OFF-TOPIC (4)

By:

April 12, 2019

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This month, a three-person’d reflection on fluid identities, and the banks that bound or give way to them, as told in transformative works for stage, sound, and painted surface…

We’ve all become the audience of our own story, but that still makes us unknowns for 15 minutes to life. The protagonist of Kim Katzberg’s apocryphal autobiography Dad in a Box is searching for the woman behind the screen, but her attention is divided into the myriad of personalities she either assumes or has imposed upon her. Self-doubting fringe theatre artist “Kim” is attending an improv class to enhance her skills’ market-value, when the sudden terminal illness of her complicated father causes her to face how much she and her family have been making up all along. Disguising her pain in a series of macabre sketches — a serial-suicide-attempt sitcom; local-TV ads for a custom dirge-singer — she also takes on the personae of her damaged siblings, step-mother, and the abusive, magnetic, addict dad himself, as well as a random passenger on the plane-ride home, sundry therapists and self-help saviors, and the unimpressed improv instructor. From a single angle Kim performs the role of judge, jury and condemned, even though it’s dad’s funeral, not hers. Back-projected fantasias of Kim’s characters and of dad’s fav entertainment (drecky women’s-prison flicks) box her in amongst the many social mirrors that don’t care who’s looking at them, and stark house-lighted interludes drop the screens to stress-test how she can stand on her own. A cathartic closing rant (with a perfect existential punchline right after) shows us how the healing is only beginning as a lifetime ends.

Katzberg is a phenomenal shapeshifter of attitudes and inner lives, and the multimedia barrage and emotional cacophony is orchestrated well by director Raquel Cion. Dad in a Box shows many faces to the world, and as no stranger to family trauma, psychic withdrawal, and dead junkie loved-ones myself, I recognized every one. At this writing the show’s first run has less than a week to go, but poses questions one could spend the rest of their life on; I went over just these three with Katzberg after opening night:

HILOBROW: The play addresses dissociation frequently. Is dramatization the opposite of this retreat from difficult reality? “Kim” seems anxious about whether it’s just another abstraction of feeling, but it seems to me it can be an insistent attempt to see things from within the other people she portrays?

KATZBERG: I make theater to communicate what I can’t express in my everyday life. Characters have always been a safe container for me to go wild, be bold and explore what’s underneath the surface. I feel most in my body when I’m in character. The direct address was scariest for me because I’ve never been just myself onstage. I was worried that I would disassociate and I wouldn’t be interesting to watch. I would say yes, dramatization, and this play, is my attempt at expressing what is real for me around my father’s death. When I’m talking about what’s real, I’m not dissociated.

HILOBROW: I’ve found that one way toxic loved-ones take up residence in your head is by transferring the desire to “win” when in fact the only victory is walking away, breaking the stare so to speak. Is the Kim character’s closing speech an illusory last word or a way of truly ceasing to listen to that voice?

KATZBERG: I have issues to confront with my Dad, within myself, and the ending is about how much work I still need to do. I was in the process of facing some of those things, like his alcoholism, my codependency and my fear of him. But he had to go and die on me! (I’m joking.) I have a long way to go until I come to terms with my troubled relationship with him, and I wanted the final speech to be both a release for “Kim” and portray how disturbed the relationship still is for me even though he’s gone.

HILOBROW: I have to assume that a lot of this play is true to your life — if so, does having to make that “final” declaration many nights in a row feel like catharsis or re-injury? (Asking for… well, me, and all my friends :-).) Does the emotional arc of this show put the pain away in a box, or does it reflect a need to keep reopening it just to make sure what you locked up is still in there?

KATZBERG: Yes, it is very true to my life. I made this play to connect with my Dad, something I struggled to do when he was alive. It wasn’t until after the first three performances, when I got a 24-hour stomach bug and had to just be home with myself, that I felt acute grief as a result of the subject matter of the show. Reliving his death is opening me up and connecting me to my Dad. Reflecting back, I think I initially wrote the show to avoid the grief, but of course because of the show, I am now feeling the grief. The structure of the show gives a form to explore the grief safely, and my director Raquel helps me with that.

