STUFFED (33)

By:

March 23, 2019

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste. STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s collection of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

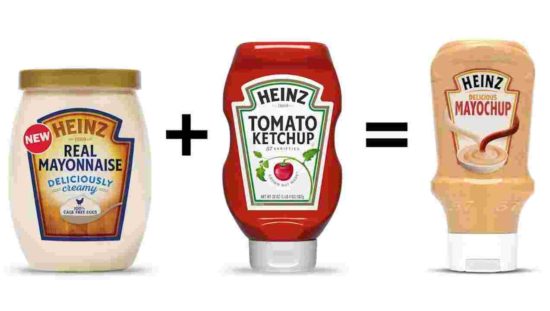

While there may never be a bad time to talk about mayonnaise-derived sauces, Heinz’s launch of mayochup (#mayochup) makes this an especially good time. Is it really necessary — my brain says no, but my heart and history say “sure”.

We have always wanted red mayo (#redmayo) and this is just another iteration of a centuries-old love. Is it more self referential, needlessly ironic, and contorted than usual? Of course, but isn’t that who we are? How else to market a product that is two things that everyone already has in their refrigerator, mixed together?

And what of Russian and Thousand Island? Are they to be cast aside before we even figure out what the difference between them is? Is mayochup just dumbed-down sauce andalouse (Belgian fry sauce with tomato and mayo)? It doesn’t matter — condiments wait for no one, so I salute Heinz for their pluck, latecomers to the mayo wars though they may be. But some deep background on this new name for an old condiment would be helpful before we paint it all pink and leap into a mayochup future.

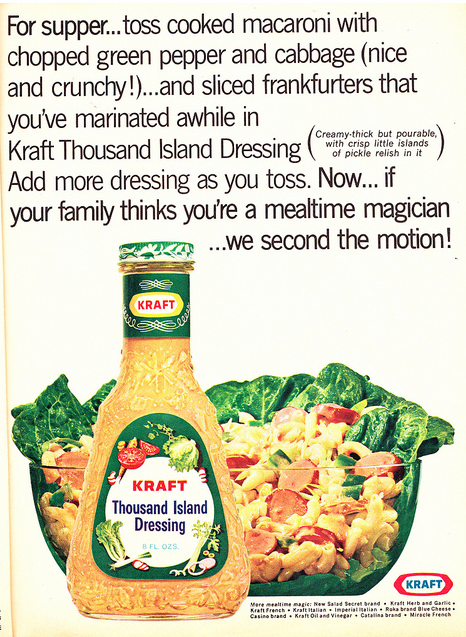

Even before mayochup burst, Kool-Aid Man-like, through the brick wall of our condimental hearts, we have had a love affair with mayo mixtures — especially Russian and Thousand Island (or Islands? Only recently did we settle on the singular) dressings. Much ink has been spilled trying to sort, separate, and suss out what the difference is between them, where they came from, and how Thousand Island emerged victorious, more or less (at least until mayochup catches on) from their brutal internecine conflict.

Are they almost the same or meaningfully different? Are the “islands” pickle bits? Why is is called Russian? Because it’s pink(o)? Was it made from sour cream or horseradish? Include caviar? Did it fall out of fashion during the Cold War? Was it all the fault of McDonalds and their not-so-secret sauce? What, in short, is going on with these ubiquitous yet mysterious dressings?

The earliest mention of both Thousand Island and Russian date to the same period — around 1910 — and it has always been assumed that they developed concurrently. This makes sense since it was a golden age of salad — hotels and restaurants were first exerting their food influence in this period and inventing salads in a spiraling salad arms race (caesar, cobb, chef, crab louie, Waldorf etc.). It was also a popular time for red foods both naturally and unnaturally colored (in 1878 the food coloring amaranth dye, later called red dye no. 2, was invented). These dressings would have filled a need for a red-hued dressing to put on all of the new salads being churned out by the Salad Industrial Complex. It was also, in general, a time period where products that had been made at home or in small batches were starting to be produced in industrial quantities.

