Best YA & YYA Lit 1973

By:

April 22, 2019

The following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Sixties (1964–1973) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite YA and YYA adventures published in 1973. Enjoy!

- Susan Cooper’s YA fantasy adventure The Dark is Rising. On the Venn diagram showing admirers of Susan Cooper’s Dark is Rising sequence and fans of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, I suspect there is little overlap — this, despite the fact that both feature a young English hero who discovers his magical abilities, then undertakes perilous quests in search of artifacts that will assist a rag-tag band of good wizards and witches facing the growing menace of supernatural evil. Cooper’s prose is superior to Rowling’s, but her stories are grimmer. In this installment, we meet Will Stanton, who until the eve of his eleventh birthday believes that he’s an ordinary kid. In fact, he’s an Old One — an immortal being who task it is to serve the Light, and protect the world from the Dark. In later installments, Will will join forces with the Drew siblings (whom we met in 1965’s Over Sea, Under Stone); here, he must travel through time seeking six magical talismans. He is assisted by Merriman, a decidedly un-Dumbledore-like mentor-wizard, and menaced by a sinister Rider and a mad Walker — not to mention a Hunter who represents neither Light nor Dark but wild magic. The mythological sub-strata can be a bit much, at times; and there isn’t a lot of swashbuckling action… or wizard battles, even. But it’s a marvelous, gorgeous tale — one of my favorite YA fantasy novels of all time. Fun facts: The Dark Is Rising sequence continues with Greenwitch (1974), The Grey King (1975), and Silver on the Tree (1977). The 2007 film adaptation of The Dark Is Rising (US title: The Seeker), directed by David L. Cunningham, is a disappointment.

- Penelope Lively’s YA fantasy novel The Ghost of Thomas Kempe. When young James Harrison’s family move into an old Oxfordshire cottage that has recently been renovated, he discovers that the workmen have accidentally unleashed a poltergeist. His family blames the ensuing chaos — slamming doors, odd acts of arson and vandalism in the town — on him, at which point James befriends an exorcist. He discovers that the poltergeist is Thomas Kempe, a 17th-century sorcerer who considers the boy to be his new apprentice. Kempe is a difficult houseguest, one whose distaste for the modern world explains his acts of sabotage and destruction — cf. the sorcerer responsible for The Changes in Peter Dickinson’s The Weathermonger (1968). Those of us who’ve read the book as children know that Kempe’s truculence and unpredictability is unsettling; as an adult, I find the poltergeist more amusing. Most importantly, Lively is a beautiful writer whose evocation of the Oxfordshire countryside, and the dislocating eeriness of an encounter with a spirit out of time, is affecting. James, too, is a fun character, well able to look out for himself, and increasingly empathetic as he learns about Kempe’s history. Fun facts: Winner of the Carnegie Meda from the Library Association, recognizing the year’s best children’s book by a British subject. She would go on to win the 1987 Booker Prize for her adult novel Moon Tiger.

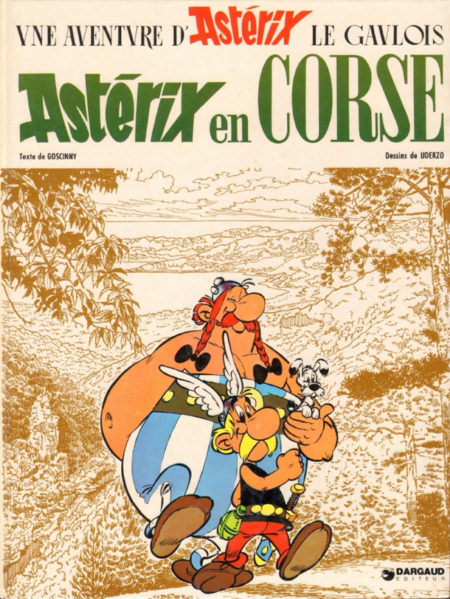

- René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s Asterix comic Astérix en Corse (Asterix in Corsica; serialized 1973, in English, 1979). When the indomitable Gauls, accompanied by friends from previous adventures — Petitsuix from Helvetia, Huevos Y Bacon from Hispania, Anticlimax from Britain, Drinklikafix of Massalia, Winesanspirix from Gergovia, among others — attack the Roman camp of Totorum, they free the Corsican resistance leader Boneywasawarriorwayayix. Asterix, Obelix, and Dogmatix accompany their new friend home, en route to which they encounter the usual crew of hapless pirates; the Corsican’s disgusting cheese (recognizable as casgiu merzu, a fermented sheep milk product containing thousands of live maggots) causes the ship to violently explode. Courtingdisastus, an ambitious Roman soldier, is sent to recapture the resistance leader; the corrupt Praetor Perfidius, meanwhile, plans to flee Corsica with his stolen loot. As per usual, Goscinny and Uderzo poke gentle fun at local stereotypes, including: Corsican laziness, long-simmering vendettas, grim glares, election fraud, old men sitting on benches and commenting on everything, and the maquis shrubland where armed resistance groups were known to hide. Napoleon is referenced frequently, particularly at the end of the adventure, when Boneywasawarriorwayayix (whose name, in the English version, is taken from a sea chanty about the Corsican emperor) strikes a Napoleonic pose. Fun facts: The 20th Asterix album, and the last Asterix adventure to be serialized in Pilote magazine, is the best-selling title in the history of the series. Subsequent adventures — Asterix and Caesar’s Gift (1974), Asterix and the Great Crossing (1975), etc. — would be published in album form only.

- Katherine Paterson’s YA historical adventure The Sign of the Chrysanthemum. In 12th-century Japan, battles between two powerful clans divide Kyoto, the country’s crowded, colorful capital city. After his mother’s death, Muna, an adolescent whose shameful name means “no name,” stows away on a ship to Kyoto in search of the father he’s never met. The only thing he knows about him is that he’s supposedly a great samurai… and he bears on his shoulder a chrysanthemum tattoo. Takanobu, a roguish but likeable ronin (masterless samurai), takes Muna under his wing. Muna gets a first-hand look at social injustice, and he is badly injured when he attempts to rescue Takanobu from a fire at their inn; worse, the girl he likes is sold to a house of ill repute. His fortune takes a turn for the better when he is taken in by Fukuji, a humble, but skilled swordsmith. When Takanobu reemerges, and asks Muna to steal a sword from the swordsmith, will Muna betray his master — even though Takanobu may be his father? I’m reminded of two of my favorite Sid Fleischman novels, Chancy and the Grand Rascal (1966) and Jingo Django (1971), although it’s less optimistic than these earlier efforts. Fun facts: Paterson is best known for her award-winning novels The Master Puppeteer (1975), Bridge to Terabithia (1977), The Great Gilly Hopkins (1978), and Jacob Have I Loved (1980). The Sign of the Chrysanthemum was her first novel.

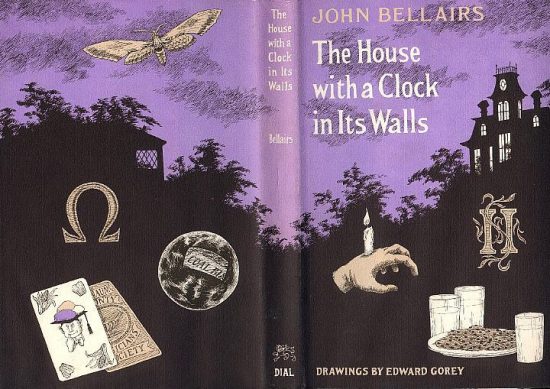

- John Bellairs’s children’s gothic horror adventure The House with a Clock in Its Walls. In the first of his many adventures, the recently orphaned Lewis Barnavelt moves in with his uncle, Jonathan, in a small Michigan town. Jonathan, a well-intentioned but not particularly powerful warlock, lives in a house formerly inhabited by Isaac and Selenna Izard, evil sorcerors who’d plotted to bring about the end of time. Before they died, Isaac had constructed a magical clock — hidden in the house’s walls — that ticks away as it attempts to pull the world as we know it towards its doom. In an effort to impress a new friend by demonstrating how to raise the dead, Lewis accidentally releases Selenna from her tomb; he must then enlist his uncle’s help — and that of their neighbor, Florence Zimmermann, a far more powerful good witch — in order to prevent Selenna from completing her husband’s dastardly work! Fun facts: The book, which was illustrated by Edward Gorey, was adapted into the 2018 Eli Roth film — starring Jack Black and Cate Blanchett — of the same name. Bellairs wrote subsequent Lewis Barnavelt adventures, including: The Figure in the Shadows (1975) and The Letter, The Witch, and The Ring (1976); other adventures in the same series were completed or written after his death.

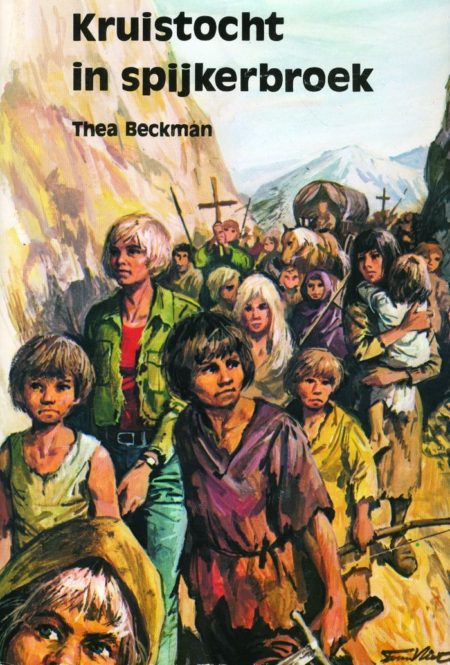

- Thea Beckman’s YA sci-fi/historical adventure Kruistocht in spijkerbroek (Crusade in Jeans). When Dolf, an Amsterdam teenager, volunteers for an experiment with a time machine, he expects to be transported to a medieval tournament of knights. Instead, he finds himself stranded in the 13th century, where he saves the life of a young Italian named Leonardo — whom the reader soon realizes is the brilliant mathematician later known as Fibonacci, who popularized the Hindu–Arabic numeral system in the West. Dolf and Leonardo join the Children’s Crusade — a real-life movement in which thousands of German and French youth attempted to reach the Holy Land, but instead met with great hardships, in the year 1212. Thanks to his 20th-century knowledge and perspective, not to mention a few “magical” devices such as a box of strike-anywhere matches, Dolf becomes a leader and organizer of the Children’s Crusade… and he’s able to save many innocents from bandits, epidemics, starvation, and slavers, as they trek across the Karwendel range of the Alps, toward Genoa and the sea. As a result of his actions, however, he is accused of witchcraft! The book takes a close look at the importance attached to social class and position, and the omnipresence of faith, in medieval times. Fun facts: Thea Beckman was a Dutch author of children’s books, best known for Crusade in Jeans and her post-apocalyptic Children of Mother Earth trilogy, in which soldiers invade a Greenlandic society led by women. Dutch fans of Beckman’s work have been known to complain that there hasn’t yet been an adequate English translation of Crusade in Jeans.

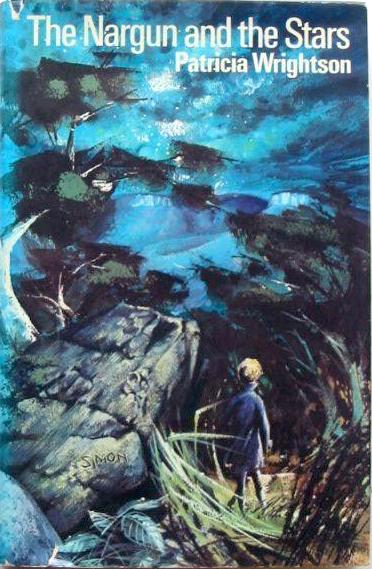

- Patricia Wrightson’s children’s fantasy adventure The Nargun and the Stars. Simon Brent, an adolescent orphan, is sent from the city to live with relatives on a 5000-acre sheep ranch in the remote Hunter Region of New South Wales, Australia — think of the first act of the 2016 New Zealand film Hunt for the Wilderpeople. While getting to know his new family, and exploring his new surroundings, which Wrightson, one of Australia’s most distinguished children’s authors, describes poetically, Simon meets a potkoorock. The mischievous swamp creature warns him that the Nargun — a fierce half-human, half-stone creature — has been awoken after a millennial sleep (“while eagles learnt to fly and gum-trees to blossom; while stars exploded and planets wheeled and the earth settled”) by humankind’s digging machines, and has slowly made its way into the Hunter Region. There is no European mythology, here: The Nargun is a creature from the mythology of the Gunaikurnai, an Indigenous Australian nation whose territory occupies most of present-day Gippsland and much of the southern slopes of the Victorian Alps. Can Simon and his family preserve the land, protect the whispery cave Nyols and the rustling tree Turongs, and stop the predatory Nargun’s advance on their farm? Fun facts: The Nargun and the Stars was among the first books for children to draw on Australian Aboriginal mythology. Wrightson’s story was made into a mini-series for television by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation; it was screened in 1981.

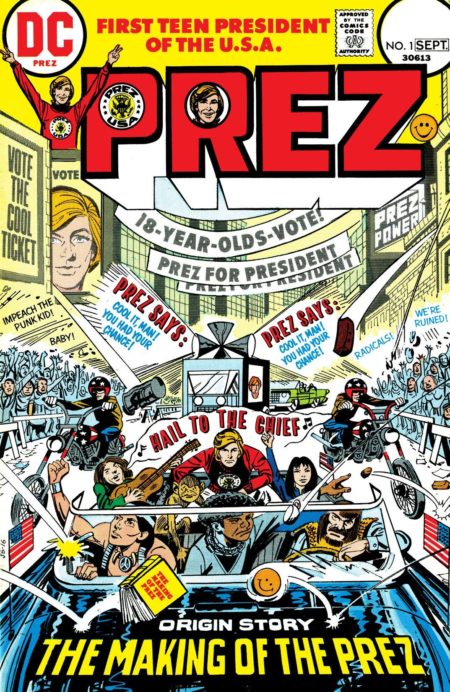

- Joe Simon and Jerry Grandenetti’s political adventure PREZ (1973–1974). In a fine example of the first-time-as-comedy-second-time-as-tragedy trope, the short-lived comic Prez should be read as an un-cynical, though still bizarre version of Wild in the Streets, the 1968 youthsploitation movie in which a teenage pop star and his multiracial band mates move into the White House… and chaos ensues. Recruited by a shady political boss to run for the Senate, Prez Rickard campaigns on his own terms and is elected president. He selects Eagle Free, a young Native American, to be director of the FBI, his sister to be his chief of staff… and his mother to be vice president. The series was canceled after four glorious issues in which Prez battles a right-wing militia, demands strict gun control, brings peace to the Middle East, survives an assassination attempt, and encounters (why not?) evil chess players and a werewolf. I’d vote for him! Fun facts: In 2015, DC launched a miniseries under the title Prez about a teenage girl named Beth Ross who is elected president via Twitter in the year 2036. Over the years since 1974, the original Prez character has surfaced in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series, in Supergirl, and elsewhere.

