Best YA & YYA Lit 1972

By:

July 12, 2019

The following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Sixties (1964–1973) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite YA and YYA adventures published in 1972. Enjoy!

- Richard Adams’s talking-animal survival adventure Watership Down. An Aeneid-like epic in which a ragtag band of rabbits escape the destruction of their warren and journey across south-central England in search of a new home. Their unlikely leader is Hazel, whose main concern was to protect his oddball (visionary) brother Fiver; the charismatic star of the story is the gruff, tough rabbit Bigwig. These unlikely misfits encounter predators, snares, and automobiles; and they must elude the Owsla — the security force of their own warren, sent to fetch them back. Though the ever-growing group is tempted to join a couple of un-free rabbit societies, Hazel, Fiver, and Bigwig are fiercely determined to start their own warren… which they finally do, at Watership Down, a hill in the north of Hampshire. However, they need does — which leads them into more perilous adventures. And in the end, they must survive an attack led by Woundwort, the monstrous leader of a rival warren. Throughout, we hear inspirational excerpts from the lapine mythology of El-ahrairah the trickster. James Parker has described the book as “an unprecedented mash-up of eco-anxiety, homely bottom-of-the-garden anthropomorphism, real violence, and febrile mythmaking.” Fun facts: Watership Down was Richard Adams’s debut novel; it won the Carnegie Medal and Guardian Prize. It was adapted as a 1978 animated film; a 2018 miniseries adaptation, featuring the voices of Nicholas Hoult, James McAvoy, John Boyega, and Rosamund Pike as the Black Rabbit of Inlé. In 1996, Adams published a collection, Tales from Watership Down, featuring “Notes on Pronunciation” and a “Lapine Glossary.”

- Peter Dickinson’s YA historical adventure The Dancing Bear. When barbarous Huns attack Byzantium, they carry off Ariadne, a wealthy young woman. Sylvester, a young slave in Ariadne’s household who’d survived the raid by hiding out with Bubba, a dancing she-bear, bravely journeys into Hun territory on a quixotic rescue mission. (He is also fleeing powerful Byzantine traitors who know that he witnessed their treachery, and wnt to silence him.) Our hero is accompanied by Holy John — a dirty, epileptic, narcissistic household saint, who wants to convert the Huns — and by Bubba. Holy John’s interpretations of God’s wishes often save the day; and, when at a point when all seems hopeless, he is able to persuade the Hun’s leader that Bubba is an incarnation of the Holy Spirit. Bubba, by the way, is a wonderful, loving, loyal character — perhaps the best bear in literature. There is a meta-textual aspect to the story; readers young and old will appreciate Dickinson’s self-deprecating humor regarding the effort of conjuring up a historical era in all its social, cultural, political complexity. Fun fact: Dickinson would recall, of this book, that he started telling his sons this story because, when he was at Eton, a teacher had enthralled him with stories about “riots in Byzantium between two religious factions which resulted in a bear-keeper changing sides, so that his daughter, the future Empress Theodosia, became a prostitute in an Aryan brothel and not an Orthodox one.” Dickinson invented the Hun raid on Byzantium to make his sons happy, only to discover that there had been such a raid at exactly the time he’d dreamed one up.

- Rosemary Sutcliff’s historical adventure(s) Heather, Oak, and Olive: Three Stories. Sutcliff’s historical novels often take as their theme the conflicting claims of different cultures on individuals who belong entirely to neither one nor the other. This is the case with the three stories collected here; making a sacrifice in the name of friendship is another important theme. In “The Chief’s Daughter” (originally published in 1966), Nessa, strong-willed daughter of the chief of a clan in pre-Roman Wales, interferes when her people attempt to sacrifice the young captured son of Irish raiders to the Black Mother. In “A Circlet of Oak Leaves” (1965), set in Roman Britain, the retired soldier Aracos never joins his fellow cavalrymen in recounting the events of the defining military adventure of his life — because he did a favor for a friend that he can never reveal. And in “A Crown of Wild Olive” (1971), which is set during a truce in the Peloponnesian War (between Athens and Sparta, the leading city-states in ancient Greece), Amyntas and Leon, rival athletes in the Olympic games, become close friends — despite having been born on opposite sides of the conflict. Fun facts: Illustrated by Victor Ambrus. Due to a chronic illness, as a teenager Sutcliff spent most of her time with her mother — from whom she learned the Celtic and Saxon legends that first inspired her interest in historical stories.