People have remarked over the years at the differences in the recipes for Russian and Thousand Island, but most of them are cherry picking — the actual recipes are very similar and contained mayo, chilli sauce, and/or ketchup, and usually something else. People over the years have claimed that hard-boiled eggs are in Thousand Island and not Russian, or that TI has ketchup and Russian chilli sauce, but it’s common to see both those rules broken. Thousand Island does tend to have more junk in it — chives, relish — that you don’t see in Russian, and it often had Worcestershire or anchovy sauce (though Russian recipes sometimes include Worcestershire).

Even the chilli sauce and ketchup weren’t as far apart as they seem: Chilli sauce of the time was mostly tomato with some added cayenne, more similar to tomato ketchup than sriracha or Cholula. Tomato ketchup itself had only but lately come out on top during the great ketchup wars of the 19th century, where it bested walnut, mushroom, oyster, and a host of other half-remembered ketchups to be the one true ketchup that we know so well. It is always good to remember that many of these ingredients were more fluid, more in flux than we might suppose from the staid bottles we see in the supermarket.

Both dressings sometimes had whipped cream (!), which I have to (need to) assume was more often sour cream in the wild, but because sour cream had only just arrived in the U.S., it was expressed as whipped cream in cookbooks, and once in a while you see horseradish in Russian. The most striking difference — and the origin of Russian’s name — is that early on, it often had caviar in it. Though it would have made sense for the caviar to be the islands in Thousand Island, this never seems to have been the case.

As to the origins of the dressings themselves, they are a jumble. A guy named Colburn in Nashua, NH supposedly invented Russian around 1910-13 and produced it for sale (Thomas Rector reportedly built an emulsifying machine out of a milk homogenizer around the same time and produced Russian, tartar sauce and mayo) and, Thousand Island, the story goes, was invented in the Thousand Islands region of New York State. The inventor of the latter is alternately a chef on a luxury yacht caught short of ingredients and forced to improvise (a much repeated story about the origins of mayo itself is a version of this trope) — sometimes the yacht was George Boldt’s and the chef was Oscar from the Waldorf-Astoria hotel — or an actress on a yacht who was friends with George Boldt and brought it to the Waldorf, or, even more improbably, it originated at the Blackstone Hotel in Chicago. Recently a recipe apparently postmarked 1907 with a similar list of ingredients (but not called Thousand Island) surfaced in the region and has been hailed as the actual origin recipe.

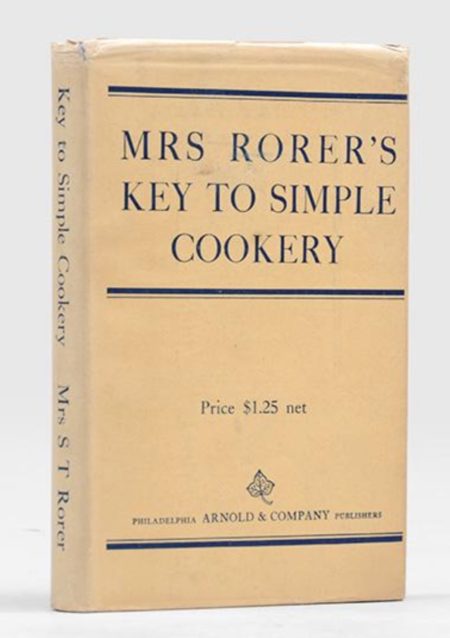

Whatever really happened to muddle these two together happened very quickly because a 1912 community cookbook from Illinois is already giving recipes for “Russian or Thousand Island Salad Dressing” and Mrs. Rorer’s popular 1917 cookbook Mrs. Rorer’s Key to Simple Cookery suggests making Russian dressing by adding caviar to Thousand Island. According to data at the NY Public Library menu project (which is incomplete but interesting), Russian first appeared on a menu in 1914 and peaked in 1950. Thousand Island first appeared in 1918, passed Russian in popularity in the early 1950s and peaked in 1981.