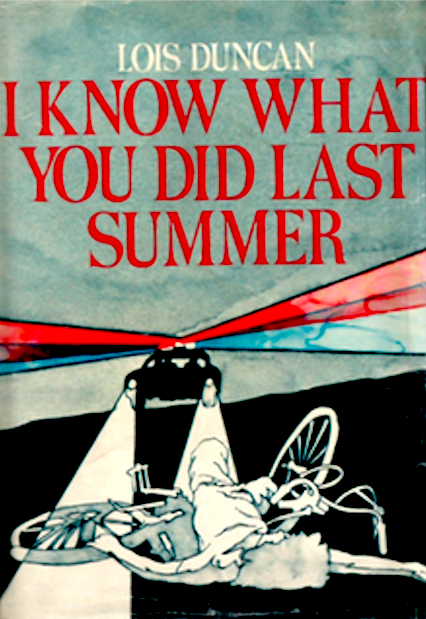

- Lois Duncan’s YA suspense thriller I Know What You Did Last Summer. Julie James, a red-headed cheerleader who has just graduated high school in Silver Spring, Maryland, receives two letters in the mail that will change her life. One is her acceptance letter to Smith College, which delights her mother — who’s worried about how serious her daughter has become since the previous summer. The other letter reads: I KNOW WHAT YOU DID LAST SUMMER. Julie meets up with Barry Cox, a college freshman and jock, and his glamorous girlfriend Helen, who has dropped out of school to work in television; they discuss a pact they’d made, the previous summer. Then Ray, Julie’s ex-boyfriend, who’d moved out of town, returns — and we discover that the four teens are haunted by a tragic accident in which a child was killed. Soon, Barry is shot — and possibly crippled — and he claims that he was lured into an ambush by Helen. What’s going on? Can anyone be trusted? Who will be attacked next? We can see the beginning of darker, more troubling Seventies-style YA lit beginning right here. Fun facts: Duncan was a pioneering figure in the development of young adult fiction, particularly in the genres of horror, thriller, and suspense. The 1997 slasher film adaptation of I Know What You Did Last Summer, starring Jennifer Love Hewitt, Sarah Michelle Gellar, Ryan Phillippe, and Freddie Prinze Jr., wasn’t very good — but it has become a cult classic.

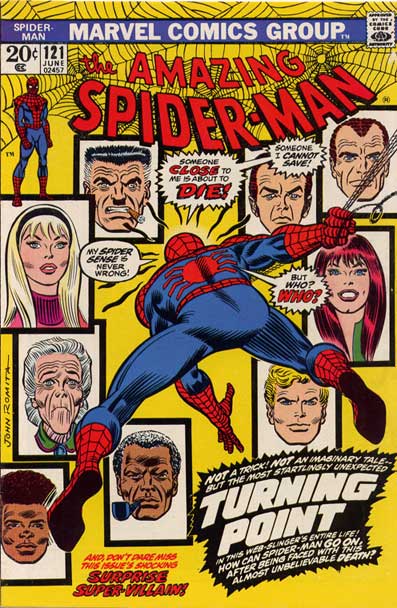

- Gerry Conway, Roy Thomas, and John Romita Sr.’s “The Night Gwen Stacy Died” story arc in The Amazing Spider-Man #121–122 (June–July 1973). If the cultural era known as the Fifties ended in ’63 with the assassination of John F. Kennedy, then the Sixties ended in ’73 with the death of Gwen Stacy. Harry Osborn, Peter Parker’s best friend, is addicted to drugs; parental grief causes Harry’s father, Norman, to snap out of his fugue state and remember not only that he is the Green Goblin, but that Peter Parker is Spider-Man. The Green Goblin kidnaps Peter’s girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, and lures Spider-Man to a New York bridge — then hurls Gwen off of it. Does Spider-Man’s attempt to save Gwen kill her? He certainly believes so. Readers were shocked: Important characters were not killed off; and superheroes did not fail in such a disastrous and tragic way. This story arc was a watershed event not only for Peter Parker. It marked the end of the Silver Age of Comic Books, which had kicked off in 1954 with the introduction of the Comics Code Authority; and it paved the way for the Bronze Age, which began in 1974 with the first appearances of Marvel’s dark, gritty characters Wolverine and The Punisher. Fun facts: During the Bronze and Modern Ages of Comics, the wives and girlfriends of superheroes began to drop like flies. In 2001, The Comics Buyer’s Guide revealed that within comics fandom this disturbing trend was known as “The Gwen Stacy Syndrome.”

BEST SIXTIES YA & YYA: [Best YA & YYA Lit 1963] | Best YA & YYA Lit 1964 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1965 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1966 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1967 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1968 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1969 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1970 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1971 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1972 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1973. ALSO: Best YA Sci-Fi.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.