,” who will survive? Fun facts: In Fritz Lang’s fine 1941 movie adaptation, Man Hunt, starring Walter Pidgeon and Joan Bennett, the dictator is explicitly identified as Hitler. There was also a 1976 BBC TV adaptation starring Peter O’Toole as the British hunter. David Morrell, author of the 1972 hunted-man thriller First Blood, has acknowledged being deeply influenced by Rogue Male. Also see Robert Macfarlane’s Holloway, originally published in 2012 by the amusingly titled Quive-Smith Press.

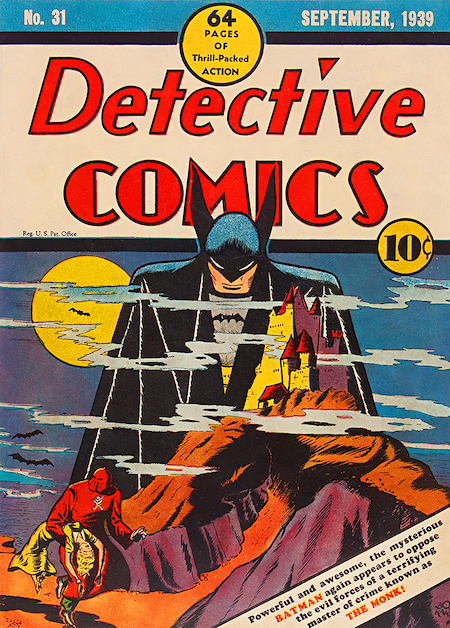

- Bob Kane and Bill Finger’s Batman comics (serialized in Detective Comics and other titles, 1939–present). In 1939, Detective Comics Inc., the company that had introduced Superman the year before, was looking for another hit. Drawing on inspirations from Sherlock Holmes and Dick Tracy (brilliant detectives) to the Scarlet Pimpernel, Zorro, and the Gray Seal (seemingly idle, foppish rich men who donned masks when meting out vigilante justice on behalf of the downtrodden) to the Lone Ranger (murdered family), the Phantom (whose costume lent him an aura of fearsome mystery), and the Shadow (a dark knight motivated by revenge), 22-year-old artist Bob Kane and his 21-year-old ghostwriter, Bill Finger, conjured up Bruce Wayne and his costumed alter ego, the Batman, “weird menace to all crime.” The character first appeared in Detective Comics #27; the plots of his crudely drawn first stories are drawn from pulps and Poe: Batman knocks a murderous businessman into a vat of acid; Batman torches the laboratory of a mad scientist, Doctor Death; a cowled monk with hypnotic powers (who turns out to be a werewolf-vampire) hypnotizes Wayne’s girlfriend and lures her to his Hungarian castle… where he’s shot by Batman, whose gun is loaded with silver bullets! Batman’s origin story appears in issue 33, as prelude to a particularly lurid sci-fi yarn about a death ray-firing Dirigible of Doom. Robin, one of comics’ first teen sidekicks, made his debut in 1940 — a wise-cracking, joyous Watson to Batman’s Holmes. Sales doubled. Batman received a solo title, stopped carrying a gun… and one of the most popular comic-book characters of all time was launched. Fun facts: Amateur comic-book exegetes have done a masterful job of elucidating Kane and Finger’s inspirations/plagiarisms: the Shadow story “Partners Of Peril”; “The Grim Joker,” a story by the same author; panels from Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon strip; panels from Henry E. Vallely’s 1938 Big Little book Gang Busters In Action; the silent movie The Man Who Laughs; and more. PS: The Batmobile, introduced in 1949, redefined and modernized Batman; and the yellow circle around the bat logo on his costume was introduced in 1964.