To live your own history is to wake up from someone else’s dream. In Camellia, a testament of her lucid trances, the artist who knows herself as Dia Luna walks the primordial deserts and lush farms and concrete crypts of America as one simultaneous plane, threading together its collective soul behind every stone and stalk, around every corner. “This tree winds roots around my backbone/thank heaven for the stories I’ve grown”; her bloodstream travels through the fertile fields and she will harvest her future self: “vision pulls you to the seams of the landscape/closer and closer to sowing your escape”; growth is transport, across seasons or centuries. The path can take what course it will, and peoples can go underground, “crawl in the tunnels of my infinite mind,” but the deluge comes and bears us up, “birthed from the watery beds/of your own mother’s flesh.” Lies will stamp the ground of myth (“I’m a cowboy now”) but the green chaotic earth has soil on its side. Cross-border transmissions of false faith drift into the mix, found sounds of some radio evangelist’s ghost going lost again as a private hymn rises from laborers to their loved ones, those who stitched the land with seedlings and sutured it with rails, destiny sowed as amber fields and reaped as steel, binding us and bearing us away. Ancestors possess ethereal machines and Dia Luna’s unadorned voice hovers in a mist above Tomas Deltoro-diaz’ transcendent technology and tide of tones and rhythms streamed in from many lineages and landscapes. Every voice she has is heard, and you feel your own soul echo.

I went to the oracle for brief answers and the right next questions, in her earth name, Andrea Diaz…

HILOBROW: Nature’s growth is like a reverse burial; we’re transient as individuals, but can we feel immortal collectively?

DIAZ: Certainly. There are archetypes that have always belonged to humans and will always be an embodiment of our collective Soul, regardless of time. Music and other forms of art give these archetypes shape and display the timelessness and spectrum of human emotional experience.

HILOBROW: In these songs there’s a sense of continuum between inert soil and ephemeral consciousness and all the organic beings in-between. Are we searching in vain after eternity when we could be observing fullness now?

DIAZ: Not necessarily. I think the desire to commune with the eternal can be the very thing that eventually opens us up to the beautiful (and often terrifying) experiences of temporality — blood, dust, and all.

HILOBROW: The material and the mystical have long been seen to clash — and sometimes shown to merge — in the otherworldly mechanics of electronic music. The sound here is both very physical and sublimely transcendent… is everything a link to what’s beyond us, if you can sense how to direct it?

DIAZ: My cousin and engineer, Tomas Deltoro-diaz, did an excellent job in transforming my conceptual direction into specific sonic decisions. From my perspective, everything can be a link to what’s beyond us as long as we have the intuition, patience, and the willingness to venture into the unknown.

HILOBROW: The tunnels in “Wild” make me think of how people escape across (under) borders, or Persephone sojourning in the shadow of death for a season, and “Fields” of course puts me in mind of everyone who tends lands and builds lives, only for others to try to cut down…how specific are your thoughts and sources when writing these dreamlike scenarios?

DIAZ: My sources on Camellia were a mixture of fact and fiction, experience and imagination. Some of the songs, like “Wild,” have a more emotional starting point, growing from my personal experiences of confusion and trauma. Some songs, like “Fields,” grew from stories about my family, in this case my grandparents on my father’s side, who migrated to California from Mexico and worked on the land. Collectively the songs became a poetic way for me to use these images, dreams, and ideas to create a specific coming-of-age narrative.

HILOBROW: The raw voice plays a major role, be it the breaths that open “Acres” and “Wild” or the unadorned vocal line of “Will” and “Cowboy” — the body is the original instrument and may be the final one; is it important to stay grounded there?

DIAZ: Definitely. In the era of perpetual scrolling and infinite screen time, we forget the body has its own intelligence and its own way of being. The body connects us to the earth. It tempers the hubris of the mind by reminding us that we too, outside of our likes, our ambition, and our success, are just delicate creatures trying to survive. This sense of humility is especially important now in the face of climate change and other factors shifting the kinds of physical and emotional landscapes people occupy.