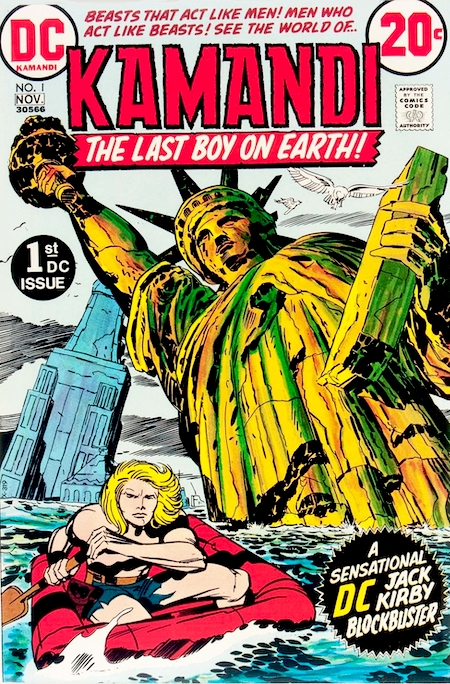

- Jack Kirby’s sci-fi comic series Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth (1972–1976 or so). Kamandi is the last survivor of “Command D” (get it?), an underground shelter where a group of New Yorkers took refuge, at some point in the not-too-distant past, from a radiation-related disaster that made living on the surface untenable. He is an almost feral yet educated teenager, having known nothing of the outside world but what he’s seen on video screens — think of him as a precursor to today’s so-called Generation Z. Emerging at last, like one of the blinkered characters from Plato’s allegory of the cave, into a post-apocalyptic America, Kamandi discovers that the few humans who have survived have in most cases degenerated to a Stone Age level of existence. Many animal species, meanwhile — I won’t go into the back story, it’s a mashup of Planet of the Apes and Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH — have become bipedal, humanoid, and sentient, and possess the power of speech. Equipped with weapons and technology salvaged from the ruins of human civilization, these lions, tigers, and bears have divided up the North American continent into warring kingdoms. Kamandi crosses this landscape, using his wits to survive a series of adventures; he befriends Dr. Canus, the canine scientist of Great Caesar (leader of the Tiger Empire), Caesar’s teenage son Tuftan, the mutated human Ben Boxer, not to mention various savage humans and even an alien. One of the great yarns from Kirby, then working at the peak of his powers; and the map of North America at the end of issue #1 is endlessly evocative. Fun facts: Having failed to acquire the license to publish Planet of the Apes comics, DC editor Carmine Infantino asked Jack Kirby to develop a similar concept. Kirby combined the idea with a comic strip he’d dreamed up in 1956, Kamandi of the Caves. He stopped writing the comic in 1976, after 37 issues, though he drew a few more issues after that.

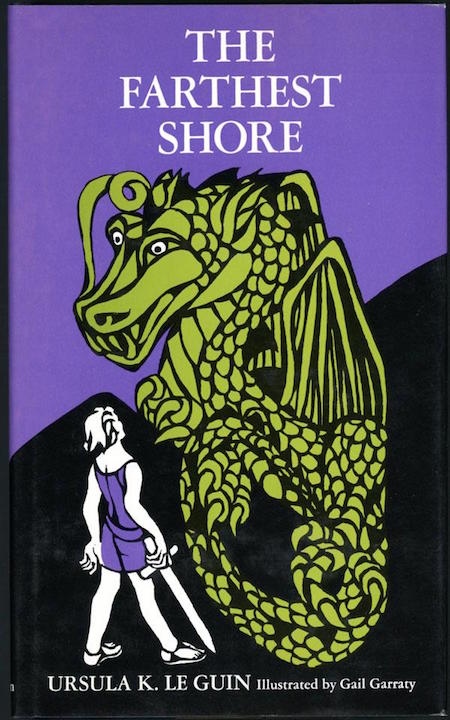

- Ursula K. Le Guin‘s Earthsea fantasy adventure The Farthest Shore. In the final installment of the original Earthsea trilogy, the planet faces an existential crisis: the magic is leaking out of it, into a kind of black hole — and along with the magic is going all courage and conviction, not to mention songs, craftsmanship, and joy! The archmage Ged, whose life and career as a wizard we’ve being following in this series, is now on the elderly side; he and Arren, his young princely sidekick, head out in the Lookfar to investigate. (Arren is not a skilled warrior or gifted wizard; but he is courageous, and one day he’ll be a powerful ruler — so Ged, the Aristotle to his Alexander — wants to impart his own hard-earned wisdom.) They discover that a powerful dark mage, who has made his home among the dragons on Earthsea’s westernmost island, is promising life after death… even if that means destroying the world. A slow-moving adventure, with philosophical musings — not as thrilling as the first two installments. But Le Guin is a wonderful philosopher, so the book is a beautifully written page-turner. Fun fact: Winner of the 1973 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. Originally the series was a trilogy; Le Guin then added Tehanu (1990), The Other Wind (2001), and the story collection Tales from Earthsea (2001). Rather confusingly, the 2006 animated film Tales from Earthsea, directed by Hayao Miyazaki’s son Gorō, was based primarily on The Farthest Shore.

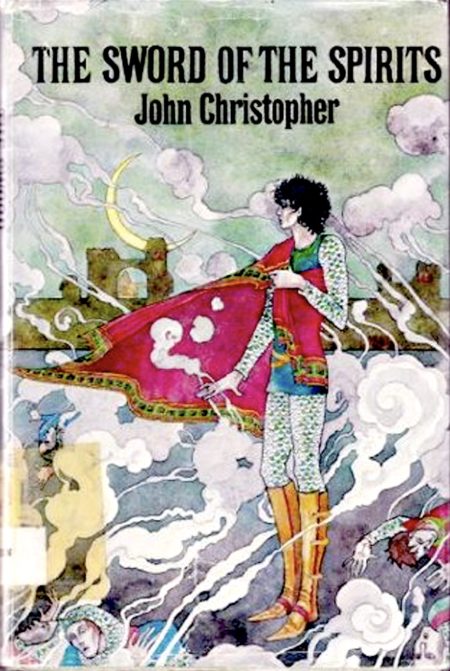

- John Christopher’s YA science fiction adventure The Sword of the Spirits. Before Mike W. Barr and Brian Bolland’s 1982–1985 comic book series Camelot 3000, there was this, the third installment in John Christopher’s Sword of the Spirits trilogy. It takes place shortly after the events of The Prince in Waiting (1970), in which a headstrong young Luke Perry becomes heir to the throne of Winchester, a walled city in the medieval world of post-apocalyptic England, only to flee to the mysterious Sanctuary of the High Seers (a high-tech hideout near Stonehenge) when his half-brother betrays him; and Beyond the Burning Lands (1971), in which Luke becomes a hero in Klan Gothlen (Llangollen, Wales, legendary home of Arthur’s Queen Guenevere), then returns to Winchester to find that the Seers have orchestrated his return to power. Assuming the role of military leader, Luke extends his rule to Winchester’s neighbors, and appears to be on his way to fulfilling the Seers’ mission of unifying England’s independent city-states, in the name of progress. Happily ever after? No! When Luke’s betrothed, Blodwen from Klan Gothlen, falls in love with his friend and principal military advisor, he finds himself on the run again. Summoning a Welsh military forced armed with Seers-provided Sten guns, our brave but difficult-to-like protagonist returns to Winchester to seek revenge… but when the time comes for him to reclaim his throne, will Luke be able to go through with it? Fun facts: I also recommend Christopher’s Tripods trilogy (1967–1968), and stand-alone YA novels of the same period such as The Lotus Caves (1969), The Guardians (1970), Dom and Va (1973), and Wild Jack (1974).