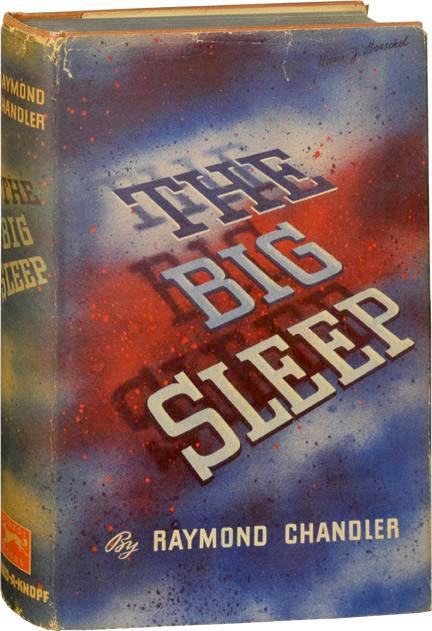

- Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe crime adventure The Big Sleep. In Los Angeles private eye Philip Marlowe’s first outing, he is hired by the elderly General Sternwood to stymie an attempt by a bookseller, Arthur Geiger, to blackmail Sternwood’s out-of-control younger daughter, Carmen. Marlowe discovers that Geiger is actually in the pornography business; he stakes out Geiger’s home, only to discover Geiger dead and Carmen drugged and naked, in front of an empty camera. The next day, he finds out that the Sternwoods’ car was found driven off a pier, with their chauffeur dead inside. The police want to know if Marlowe was hired to find Regan, the missing husband of Carmen’s big sister, Vivian; Vivian wants to know, too. It’s a complex story, with plenty of double-crossing and secrets that aren’t revealed into late in the game; and there’s some gritty action. But what’s so extraordinary about The Big Sleep — what makes it one of the best novels (in any genre) of the 20th century — is Chandler’s hardboiled, yet witty prose. Critics often disparage Chandler, when they compare his work with that of the tougher Dashiell Hammett; Chandler himself was a Hammett fan, calling his predecessor “the ace performer.” But Chandler’s wit is killer: “She lowered her lashes until they almost cuddled her cheeks and slowly raised them again, like a theatre curtain. I was to get to know that trick. That was supposed to make me roll over on my back with all four paws in the air.” And his puzzle-like plots are beautifully constructed. Here, even when all the loose ends of the plot have been wrapped up, Marlowe is nagged by Regan’s disappearance — when he investigates, that’s when his troubles really begin. Fun facts: Howard Hawks’s 1946 adaptation of The Big Sleep, starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, is terrific; William Faulkner, Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett, enhancing Chandler’s own writing, turned out one of the most wickedly clever screenplays ever. There is also a 1978 British adaptation, starring Robert Mitchum.

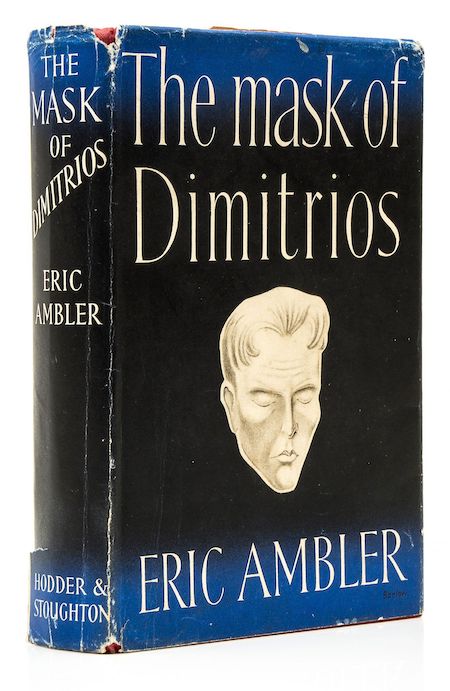

- Eric Ambler’s espionage/crime adventure The Mask of Dimitrios (US title: A Coffin for Dimitrios). Ambler’s fifth thriller is the one for which he is best known. Charles Latimer, a writer of genteel murder mysteries on holiday in Turkey, is introduced to a Colonel Haki, who claims to admire his stories — and who turns out to be head of the Turkish secret police. Haki has just discovered the body of a drowned man whose identity papers reveal that he is Dimitrios Makropoulos, a large-scale drug dealer, pimp, and murderer; he challenges Latimer to find anything romantic about the life of this villain. Our protagonist embarks on journey across Europe, in an attempt to fill in the missing gaps of Dimitrios’s official police record; he has become fascinated with this character, not as an indivdual but as a symbol of the increasingly ruthless times. Each person that Latimer meets — from a left-wing journalist to a master spy — has an idiosycratic story to relate. But Latimer pokes his nose into the wrong places, and soon he’s involved in desperate matters — not a struggle of good vs. evil, but a struggle among amoral entrepreneurs to profit from ethnic cleansing, ideological conflict, and political assassination. Some readers may find the novel too expository, not sufficiently action-packed; but its slow unfolding of secrets and atmospherics, and realistic depiction of exotic locales, makes it a classic of its genre. Fun facts: The Dimitrios character was inspired by the early career of munitions kingpin Sir Basil Zaharoff; and the story’s fictional assassination attempt was loosely based on a 1923 attempted assassination of Bulgaria’s prime minister. Jean Negulesco directed a 1944 adaptation of the novel, starring Sydney Greenstreet, Zachary Scott, Faye Emerson, and Peter Lorre.