(other incarnations on HiLobrow: here)

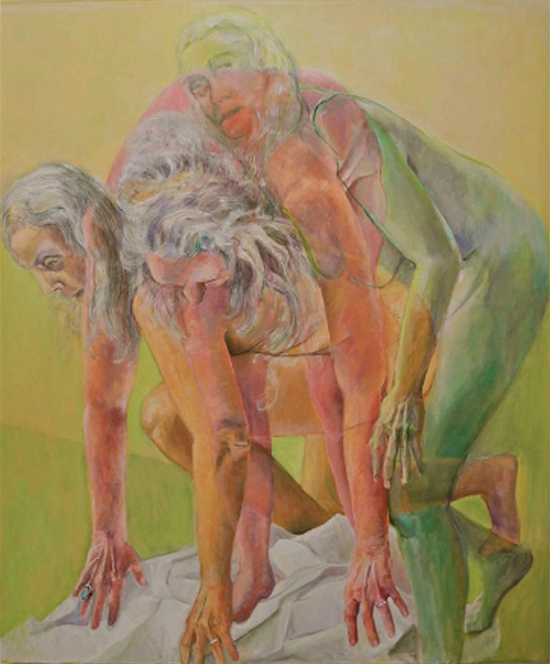

For six decades, Joan Semmel has been changing before her own eyes. Her identity often effaced to the viewer, she employs her body as a prism to shine sight on every person we each could be. Seen from her own point of view and thus anonymous, inclusive, her skin blue or green, the contours of her body a landscape, her face blurred or multiplied or unseen behind a camera, Semmel’s privacy is uninvaded while our subjectivity is engaged.

First scandalous for scenes of sex in the early 1970s (which ran into trouble not for the erotic content but because people took the couples’ orange and yellow or pink and green skin colors to connote interracial love, wtf), she was then first renowned in the mid-’70s for her surreally foreshortened nude self-portraits, based on photos taken from the top of her body. In a culture of exploitation, these images insisted on no one’s gaze but hers, though beyond that, the bodies could be anybody.

The female figure and soul that cannot see you, and the layers you can’t see, were a central theme ever after, always in a discussion not just between the canvas and the observer, but also with the absent embodiment of an era’s cultural context. Her early-1980s mash-ups of vibrant gestural figure studies with literal photographs, and later-’80s images of bodies in actual landscapes, transferred to intimate scale the bold brushstrokes with which macho “neo-expressionist” painters were then asserting dominance over the art world. Her naturalistic scenes of women in gyms and locker-rooms reflected on the physical obsessions of the same period, while serving as an answer-single to time-worn harem motifs. Her strangely animate studies of mannequins in the 1990s sounded eerie echoes of piled bodies and disposable de Milos, in a decade where genocide made a comeback and goddesses tried to.

Confronting the camera in both its objectifying stare and its supposed usurping of her traditional medium, Semmel incorporates its possibilities back into the painted canvas’ organic DNA; stroboscopic multiple self-images from the Aughts and 2010s suggest a scope of personality that can only be partially captured, and a portrait of quantum possibility. In her show just completed early this year, the planes and shapes of radically flat (or single) color lock in around her form like the sections of a stained-glass window from some alternate, woman-centered and sex-positive spiritual tradition; though often articulated with her sumptuous sense of mark and texture, the spaces acknowledge the surface-depth of paint like her earlier works welcomed the skewed perspective of photography. From these immaterial backdrops her honest form lives out all the more emphatically; you can’t injure her, and since a half-century before Photoshop, she’s been un-retouched. “I wanted not to be shamed for having desire, I wanted not to be shamed for getting old,” she once said on the occasion of a career retrospective at the Bronx Museum; in this culture there is still little invitation for an autonomous woman to be heard from at all, let alone seen for this long; nevertheless, she will continue to picture it.

Images, top to bottom: A shot from the Dad in a Box trailer video by Roque Nonini, a production shot by Maria Baranova, another from Nonini’s video, and another production shot by Baranova; Camellia cover; a shot from Dia Luna’s “June” video; and two portraits of Andrea Diaz (the first by Camilo Fuentealba, second uncredited); five paintings by Joan Semmel: Secret Spaces, IntimacyAutonomy, Rack, Triple Play, and In the Green

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE