LEAVE IT TO PSMITH (18)

By:

May 13, 2019

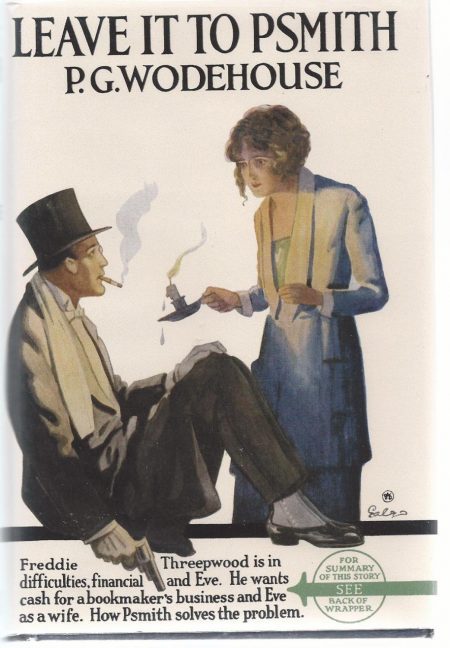

Leave It to Psmith (1923) is the last and most rewarding of four novels featuring the dandy, wit, and would-be adventurer Ronald Eustace Psmith, one of P.G. Wodehouse‘s most popular characters. (“One can date exactly,” Evelyn Waugh claimed, in reference to Psmith’s debut in the 1909 novel Mike, “the first moment when Wodehouse was touched by the sacred flame.”) Leave It to Psmith‘s copyright enters the public domain in 2019; HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize this terrific book here at HILOBROW. Enjoy!

As Lord Emsworth disappeared, it occurred to Psmith that the moment had arrived for him to get his hat and steal softly out of the other’s life forever. Only so could confusion and embarrassing explanations be avoided. And it was Psmith’s guiding rule in life always to avoid explanations. It might, he felt, cause Lord Emsworth a momentary pang when he returned to the smoking-room and found that he was a poet short, but what is that in these modern days when poets are so plentiful that it is almost impossible to fling a brick in any public place without damaging some stern young singer. Psmith’s view of the matter was that, if Lord Emsworth was bent on associating with poets, there was bound to be another one along in a minute. He was on the point, therefore, of rising, when the laziness induced by a good lunch decided him to remain in his comfortable chair for a few minutes longer. He was in one of those moods of rare tranquillity which it is rash to break.

He lit another cigarette, and his thoughts, as they had done after the departure of Mr McTodd, turned dreamily in the direction of the girl he had met at Miss Clarkson’s Employment Bureau. He mused upon her with a gentle melancholy. Sad, he felt, that two obviously kindred spirits like himself and her should meet in the whirl of London life, only to separate again — presumably for ever — simply because the etiquette governing those who are created male and female forbids a man to cement a chance acquaintanceship by ascertaining the lady’s name and address, asking her to lunch, and swearing eternal friendship. He sighed as he gazed thoughtfully out of the lower smoking-room window. As he had indicated in his conversation with Mr Walderwick, those blue eyes and that cheerful, friendly face had made a deep impression on him. Who was she? Where did she live? And was he ever to see her again?

He was. Even as he asked himself the question, two figures came down the steps of the club, and paused. One was Lord Emsworth, without his hat. The other — and Psmith’s usually orderly heart gave a spasmodic bound at the sight of her — was the very girl who was occupying his thoughts. There she stood, as blue-eyed, as fair-haired, as indescribably jolly and charming as ever.

Psmith rose from his chair with a vehemence almost equal to that recently displayed by Mr McTodd. It was his intention to add himself immediately to the group. He raced across the room in a manner that drew censorious glances from the local greybeards, many of whom had half a mind to write to the committee about it.

But when he reached the open air the pavement at the foot of the club steps was empty . The girl was just vanishing around the corner into the Strand, and of Lord Emsworth there was no sign whatever.

By this time, however, Psmith had acquired a useful working knowledge of his lordship’s habits, and he knew where to look. He crossed the street and headed for the florist’s shop.

‘Ah, my dear fellow,’ said his lordship amiably, suspending his conversation with the proprietor on the subject of delphiniums, ‘must you be off? Don’t forget that our train leaves Paddington at five sharp. You take your ticket tor Market Blanding.’

Psmith had come into the shop merely with the intention of asking his lordship if he happened to know Miss Halliday’s address, but these words opened out such a vista of attractive possibilities that he had abandoned this tame programme immediately. He remembered now that among Mr McTodd’s remarks on things in general had been one to the effect that he had received an invitation to visit Blandings Castle — of which invitation he did not propose to avail himself; and he argued that if he had acted as substitute for Mr McTodd at the club, he might well continue the kindly work by officiating for him at Blandings. Looking at the matter altruistically, he would prevent his kind host much disappointment by taking this course, and, looking at it from a more personal viewpoint, only by going to Blandings coukd he renew his acquaintance with this girl. Psmith had never been one of those who hang back diffidently when Adventure calls, and he did not hang back now.

‘At five sharp,’ he said. ‘I will be there.’

‘Capital, my dear fellow,’ said his lordship.

‘Does Miss Halliday travel with us?’

‘Eh! No, she is coming down in a day or two.’

‘I shall look forward to meeting her,’ said Psmith.

He turned to the door, and Lord Emsworth with a farewell beam resumed his conversation with the florist.

The five o’clock train, having given itself a spasmodic jerk, began to move slowly out of Paddington Station. The platform past which it was gliding was crowded with a number of the fauna always to be seen at railway stations at such moments, but in their ranks there was no sign of Mr Ralston McTodd; and Psmith, as he sat opposite Lord Emsworth in a corner seat of a first-class compartment, felt that genial glow of satisfaction which comes to the man who has successfully taken a chance. Until now, he had been half afraid that McTodd, having changed his mind, might suddenly appear with bag and baggage — an event which must necessarily have caused confusion and discomfort. His mind was now tranquil. Concerning the future he declined to worry. It would, no doubt, contain its little difficulties, but he was prepared to meet them in the right spirit; and his only trouble in the world now was the difficulty he was experiencing in avoiding his lordship’s legs, which showed a disposition to pervade the compartment like the tentacles an octopus. Lord Emsworth rather ran to leg, and his practice of reclining when at ease on the base of his spine was causing him to straddle, like Apollyon in Pilgrim’s Progress, ‘right across the way.’ It became manifest that in a journey lasting several hours his society was likely to prove irksome. For the time being, however, he endured it, and listened with polite attention to his host’s remarks on the subject of the Blandings gardens. Lord Emsworth, in a train moving in the direction of home, was behaving like a horse heading for his stable. He snorted eagerly, and spoke at length and with emotion of roses and herbaceous borders.

‘It will be dark, I suppose, by the time we arrive,’ he said regretfully, ‘but the first thing to-morrow, my dear fellow, I must take you round and show you my gardens.’

‘I shall look forward to it keenly,’ said Psmith. ‘They are, I can readily imagine, distinctly oojah-cum-spiff.’

‘I beg your pardon?’ said Lord Emsworth, with a start.

‘Not at all,’ said Psmith graciously.

‘Er — what did you say?’ asked his Lordship after a slight pause.

‘I was saying that, from all reports, you must have a very nifty display of garden produce at your rural seat.’

‘Oh yes. Oh, most,’ said his lordship, looking puzzled. He examined Psmith across the compartment with something of the peering curiosity which he would have bestowed upon a new and unclassified shrub. ‘Most extraordinary!’ he murmured. ‘I trust, my dear fellow, you will not think me personal, but do you know nobody would imagine that you were a poet. You don’t look like a poet, and, dash it, you don’t talk like a poet.’

‘How should a poet talk?’

‘Well…’ Lord Emsworth considered the point. ‘Well, Miss Peavey. … But, of course, you don’t know Miss Peavey. … Miss Peavey is a poetess, and she waylaid me the other morning while I was having a most important conference with McAllister on the subject of bulbs, and asked me if I didn’t think that it was fairies’ teardrops that made the dew. Did you ever hear such dashed nonsense?’

‘Evidently an aggravated case. Is Miss Peavey staying at the Castle?’

‘Is she! You couldn’t shift her with blasting-powder. Really, this craze of my sister Constance for filling the house with these infernal literary people is getting on my nerves. I can’t stand these poets and what not. Never could.’

‘We must always remember, however,’ said Psmith, gravely, ‘that poets are also God’s creatures.’

‘Good heavens!’ exclaimed his lordship, aghast. ‘I had forgotten that you were one. What will you think of me, my dear fellow? But, of course, as I said a moment ago, you are different. I admit that when Constance told me that she had invited you to the house I was not cheered, but, now that I have had the pleasure of meeting you…’

The conversation had worked round to the very point to which Psmith had been wishing to direct it. He was keenly desirous of finding out why Mr. McTodd had been invited to Blandings and — a still more vital matter — of ascertaining whether, on his arrival there as Mr. McTodd’s understudy, he was going to meet people who knew the poet by sight. On this latter point, it seemed to him, hung the question of whether he was about to enjoy a delightful visit to a historic country house in the society of Eve Halliday — or leave the train at the next stop and omit to return to it.

‘It was extremely kind of Lady Constance,’ he hazarded, ‘to invite a perfect stranger to Blandings.’

‘Oh, she’s always doing that sort of thing,’ said his lordship. ‘It didn’t matter to her that she’d never seen you in her life. She had read your books, you know, and liked them; and when she heard that you were coming to England she wrote to you.’

‘I see,’ said Psmith, relieved.

‘Of course, it is all right as it has turned out,’ said Lord Emsworth, handsomely. ‘As I say, you’re different. And how you came to write that… that…’

‘Bilge?’ suggested Psmith.

‘The very word I was about to employ, my dear fellow. … No, no, I don’t mean that … I — I … Capital stuff, no doubt, capital stuff … but …’

‘I understand.’

‘Constance tried to make me read the things, but I couldn’t. I fell asleep over them.’

‘I hope you rested well.’

‘I — er — the fact is, I suppose they were beyond me. I couldn’t see what it was all about.’

‘If you would care to have another pop at them,’ said Psmith, agreeably, ‘I have a complete set in my bag.’

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.