- Flann O’Brien’s ’pataphysical picaresque The Third Policeman (w. 1939–1940, p. 1967). Our story’s unnamed narrator confesses to murder, right off the bat — so if this is a crime adventure, it’s one without any mystery; and yet it’s the most mysterious thing you’ll ever read. The narrator finds himself in a sort of alternate dimension; although it may resemble the area surrounding his rural Irish home, its operating system appears to run on a different set of metaphysical laws. Writing for The Irish Times as Myles na gCopaleen, the author generated endless satirical theories, hypotheses, and fantastical inventions; The Third Policeman puts these sorts of ideas into action — which is why I describe it as ’pataphysical. The narrator encounters a machine that will make a block of gold; a cigarette that never gets used up; and an army of one-legged men, who tie themselves together in pairs when entering battle. Perhaps most alarmingly, he discovers bicycles that are half-people, and vice versa — as well as fat local policeman who closely monitor the movements of local citizens, out of concern for this bicycle-transmogrification situation. The ancient Greeks assigned fictional but thematically appropriate deaths to their bygone poets, and one begins to get the sense that something of the sort may be going on here — for our narrator, it seems, is an aficionado of the crackpot theories of a philosopher named De Selby, whose (fictional) books The Country Album, A Memoir of Garcia, and Layman’s Atlas, among others, theorize that the phenomenon of night is actually an accumulation of “black air” caused by pollution, etc., etc. Most improbably of all, by the end of the novel O’Brien will have tied all of this stuff together beautifully. Fun facts: After The Third Policeman failed to find a publisher, the author — whose real name is Brian O’Nolan — withdrew the manuscript from circulation and claimed it had blown out of a car window. In fact, it sat on the sideboard in his dining room until his death in 1966.

- Arthur Ransome’s Swallows & Amazons adventure Secret Water. The eighth Swallows & Amazons book follows We Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea (1937), in which the Walker children inadvertently but heroically navigate the North Sea at night, in a small sailing cutter. As a reward, their parents take them camping on an island in Hamford Water — a tidal inlet between Walton-on-the-Naze and Harwich in Essex — where, once their father is called away on naval business, they are “marooned” with instructions to survey and chart the area. Part of the nerdy pleasure of this installment in the series is learning how to make a proper map — and watching illustrations of the Walkers’ map of the inlets, coves, mudflats, and estuaries of “Walker Island,” and the “Secret Water” area, evolve. Bridget, formerly known as baby “Vicky,” is now four years old; she’s a great addition to the expedition. Titty and Bridget find mysterious footprints, which they track to the lair of a local boy, whom they nickname “Mastodon”; and there’s another family of unsupervised children camping in the area, the “Eels,” who are initially hostile. Just in time, the Amazons show up — hooray! A corroboree — modeled after theatrical events at which Australian Aboriginals interact with the Dreamtime, is planned… but when Bridget is trapped in the middle of a ford by a rising tide, disaster looms. Will she make it? Fun facts: Ransome used to sail to Hamford Water in his yacht Nancy Blackett (named after the elder of the Amazon sisters). He moved the action of the series away from England’s Lake District in order to offer his characters room to explore.

- Graham Greene’s espionage adventure The Confidential Agent. D, a leftist literary scholar from an unnamed European country in the midst of a civil war (one thinks immediately of Spain), is en route to England when he spots L, an aristocratic supporter of the fascist rebels who killed his wife. Both men are in the country to secretly buy coal from the mine-owning Lord Benditch; meanwhile, Benditch’s daughter, Rose, falls in love with D — though she’s engaged to Benditch’s right-hand man, Forbes (a sympathetic Jewish character). An unlikely secret agent, the intellectual D is beaten and robbed by L’s thuggish chauffeur, then nearly killed when he meets in London with his contact, K. D’s authenticating documents are stolen, so Benditch won’t talk to him… and the official at his country’s embassy is a supporter of the fascists. Worse, he’s framed for murder. At last, the traumatized D has had enough of the insults, beatings, and chicanery. He grabs a gun, there’s a chase, an innocent character is killed, and a double agent is exposed. D has botched his mission, it seems — but at the very least, can he prevent the fascists from buying Benditch’s coal? And might he and Rose escape from England together? Fun facts: Greene wrote this “entertainment” in six weeks, with the help of Benzedrine. The Chanson de Roland is mentioned; the author was testing the limits of the thriller — how chivalrous can a modern character possibly be? The novel was adapted in 1945, by Herman Shumlin, as Confidential Agent; the movie stars Charles Boyer, Lauren Bacall (whose performance was panned), Katina Paxinou, and Peter Lorre.

- E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Lensman sf adventure Grey Lensman (serialized, 1939; in book form, 1951). Picking up where Galactic Patrol (serialized 1937) left off, shortly after Unattached (“Gray”) Lensman Kimball Kinnison’s attack on a secret base of the Boskonian space-criminals/conquerors who’ve been threatening Civilization, Grey Lensman introduces new characters, new planets, and a new villainous race: Lovecraftian horrors known as the Eich. The frame of Smith’s already ambitious tale expands dramatically, here; it’s a startling way to kick off what could have been a straightforward sequel. This novel has everything we’ve come to expect of Smith: space battles, melodramatic adventure, and chivalric romance — with Clarissa MacDougall, who in Second Stage Lensmen will become Civilization’s first female Lensman. (A Lensman is a genetically enhanced bearer of the “Lens,” an alien technology that bestows telepathic and other powers on a worthy user; it’s incontrovertible that DC Comics’ Green Lantern Corps was a Lensman ripoff.) Mounting an expedition aboard the super-dreadnought Dauntless into the so-called Second Galaxy, Kinnison brings an entire planet home. He then goes undercover and infiltrates Boskonian drug trafficking until he learns the location of the trafficker’s galactic jefe, and then the location of the Eich; also, he works with the galaxy’s greatest scientists to develop a “Negasphere.” Kinnison and his reptilian comrade Worsel will use this planet-busting weapon — but not before our hero is blinded, tortured almost to death, and loses his limbs! Thrilling stuff, but also elegantly written. Fun facts: Originally, the series consisted of the four novels Galactic Patrol, Gray Lensman, Second Stage Lensmen, and Children of the Lens, serialized between 1937 and 1948 in the pulp magazine Astounding Stories. Triplanetary (serialized 1934) was reworked to serve as as the first of two prequels to the series; and First Lensman (1950) was written to act as a link between Triplanetary and Galactic Patrol.

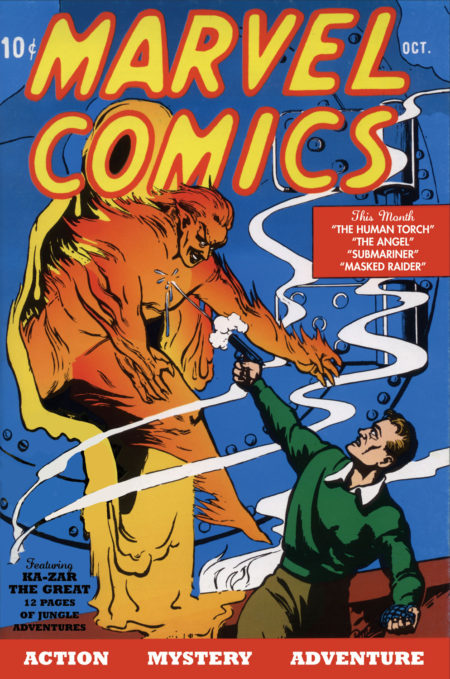

- Marvel Comics (1939–ongoing). Marvel Comics started in 1939, though not exactly as such. The popularity of Superman (who debuted in Action Comics, in 1938), Batman (Detective Comics, 1939), and other superheroes led Martin Goodman, a New York-based publisher of pulp magazines such as All Star Adventure Fiction, Complete Western Book, and Mystery Tales, to start a comics division within his company, Timely Publications. Timely Comics’ Marvel Comics #1 (Oct. 1939) featured the first appearance of Carl Burgos’s android superhero, the Human Torch, and the first generally available appearance of Bill Everett’s undersea antihero Namor the Sub-Mariner. This content was provided by comic-book “packager”; but after Marvel Comics #1 sold nearly a million copies (in two editions), Goodman hired comics writer-artist Joe Simon as Timely’s first editor. Simon brought along his friend Jack Kirby, a talented young artist with whom he’d worked on Blue Bolt; the Human Torch and Sub-Mariner were soon joined by Simon and Kirby’s Captain America. A 16-year-old Stan Lee, a cousin of Goodman’s by marriage, also joined Timely in 1939; he was promoted to interim editor a few years later, after Simon and Kirby left for the fledgling DC Comics. In the early ’60s, Lee and Kirby’s Fantastic Four and other titles would revolutionize the medium; by then, Timely had been renamed: Marvel Comics. Fun facts: The year 1939 also saw the launch of MLJ Comics (which would become Archie Comics), Fawcett Comics (Captain Marvel), Fox Feature Syndicate (Blue Beetle), Lev Gleason Publications (Crime Does Not Pay), Standard/Better/Nedor (The Black Terror), and Quality Comics (Plastic Man).

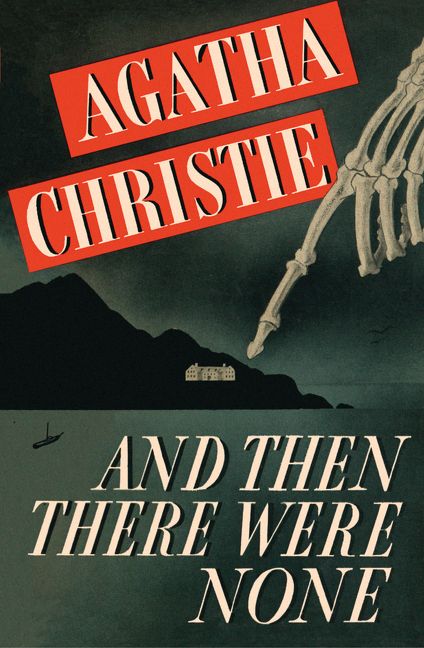

- Agatha Christie’s crime adventure And Then There Were None. Eight people are invited to spend time — as an employee, in some cases; as a holidaying guest, in others — at a small, isolated island off the Devon coast of England. They are met by a butler and cook-housekeeper, who inform them that their host, U.N. Owen (unknown, they’ll soon figure out), whom none of them has ever met, will arrive later. A framed copy of a nursery rhyme, “Ten Little Niggers” (“Ten Little Indians,” in later editions), hangs in each guest’s bedroom; the sinister import of this décor will soon become apparent. A pre-recorded message accuses each of the island’s 10 inhabitants of having gotten away with murder; one of them dies that first evening, of cyanide poisoning. There’s no way off the island, and the violent deaths keep coming. This is a murder mystery without a detective: the ever-shrinking group seeks to determine which of their number is the killer. Will they figure out what’s happening, before nobody is left standing? In a postscript, a fishing ship picks up a bottle inside its trawling nets; the bottle contains a written confession of the killings, which explains everything. Fun facts: This is not only Christie’s most popular novel, but the world’s best-selling mystery; it’s been called one of the essential crime reads written by women in the last 100 years. First published in the UK as Ten Little Niggers, after the racist nursery rhyme which serves as a major plot point; beginning in 1964, it was published as Ten Little Indians. There have been several film and TV adaptations; the 1976 movie Murder by Death is a clever parody. Most importantly, in 2011 I wrote a “Golden Fleece”/And Then There Were None mashup, for HILOBROW.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.