Listen, Hollywood! (3)

By:

March 18, 2019

One in a series of 10 posts suggesting novels (from Josh Glenn’s BEST ADVENTURES series) that really ought to be adapted for the big screen.

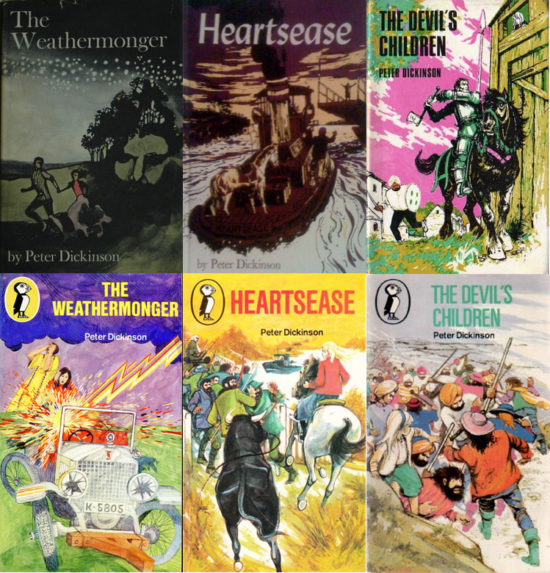

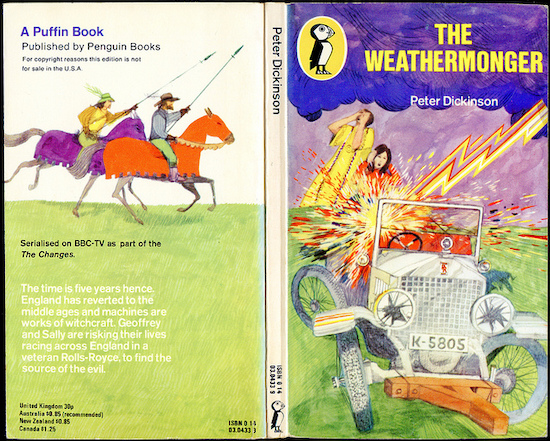

Peter Dickinson’s YA fantasy trilogy, The Changes — The Weathermonger (1968), Heartsease (1969), and The Devil’s Children (1970) — are included on my lists of the Best Adventure Novels for each of their respective years.

With nothing meaningful to say about our future, we’ve retreated into the falsehoods of the past, painting over the absence of certainty at our core with a whitewash of poisonous nostalgia. The result is that Britain has entered a haunted dreamscape of collective dementia — a half-waking state in which the previous day or hour is swiftly erased and the fantasies of the previous century leap vividly to the fore. — Sam Byers, New York Times

Nearly three years after the Brexit vote and deep into the departure process, we can agree that Brexit was always about xenophobia, and a belief in a lost, past greatness — nothing more. Dickinson’s Changes trilogy could not be more timely!

When a mysterious enchantment settles over England, many of its white, working-class inhabitants rapidly revert to an ignorant, xenophobic way of looking at the world. They become technophobes, persecute anyone who isn’t perturbed by machinery as witches, and return to farming and an old-fashioned life. Once nearly all of those who are unaffected — in particular, all immigrants — have fled England for the continent, the country makes (to coin a phrase) a hard Brexit… from the 20th century. The rest of the world, however, is unaffected. What’s going on?

SPRING 2020 UPDATE: Um, “British 5G towers are being set on fire because of coronavirus conspiracy theories.” Yeah, this too is predicted by the Changes trilogy. WTF?

Elevator pitch: A trilogy of movies, or a TV series, set in a modern-day Britain that has mysteriously reverted to an old-fashioned, and xenophobic way of life. Caught up in the Changes that caused adults to destroy all machinery, our heroes are English adolescents determined to survive (Nicky and various young Sikhs, in The Devil’s Children), escape (Margaret and Jonathan, among others, in Heartsease), and get to the bottom of the mystery (Geoffrey and Sally, in The Weathermonger). Our plucky young heroes are challenged not only to rely on their wits, but to champion progressive values in a world turned ultra-conservative.

First installment:

Dickinson wrote and published The Changes in reverse order; so The Devil’s Children is actually the first book in terms of the trilogy’s chronology.

Here, we witness the Changes through the eyes of a 12-year-old Londoner, Nicky. Overnight, her parents and every other white adult in the city seem to go mad — smashing up their televisions and refrigerators, cars and buses, and every other sort of machine. There are increasingly violent riots, as England’s white population turns against non-white minorities, who are forced to fight and flee. There is a mass exodus from London, as those unaffected leave the country for the Continent, and those affected leave the city for the countryside, where they revert to a pre-modern way of life in small villages.

Historical note: In the 1930s, Oswald Mosley, the great exponent of economic autarky [that is, economic independence or self-sufficiency, on a national level], wanted radical national protection and the stimulation of home demand. His British Union of Fascists (BUF) condemned what it saw as Britain’s capitalist cosmopolitanism, and repeatedly demanded increased domestic food production and the manufacture of oil-from-coal. During the Second World War, it was the left that offered a nationalist critique of globalized British capitalism. In “England, Your England” (1941), George Orwell argued that the monied class “sat, at the centre of a vast empire and a world-wide financial network, drawing interest and profits and spending them – on what?… the empire was underdeveloped, … and even England was full of slums and unemployment.” In the past few years, the green movement has advocated national self-sufficiency in food and energy, not to mention the concept of the “food mile” — and the Brexit-voting public was nostalgic for a national economy. There are also budding ideas of local self-sufficiency, such as the “Preston model,” pioneered by its city council, of building “community wealth” by encouraging public authorities to procure from local suppliers. A June 10 (2020) item in The New Statesman suggests that Britain is entering a “new age of autarky.”

Nicky is affected by the Changes herself, to some extent — machinery makes her uneasy, though not violent. She does not participate in the chaos, and is left behind. When a group of Sikhs — American and English movie audiences may be familiar with fictional Sikhs from The Darjeeling Limited, Inside Man, The English Patient, and Bend It Like Beckham — travels through the city en route to finding a safe, permanent home in the countryside, Nicky joins their caravan.

Historical note: In 1967, a Sikh bus driver, Tarsem Singh Sandhu from Wolverhampton, a city in the West Midlands, was sacked from his job after he refused to remove his turban and shave his beard. Some six thousand Sikhs from across England marched in protest. Wolverhampton MP Enoch Powell’s 1968 address to the General Meeting of the West Midlands Area Conservative Political Centre, which became known as the “Rivers of Blood” speech, defended discrimination on the grounds of race in certain areas of British life, particularly housing, and claimed that England was “heaping up its own funeral pyre” by permitting mass immigration. So Dickinson’s novel should very much be seen as a commentary on the moment.

English actress Millie Bobby Brown, of course, would be perfect as Nicky — though she’s already a bit older than Dickinson’s character.

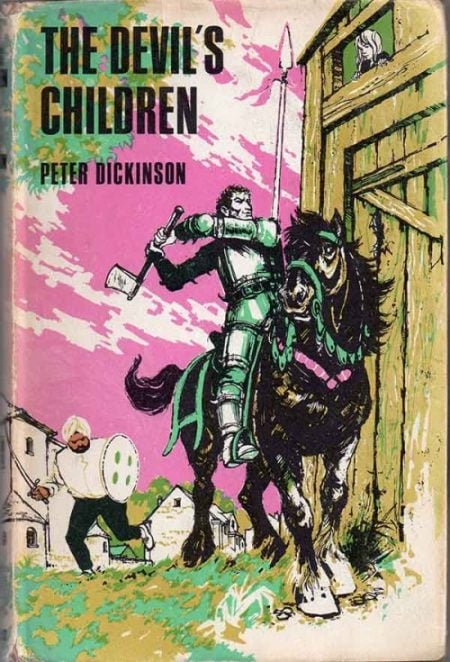

In post-Changes England, the Sikhs are considered “the devil’s children” — feared, but also respected for their arcane skills. Nicky learns to love and respect her adopted family, who prove to be courageous, smart, and adaptable. She grows particularly close to the Sikhs’ matriarchal elder, to whom everyone defers. After some adventures, the group eventually establishes themselves in a new home near a farming community — where they set up a forge and begin repairing broken plows, pitchforks, and so forth. Nicky acts as a go-between. The village’s Trump-esque leader is a fat, hate-mongering populist; other members of the community are a bit more reasonable.

Although their new neighbors are highly skeptical of the Sikhs, when a group of raiders attacks the community, Nicky and her brave friends rush to their rescue. There’s a climactic neo-medieval battle scene….

Is it too much to hope that Waris Ahluwalia, from The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, Inside Man, and other films, might portray one of the Sikhs?

Second installment:

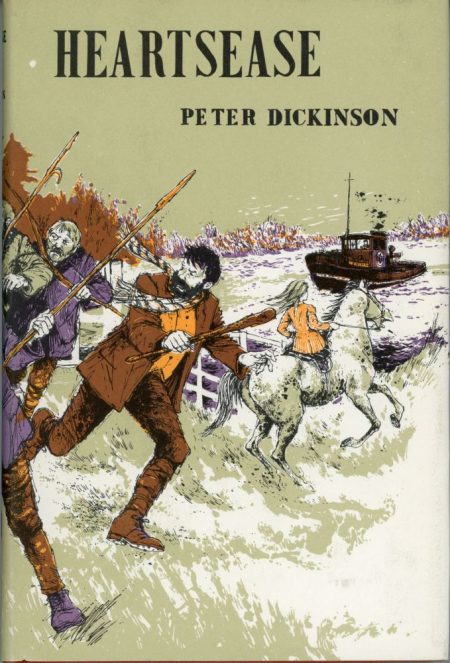

Heartsease takes place a couple of years after the events of The Devil’s Children; it is less momentous, more claustrophobic and brooding, than the other two series installments — though there is plenty of action towards the end.

The book takes place in a small town near the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal, in the west of England, as well as on a derelict tugboat abandoned during the Changes. The post-Changes new normal is farming and subsistence living, surrounded by the rusting relics of the 20th century. Anyone who dares to tinker with machinery is persecuted as a witch. As in the previous installment, there’s a particularly hateful village leader; the rest of the community goes along with the leader’s agenda, but we’re given to understand that they’re not uniformly horrible people. Unfortunately, nobody is willing to speak out against the village’s leader, which is why the children must plot behind their elders’ backs. Which is a very British trope, indeed — cf. Thomas Hughes’s Tom Brown’s School Days, E. Nesbit’s Bastable and Psammead series, T.H. White’s The Sword in the Stone, The Famous Five series, the Harry Potter series….

One such “witch,” who is rescued by three children in a Cotswold village, turns out to be Otto, an American intelligence agent who has bravely parachuted in to investigate England’s mysterious “Changes.” Otto is badly injured in the book, which doesn’t give him much to do besides being cared for. For the adaptation, I imagine him (or her) training the children how to use guerrilla tactics in order to pull off their nearly impossible feat: relocating the injured Otto to a derelict tugboat moored in a nearby canal, getting the tugboat operational, and figuring out how to operate the canal’s system of locks en route to the ocean. Tom Hardy? Daniel Kaluuya? Charlie Hunnam? Emilia Clarke?

In the novel, horse-loving Margaret (Emily Carey? Maisie Williams?) reluctantly helps her machinery-obsessed cousin, Jonathan, and the family’s servant, Lucy, and Lucy’s mentally disabled brother, Tim, succeed in their quixotic mission. She’s the least resourceful and dynamic character; but her desire to remain at home, to work to improve England instead of fleeing, adds dramatic tension.

Can Margaret and the other youngsters figure out how to operate the canal’s locks, and spirit Otto to safety — while contending with feral dogs, a violent bull, and superstitious villagers? And, when the moment comes to decide, will Margaret join the group’s flight to France? PS: There’s a charismatic horse in this story, too.

Third installment:

The Weathermonger, which was published first, is chronologically the series’ final installment. It opens with a terrific set-piece: A teenage boy, Geoffrey, snaps out of a fugue state — in which he’s been for years — and discovers that he’s been marooned on a concrete island in the harbor of an English village, along with his younger sister. He’s wearing an ornate robe, with a strange medallion hanging around his neck. A hostile, pitchfork-waving crowd is milling about on the beach, waiting for them to drown. He has no idea what’s going on — he doesn’t remember the Changes. His sister, however, remembers everything — and fills him in. One effect of the Changes was to impart certain mild magical powers to a few people; Geoffrey was able to control the local weather — so he became a successful weathermonger. At the same time, he kept tinkering with the engine of his family’s boat… but was finally discovered doing so, which led to his current predicament.

Geoffrey is able to summon up a fog, then escape with Sally, his sister, to their boat – and motor across the Channel to France. Once they arrive there, they discover that the Changes have proven disastrous for France and other countries, which have had to deal with a mass exodus of the unaffected from England, not to mention all the bad weather which weathermongers like Geoffrey had been shunting away from England for the past few years. So yes, actually, there’s also a climate-change subtext here: continental Europe’s coasts are flooding, crops are ruined, it’s an eco-catastrophe.

Although France and other countries have sent operatives into England to figure out what’s happening, either their airplane engines have failed, or they’ve landed successfully but met with disaster (or fallen under the influence of the Changes). Geoffrey and Sally are prevailed upon to return to England, where they’ll rescue a stranded 1909 Rolls Royce Silver Ghost — whose workings are described in loving detail — and drive it towards an atmospheric disturbance emanating from the Welsh coast.

Is this spot the source of the Changes? As they get closer and closer to their destination, not only are they pursued by maddened men on horseback, who want to destroy their car (and presumably the children, too), but they are attacked by animals and even the weather. What powerful force is attempting to stop them?

Their mission is a fact-finding one, but in the event, Geoffrey and Sally manage to end the malign spell under which England has fallen. Hopefully it isn’t giving too much away to reveal that this book — not so much the other two in the trilogy — concerns what’s known as The Matter of Britain.

Dickinson doesn’t give Sally much to do — in fact, she’s a bit of a drip, though she becomes important at the end of the story. Hollywood, we’d need to correct that.

For Geoffrey, who should not be an action-hero type, I like Asa Butterfield — he is amazing in Sex Education, isn’t he?

A series of movies or TV episodes whose underlying theme was Brexit’s unhealthy, un-British xenophobia and its underlying racism, and pointing a finger at the populists who take advantage of such situations for personal political gain, while making unlikely heroes out of ordinary British children who try to do the right thing, no matter how crazily their elders may behave, would be riveting.

PS: It would be an interesting, telling twist if the Changes were shown to have affected Northern Ireland (seen as an inseparable part of the UK), but not Ireland.

The Weathermonger was dramatized for television in 1975 by the BBC — with some elements from the other two books mixed in; John Prowse directed. (There’s a valuable website — including an interview with Dickinson — dedicated to the BBC adaptation, here.) Although remembered with fondness by English viewers of a certain age, it’s a “patchy” effort — to quote Dickinson.

Hollywood, and the British production companies that co-produce films with US studios, European financing, TV channels, and state funding — let’s make this happen! Get in touch with Dickinson’s estate here.

LISTEN, HOLLYWOOD: Michael Innes’s FROM LONDON FAR | P.G. Wodehouse’s LEAVE IT TO PSMITH | Peter Dickinson’s CHANGES TRILOGY | Robert Heinlein’s GLORY ROAD | Poul Anderson’s THE HIGH CRUSADE | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s TARZAN AND THE FOREIGN LEGION | G.K. Chesterton’s THE NAPOLEON OF NOTTING HILL | Michael Innes’s THE JOURNEYING BOY | Alfred Jarry’s EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN | André Gide’s THE VATICAN CAVES [LAFCADIO’S ADVENTURES].

Also see Josh Glenn’s SHOCKING BLOCKING series: It Happened One Night (1934) | The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) | The Guv’nor (1935) | The 39 Steps (1935) | Young and Innocent (1937) | The Lady Vanishes (1938) | Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) | The Big Sleep (1939) | The Little Princess (1939) | Gone With the Wind (1939) | His Girl Friday (1940) | The Diary of a Chambermaid (1946) | The Asphalt Jungle (1950) | The African Queen (1951) | A Bucket of Blood (1959) | Beach Party (1963) | For Those Who Think Young (1964) | Thunderball (1965) | Clambake (1967) | Bonnie and Clyde (1967) | Madigan (1968) | Wild in the Streets (1968) | Barbarella (1968) | Harold and Maude (1971) | The Mack (1973) | The Long Goodbye (1973) | Les Valseuses (1974) | Eraserhead (1976) | The Bad News Bears (1976) | Breaking Away (1979) | Rock’n’Roll High School (1979) | Escape from Alcatraz (1979) | Apocalypse Now (1979) | Caddyshack (1980) | Stripes (1981) | Blade Runner (1982) | Tender Mercies (1983) | Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life (1983) | Repo Man (1984) | Buckaroo Banzai (1984) | Raising Arizona (1987) | RoboCop (1987) | Goodfellas (1990) | Candyman (1992) | Dazed and Confused (1993) | Pulp Fiction (1994) | The Fifth Element (1997) | Nacho Libre (2006) | District 9 (2009).

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.