We all like a story, and stories with a clear beginning are easier to tell and simpler to remember. Food stories tend to be messy, poorly documented things — at best they take place off the radar and away from written histories and, often, even written cookbooks. It’s why people can lay claim to culinary inventions like Russian dressing or Thousand Island and have the stories repeated for decades — it’s hard to disprove them and the arc of a made-up story is usually more appealing than the ambiguity of a real one, especially when it is engaged with capitalist fantasies of brilliant men inventing things and selling them. So while, by the same token, it is difficult to demonstrate that these origin stories are complete fabrications, here is why I believe that to be the case.

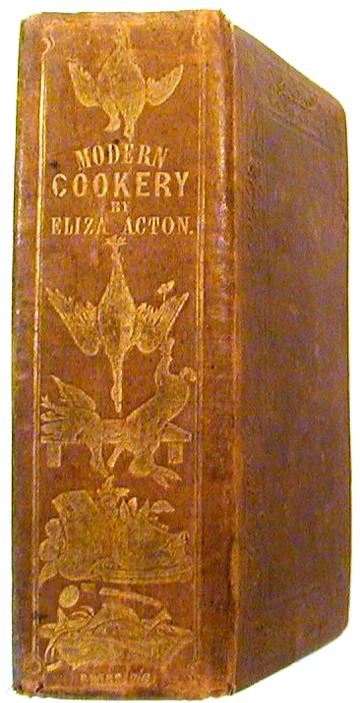

In the mid-19th century, when the vogue for red foods that would lead to the discovery of food coloring (mauveine in 1856, amaranth in 1878) was just getting going, the popular cookbook author Elizabeth Acton published a recipe for “Red or Green Mayonnaise Sauce” in the 1860 edition of her much reprinted Modern Cookery, In All Its Branches; Reduced to a System of Easy Practice, for the Use of Private Families.; In a Series of Receipts, which have been Strictly Tested, and are Given with the Most Minute Exactness. The green, colored with spinach, never really caught on, but the red, colored with lobster roe (often called lobster coral) was a minor hit. It pops up over and over again in recipes for the next 50 years. This red mayonnaise meandered through the decades until the turn of the century when people began coloring their mayo with tomato, a cheaper and far more ubiquitous colorant — a recipe for tomato mayonnaise in an issue of The Delineator from July, 1902 described the concoction as “comparatively new.”

The inflection point for this red mayo is found in the 1910 Settlement Cookbook (and reappears as this seminal cookbook was reprinted) where red mayonnaise is first given as tomato but suggests lobster roe as a substitute. The 1916 Anglo-Chinese Cookbook goes a step further, suggesting tomato, lobster coral or carmine (the red dye made with the cochineal insect) for coloring. By 1920 the Children’s Mission Cook Book gives a recipe for Russian dressing as “Add Russian caviar to Thousand Island Dressing” and by 1922 in The Castelar Crèche Cookbook Los Angelinos had enlisted either Thousand Island or Russian with capers, chili sauce, and “1 small box of caviar” for their Avocado Cocktail, a dish that seems to have been but lately invented by the California Avocado Association, which was founded in 1915.

In fact, the dressings do seem to have undergone some changes as they traveled to California, though they were similarly muddled on the journey. The Hotel St. Francis Cookbook (1919) includes recipes for both, but they are nearly identical (mayo, french dressing, olives, pimentos, chili sauce — the only difference was that Russian also had Worcestershire sauce).

The kernels of what we now call Russian and Thousand Island were out there in the world for at least 50 years before someone “invented” them. If that seems like a lame origin story, it’s only because we’ve been trained to think that way — some guy invented this, filled this need, got rich, endowed a museum, or blew it all on whiskey and dice. Some guy.

The world is big and various and our foods a wild, sprawling mess — shouldn’t we embrace that instead of reductive folk tales? Isn’t it wild that it all started with lobster roe? Who would have thought? Lobster roe: that is pretty cool. Or it started with something earlier and red that I didn’t turn up — something that led to lobster roe, which branched into caviar (Russian branch) and tomato (Thousand Island branch). Mayonnaise itself, after all, hung around Spain and Provence for a thousand years as aioli/allioli before it caught on in 18th-century France. So it’s hardly surprising that red mayo would do the same.

A version of this essay appeared in the Winter 2019 Book Club of California Quarterly.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.