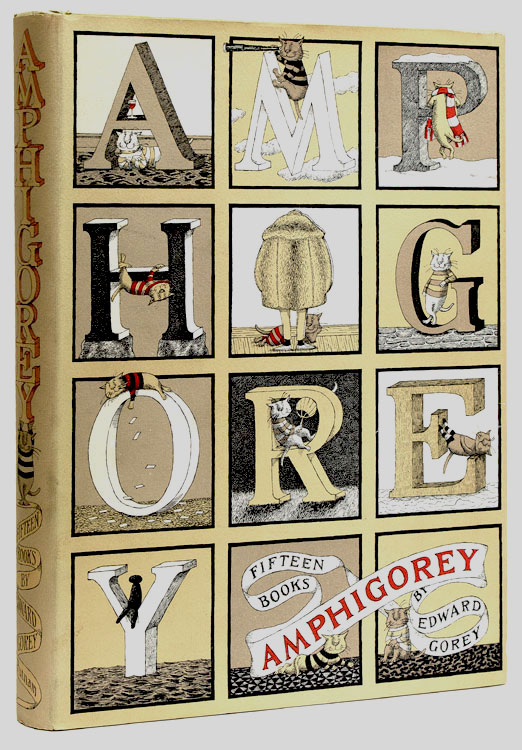

- Edward Gorey’s spooky-kooky illustrated story collection Amphigorey. A spooky-kooky collection of fifteen tales, ostensibly but not entirely intended for children, first published between 1953 and 1965 by one of the most original, self-assured, witty and weird artist-authors ever to sport Converse high-tops and a fur coat to the New York City Ballet. Most of us who grew up in the ’70s can recall, almost word for word, “The Gashlycrumb Tinies” (“E is for Ernest who choked on a peach/F is for Fanny sucked dry by a leech”); “The Wuggly Ump” is a “Jabberwocky”-esque example of kiddie doggerel with an unhappy ending; and “The Bug Book,” a chillingly upbeat fable about six happy and colorful insects who team up to destroy an unpleasant newcomer, was also of particular interest, to me as child. I enjoyed leafing through the rest of the book, too, but it wasn’t until I reached late adolescence that some of its contents — the oft-violent limericks of “The Listing Attic,” the Godot-like meaninglessness of “The Doubtful Guest,” the nearly-naughty “pornographic” story “The Curious Sofa” — started making sense. Other selections here, like “The Unstrung Harp,” a metafictional story about an Edwardian novelist struggling to complete the lurid title narrative, or “The Willowdale Handcar,” “The Object-Lesson,” and “The Sinking Spell,” remain, to this day, capable of teaching me something about the power of leaving things unspoken. Fun facts: The word amphigory, or amphigouri, means “a nonsense verse or composition.” Gorey’s cross-hatched pen and ink drawings decorate not only an edition of H.G. Wells’s War of the Worlds, but the covers of dozens of literary classics, pubished during the paperback revolution of the the mid- to late 1950s when he was working at Doubleday.

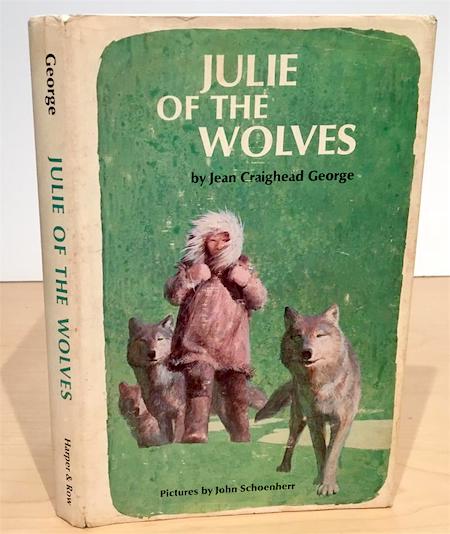

- Jean Craighead George’s frontier children’s adventure Julie of the Wolves. Miyax, a smart, observant 13-year-old Inuk girl, is not only orphaned — when her father doesn’t return from a seal hunt — but coerced into marriage with Daniel, an intellectually disabled young man who assaults her. So she runs off over the tundra, in hopes of eventually reaching San Francisco. Because her father has taught her survival skills, this isn’t as dire a situation as it may seem; however, she won’t last long unless she can find some help. This comes in the form of a wolf pack, with whom — through patient observation and experimentation — she learns to communicate, in a rudimentary way. As the story unfolds, we learn that Miyax once lived with her aunt in an Alaskan town where she attended school, and changed her name to “Julie.” She is adopted by the pack… and when she finds a way to return to her former life, she is torn between the choice of staying with the wolves or going home. Fun facts: Jean Craighead George wrote over 100 books for children and young adults, including My Side of the Mountain (1959). The inspiration for the Newbery Medal-winning Julie of the Wolves derived from a summer she spent studying wolves and tundra at the Arctic Research Laboratory of Barrow, Alaska. Although often taught in school — I remember reading it aloud in the 5th grade — the book is also often challenged because it describes alcoholism, abuse, and sexual assault.

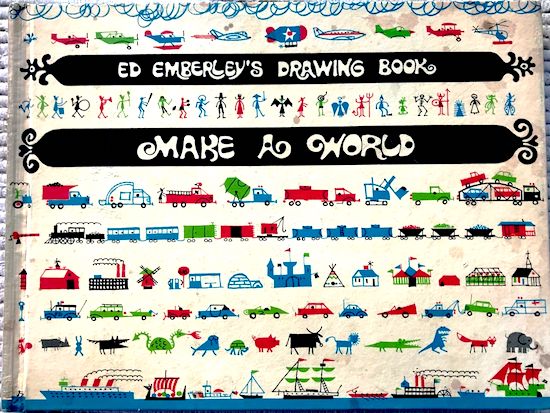

- Ed Emberley’s Ed Emberley’s Drawing Book: Make a World. Massachusetts-based illustrator Ed Emberley had already gained recognition for his simple yet sophisticated — psychedelic, even — work on children’s books like The Wing on a Flea (1961), Yankee Doodle (1965), and Drummer Hoff (1968, written by his wife, Barbara), to mention a few personal favorites, before he turned his hand to encouraging children to draw. I say “encouraging” rather than “teaching,” because Emberley’s drawing books provide practical tools for getting over one’s anxiety about lack of ability, one’s fear of the blank page. (I doubt that anyone, with the exception of Tom Gauld, grew up to draw like Emberley.) Today, many of these guides, from Ed Emberley’s Drawing Book of Faces (1975) to Ed Emberley’s Drawing Book of Weirdos (2004), are still in print; I’ve purchased new editions for my own kids. When I was growing up in the 1970s, however, Make A World, which demonstrates “how to draw enough things to make a world of your own,” was of particular significance, to me — and to my six younger brothers and sisters, too. The author deconstructs over 400 objects, buildings, animals, and characters — from alligators and bulldozers to volcanos and witches — down into their simplest forms. A drawing of a pirate ship is, we discover, composed of variously colored squares and rectangles, triangles and dots, lines and squiggles; and so is everything and everyone else that one could possibly imagine. The book’s final pages are a DIY call to action: make your own comics, posters, books, games! This slim, brilliantly colored book isn’t an adventure novel; I include it on this list because it’s something equally as thrilling: a bottom-up worldbuilding propaedeutic enchiridion. Fun facts: Although it’s impossible to find a cheap used copy of the book, I also highly recommend Emberley’s 1975 illustrated adventure The Wizard of Op, about a “slightly inept wizard” whose spells are depicted as two-page spreads of vibrating, slightly hallucinatory black-and-white optical-illusion patterns.

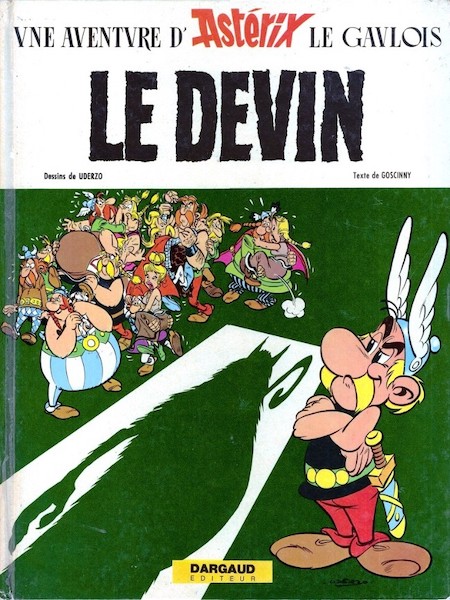

- René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s Le Devin (English title: Asterix and the Soothsayer). Beginning with 1970’s La Zizanie (Strife; English title: Asterix and the Roman Agent), Goscinny’s Asterix stories took on political intrigue, capitalist competition, urban renewal, and other contemporary themes — in each case, showing how these things can threaten the fragile fabric of the Gaul’s quarrelsome but close-knit community. Here, the theme is credulity and superstition — among highbrow Romans and lowbrow Gauls alike. A wolf-cloaked soothsayer, Prolix, visits the village in search of a square meal; his predictions — the weather will clear up; the villagers will brawl — are vague, obvious, and compelling. Even Obelix falls for Prolix’s claim that a beautiful woman will come his way; only Asterix remains skeptical. The Romans weaponize Prolix, whose prophesy of doom causes the villagers to abandon their homes in a panic. Word is sent to Rome: All of Gaul is now conquered! Caesar sends an envoy to confirm the claim, while the Romans prepare to occupy the village. How can Asterix persuade his gullible comrades that Prolix is a charlatan? Alas, the idea that a rumor-mongering conspiracy theorist could sway public opinion, and empower predatory opportunists, is all too timely, right now. Fun facts: Serialized in Pilote (issues 652–673) in 1972. The extended-panel scene on page 10, where several characters observe the disembowelment of a fish, is a reproduction of Rembrandt’s 1632 painting Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp.

BEST SIXTIES YA & YYA: [Best YA & YYA Lit 1963] | Best YA & YYA Lit 1964 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1965 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1966 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1967 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1968 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1969 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1970 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1971 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1972 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1973. ALSO: Best YA Sci-Fi.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.